Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

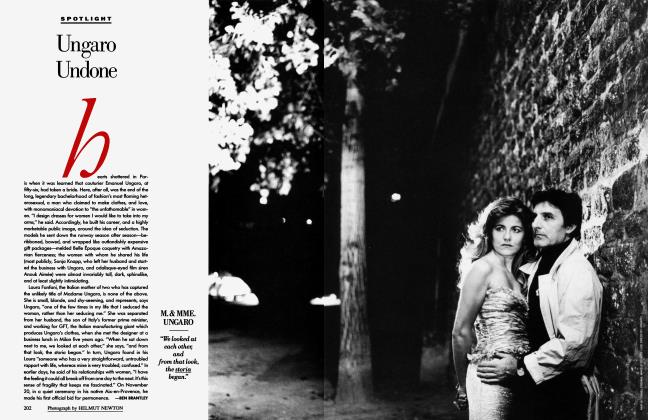

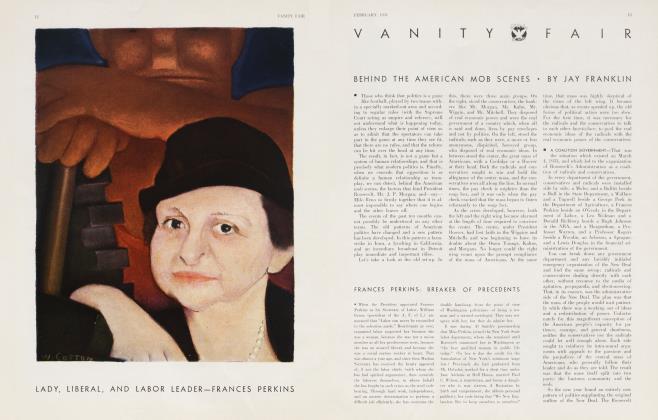

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe roller-coaster life of Carol Matthau—hard-luck waif turned cafe-society debutante turned Hollywood wife (of Walter)— is straight out of a fairy tale. Or maybe a novel. The bewitching muse of William Saroyan, James Agee, Kenneth Tynan, and Truman Capote, who based Holly Golightly on her, she's now writing her own story in her memoirs, Among the Porcupines. BEN BRANTLEY reports

MAY 1992 Ben BrantleyThe roller-coaster life of Carol Matthau—hard-luck waif turned cafe-society debutante turned Hollywood wife (of Walter)— is straight out of a fairy tale. Or maybe a novel. The bewitching muse of William Saroyan, James Agee, Kenneth Tynan, and Truman Capote, who based Holly Golightly on her, she's now writing her own story in her memoirs, Among the Porcupines. BEN BRANTLEY reports

MAY 1992 Ben BrantleyCarol Matthau's voice is small, feathery, and slightly braised-sounding, suggesting a five-year-old with a three-pack-a-day habit. It was, a friend of hers assured me, "the first whispery beautiful voice—much nicer than Jacqueline Kennedy's." During the weeks I was doing research on her, it would resonate breathlessly on my answering machine with such messages as "Please call. . .It's. . .uh. . .well, nothing is important, but if there was such a thing, this would be." The wife of film star Walter Matthau—and a woman known as one of the most outspoken, and surreal-seeming, presences in Hollywood, the capital of surreal—would sound both dazed and hyperalert, like someone who hadn't slept the night before, which was usually the case. This lent a sense of wartime urgency to even our earliest telephone calls, which would spiral into free-associating monologues on everything from mortality ("I don't believe in death, you know") to lost lingerie (''There wasn't a question of alimony [from her first husband, novelist William Saroyan], but I did want my old brassieres back"). A few days before I left New York for Los Angeles, where we were to meet, she concluded the conversation with a perfect, curtain-raising plea.

"We all play roles. Carol chose a good one," James Agee told Artie Shaw.

"You won't make me sound like a fool, will you?" she said. "No, I know you won't. You're going to invent the most beautiful lies for me. You're going to make up the most wonderful person who never existed. And it's going to be a novel."

Actually, Carol Marcus Saroyan Matthau has a right to expect a novel. Before settling into a thirty-two-year marriage with Matthau, she played wife, lover, and confidante to a hallowed assortment of men of letters— Saroyan, James Agee, Kenneth Tynan, and Truman Capote. "We all play roles," the bandleader Artie Shaw remembers being told by Agee. "Carol chose a good one." So good, apparently, that it has been translated into at least a half-dozen works of fiction, each embroidering on the conceit of a dithery child-woman with a mind as sharp and prismatic as cut crystal.

From the time they first divorced (they were married twice), Saroyan couldn't stop writing about her, in a series of bitter domestic novels which characterized her as "something like the Match Girl dressed up and something like Queen Evil herself." Artie Shaw, in one of his early stabs at fiction, presented her, thinly disguised, as a seventeen-year-old debutante on a trip to Hollywood, "this little baby-faced chick with that innocent-looking kisser. . .making the rest of them pros look like a bunch of St. Bernards." And Capote, when he was creating Breakfast at Tiffany's, made a point of spending as much time as possible with the newly divorced Carol Saroyan. "You know I didn't pick you to be Holly Golightly for nothing," she remembers his saying in reference to American literature's most worldly waif. "You are Holly. It's just that you didn't do those rotten things that Holly did."

Friends speak of her life as if drawing from chapters in a novel. "There's a whole group of people, all over the world, whose only connection is our love for Carol," says the actress Maureen Stapleton. "You see them, and the first thing they say is 'How's Carol?' First thing." They quote her one-liners—caustic epigrams delivered with lethal little-girl sweetness—as though she were Dorothy Parker. And they speak of her unvaryingly ethereal style—pastel clothing, cheeks rouged in circles of pink, and the whitest face powder this side of a Kabuki theater—as though analyzing a painting.

(Garbo, after meeting her, described her to a friend as "a delicious little albino.") "Over the years, and I've been her friend for forty of them, people have tried to imitate her," says Lillian Ross, the New Yorker journalist. "But she is inimitable."

The persona took shape early on. The illegitimate daughter of a beautiful sixteen-year-old French-Russian emigre named Rosheen Doree and a father whose name she has never known, Matthau says she spent the ages two through eight in foster homes, before being reclaimed by her mother— who had by then married a wealthy Bendix Aviation executive named Charles Marcus— and introduced into Fifth Avenue splendor. "I think in that wandering through those homes, Carol somehow, somewhere, had to shelter her feelings and her sensitivities," says her younger half-sister, Elinor Pruder. "And in doing so she created this totally magic fantasy, a fairy-tale-like life, like a cocoon. She completely enveloped herself in it, and has fought all her adult life to retain that."

The conductor Leopold Stokowski, who married Matthau's best friend, Gloria Vanderbilt, gave Carol the appropriate nickname of Melisande, after the enigmatic, melancholy young wanderer introduced to a royal court in the Maeterlinck play. More recently, Matthau tells me, when Glenn Close was considering playing Blanche DuBois, the aging, beauty-seeking fantasist of A Streetcar Named Desire, director Karel Reisz told her she should seek out Carol Matthau, because "that is Blanche DuBois."

"That really isn't a great compliment," says Matthau, her voice dropping a register. "It just isn't. How could I be? I'm the one thing Blanche was not—a survivor." That, at sixty-seven, she is one is made clear in her autobiography, Among the Porcupines, which Turtle Bay is bringing out this June. The curious title was inspired by a Schopenhauer parable about a group of porcupines huddling together for warmth on a freezing day while trying to avoid pricking one another with their quills. It is a metaphor for a life spent trying to find a place among the great and difficult, in a world which was never quite as pretty or reassuring as the author longed for it to be.

Among the Porcupines is Matthau's first book since The Secret in the Daisy, an elliptical, wistful fictionalization of her childhood, was published thirty-seven years ago under the name of Carol Grace. In the interim, she made fleeting appearances as an actress onstage and in film (most memorably as a love-wounded gangland mistress in Elaine May's Mikey and Nicky, in 1976), but mostly she focused on what she considers her true raison d'etre—making the life of Walter Matthau, whom she married in 1959, "sing."

The memoirs were born eight years ago, while she was on location in Tunisia and the Seychelles with Walter for Roman Polanski's ill-fated swashbuckling film, Pirates. The heat was crippling, Walter was miserable working for the man he describes as "Hitler's surrogate," and Carol had developed a still-undiagnosed condition which was causing her to lose weight steadily and fall asleep at the dinner table. (It has been tentatively labeled "malabsorption.") "I knew I was dying," she says. "I couldn't hear music. I couldn't see anybody. I was getting cocooned into nothingness. . . .But I could write on a yellow pad—that's the one thing I could do. And I did. I wrote and I wrote and I wrote."

Some of those scribblings would find their way into Among the Porcupines, which she had initially planned as a series of lyric reflections on her years in California. She wrestled endlessly with her editor, Joni Evans, over the book. Matthau says she doesn't believe in autobiography—that you learn more from what a person omits than what she includes. And in her finished work she herself is tellingly scant on her seminal relationship with her beautiful, elusive mother and mute on the subject of her recent estrangement from her two children by Saroyan.

Nevertheless, the book contains enough intimate anecdotes about legendary names—Capote, Agee, Garbo, Rex Harrison and Kay Kendall, Henry Miller, Isak Dinesen, as well as her closest friends, Gloria Vanderbilt and the late Oona Chaplin—to satisfy several varieties of gossip addicts. There are even between-the-sheets confidences, such as Matthau's description of "discovering" oral sex with Bill Saroyan. But they are delivered with the wide-eyed whimsy of a self-styled Alice in Wonderland, though there's the sense that beneath the chipper caprice is an abiding current of melancholy.

Matthau says, in fact, that she is "mostly" in pain. "But, you know, one plays the game. You have to. For other people. Yeah, things haunt you, things you least expect. Maybe just a little girl I saw on a street comer in Paris—just a little girl by herself, not knowing which direction to go in."

There is no hint of somberness in the home Carol Matthau has created in the Pacific Palisades, a tidy, flower-filled suburb off Sunset Boulevard. A rambling pink hacienda-style structure, guarded by pear trees strung with tiny lights, it has interiors which bloom with all forms of roses, artificial and real—on the Colefax & Fowler wall coverings and upholstery, on the rugs, in stenciled paintings on the wooden floors. Urchin dolls, resplendently dressed, and pastoral porcelain figurines abound. It is a thoroughly feminine environment, disrupted only by the presence of an unshaven man with a corrugated face in a baseball cap who is trying to find a place among the bibelots for a plate of chicken salad.

"This is my wife's idea of a comfortable home," says Walter Matthau, the great character actor, impatiently pushing aside a plump sofa cushion. "There's never any place to put anything. All these pillows so you can't sit down. All for show, of course."

We are waiting, of course, for Carol, which will become my custom over the next several days. ("It's my worst fault," she says later. "Please don't be mad. It's just I try so hard to make myself look pretty for you.") Finally a dulcet voice ("Will you ever forgive me?") sounds offstage, and she enters—pastel Chanel sweater set, navy pants, waved platinum-blond hair, whitened face, blue-mascaraed eyes, and lipstick drawn into what Capote called "a flounder mouth"—looking like a winsome hybrid of Jean Harlow and Minnie Mouse.

To spend time with the Matthaus is like listening to a vaudeville version of Beauty and the Beast. He growls, she coos. If she's smoking when he enters the room, she shoves the ashtray and lit cigarette under the coffee table while he sniffs the air suspiciously and speaks of passively acquired cancer. He criticizes her excessive makeup; she says all she needs is a face-lift. "Walter says he's going to leave me if I get a face-lift," she informs me. "I say, 'Fine, that'll kill two birds with one stone.' " When Mary Jackson, one of the two housekeepers who have been with the couple for decades, knocks over and shatters a glass lamp in the shape of a rosebud, Walter Matthau calls out genially, "Hold for your laugh, Mary." Carol flutters over to inspect the damage: "It's all right, Mary. Nothing is forever."

Except, she might add, her passion for Walter Matthau. "I think the reason I still love him is I have no communication with him," she tells me over mini hot dogs at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel. "We never had any communication. I've always loved him for all of his maleness." The man you love, she believes, is a woman's "real mirror. You know what you are by the way a man throws you back at you."

All-consuming love is Carol Matthau's religion, a creed deeply influenced by her favorite movie, the Laurence Olivier-Merle Oberon version of Wuthering Heights. Accordingly, life for her has (Continued on page 198) (Continued from page 166) been built around the search for Heathcliff, and her ultimate role model is Oberon's Cathy, because, she whispers, "in the bleakness of the moors, she's the light."

She regrets that she'll never make it to the moon, the place Truman Capote once told her she must have come from.

Bleakness is something she knows about from her early childhood; her first memory, she says, is of hunger. Though her mother, pregnant at sixteen, married a teacher (who was not Carol's father) before Carol's birth, she walked out on him after she brought her second daughter home from the hospital two years later. Writes Carol: "The man pointed at me and said, 'Now we can put that one up for adoption.' My mother said, 'Hold the baby just for a minute.' She got her coat and her purse and lots of blankets, wrapped me up, took the baby, left, and never went back." She consigned both children to foster homes, visiting them regularly, and then, after marrying the wealthy Charles Marcus, introduced them—first Carol, then eight, and about two years later Elinor—into his household. Marcus—by all accounts a compassionate, generous-spirited man—adopted both girls.

Years later, for the author's blurb on the dust jacket of The Secret in the Daisy, Carol would write, "All my life I have been preoccupied with the problem of not permitting myself to settle down into the comfort and convenience of being nobody, which has always scared me, and still does." The sentiment dates back, she says today, to those years shuttling among foster homes, in which she aspired "to total anonymity, because you didn't know these people, and life was full of dangers. . . .That's who I was, nobody. And having been nobody, I wanted to move away from that, from those shadows."

Rosheen Marcus, now eighty-four, remembers things a bit differently. A gravelly-voiced woman with a sparsely made-up, creaseless face and a doggedly unsentimental manner, she lives in a tidy one-bedroom apartment on Park Avenue adorned with family photographs and grand portraits which suggest the great beauty she was. "You know, she wasn't in so many of those foster homes,'' she says, adding that Carol spent much of that period with her mother, a White Russian who married a French concert violinist, and other relatives. "I'm too old to worry about what you're going to say about me, and I don't care. . . . But I'm just telling you now that's terribly exaggerated.

"I don't know why people like to disclose things about themselves," she continues, pondering the reason anyone would write an autobiography. Of her own history, she admits, "Even my children guess at a lot of things, you know." Most significant among these is the question of Carol's paternity. When I remark that Carol's real father must have been extraordinary, Rosheen, exhaling smoke, answers quietly, "He was. . .But I can't disclose that." In fact, Carol had always assumed that she shared a biological father with her half-sister and didn't know different until Elinor told her on the night before Carol gave birth to her first child. She says she has now given up questioning her mother on the subject. "You see, the reason I suppose that I didn't go after it was I had the most wonderful father who ever lived. And it was by his choice."

Charles Marcus, the man whom Carol still refers to as Daddy, was a dapper figure with an incisive mind, who oversaw technical innovations in aviation for Bendix and, later, Hughes Aircraft. Carol learned early that he respected intelligence, and she would memorize difficult words to impress him in conversation. "He was mad about her," recalls Elinor. "Intellectually, they had a thing going, and I couldn't get in there." Of Carol's relationship with their mother, whom she describes as a glamorous, couture-dressed creature out of a Kay Francis movie, Elinor says, "My mother lived through Carol. She was, I suppose, everything my mother would love to have been if she had had the opportunity to grow up in great wealth."

Both Rosheen and Carol say the bond between them was intense in those gloriously affluent years before Carol married in 1943. Rosheen separated from Marcus in the early fifties and went to live in Europe for many years, where she went through, Carol says, "lots and lots of beaux. And I always knew how much money they had by their height. She liked tall men. . . .If they were short, I knew they had billions." (Of one dandyish suitor Carol is said to have remarked, at a time when relations were tense, "I think he's trisexual—men, women, and my mother.") Though Carol remained close to Charles Marcus until he died at ninety-nine in 1983, Rosheen concedes her daughter has "kind of drifted away" from her in the succeeding years.

As a child, Carol says, she adapted quickly to the dazzling luxury of a fully staffed, eighteen-room flat. "You see, I never adjusted to the [poorer] beginnings—never." She attended the National Park Seminary in Maryland and the Dalton School in Manhattan, and with her white-skinned prettiness, startlingly exaggerated—even then—by makeup, the girl known among her friends as "Baby" became a much-photographed fixture at the New York debutante balls and the Stork Club. It was in this period that she met two girls, both born famous, with whom she would form lifelong friendships—the heiress and subject of America's most famous custody trial, Gloria Vanderbilt, and Oona O'Neill, the daughter of the playwright Eugene O'Neill. The relationship among the three beauties, over the years, has assumed mythic proportions, reaching a culmination in Trio, a book written in 1985 by Carol's son Aram Saroyan.

But the concept of a tightly bonded threesome is, Gloria Vanderbilt says, a fabrication. "Carol really invented that," she contends. "Because Carol and I were always the closest, closest friends. And she and Oona were very close. And Oona and I kind of looked alike. And she just sort of put it all together. I mean, I never really had a conversation with Oona of any depth. . . .It used to kind of annoy me, but I thought it gave Carol pleasure." "It is a myth," concedes Carol. "I don't know who created it. . . .The real story is, I was Gloria's best friend, and I was Oona's best friend, and neither was the other's best friend. I tried hard to smooth things over between them, but they had such different pursuits." Nonetheless, the parallels are striking. Each was haunted by a sense of fatherlessness—Gloria lost hers in infancy, and Oona was ignored by hers from adolescence on—and would go on to marry a much older, publicly acclaimed genius. Gloria, of course, wed Stokowski; Oona, Charlie Chaplin. But the first to claim her man of renown was Carol, who, at seventeen, met thirty-three-year-old William Saroyan on a trip to Los Angeles for Gloria's wedding to her first husband, agent Pat Di Cicco.

Saroyan was then at the peak of his celebrity, having recently won (and refused) the Pulitzer Prize for his play The Time of Your Life and consistently charmed the critics with his sparely rendered, sentimental evocations of his Armenian-American childhood. The pair were introduced by a celebrated Lothario, Artie Shaw, with whom the still-virginal Carol had had a brief, celibate fling. ("There were two people in my life like that," says Shaw. "Carol was one, Judy Garland was the other, both of whom were my dearest, beloved little girls.") In Saroyan, Carol felt, she had found her Heathcliff. "Before him, all I knew were just those really nice darling boys. . .great manners. . . .all sort of the Eastern Seaboard elite. And they were very boring. Then when I met this man who looked just like a dark gangster, and he was so old, I thought, That's wonderful."

A year later, against her adoptive father's wishes, they were married. "Oh, Daddy just went crazy," says Rosheen Marcus. "But Carol said, 'Mother, if Daddy doesn't let me marry him, I'm going to kill myself,' and all that business. So I just went along with her." Gloria Vanderbilt says she had never seen anyone so much in love. "When Bill went overseas [in World War II], Carol was like Saint Sebastian with the arrows. She cried all the time."

Friends now say they could have predicted the marriage would be a disaster. Certainly, there were warning signs early on. Saroyan once broke off the engagement after receiving a series of cleverly worded letters—cribbed by Carol from love letters the young J. D. Salinger had sent to Oona O'Neill—which he felt destroyed his vision of an innocent, unaffected girl. And as Rosheen Marcus observes, "Bill didn't realize he was marrying a little debutante, who was very spoiled and didn't know anything about housekeeping or cleaning or things like that. He should have married a nice little peasant girl, you know." Nonetheless, Carol worked hard to comply with Saroyan's expectations, even becoming pregnant before their marriage to assure him that she was fertile. "That was the one thing that got Oona," she says. "But when you love someone that way, you can make a logic for anything." She bore him two children—Aram, in 1943, and Lucy, in 1946—and cloistered herself with him in a two-story house in San Francisco, scrubbing floors and doing the laundry while he worked upstairs. Visitors were not encouraged. Elinor Pruder remembers visiting them at that time and being asked to leave the house, "because I made scrambled eggs and put too much milk in them or something. And he said, 'That's it. Out.' "

People who saw the couple together describe Carol with the same adjectives: quiet, timid, frightened. Carol speaks of Saroyan today as a man given to sudden, explosive rages and financially devastating bouts of gambling. "I always knew that he loved me as much as he could love. But then, it's true that to have him love you is like saying the SS men want you." He was, she continues, "a victim of his distrust. The more he loved me, the more he had to hate me. He hated that feeling that he had to have me." She was, she feels, merely a "prop" in his life. She remembers sneaking in to read his journals every morning when he went to the bathroom, and discovering "the biggest shock of my life. It was completely falsified and made up. With him as the hero, of course. . . .This great man in this horrible world."

That is more or less the take provided by Saroyan himself in the novels and essays he wrote about Carol from the fifties on. In them, he presents a downtrodden, hardworking artist striving for the tolerance of a shallow, superficial wife, who pines for pretty dresses and fancy friends and is desperate to be told she is loved. Carol acknowledges the truth of the latter part of the description—she remains a woman in endless search of approbation and is known to ask her friends repeatedly if they love her, if she looks pretty, if she did the right thing. But the rest of Saroyan's version she firmly denies. He was, she says, "a serious liar."

Saroyan would level the same accusation at Carol, and there is, throughout his writings, the cryptic suggestion that he was deceived by her in some unspeakable way. This appears to be rooted in the fact that she told him—in bed—she was Jewish after they had been married for years, at a time when Saroyan was hounding her to have another child. An inveterate antiSemite, Saroyan, Carol writes, ripped the covers from the bed and said, "You're a Jew bastard? . . .I don't believe it. Look how perfect you are, all white and pink like a rosebud."

Carol finds it difficult to believe that Saroyan could not have known she was Jewish. And she disputes Saroyan's biographers' contention that this was the principal reason he left her. It was, she says, much more simple than that: "I began to disagree with him. . . .Before, I couldn't think of anything good enough to say to him. And, you know, a man loves a woman who doesn't speak. I suddenly had a few things to say, and he went all to pieces." When he divorced her, in 1949, she was twenty-four years old.

Less than two years later, Saroyan began courting Carol again. She had become involved with a married man in New York she identifies in her book only as "the artist" (because, she says, his widow is still alive), who had taught her love could be more, well, fun than she had suspected, and she resisted her ex-husband's overtures. Artie Shaw, whom Saroyan asked to be the matchmaker, remembers the reunion he set up in Carol's New York apartment. "He was sitting with her, and she was looking frightened as hell. . . .Bill was deaf, you know, so he talked in a very loud, gruff voice, and he's yelling, 'I love you, goddammit, I love you.' And I said, 'Bill, Christ Almighty, your words say, I love, and your voice says, I hate.' "

Still, for reasons she cannot fully explain to herself, she did remarry Saroyan, an event heralded with a splendid star-studded party given by the Chaplins in Los Angeles. The marriage lasted barely six months. Before she walked out on him, she says, she became the ultimate wife, making his life as nearly perfect as it could possibly be. It was, she says, the ' 'only really calculated terrible act of my life."

Though she was supporting two kids (Saroyan's child-support payments were erratic, and she had refused alimony), Carol blossomed in her unmarried years. She landed parts in plays on Broadway, published a novel and a short story, and hung out with Capote, Gloria Vanderbilt, and the young Kay Kendall, whom she'd met on a trip to London and whose courtship by Rex Harrison she helped engineer. And she was certainly no longer silent.

Maureen Stapleton describes the shock of hearing provocative obscenities delivered in this "exquisite, sweet tone." Carol herself confirms a memorably salty encounter with Lawrence Langner, the very proper head of the Theatre Guild, at a dinner party. Langner, she says, "was boring Laurence Olivier to death. And, of course, I was with Olivier. He was Heathcliff, my God; I loved him more than life. And I could see that he was bored. So I said [a high, fluty voice], 'Oh, Mr. Langner, show us your dong.' And Olivier was thrilled. Mr. Langner was not thrilled at all. He never spoke to me again."

Other men, however, found the effect entrancing. "She was very good with boys," says her longtime friend Leila Luce, the wife of Henry Luce III. "I remember there was this terrible boy in California, going on and on about how wonderful he was, how rich, how famous, how talented. . . .And Carol just said, 'And what else do you do?' " Luce also recalls that once, when she was visiting Carol, Frank Sinatra called at two in the morning to invite her to a party in his hotel room. "I don't believe it," Carol said after the speaker identified himself. "Let's hear you sing."

Two other men, both married, were accorded more attention. Of the writer James Agee, whom she met in the early fifties while still in California, she says, "I don't think anybody ever loved me that much." In her book, she describes how he learned to play her favorite Mozart piano concerto for her birthday present and encouraged her in her writing. Nonetheless, she says that because Agee had a heart condition and she was afraid he'd die in bed with her she never slept with him.

Nor, she swears, was her relationship with the English critic Kenneth Tynan— whose first words to her, she says, were "Will you come to England and marry me?"—ever consummated, even though the pair traveled in Europe together and shared a bed. "Walter didn't quite believe that I hadn't," she says ingenuously. "He said to Shirley MacLaine, 'Do you know what a liar Carol is to tell me she never actually really had an affair, although she'd been in bed with Kenneth Tynan?' And Shirley MacLaine said, 'She's not lying. That's the very same thing that I did.' I really had a love for him. And he was funny. But in a dark room, I don't know .. .something in me said, 'Uh-uh.' There was just a feeling you were going to invade new territory."

She very happily, however, bedded a third married man—Walter Matthau, a rising Broadway actor she met when they both appeared in George Axelrod's Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? in 1955. "I liked the way she said the word 'fuck,' " recalls Matthau. "She used the word, which was intriguing for a naive young man, because girls who would use it would obviously be easier to fuck. And she pronounced it f-o-c-k, so that gave it a little class." In turn, Carol, who says she had no intention of remarrying after the Saroyan debacle, saw in Walter the perfect one-night stand, something which dissolved into a four-year-long affair before he finally divorced his wife.

"Everything about her was pleasant, amusing," says Matthau. "Except her makeup, which was a constant obstacle course. I used to go home with it all over my clothes and all over my face. I think once, at two o'clock in the morning, I walked past a couple and they jumped back in fright, seeing this white makeup on this maniac man walking down the street." It is a habit, he notes mournfully, she has persisted in. ''Why does she put it on as if she were doing a takeoff on Marcel Marceau?" he asks, adding simply, "I think she wants to be noticed."

Carol married Walter Matthau in 1959, thus institutionalizing what Lillian Ross calls "one of the great love stories of the century." The marriage has survived the heady ups and downs of his career in Hollywood, his life-changing heart attack in 1966, her years-long struggle with malabsorption, and their respective addictions to shopping (Tiffany's is her favorite store) and gambling, two things she believes are cyclically interlocked. That she twice married gamblers still baffles her. "I guess it's because they're thumbing their nose at a moneyed society and the Establishment."

From the mid-sixties into the early eighties, Walter Matthau reaped millions (as well as an Oscar and two additional nominations) as one of Hollywood's top comic actors in such films as The Odd Couple, Kotch, and The Sunshine Boys. Much of his wealth, sighs Carol, went straight to the bookies, and she made a point of buying houses (in addition to the Pacific Palisades place, they own homes in Connecticut and Malibu), because "they aren't liquid." Walter's gambling, she says, has confirmed her long-held belief that there is no such thing as "security." She adds proudly that she has never had a savings account. Only once did she manage to save money on her own— $40,000, which she kept in a safe-deposit box. One afternoon, when she opened it to put in more money, she found it was empty except for a picture drawn by Matthau "of somebody crying, and at the bottom it said, 'Sorry, Darling.' "

Watching a basketball game, on which he's placed a bet, in the kitchen ("I picked every winner today, but my bookie's out of town, so I can't bet any good amount"), Walter Matthau talks about his marriage. "I'm a total male chauvinist," he says. "I want my wife to be the prettiest girl in the world and have this beautiful little apron, bakin' me a wonderful pie." He says he could never leave her, because "she always surprises me," adding, "She has an unusual slant, and it changes. One minute she's Marie Antoinette, the next she's Madame Defarge, planning the revolution."

Elinor Pruder, who was with the couple on location for Pirates, explains why there was no thought of flying Carol to an American hospital even when she appeared to be seriously ill. "If Carol had left, Walter would have left. He's her shadow. You know how he comes across. But Carol is the strong one." Carol agrees that her primary role is to be Walter's adoring, and sustaining, wife. "I guess I'm of the generation that still believes in that, because that's how you achieve love. And you can't achieve it by making a man miserable." She adds of her husband, "I can still feel that first love. Because his duality is just the opposite of Saroyan's: Saroyan was magnificent in the living room and a horror upstairs. Whereas Walter is the most romantic man, and that's what makes things so beautiful to me in bed."

Correspondingly, she admires Gloria Vanderbilt as "the most romantic person I know. . .she aspires to be in love all the time." But she admits that with Oona Chaplin—who consecrated her life to her husband, Charlie—"the price was too great." "Oona was one of the most brilliant people in the world," says Carol of her friend, who died last September. But after Chaplin, who was thirty-six years Oona's senior, died in 1977, his widow was left with a vacuum in her life she chose never to fill, instead numbing her grief with alcohol. Oona had never been more than a social drinker before, says Carol, but she acquired the dependency during the period of Chaplin's final illness, when she would wake him every hour and a half to take the meticulous, dignified man, who was scared of incontinence, to the bathroom. "What would you do if you had to get up every hour and a half? You couldn't take sleeping pills. You'd take a swig of scotch. And that was the beginning of it." Still, says Carol, her friend never seemed less than piercingly lucid to her. And in the last weeks of Oona's life, she would help Carol edit her autobiography on the phone. Carol's voice wavers when she speaks of Oona. "When Oona died, I began talking to her: 'How could you? How could you go? Where are you?' "

Discussing Oona's conflicted relationship with her children, Carol writes in her memoirs, "I think the notion that children are your life is the biggest myth in the world. They're not. Love is your life." Her own experience with motherhood has been complicated. While she has sustained a close and loving relationship with her son by Matthau, Charlie—the twenty-nine-year-old director, who lives next door to the couple and who describes his mother as "always my best friend"— she has not spoken to her children by Saroyan, Lucy and Aram, in more than two years.

Carol will say only that she did the best she could in raising them under strained circumstances, and that she and Walter gave them extensive financial and vocational support until they were well into their forties; finally, she says, their demands became "impossible." She adds succinctly, "The children you're asking me about are not children. They're people in their mid-forties. And I don't like them. And the reason I don't like them is they don't like me. And I really don't like anyone who doesn't like me."

When her mother's statement was read to her, Lucy, an actress and journalist, responded, "I love my mother very much. I've always wanted her to love me as well." Aram, who collaborated closely with his mother to create Trio in the mid-eighties and who, in his autobiographical Last Rites, refuted his father's long-running vilification of her, would not comment.

Elinor Pruder believes the gap was created, in part, by the fact that her halfsister is "still carrying that little girl Carol inside of her, and she tends to protect that little girl." While she thinks Carol worked hard at playing the conventional mommy, she was too exotic to fit the role, something Pruder believes baffled Lucy and Aram. (This was obviously compounded by their father's ongoing diatribe against her.) She adds hesitantly, "I think, to begin with, having a mother that's as glamorous as Carol.. .and having a family that are well-off—they don't even realize it, but come on, the Matthaus are very well-off.. .1 think there's always resentment, hostility, demands made from one's children."

Nonetheless, Carol's friends describe her as a woman of unstinting beneficence. "She creates an atmosphere around her that's.. .loving," says Maureen Stapleton. "And she's so generous it's ridiculous. . . .She makes it seem like you're doing her this great favor to take this mink coat off her back." Artie Shaw adds that, above all, "Carol is a person who needs to be loved. She gives a lot of herself."

When Saroyan was writing his "Carol" books, his publishers would send her material they feared was libelous. She had a form letter she sent right back. It read: "Be my guest." Similarly, when the notorious "La Cote Basque" chapter of Capote's Answered Prayers was published, she did not—unlike many of the other real-life characters portrayed in the story—feel she had been betrayed, although she admits she never really said any of the things Capote attributed to her. "But he told me what they were, and I said, 'Oh, well, I would have said them, if I had known.'. . . Anyway, he said I had skin like a gardenia, and I felt like a princess.

"Writers write," she continues. "They write lies; they write it the way they see it. Or the way they want to see it. Or maybe the way they want other people to see it. . . .I don't take it too seriously." Now, of course, she is presenting the world with a Carol Matthau's-eye view, and—while her book includes a chapter on the importance of "civilized lies"—she swears that everything in it is true to life, at least as she remembers it.

She told me these things on our one day together outside of her Pacific Palisades home. She had had to attend a ladies' Valentine's Day luncheon given by Barbara Davis, the wife of tycoon Marvin Davis, at the Bistro Gardens in Beverly Hills at the ungodly hour of noon. "Can you believe it?" she had complained to me the night before. "I might as well start getting dressed now." I had waited for her in the restaurant for a good forty-five minutes, while a procession of leggy females— Sherry Lansing, Cristina Ferrare, Jaclyn Smith, Audrey Wilder, among them— filed past, in a numbing series of variations on the short, streamlined power suit. Then there was Carol. In a deep-pink pantsuit, a straw hat wreathed in artificial roses, red high-heeled boots, carrying a heart-shaped red straw bag. (Valentine's Day and Halloween, she had told me earlier, are "my days.")

She said she hadn't slept much the night before. She seldom does, since that is when she writes, rehangs the pictures in the house, calls her friends in other time zones, or just stares at the ceiling and arranges her thoughts. But she seemed focused, in her typical fragmented way, as we browsed for an hour in Tiffany's— where she was greeted by the staff like Dolly Levi entering the restaurant in Hello, Dolly!—and cruised the designer boutiques on Rodeo Drive, where she gravitated toward anything frilly and pastel.

As usual, she was full of things to tell me, stopping periodically to ask if she was really giving me what I wanted, or on what days—in the times I'd seen her—I thought she'd looked prettiest. I learned about the unanswered letters she writes daily to Gorbachev, one of her heroes, and her obsession with spies. (The license plate of her Rolls Silver Shadow reads "MI6," and she is finishing up a book on Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, the head of German intelligence during World War II and a man she firmly believes was a double agent who changed the course of history.) They interest her because "they make a commitment to a vacuum."

By the end of the day, she was visibly flagging, and I was relieved when she announced that her husband had asked if I would drive her home in her car, because "Walter worries I'll fall asleep at the wheel." But when we got to the Rolls, she slid into the driver's seat. I think I screamed when the car lurched onto Wilshire Boulevard, because she looked at me and said plaintively, "You don't trust me, do you? They've gotten to you. They've reached you."

It was a memorable ride. We drove most of the way down Sunset Boulevard in the middle lane, because, she explained, "it's the best place to be. That way they can't ambush you." As the car moved along convulsively, she conceded, "The only one who thinks that I'm a superb driver is Maureen [Stapleton], because she's absolutely drunk to the gills. . . .Yes, driving in bumps. Walter criticizes that, too. But I mean, as a danger, I don't think there's a problem." We reached Pacific Palisades uneventfully; no one had even honked at us.

Carol Matthau will tell you that though she's never moved fast, or in a straight line, she nearly always reaches her destination. She regrets that she'll never make it to the moon, the place Truman Capote once told her she must have come from. But she plans, before she dies, to spend a long time on the Trans-Siberian Railroad.

"I'll go back and forth as many times as I want. And I'll take a lot of peanut butter, and Walter's old sweaters, and just sit and look out the window. And see all that space, that snow, that ice, that lace."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now