Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA mystery woman in the Laci Peterson murder, lunch with Johnnie Cochran, and Alfred Taubman's post-prison battle: as the author makes his monthly report, ripples from cases old and new also include an unexpected letter concerning a juror in the trial of his daughters killer

JULY 2003 Dominick Dunne Antoine Le GrandA mystery woman in the Laci Peterson murder, lunch with Johnnie Cochran, and Alfred Taubman's post-prison battle: as the author makes his monthly report, ripples from cases old and new also include an unexpected letter concerning a juror in the trial of his daughters killer

JULY 2003 Dominick Dunne Antoine Le GrandWe've won the war and watched the troops come home and reunite with their families in very moving tableaux, and everyone is glad that it's over, but there seems to be no sense of victory in the air, no merriment at having won. From the start, winning was a given. At 18, I was a soldier in combat in Europe during World War II. How different everything was. When that war ended, there was international jubilation such as no one had ever seen. People wept and cheered and hugged strangers while bands played "God Bless America" and fireworks lit up the sky. We loved our land. We loved Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. It was a delirious moment in history. That kind of exhilaration has been absent this time around, and maybe it's because there's such a thing as being too powerful. However, life is back to normal. There are things besides Iraq on television. I'm drinking all that Poland Spring water I stocked up on in case New York got bombed, and I've given away the duct tape I was prepared to seal my windows with. I kept the face mask, however, in response to the SARS scare.

One result of the Iraq war was that I grew to dislike Jacques Chirac, the president of France, especially after seeing him interviewed most revealingly by Christiane Amanpour on 60 Minutes. I think it will be interesting to see what happens when the next couture collections take place in Paris—whether the American fashion world will storm Paris as usual, or whether there will be a noticeable cutback.

Recently I had lunch at Michael's, the popular hangout for the publishing crowd, with the defense attorney Johnnie Cochran. It was the first time we had met face-to-face since the day of the verdict in the O. J. Simpson trial. I think it's safe to say that we weren't pals during that trial, where he was in charge of Simpson's defense team, although I always remained on pleasant terms with his handsome wife, Dale. Henry Schleiff, the chairman and C.E.O. of Court TV, on which I have a series and with which Cochran has an ongoing affiliation, came up with the idea of our having lunch together, after I wrote in my April diary that Cochran had spoken nicely about me in an upcoming Court TV biography of me. It seemed like a good idea. When you go through a yearlong trial, you get to know everyone, no matter what side you're on. And there are no two ways about it: Johnnie Cochran, one of the justice system's most charismatic figures, was the undisputed star of the Simpson case. The courtroom was his, not Judge Ito's, to rule, and rule it he did. He even upstaged his client, who had spent a lifetime being the center of attention. Some of the things Cochran did and said back then outraged me, but I could never stop watching him. It's not much different if you're having lunch with the man. Everyone in the restaurant was aware of his presence. We didn't talk much about O.J.; he hadn't seen him in two years. I didn't bring up the 911 call Simpson's daughter, Sydney, recently made to the Miami-Dade police after a family fracas. We discussed the standstill in the Phil Spector case. We also talked about the incredible coincidence that Chandra Levy and Laci Peterson, the two most famous missing persons in years, both came from the city of Modesto, California, and that they both turned up, after several months, as decomposed corpses. Cochran said the Modesto police must have evidence we don't know about if they can go after the death penalty for Peterson. Cochran is very funny, so we had a few laughs. At one point he borrowed my cell phone to call Dale in California. He said, "I'm here with a friend of yours," and handed me the phone. It was a nice moment, and a nice lunch—and a perfect way to get rid of old grudges.

The tragic discovery near Berkeley, California, in April of the washed-up remains of Laci Peterson, minus the head and legs, and the fetus of her unborn son, Conner, effectively ended the around-the-clock war coverage on television. Scott Peterson, after his arrest, became as reviled as O. J. Simpson had been a decade earlier. Peterson was front-page news and the lead story on television, with his dyed blond hair, his red prison uniform, and his cuffed wrists. The popular defense attorney Mark Geragos, a lawyer for Winona Ryder and Gary Condit and frequent talking head on Larry King Live, stunned everyone when he replaced Peterson's public defenders as lead counsel. The next time Peterson appeared, he was in a brand-new blue suit and had no restraints on him. His dyed hair was returning to its normal color, and he looked like a different person. Geragos, in a bit of pre-trial posturing, appealed publicly to a mystery woman who allegedly has important information about a credible suspect in the murder to step forward. He promised her anonymity. This gesture was clearly intended to create a reasonable doubt in people's minds. A rumor also arose that the defense might pursue a theory that members of a satanic cult had murdered Laci. However, so far my original opinion on this case remains unchanged.

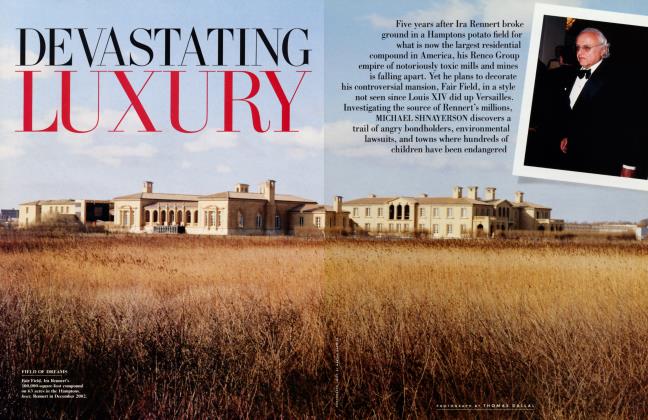

Some friends feel Taubman may not hold on to his company.

Twenty years after the trial of the man who killed my daughter, Dominique, I had a letter from one of the jurors. Actually, since the juror is now 90 and unwell, her daughter wrote the letter for her. My daughter's killer, John Sweeney by name, although he subsequently changed it to John Moira, got a slap-on-the-wrist sentence of six years, which was automatically cut to three, and, with time served, he got out in two and a half, to the utter astonishment of everyone who covered the case. The juror said she had served on several prior juries and had always had great faith in the legal system. "All that changed after Sweeney's murder trial," her daughter wrote. Her mother felt "completely duped" by the slant of the evidence presented. She felt that the jurors had been given only half of the story. "She still damns the judge for excluding the evidence that would have helped the jury come to a just verdict." The juror never served on another jury. I wrote her back, thanking her for her letter, and I sent copies of it to Steven Barshop, the prosecutor in the case, as well as to many of the people I knew who had attended the trial.

I have become acquainted with a fascinating woman, a new figure on the big-time scene and a great curiosity to Washington's Old Guard, who seem to feel that she is trying to buy her way into their rarefied circles. Her name is Catherine Reynolds, and she recently gave $100 million to the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. She began to stir controversy two years ago, when she pledged $38 million to the Smithsonian Institution, only to make headlines by rescinding her offer a year later, after it became apparent to her that the Smithsonian's plans for her enormous contribution did not take her wishes into account. With a letter asking me to have lunch with her and her husband, Wayne Reynolds, at the Four Seasons restaurant in New York, she sent along a videotape of Mike Wallace interviewing the two of them on 60 Minutes, where she discussed her disenchantment with the Smithsonian. She is a good-looking, no-nonsense lady who appears to be in her late 40s. She has a 10-year-old daughter and lives in McLean, Virginia. She was dressed expensively but conservatively, and wore very good pearls. Her husband is not a member of the Reynolds tobacco family or the Reynolds aluminum family. "I didn't marry money," she said to Mike Wallace. "I didn't inherit money. I actually made it." Mrs. Reynolds made a fortune by means of a system of underwriting student loans. She had previously given $10 million to the Kennedy Center and $1 million to Ford's Theater, and had underwritten exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. She is the largest benefactor of the arts in Washington since the days of the munificent Andrew Mellon and his son, Paul. She is on close personal terms with heads of state and Nobel Prize winners.

By chance, I had a previous but remote connection to Wayne Reynolds, whom she married in 1999. I had met him in 1994 in Las Vegas, Nevada, when I was one of the honored recipients of a golden plate from the Academy of Achievement, an unpublicized nonprofit organization which brings outstanding students together with people of achievement. The academy was founded by Wayne Reynolds's father 40 years ago. Each year the event is held in a different location. I'll always remember that extraordinary weekend in Las Vegas. I was late for the dinner in the ballroom because I simply couldn't tear myself away from the television in my suite, to which I was riveted by the coverage of O. J. Simpson and Al Cowlings during their freeway chase in the white Bronco.

When we met for lunch at the Four Seasons, Wayne Reynolds remembered that that evening had led to my covering the Simpson trial. I had declined to attend this year's academy event in Washington because it conflicted with Vanity Fair's part in the Tribeca Film Festival in New York, but in the end I was able to adjust my schedule so that I could go to the opening ceremony, and it turned out to be a memorable night. With 225 of the smartest graduate students from 44 countries in attendance, we met in the Supreme Court chambers, where Justices Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg talked about the Court's controversial 5-4 decision that gave the last election to George W. Bush. Secretary of State Colin Powell stopped by on his way to the airport to fly to Madrid to meet with Jose Maria Aznar, the president of Spain, and then to Syria. He defended the war in Iraq and took a few questions from the students. The dinner was held in the Supreme Court, where the soprano Kathleen Battle sang for us. I was seated next to Catherine Reynolds at Sandra Day O'Connor's table. My friend Scott Berg, a former recipient of the golden plate and Pulitzer Prize winner for his biography of Charles Lindbergh, was also at the table. He was scheduled to speak the next morning at the Air and Space Museum, beneath the Spirit of St. Louis. To my right was a graduate student from St. Andrews University in Scotland. I asked her how she had been chosen. She said they had not been told. After dinner we boarded buses to the Lincoln Memorial, where the 87-year-old Pulitzer Prize winner Herman Wouk stood on the brightly lit steps in front of the statue of Lincoln. "The first thing I want you to do is forget about that hunk of marble. This was a guy," he said and went on to tell what a guy Lincoln was. We then moved on to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, where Neil Sheehan, another Pulitzer Prize winner, for a book about that war called A Bright Shining Lie, spoke about the men who had fought in it. "When you stand here, you stand on holy ground," he said. That was the first of four evenings dedicated to American history. Catherine Reynolds was quoted in The Washington Post as saying, "The reason these people are here, because none of them have to be here, is because they actually believe that one individual can make a difference in the world."

Alfred Taubman got out of prison on May 15, after having served nine months of his year-and-a-day sentence for collusion in the Sotheby's-Christie's price-fixing scandal. He was released at 9:15 A.M. and met by his son Robert and his controversial wife, Judy, who had flown out from New York. They flew on Taubman's private plane to Detroit, where he had made his fortune in malls—he has 30 of them nationwide—and where he maintains a fully staffed mansion in Bloomfield Hills. He had several leisure hours to spend with his family in the privacy of their home before he had to check into a halfway house. From all reports, his prison was like the Ritz compared with the grim halfway house, which is called Monica House, a "squat, brick building perched over a freeway," as Jennifer Dixon, who sat next to me at Taubman's trial, reported in the Detroit Free Press. "It's a real dump in northwest Detroit, the worst part of the city," said Christopher Mason, who is writing a book about the case called When the Gavel Falls. During the months of Taubman's imprisonment, his friends would fly to Rochester, Minnesota, to visit him at the federal facility there. Everyone gave him high marks, reporting that he did not complain about life in prison but made the best of it. He even formed a bridge club. Right up to the time of his release, however, he continued to insist that he was innocent, telling one person I know that he had had no knowledge of what was going on at Sotheby's when he was chairman of the board and Diana Brooks was running the company. On the night before his release, I went to a party in New York which Taubman certainly would have attended if he had been a free man. It's an annual event, and he was there last year when the host made a toast to him and wished him luck. This year everyone was saying, "Alfred's getting out tomorrow," and speculating about whether the Taubmans would resume the high-powered social life he had so enjoyed. Most people did not think so. Taubman was released from Monica House on May 23, but he is not allowed to leave his Detroit residence for a month. The first thing on his agenda is to fight an attempted hostile takeover of Taubman Centers, Inc., by Mel Simon, head of Simon Property Group of Indianapolis, a despised rival who used to be a friend. The takeover effort began after Taubman went to prison. A financial analyst told the Detroit Free Press that Robert Taubman would "slit his throat rather than sell out to Simon." Even some of Alfred Taubman's friends feel he may not succeed in holding on to his company.

A rumor arose that a satanic cult had murdered Laci.

The lives of the children of the famous, I have observed, may I have their perks—good clothes, big houses, nice cars, private schools—but in the long run they are not enviable. The suicide rate is enormous; I personally have known nearly a dozen who have chosen that route. Often the individual bears terrible anger against his or her parents. I remember one who jumped off a roof on Mother's Day and left a suicide note on a Mother's Day card. I remember another who shot himself on his father's front lawn. Many simply carry their resentment with them into middle age. Such a person was Lucy Saroyan. All of us who knew her were saddened to hear of her death last month in a motel room in Texas. Her father was William Saroyan, who in the 40s and 50s was one of the most famous writers of novels and plays in the United States, much written about in the way that Gore Vidal, Truman Capote, and Norman Mailer would be later. He even co-wrote a popular song, "Come on-a My House," which Rosemary Clooney turned into an enormous hit in the early 50s. Saroyan married a celebrity debutante named Carol Marcus of Park Avenue, New York, who was inseparable friends with Gloria Vanderbilt, a front-page celebrity from the time she was seven, and Oona O'Neill, the daughter of Eugene O'Neill, America's greatest playwright. The trio of beauties were fixtures at the Stork Club and El Morocco, and they all married much older men. Gloria Vanderbilt married Leopold Stokowski, the renowned conductor. Oona O'Neill married Charlie Chaplin. Carol Marcus married William Saroyan, later divorced him, then married him again and divorced him again.

Lucy and her brother, Aram, were the children of that marriage. About 30 years ago, Carol Marcus Saroyan married Walter Matthau, the film star. Lucy got lost in the shuffle. People liked her, though, even after she got to be trying. She had a brief glamorous period. Nora Ephron, the writer and film director, remembers her coming into Elaine's restaurant one night years ago on the arm of Marlon Brando, looking absolutely wonderful, on top of the world. But she had drug problems, and several of her romantic relationships were with well-known druggie stars. She was one of those people for whom nothing ever worked out. She wanted to be an actress or a writer, but it never happened. She could be hilarious, but there was always an undertow of sadness in her character.

The last time I saw her, she was selling books at Book Soup on the Sunset Strip in Hollywood. She said joyously, "Guess what. I'm in the program!" She meant that she was clean and dry. We hugged.

But it didn't last. Her friends heard that things had gone bad.

She had a new guy, younger, and they were moving to Texas. She had said she wanted to be cremated and have her ashes spread over San Francisco, where she had lived during a happy period.

I learned that her ashes were buried in William Saroyan's grave.

"But I thought she didn't get along with her father," I said to a great friend of her mother's.

"Oh, darling, she was obsessed with her father."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now