Sign In to Your Account

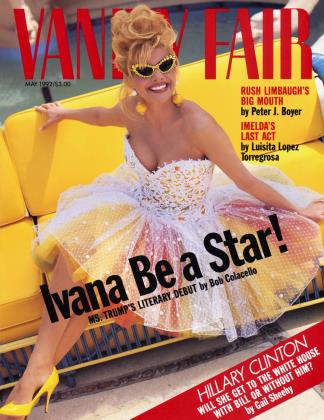

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA New Jay Dawning

What do you do after eight years of being fêted in the fast lane (and kicked around by the critics) for the phenomenal success of one novel that marks you as everything that was right and wrong with the New York eighties Zeitgeist? If you're Jay Mclnerney, you head for a new life with a new wife and put the past into a new novel, Brightness Falls—which, as MICHAEL SHNAYERSON reports, may be his best work yet

MICHAEL SHNAYERSON

Jay Mclnerney, the most celebrated writer under forty in America and the most resented, gives his horse a kick and heads off into the woods at a gallop. We are far from any New York nightclub here. We are deep in the forested hills that circle Nashville, smack-dab in the middle of the New Jay Mclnerney Life. Later, perhaps, we'll do some quail hunting, then sit around the fire at home

while Mildred cooks up some fried chicken and turnip greens. For all this, we can thank the blonde at Mclnerney's side, the beautiful and very spunky Helen Bransford, whose world this is and who, to the dazzlement of her friends and his, married Mclnerney, thirty-seven, six years her junior, after a whirlwind courtship of barely a month. For Mclnerney, who still gets lost driving to get the milk, this is a new life all right, and to cap it off he has a fiercely ambitious new novel, a sort of Bonfire of the Vanities with heart: Brightness Falls (Knopf).

even reckless, Mclnemey has often seemed to court drama, not only in his work but

There's a bit of wry wordplay, of course, in the title. Eight years later, Mclnemey is still the one who wrote that book, Bright Lights, Big City, the slim, phenomenally successful comingof-age-in-New-York novel that seemed to freeze-frame the Zeitgeist in that moment after disco and before the spread of AIDS, when cocaine was nose candy and the hardest life choice was Area or Heartbreak. Young, handsome, and ready to ride, Mclnemey overnight became the literary prince of the party— any party—flanked by his long-locked knights, editors Gary Fisketjon and

Morgan Entrekin, with models and hangers-on in tow, appearing everywhere in person and in print. Though the clubs were downtown, there was something terribly prep-school about it all—here was the cool group you'd never felt a part of, haunting you again— which soon resulted in a backlash of envy. When Mclnemey's next two novels came in equally slim but slight, the same literati who'd raised him up took great delight in tearing him down: the old one-two of American letters, its crudest blows reserved for those who don black-tie instead of tweed and make the grave mistake of basking in their fame. "I can understand how people got sick and tired of all this," Mclnemey says now. "I got way too much attention."

But if there's a nod to that public slide, Brightness Falls is no admission of defeat. At more than four hundred pages, with dozens of characters, it leaps from the Salinger-like single voice of Bright Lights to a bold panorama that tries to record a whole city—New York —in the giddy, nihilistic months before the stock-market crash of 1987. Central to it is a young book editor at a major publishing house who clashes with his boss and finds himself pursuing a bizarre but timely course: a leveraged buyout of his company. Fast-paced and fun, but underscored by a brooding awareness of life's mounting losses, the novel has a make-it-or-break-it, shootthe-moon feel to it: Take this, querulous critics!

The surprise is that the early word is good, even from those who've come to roll their eyes at the mention of Mclnerney's name. ''I think the book is incredibly good, even profound," says critic James Atlas, who plowed through it in a single day. ''He's captured the spirit of New York in the eighties, and the characters, though comic, are portrayed with real generosity."

The characters have certainly helped stir the buzz, for most are drawn from real-life counterparts. Russell, the novel's shaggy-haired editor, is not unlike Fisketjon, Mclnemey's best friend since college and editor of his four novels. Russell works, as Fisketjon once did, for an editor not unlike Jason Epstein, at a publishing house not unlike Random House. One of Russell's colleagues is a black editor not unlike Pantheon's Erroll McDonald (who formerly worked at Random with Fisketjon). One of his authors is a self-obsessed intellectual not unlike Harold Brodkey. Another writer is the longtime best friend who had a dazzling fictional debut and has been slipping since then into drugs and selfdoubt. The writer, of course, is not unlike Jay Mclnemey.

Publishing insiders seem to be deriving deep, if somewhat inane, satisfaction from guessing who's who. For reallife counterparts, the fun is in denying their own portraits and then agreeing that others' are probably true. ''I never once thought as I was reading the book, Gosh, he's using my character as a foundation," says Fisketjon solemnly. ''I think a lot of people would probably suggest another guy with long blond hair as the main character." Entrekin denies that, but happily suggests there's a lot of McDonald in Washington Lee, the black editor who does as little work as he can get away with and relies for job security on the liberal guilt of his white superiors. Which, of course, McDonald denies. ''Hey," he says, ever cool, "if I were uptight about that I would have fought Jay on it. But I wasn't. Because this character is clearly, at least from what I know about myself, a fictional creation. I know people are going to read this book and think I am Washington Lee. But I know I am not that guy. That guy is dangerous!"

As for Mclnemey, he says he is not the novel's troubled young writer doing hard drugs on his sad way down. "That would be incredibly wrong," he says in real consternation. But other characters, he admits in a reflective moment by the fire, are indeed drawn from life. ''I don't want to be an asshole and say, 'Oh no, Erroll's not in the book,' and 'No, I never even thought of Brodkey.' But none of these people is in the book 'as is. '. . . What I wanted this book to be about is marriage, friendship, work, love, and the near impossibility of balancing those things in our lives. Ultimately, the only justification for any of this is: Is it good fiction? Are people who don't know any of the real-life models going to enjoy the characters in this book? If this book is only of interest to insiders in the New York media and social worlds, then I have failed utterly and I deserve to sink into miserable obscurity."

The hope, of course, is that Brightness Falls will have as broad an appeal as that other outsize fictional tribute to New York in the eighties—and then some. Like most readers, Mclnemey admired the dazzling prose and merciless satire of The Bonfire of the Vanities, but felt its characters were caricatures. "I may regret saying it, but what was going through my head when I sat down to write this novel was: What if Bonfire of the Vanities had real people in it?" At about that time, Tom Wolfe published his biting essay in Harper's on the failure, as he saw it, of contemporary American novelists to write the social fiction that summed up their times—perhaps, suggested Wolfe with palpable disdain, because they were too solipsistic and lazy to do the reporting. ''I must say I got a little jolt when I read that," says Mclnemey, who had already begun quizzing investment bankers on the details of takeovers. ''I said, Well, we'll just see if anyone's doing this besides you, Tom."

Mclnemey is quick to tick off other, more literary influences: behind the public image of dissoluteness is in fact a thoughtful student of his craft, well-read and well-spoken. ''I grew up most directly under the minimalist influence: Raymond Carver, Ann Beattie, Richard Ford," he says. ''Which in turn had been a reaction against the metafiction of the seventies: the Barth-Coover-Hawkes-Pynchon conspiracy. Minimalism influenced me, but I became tired of it, and I guess if I had any conscious ambition in this book it was to try to wed the psychologically acute domestic fiction of minimalism with the social novels of the authors I've been reading in recent years: Balzac and Dickens, Trollope and Thackeray."

Brightness Falls is Mclnemey's second attempt to strike that balance with a big book about New York; a first manuscript reached 250 pages in 1986 before its author pushed it aside in disgust. Two years later, at the lowest and most bewildering point in his life, he started all over again.

Ironically, that point came at the apogee of his literary celebrity, in the fall of 1988. Michael J. Fox had just played the Mclnemey character in the screen version of Bright Lights, after hanging out with the author for weeks to ape his every mannerism. A modest success at best, the film had nevertheless made Mclnemey (Continued on page 190) (Continued from page 154) a star in his own right, which had led to more glittering invitations, more drinking, and more drugs. Riding that wave had come Story of My Life, Mclnerney's next monologue novel—to a crashing reception. Though his portrait of a twenty-year-old New York party girl remains almost eerily convincing, the exercise struck critics as trivial and irritating. Mclnerney felt burnedout and beaten-up, and not at all sure that he could write a book again. But he also felt that only writing could save him. One day that winter, he arrived at a cabin on a hill in Dorset, Vermont. Two months later, he had his first 150 pages.

Mclnerney has often written in bursts like that, eight or ten hours a day, until the book is done: Bright Lights came out of a summer, Story of My Life from three weeks at Yaddo. But Brightness Falls was too big a fish to be reeled in that way. Nor was the work made any easier by the fact that its creator, unlike many of his literary heroes, has never been one for outlines; he tends to write short stories that grow into parts of the plot here and there, and to fill in what's between. It's a choice he justifies with a metaphor from E. L. Doctorow: Writing a novel is like driving a car across country at night; though you can see only as far as your headlights, they can get you all the way there. But there's a lot of anguish in that, as Mclnerney found over three years and four drafts. "Many mornings I woke up and said, This is absolute shit, I don't know what I'm doing, it was a mistake, let this cup pass from me," Mclnerney says now. "I was three hundred pages and a year and a half into something, and I didn't even know what it was."

The drama in those words is pure McInemey. For which, suggests one longtime friend, you can blame the Irish blood: impetuous, even reckless, Mclnerney has often seemed to court drama, not only in his work but in his life, relishing the thrill of spontaneity, and yet also aware that the more tumultuous the consequences, the better fiction they may become. The irony is that at this latest turn he's done his job too well: nothing in the book he finally finished can match the drama of his new, real-life romance.

"T never believed that thing about X friends falling in love," says Helen Bransford sheepishly. She sits curled in a chair in her jewelry workshop, silver bracelets and earrings everywhere. Besides, she says, "we always had this age difference. And Jay always had a girlfriend, and I was always dating someone. And Jay was coming into this great wave of attention and fame."

The house that Bransford now shares with her husband lies on a leafy suburban road. Though not large, it feels regal inside, all soft white sofas and pastelsponged walls. In one bedroom stands an imposing mahogany-posted family bed; beside it is a wooden easel displaying family portraits. The jewelry workshop lies off the living room. Almost all of Bransford's business is word-of-mouth, to the New York publishing set and now, more than before, to Nashville's countryand-western elite.

Bransford's family, in fact, is one of Nashville's oldest. Her great-grandfather was secretary of state under President Taft and lived in the city's stateliest mansion, Belle Meade, now a public showcase; her mother was bom there, too, and retained enough old-world gentility to insist that Helen, as a young lady, wear white gloves whenever she traveled. To Morgan Entrekin, another Nashville native, the Bransfords were always the real thing, the sort of southern family whose lineage is known for miles around, down to the last half-cousin.

It was in 1984 that Entrekin invited Bransford to a dinner he was throwing at Elaine's in honor of Bright Lights. "It was the first time at Elaine's for me," Mclnerney recalls, "and there was Gary [Fisketjon], and Morgan, and I think P. J. O'Rourke, and my wife, Merry, maybe a couple of others. After about half an hour Helen walked in, and I thought, Here is the most drop-dead gorgeous girl, something's happening here, this is my life now. I was totally swept away by her; I thought she was a symbol of everything I'd been trying to come back to in New York. That was the moment, when I met Helen, that the lights in New York came on for me."

By then, Bransford had managed to shed the white gloves. A short, unhappy marriage had induced her to move to London, where she fell in love with Isaac Tigrett, a founder of the Hard Rock Cafe, and worked as a waitress and cashier at the original club for some time, a beautiful blonde with nubs for nails thanks to goldsmithery school. Drifting to New York, she became an assistant to P.R. man Bobby Zarem, and lived with Warren Hoge, then of the New York Post. She served briefly as an editorial publicist for New Times; one sweltering summer Sunday, editor Peter Kaplan happened by the un-air-conditioned offices to find Bransford on the phone, hard at work—stark naked, with phone numbers scribbled on her arms in red ink.

"Someone once said to me, 'When you're going to hold up a bank, Helen's the one you want to drive the getaway car,' " says Suzanne Goodson, a fellow southerner and one of Helen's closest friends, who met her as she was beginning to make her name as a jewelry designer. "She does exactly what she wants to do, and always has; she's totally uninhibited. "

In recent years, Bransford dated a number of socially visible men, including author William Goldman and CAA agent Ron Meyer. But even Suzanne Goodson would not have predicted, last November, that Helen Bransford would marry again—certainly not a younger man. "I was.. .so stunned."

For seven years, Mclnerney and Bransford had served as each other's stand-in at black-tie events. ''I always found myself saying to people, 'No, you're wrong about him,' " says Bransford. "I felt he'd gotten really overexposed through his own innocence, to his own detriment." Every Christmas, Mclnerney would buy jewelry from her for his agent and close friend, Amanda Urban, and various girlfriends. ''Well, Jay," Helen would greet him cheerily, "I hope you've been promiscuous this year."

Then, last October, Mclnerney separated from .former model Marla Hanson, after a high-profile romance of more than four years. The understanding was that both would take some time to assess the relationship, then decide in late December what to do. One evening Mclnerney joined Bransford for a movie with Suzanne Goodson and Jerry Goldsmith, of Rothschild, Inc. At Raoul's afterward for dinner, Goodson began to notice a certain electricity in the air. ''I could see the way the evening was turning. Toward the end of the meal I said something about how Helen and I had been classmates—which was a dig, of course, because Helen's six years younger than I am. She smiled, and glinted, and then calmly poured a glass of water down my chest. That's when I knew it was time to go. 'Come on, Jerry,' I said, and kicked him. But as I leaned over to kiss Helen good-bye, I dumped my glass of water over her."

Helen flew back to Nashville the next day—not only to feed her six cats and catch up on business but to check in with her live-in lover, a local doctor. Though she hates to fly, she returned twice to New York in early December. ''I guess we were sort of hoping we'd get sick of each other," says Mclnerney. Bransford was skeptical herself. ''In every romance I'd ever had, I'd hoped to have a situation that was black-and-white with no reservations, with real convictions. I'd never had that, so I thought, Hell, grown-up life means there're always shades of gray. But, in fact, that's what this was."

One day in the midst of this, Hanson, who still had keys to Mclnemey's Village apartment, went over while he was out and found a love letter to Helen. Angry and hurt, she confronted him, which led Helen, in turn, to tell her doctor friend over breakfast one morning in Nashville that she was in love. "So then," says McInemey, "we were out in the open."

By Christmas, Mclnerney had proposed—on bended knee in a crowded Nashville restaurant. "Two people more allergic to marriage you would have been hard-pressed to find," he says. "But suddenly it seemed like a romantic concept." Jim Signorelli, a Saturday Night Live producer who's been one of the gang since Mclnemey's early days in New York, describes his friend as "romantic beyond all hope." Beyond all reason seemed more like it that Christmas week: the plan the lovers hit upon was to get married in secret, then keep the secret for the rest of their lives. City Hall seemed right, but they needed a witness. That Thursday, they called reporter Marie Brenner, a longtime mutual friend, and asked her to serve. Friday at noon, Brenner showed up with rice, a bouquet, a camera, and her daughter, Casey.

The secret held—for about five days. By then Liz Smith had heard the news and warned she'd have to run it; reluctantly, the newlyweds began calling family and friends before the item appeared. One of Mclnemey's calls was to his father, to announce that a woman his father hadn't met was his brand-new daughter-in-law.

Another call was to Marla.

RING ONCE, reads a sign by the buzzer. THIS ELEVATOR IS VERY SLOW.

After many minutes and more than one ring, the door slides open and Marla Hanson, in scruffy clothes and no makeup, flashes a smile of welcome. Her scars are fainter than they once were, but still visible enough to shock on first sight—jagged lines of urban violence that stun strangers into awkward silence.

We are in Tribeca, in an old building given over to video production, where Hanson has rented an editing room to finish the thirty-minute short that will enable her to graduate this summer from N.Y.U. film school. The film is entitled Love in Transit. "It's about lust from a woman's point of view," says Hanson with a wholesome smile. In her voice, and in her manner, she is still unmistakably a nice, sensible, small-town Texas girl. Considering how abruptly her lover of more than four years up and married someone else, she is also surprisingly gracious—though candid.

In a sense, she says, the end was no surprise; there had been conflicts from the moment Hanson learned, two months into the relationship, in the summer of 1987, that Mclnerney was not divorced, but merely separated, from his second wife, Merry. "By the time I found out," she says ruefully, "I was madly in love." Not only was Mclnerney black-Irish handsome, famous, and charming, he seemed to offer the ravaged twenty-four-year-old a new and desperately needed life after the razor-slashing street attack that had scarred her face and psyche, and destroyed her hopes of a modeling career. Indeed, the whole city had been buoyed by the romance; it seemed like a fairy tale.

By the spring of 1988, Mclnemey's marriage had erupted into a conflict of a different, more painful sort, when Merry, despondent in Michigan over her husband's romance with Hanson, attempted suicide and was committed briefly to an institution. What she needed, he felt, was the best place money could buy. The best place, friends counseled, was Connecticut's Silver Hill Hospital.

Merry remained at Silver Hill for nine months. Because her distress was emotional, not physical, insurance paid for only two weeks of that stay. Mclnerney paid for the rest. The bill ran to hundreds of thousands of dollars—a good part of the money he had made from his three novels as well as from his Bright Lights screenplay. For Mclnerney, always beguiled by the work and life of F. Scott Fitzgerald, this was a lot more Scott and Zelda than he'd ever wanted. For Hanson, left alone every weekend as Mclnerney went to visit Merry, it wasn't much fun, either.

In early 1989, Merry went back to Michigan, where she remains, leading a healthier life. As part of the divorce settlement, Mclnerney agreed to support her for a set number of years, a period that has not yet expired.

And then there were the endless temptations. "People were always wanting to sweep Jay away," Hanson explains, "and he was the sort of guy who gets swept up by everything he does—writing or partying. You'd get, not jealous, but tired after a while, tired of competing. Not only with the girls but the buddies. If I heard the names Morgan, Gary, or Jim..." Hanson rolls her eyes. "It was worse than hearing girls' names. 'Morgan—oh no!' Because I knew that meant he'd be home at four in the morning."

Soon after the trial of her attackers, Hanson enrolled at N.Y.U. After days spent in classrooms—a trial in itself, enduring the morbid curiosity of fellow students—she would come back with homework to do. Mclnerney, having spent the day writing, would want to go out, and, especially when the invitations were glamorous, Hanson felt tom. Even when she could balance both worlds, she didn't feel good. Mclnerney was older, and he had a career. He got paid to write film treatments; Hanson paid to write them at school. She adored Mclnerney's friends, but never forgot they were his; when she tried to introduce him to friends she was making, she felt his impatience was painfully clear.

In an effort to both deal with her lingering trauma and establish a life of her own, Hanson went on the lecture circuit, speaking to other victims of violent crimes. At first the speech-giving brought her satisfaction, as well as some money. Eventually she felt trapped by her role, not only reliving her pain but being defined by it— being, as one introducer put it, a "celebrity victim." Gradually, she began to feel more confidence in her film work, but Mclnerney seemed oblivious to that.

"The relationship was always tied into what had happened [the attack], because it started right after that. I always felt Jay saw me only in that light. Because he was around me every day, he didn't see the progress I was making. I would always be the way he met me in his mind. And when I started to make this film, he said, 'You're actually making a film?' I thought, What does he think I've been doing for four years in school?" Hanson shakes her head. "I adore Jay, and I loved being with him, and I thought he was a big influence on my life, but I always thought it wouldn't last. I needed to be with people who were on the same level as me, for my own self-assurance."

Last summer, Mclnerney tried to repair the damage by whisking Hanson off for a sybaritic summer in Italy, the Hamptons, the British Virgin Islands. It was a noble effort, but one hampered somewhat by the fact that he spent part of every day revising Brightness Falls, while she had little to do but read more of the serious novels Mclnerney, in Pygmalion fashion, was always passing her way. That October, when he spent a weekend on Long Island without her, Hanson assumed the worst and made the decision to leave. Despite a flurry of phone calls from the gang urging her to reconsider, she moved out of his apartment into a small sublet. In a way, the AWOL weekend was just an excuse. "I felt this was the year I had to really get over [the attack] and go on to something else. . . . And I think in a way Jay was a part of that."

At the same time, there was the real possibility the two might get back together. "I mean, we'd been talking about children and marriage." Hence the wait-andsee period, during which Hanson would finish her final fall term. "I took that very seriously," she says. "And it was an important time for me, although it was very painful. I just couldn't get out of bed— there I was where I'd been five years ago, lying in bed, watching the sun go up and go down."

More painful was the inadvertent discovery of Mclnerney's romance with Bransford. Hanson says she went through three torturous months, but has come to feel philosophical about it. "They're much more similar than Jay and I are. And Helen's got a big life, all that blueblood, high-society stuff.. . " But the notion that they might have kept their nuptials a secret provokes a wry smile. "You go to New York, to the justice of the peace, and invite Marie Brenner. . .you think no one is going to find out?" And the pain—of having, as she puts it, to clean up the mess—still obviously bothers her.

"You can't just bring someone new into your family and expect them to care about her and take someone away that they've been caring about for four years," she says. "And people have children who see you as a group, and you have to contend with that. 'Where's Marla?' They don't understand that. And you have a house, with all your stuff together. And there you are, cleaning up somebody else's clothes when they're living with someone else already. Packing his clothes boxes—he'd rented the apartment to someone else, and they're moving in, but there's still shoes on the floor and trash in the trash cans, dirty sheets on the bed. And you're standing there thinking, It's not really my job to do this, because it's not my house. But you can't let the people move into it this way." It takes a minute to realize why that speech sounds so familiar: it's so close to the second-person voice of Bright Lights.

Hanson says she hopes she and Mclnerney will be friends, but she isn't entirely sure he'll want to be. "In a strange way," she says softly, "I ended up on the other side, exactly where Merry was. He was reacting to me like he had reacted to Merry. And it didn't feel very good."

Though the Village apartment is gone, Mclnerney remains a part-time New Yorker, having moved his belongings into an apartment Bransford recently acquired on the Upper East Side. His friends see the change of address as symbolic, and Mclnerney, with some pride, agrees: the downtown kid has grown up. How long he and Helen will stick to their plan of keeping Nashville as home base is less clear. Already, Mclnerney is logging heavy frequent-flier miles, heading north at the drop of a dinner invitation. One night while he's in town we meet at the restaurant of his choice: not Odeon or Indochine, but "21."

It is, of course, the perfect choice. A throwback—almost a time machine—to the Jazz Age days of F. Scott Fitzgerald, when a writer could be the toast of the town, and Fifty-second was Swing Street. Mclnerney loves the history; he loves the clubbishness and snobbery too. A scene in Brightness Falls takes place in the restaurant's cavelike first-floor dining room, with careful reference to the tradition of honoring regulars by hanging appropriate toys from the ceiling: a toy boat for a shipping magnate, and so forth. When I suggest, over the din, that we take one of the tables in the quieter far comer, McInemey and the maitre d' flash me the sort of pitying looks one reserves for the mentally enfeebled. The comer, Mclnerney explains, is Siberia; we sit instead at a little round table by the front door, the better to see and be seen.

"This used to be the refuge of people who grew up on Park Avenue, the place fathers always took sons when they came home from college, to have man-to-man talks," Mclnerney explains. The irony, as he freely admits, is that he wasn't one of them. In fact, he grew up in small towns all over New England, Canada, and Europe, the eldest of three sons of a papercompany executive who got transferred almost every year. As the perennial new kid—eighteen schools before college— Mclnerney sought out each next local library as a refuge, and nurtured outlandish dreams of being a writer too, a rich and famous writer in New York who would eat at "21." "My father always had business in New York, and he'd come back and tell me about this place that had hamburgers that cost twelve dollars," Mclnerney exclaims. "I couldn't believe it!"

The hamburgers cost $24.95 now, most of the entrees a good deal more than that. As for the wines, they seem to be priced in pesos. Unfazed, Mclnerney engages in earnest talk with the sommelier and selects a 1989 Puligny-Montrachet Les Perrieres. In his years of success, he has become a raving oenophile, much to the exasperation of his friends. The wine talk seems terribly authoritative, but there is something a bit de trop about it—as, for that matter, there is about the all-Armani wardrobe. On some level, Mclnerney is still the wide-eyed boy from the provinces, marveling at big-city glamour and plunging into it with innocent gusto—what George Plimpton calls "that wonderful exuberance and inability to go to bed."

For a while at Williams College, Mclnemey remained an outsider among preppier peers. But by junior year, when Gary Fisketjon transferred from the University of San Francisco, Mclnemey had established himself as the campus poet. "A number of people on the literary magazine told us we'd really like each other. Of course, as a result we hated each other," Mclnemey recalls. The tension intensified when both took an interest in the same coed. One night in the campus pub, Fisketjon breezed coolly by Mclnemey's table and flicked a lit cigarette into his pitcher of beer. "I think I got up to hit him, and someone stopped me, and then somehow by the end of the evening we were talking furiously about John Berryman. And then we were best friends."

Fisketjon, who'd grown up on a mink farm in Oregon, had no more acquaintance than his new friend with the New York publishing world, and yet both shared the same quixotic dream of conquering it someday. They read literary quarterlies and had late-night debates about new favorites, Raymond Carver among them. When Mclnemey's parents

gave him a car for graduation, he and Fisketjon set off on a sort of faux-Kerouac cross-country journey. In Nashville, as it happened, they got conned by a guy who took their money to show them the sights; in Oxford, Mississippi, they slept in Faulkner's yard; in New Orleans, after a Willie Nelson concert, they saw a man killed in the parking lot. Which was why they decided to drive west through the night, and why, on too many stimulants and too little sleep, they got into the one real fight of their friendship. "We started arguing about Norman Mailer—I was pro, and Gary was con—and we started screaming at each other. We didn't come to blows, but it was pretty bad. We ended up pulling over to a rest stop and sleeping in the bushes."

As if on cue, Norman and Norris Mailer walk into "21" with another couple and take a table nearby. Warm greetings are exchanged; Mailer has been a friend and supporter since Bright Lights, and seems to have taken an old fighter's pleasure in watching the kid put up his gloves in the ring of literary celebrity. "My feeling is that young writers really have two choices," he remarks some days later. "One is the tower and the other is the media field. Jay's chosen the latter, which can be tougher, and I like that quality in

him: he's saying, 'One reason to write is to be a public figure and have people feel a ripple of excitement when I come into the room, and I want that.' I think that's good. After all, novelists may soon become as recherche as poets—if there isn't some sense of excitement in being a writer, how many people will do it?"

By now we are on to a bottle of 1982 Pichon Lalande—and the Mclnemey story is assuming the scale of an epic. Like most, writers, Mclnemey loves talking about himself, and, indeed, one learns over time that it's a struggle to get him to focus on anything else. But he does it with such childlike delight that his friends always seem to forgive him. And as he does, what comes clear is that at every stage he's asked himself: What would a writer do now? What would Hemingway do? Or Fitzgerald?

Which is why he thought, as his trip sputtered to an end in San Francisco, "O.K., I've done the Kerouac thing, now I'll do the Hemingway thing." While Fisketjon went through the Radcliffe Publishing Course (where he met Entrekin) and headed down to New York to take a firstrung job in publishing, Mclnemey drifted back East with the notion of getting a newspaper job. But a short stint on a New Jersey weekly proved disastrous— Mclnerney spent hours fashioning his leads but got his facts all wrong. When an old professor suggested he apply for a Princeton fellowship to write in Japan, Mclnerney leapt at the chance.

Japan was Mclnemey's Paris: the expatriate period punched on his literary ticket, and the basis for his second novel, Ransom. And as with all expatriates, there came a time when it seemed he must leave or not go back at all. With his imagination fired by almost daily letters from Fisketjon that conjured wondrous images of life in New York, the choice wasn't difficult to make. Even more eager to leave was Mclnerney's half-Japanese girlfriend, Linda Rossiter, a dark beauty who hoped to pursue an American modeling career. Before returning, Mclnerney married her. If he had thought the institution would bring him stability, he was mistaken. "Off we went, me to be the writer, she to be the model. Seemed like good work if we could get it." Mclnerney laughs. "Well, she got it, but I didn't!"

To pay the rent on his small downtown apartment Mclnerney put in time as a fact checker at The New Yorker, the memorable period that so enlivened Bright Lights. After he was fired—a precedent at the magazine, he says with some pride'—McInemey turned for help to Fisketjon, who found him a job as a freelance reader for Random House. The payoff for a typically dreary day was, at least, an evening of downtown clubs with Fisketjon and sometimes Entrekin, sluiced by drinking and drugs. Perhaps because his friends had real jobs they cared about, Mclnerney was the one who seemed to have the most trouble keeping his appetites in check. When Rossiter flew to Milan for a fashion show and simply failed to return, his life seemed dangerously adrift. Once again, Fisketjon bailed him out—this time not with a job but with a savior—in a typical turn of Mclnerney drama.

"We'd been up late drinking the night before, and I was trying to write when Gary called to ask if I wanted to meet Ray Carver," Mclnerney recalls. "I thought he was kidding, and hung up on him. He called back and said, 'No, really, Carver's coming over to your house; he's here in New York with nothing to do for the afternoon, so I told him you'd show him around.' Suddenly the buzzer rings, and there's this big bear of a man who was one of my great heroes." The two talked for six hours, joined eventually by Fisketjon and Richard Ford, before heading uptown for Carver's reading at Columbia. Not long afterward, Mclnerney got a letter from Carver suggesting—not very gently—that if he wanted to get serious about writing he head up to Syracuse, far from the city's temptations, and become one of Carver's students. "It was lucky that I met him when I did," McInemey admits. "Not only because of where my life was, but because of where his life was. He was a guy just recovering from being an alcoholic, not yet a great American writer. Not long after, he had to close the door a bit."

There was no romantic literary model for the three years Mclnerney spent at graduate school in Syracuse, just a lot of hard work learning his craft. During that time, his mother died of cancer; not long after, he met Merry and began to work on Ransom. Not until the spring of 1983 did he knock off the short story that became the first chapter of Bright Lights, and then go on, in a feverish three-month burst of energy, to finish it. Three more months passed from the time he sent it to Fisketjon until the day, just before Christmas, when Fisketjon called to say that Random House would publish the book, and that, what was more, his boss, Jason Epstein, had suggested the standard first-novel advance of $5,000 be upped to $7,500. For the Mclnerneys, living at this point on a $6,500-a-year grant, that seemed an almost unbelievable sum of money. "That," says Mclnerney over the din of diners at "21," "was one of the happiest moments."

When the check comes at last, after two glasses of 1963 Taylor Port, it's so high I can only marvel: $448 for two people, before tip.

What a long, strange trip it's been.

One of the more striking ways in which Brightness Falls is different from Bright Lights is in the station of its characters. The clubgoers of Bright Lights are outside the kingdom—kids working at entry-level jobs. The somewhat older characters of Brightness Falls have made it in to grapple with the perils of success. Since Bright Lights, and to a considerable degree because of Bright Lights, their real-life counterparts have made the same trip.

Fisketjon, a rising young editor before Bright Lights, nevertheless has had a far more dramatic eight years because of the book than he might have without it— tapped first as editorial director of Atlantic Monthly Press, then, after a somewhat tumultuous tenure not helped by the critical failure of Mclnemey's Story of My Life, zigzagging to Knopf as a senior editor. Entrekin's debt to Bright Lights is less direct, but not that much so: the book's success paved the way for Bret Easton Ellis's Less Than Zero, which Entrekin published the next year. From Simon & Schuster he followed Fisketjon to A.M.P., forming his own imprint and remaining after his friend's departure. Last September, in a surprise move, he managed to raise the money to buy out the company. "At the time I was thinking of buying it, I called Jay and said, 'What do you think?' " Entrekin recalls with a grin. "He said, 'Damn it, everybody's going to think Brightness Falls is about that!' "

Mclnerney's own arc is harder to judge. Bright Lights remains so clouded by its subsequent hype that critics seem to remember it as some crassly commercial ploy, not a serious coming-of-age novel with modest expectations written by an unsophisticated out-of-towner who had to go with somebody cool to get into the Mudd Club, as Mclnerney puts it. For all the critics who panned his second and third novels, there are others who adored them— particularly in Europe, where Mclnerney is seen as issuing bulletins from the American pop-culture front. ("The farther you get from New York," declares agent Amanda Urban, "the higher the critical esteem in which he's held. ") In the view of his peers, too, Mclnerney has done well; writers as diverse as Mona Simpson and Robert Stone treat him with serious respect (though Stone admits to marveling at the chasm of time between his own, politically charged literary youth in jeans and long hair and Mclnemey's in black-tie—a throwback indeed). And then there is his strongest literary supporter, Julian Barnes.

Barnes, with whom Mclnerney engages in a teasing one-upmanship by fax almost daily, comparing foreign-rights sales and fine wines imbibed the night before, calls Mclnerney his best American friend. But he adds, "I start from the position that he's a very serious writer. I thought Bright Lights was good—the second-person narrative and other elements were intriguing—but I couldn't tell. It was with Ransom that I could see he was a real writer—it showed range. Then I thought Story of My Life was his best book so far. It was taut and funny and nasty, with a perfect ear, which is one of the things about Jay. So it seems ironic and ridiculous to me that he's thought to have had a wonderful success with his first book, then a failure or two—to have had a Fitzgerald-like graph—when in fact I look at him and think he's an extremely funny, intelligent man and wonderful company who's getting. better with each book."

Like certain other American writers— Ernest Hemingway and Irwin Shaw, to take two—Mclnerney has not been shy in taking on his critics in print or coming up with his own theories of what ticks diem off. "I think there's a tremendous reverse snobbery that sophisticated New York media people have about the world in which they live," he says. "They think real fiction is about the American workingman, or about burned-out drunks in trailer parks. Real life isn't this life that we live; it's somewhere out there in the rest of America, or in Zimbabwe or somewhere. But this world is at the least no less interesting than, say, Gogol's bureaucrats or Carver's unemployed lumberjacks. To me, New York is the greatest living theater that there is."

Also, for a writer prone to temptation, the most dangerous. And that, more than critical fire, is what has put a wobble in Mclnerney's career arc. For eight years now, strangers have been pressing cocaine on him, literally slipping him foilwrapped grams as they shake his hand— in nightclubs, on book tours and college campuses—just for the kick of partying, if only for a moment, with Mr. Bright Lights. Though he says drugs no longer hold much interest for him, he also says he has no regrets. "Yes, I have used virtually every kind of drug you can think of. And guess what? A lot of it was just plain fucking fun. And that's what some of the A.A. people forget. Hey, it wasn't just an escape; it was like sex. It had a lot to do with sex. It made it easier to sleep with a stranger—and more fun!"

Mclnerney says that, unlike the writer in Brightness Falls, he has never checked himself into a rehab center. He admits to being self-destructive, to having an addictive personality, to being a hedonist. But always, he says, just in the nick of time, he's managed to pull himself away from New York and write his way out of the pit. Even now, though, New York seems to hold the power to thoroughly disrupt him. "Does he realize that living in New York and being in the tabloids is not the greatest thing for a writer?" muses one older writer who's witnessed that power. "Does he know how difficult it is to sustain a career for twenty-five or thirty years? And how the celebrity machinery of this city grinds you down? Because the need to write is emotional, but so is the gratification you get from publicity. And the more you get from public recognition, the less need there is to write. The stuff drips out of the faucet."

So far, Mclnerney seems to think he can still do it all. But, as one friend suggests, part of Helen Bransford's appeal is the refuge Nashville offers from New York, and the steadying influence that one very grown-up southern lady can exert on her younger man. "Jay has sort of had a woman for each period of his life," the friend explains. "Linda was for the expatriate-in-Japan period, Merry was for the intellectually-making-it period, and Marla was for the fame period. So Helen? She's for the new, at-home, takecare-of-Jay, I-work-too-and-I ' m-not-depressed period."

On a warm Saturday night in Nashville, Mclnerney and his not-depressed bride throw their light little dinner for ten: fried chicken, turnip greens, com mash, potatoes with gravy, and fried com bread, all courtesy of Mildred, the Bransford family's longtime cook and overseer. Morgan Entrekin is scheduled to come, but not untypically misses his plane in New York. A young record-company president arrives, along with one of the powers in country-and-westem P.R., and, among others, Jimmy Buffett and his pregnant wife, Jane. It's all clearly emblematic of the new Mclnerney life—a nice southern evening at home, fine wine but no drugs, not even any margaritas. Buffett, in fact, is now something of a health nut, despite the musical tributes to drinking in Caribbean climes that continue to earn him millions on tour every year. Slimmed-down and balding, he wakes up at 6:30 every morning and hurries off to the gym. "But don't tell 'em that!" he says in mock horror. "Tell 'em I'm up drinking and doing drugs till four A.M.!"

Not too long ago, Mclnerney and his friends liked to call themselves the bad boys. But, like Buffett, they're mostly talk now, not much action. Fisketjon has been married, and a father, for years. Erroll McDonald is married, too, and says his greatest high is changing his baby's diapers. Now that Mclnerney is married again, Entrekin, the last prowler, says that he's lonely, but that he's working too harjJ keeping Atlantic Monthly Press afloat to do much dating or carousing.

It all sounds terribly mundane, of course. But, as Mclnerney is discovering in Nashville, there are certain trade-offs for giving up the clubs, and the drugs, and the girls. Like a wonderful wife, and happiness with her. For Mclnerney, voice of his generation, it all suggests something truly radical: growing up is.. .in! □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now