Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

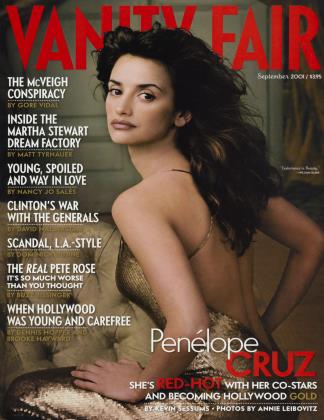

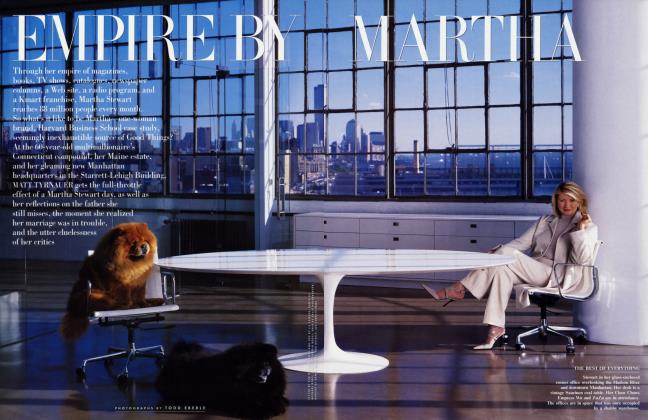

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowInvestigating the unreported death of a once prominent L.A. scion, consulting fellow best-selling novelist Sue Grafton, plugging his true-crime collection, Justice—it's a wonder the author had time for his ongoing probe into the Edmond Safra mystery, which led to a Four Seasons spank from one of Lily Safra’s lawyers

September 2001 Dominick Dunne Antoine Le GrandInvestigating the unreported death of a once prominent L.A. scion, consulting fellow best-selling novelist Sue Grafton, plugging his true-crime collection, Justice—it's a wonder the author had time for his ongoing probe into the Edmond Safra mystery, which led to a Four Seasons spank from one of Lily Safra’s lawyers

September 2001 Dominick Dunne Antoine Le GrandThe ability to suppress news has always fascinated me. How in the world does the mysterious death of a once prominent person stay out of the newspapers? But it happens, and it has just happened again. When I first lived in Los Angeles, in the late 50s and early 60s, the Edwin Wendell Pauleys were one of the families, in a league with the Dohenys, the Mulhollands, and the Chandlers, who were to Los Angeles what the Astors, Vanderbilts, and Rockefellers were to New York. Thoroughfares and buildings were named after these families. The Pauley money came from oil—Pauley Petroleum. Ed Pauley Sr. was a financial backer of Governor Pat Brown and later of Governor Jerry Brown, but he also had political allegiance to Richard Nixon. They lived in a lovely, big white Colonial house on Sunset Boulevard, at the corner of Foothill Road, in Beverly Hills. It was the kind of house I always turned to look at as I drove past. The Pauleys gave Pauley Pavilion, the sports arena, to U.C.L.A. Their annual Rose Bowl party on New Year’s Day—they bused their guests to Pasadena for the game, with waiters aboard serving cocktails and canapes—was always covered on the Los Angeles Times society page. Theirs was a different crowd entirely from what was known as the Hollywood A Group. Like oil and water, the two groups did not mix back then.

Although I was strictly part of the Hollywood show-business set, my wife, Lenny, had strong ties to the Los Angeles-Pasadena group, and we sometimes saw the Pauleys at parties. It is their son Edwin Wendell Pauley Jr.’s untimely and ugly death that was not reported in the newspapers. As I remember Ed from those days, he was handsome, glamorous, and unpopular. Girls flocked to him. He had once taken out Elizabeth Taylor, before she married the hotel heir Nick Hilton, and their flirtation gave him an added dash. Ed Pauley Jr. and Otis Chandler—whose family owned the Los Angeles Times, of which Otis would later become the publisher—were the two biggest catches in Los Angeles society. Pauley eventually married a Pasadena society girl named Vicky Geiss. Ed had the look of the rich boy in Scott Fitzgerald’s famous short story of the same name; there was an expression on his face that made his social position quite clear. But he could also be fun as well as funny, even if his wit had an edge to it. In later years, I understand, that rich-boy expression lost its validity. He was the golden boy who never fulfilled his promise. After having three children, he and Vicky divorced. There were unpleasant stories about him—that he turned mean when he was drunk, that he beat up women.

One Saturday morning in late June, I got a call at my house in Connecticut telling me that Ed had been found dead in a bathtub in a hotel in Santa Barbara. My source reported that his throat had been slit from ear to ear, and that the story had come straight from a cousin of what was left of the immediate family. It seemed that there had been drinking problems, and gambling problems, and gambling debts. There was also a suggestion that Ed had owed money in Las Vegas, and that his death may have been a hit. The body had been immediately cremated. His remains, I was told, were in three coffee cans. My source went on to say that more than three weeks had passed since the body was discovered, but that there had not been a word in either the Santa Barbara papers or the Los Angeles Times. A Pauley death from natural causes in a hospital would certainly be a news story in Los Angeles, so it would stand to reason that a Pauley death in such sordid circumstances would have made the front page.

Ed Pauley's remains, I was told, were in three coffee cans.

I said, “Let me check this out,” and I made calls to three of the most tuned-in women in high-class Los Angeles. They always know what is going on. All three said exactly the same thing, with the same shocked intonation: “ What?” None of them had heard the three-week-old story. Not only wasn’t it in the papers, it wasn’t being gossiped about among the people who had known Ed, because none of them knew that he was dead, or had heard much about him in recent years. One of the women said, “Ed’s stepmother is still alive—Bobbie, do you remember her? She married again after Big Ed died. I think she married the C.E.O. of Pauley Petroleum, and she’s still living in the same house on Sunset. I can’t remember his name. I think he died. Let me look them up in the Blue Book, and I’ll call you back.”

There was no service. There was no notification to friends, and certainly there was no obituary notice. I tracked down a woman from one of the old Los Angeles families at her summerhouse elsewhere in California. “Yes, it’s true,” she said, because her daughter knew the daughter of blah blah blah—it was one of those connections. She didn’t want to talk about it. Instead she asked, “Are they going to let that poor male nurse out of jail in Monaco?” I did that bit, then got back to Ed Pauley’s death. She didn’t want her name used. She didn’t know how it had been kept out of the papers. She said that a sanitized version was now being circulated: Ed had tripped and fallen while holding a bottle under his arm, and the bottle smashed, and a piece of broken glass severed an artery.

A few nights later, I ran into the former movie stars Arlene Dahl and Jane Powell—who had been under contract at MGM at the same time as Elizabeth Taylor—at a nightclub in New York, where we were watching Tony Danza do his song-and-dance act. I asked if they had heard about Ed Pauley. They hadn’t. “He was so good-looking,” said Dahl. “But there was something strange about him,” said Powell. “Elizabeth dumped him and married Nick Hilton. Do you remember?”

A wise widow I know, who with her late husband was a part of Frank Sinatra’s inner circle during the days when he was the king of Las Vegas, doubted the story that someone from Vegas had Ed Pauley Jr. killed because of gambling debts. “There was a time when that might have happened, but not anymore. They wouldn’t send anyone after him. The interesting thing is, what was someone like Ed Pauley Jr. doing in a small hotel in Santa Barbara in the first place?”

In the days since I heard about Pauley’s death, details have slowly come out. In the past his father had bailed him out of gambling debts, and he cut Ed from his will. Two of Ed’s children had been institutionalized. He had not spoken to his third child in 30 years. So estranged was he from his glamorous earlier life that neither his former wife nor his daughter knew where he lived. The police were unsure whether there were any next of kin.

His naked body was discovered by the police at one P.M. on April 24 at the West Beach Inn, a hotel on Cabrillo Boulevard, after an employee was unable to get a reply when she wanted to enter the room. There were two vodka bottles on the desk, one empty, the other half empty. The coroner’s report said that he had fallen in the bathroom and that broken glass had severed the brachial artery of his upper right arm. The body was not claimed for six days. His car was registered in Texas. Through a woman friend in Florida, the police finally connected Pauley to the Devereux Foundation, an institution for people with mental disabilities. One of his children, now in her 40s, lived there. The foundation made it possible for the police to contact her mother. When family members arrived in Santa Barbara, some were convinced that Ed had been murdered. The body was taken to the McDermott Crockett Mortuary for cremation.

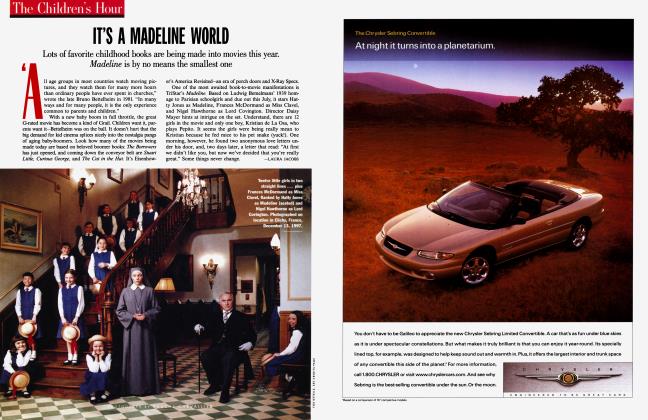

My Hollywood friend Thom Mount, adviser to the chairman of RKO Pictures, suggested I call Sue Grafton, the famous mystery writer, whose current book, P Is for Peril, adorns the New York Times best-seller list. Grafton, whom I did not know, lives in Santa Barbara when she’s not at her house in Kentucky. We got on great. She has friends in the sheriff’s department and set it up for me to talk to Sergeant Bill Turner. The story turns out to be not criminal, merely heartbreaking.

Pauley had become one of those people who were not missed. No one was looking for him. His name no longer rang a bell, and the police had no idea he was from a prominent family. Sergeant Turner told me that reporters from the local paper check the records at the sheriff’s office every day or so, but since Pauley came in as John Doe, they read right over his death notice as if he were just another vagrant. Apparently he simply bled to death, naked on the floor, either too drunk to call for help or simply not caring enough for his life to want to save it. Or both.

The Pauley mystery didn’t quite end there. A rich Los Angeles friend had more to tell me. “After Ed was cut out of his father’s will, he was determined, utterly determined, to marry a rich girl,” she said. “He came after me and begged me to marry him. I dated him back in ’65, but I soon realized he was a mean, lying drunk. He said such terrible things when he was drunk.

Ed had become one of those people who were not missed.

He grabbed me once, and I was afraid of him. A doctor friend of mine—you and Lenny used to know him—took me out to lunch. He said, ‘I understand you’re dating Ed Pauley Jr. He’s after your money. He has no money. No matter what he tells you, he does not work for Pauley Petroleum.’ So I called Pauley Petroleum and asked for him. They said, ‘He’s not here. He’s not welcome here.’”

Ed Pauley’s father was a longtime member of an exclusive, all-male organization in California called the Rancheros Visitadores. They ride together on long treks. Ed junior was also a member, and he rode with the Rancheros for 25 years. Whenever a Ranchero dies, the members gather for a eulogy. A distant former in-law gave the eulogy for Ed, telling of his tortured life and saying that he had committed suicide. Another Ranchero said that the only time Ed had ever been happy was when he was riding with the group. Whether the members took a vow of silence I do not know, but word of Pauley’s death has not spread. I am told that a prevailing theory among a certain inner group is that, after getting into the shower in the hotel dead-drunk, Ed Pauley broke a glass and slit his throat.

Los Angeles seems to have a history of minimizing the crimes and tragic deaths of powerful people. In 1929 there was scant coverage of the murder of Ned Doheny, the scion of the city’s first family, who was shot to death in a downstairs guest room of his magnificent mansion, Greystone, by his male secretary, who then shot himself. Alfredo de la Vega, a descendant of the Spanish landed gentry of Los Angeles and a popular social figure in the city, was last seen late at night in 1987 at a Sunset Strip bar in black-tie, having come from a dance in the home of one of the close friends of President and Mrs. Reagan. When he was found in his apartment the next day, there were bullet holes everywhere—in the walls, in the mirror; in him. But his murder was reported as a suicide, by people who knew otherwise, and that became the accepted version. I fictionalized the de la Vega murder in my 1990 novel, An Inconvenient Woman.

Then there was the famously underreported forgery case in 1977 involving David Begelman, the head of Columbia Pictures, and Cliff Robertson, the Academy Award-winning actor. Those were big names, but in Los Angeles their story was treated as if it were insignificant. This hapPened, however, at the time that Mrs. Norman Chandler—Dorothy Chandler, known to Los Angeles at large as Buff—was raising money for her dream project, the Music Center, where the main building would be called the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. For the first time in the history of the city, the movie crowd and the old-money crowd intermingled. Buff needed the big movie money to finish her project, and the heavy gossip at the time was that the Chandler newspaper had to soft-pedal the Begelman story or she would risk losing the movie money. It took David McClintick, a Wall Street Journal reporter, who also included the story in his 1982 book Indecent Exposure, and two writers from The Washington Post—with a tiny bit of help from me, I might add—to take the story national.

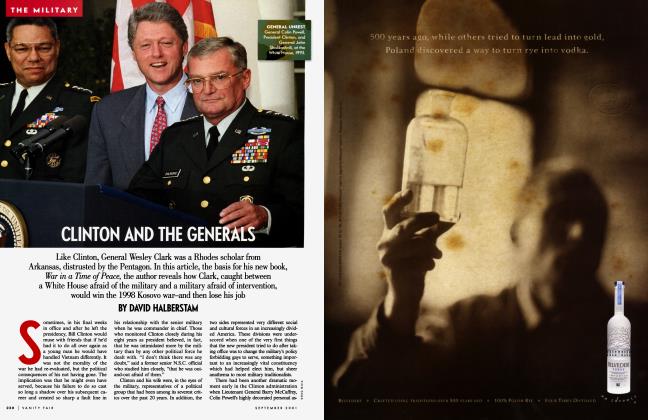

Leaving the Four Seasons restaurant after lunch one day, I stopped at the table of the former senator Bob Kerrey, who is now the president of the New School in New York, to tell him how much I admired him. He is, to my mind, a genuine hero. He had been getting flak for a revisited incident in the Vietnam War and had handled himself in the most dignified way. The nice moment we shared was spoiled by a sharp swat I received on the right cheek of my rear. I turned to look at a total stranger. “So you’re Dominick Dunne,” he said in a rather unpleasant voice, having heard me give my name to Kerrey. “I’m Stanley Arkin.” Arkin has been mentioned frequently by me as one of the lawyers for Lily Safra. His face matched the tone of his voice, and I took an instant dislike to him. “Stop using my name in your magazine,” he ordered. I think I was supposed to be intimidated. The sad thing is, I never got to finish my conversation with Bob Kerrey. Someone else had come up to him.

I have finally talked with someone who was actually at the scene of the fire in Monte Carlo that took the life of the billionaire banker Edmond Safra on December 3, 1999. We met in secret. No names will be used. My visitor lived only a few minutes away from the building that housed Safra’s Republic Bank on the ground floor and his treasure-filled penthouse on the top floor, and went there after receiving an early-morning call telling him the penthouse was on fire. Most of the damage to the interior of the penthouse was caused by smoke and water, not fire. The priceless furniture was not damaged, but some of the paintings were destroyed. What was most memorable to my visitor was that there was total access to the ground floor and stairways. There was no one in charge to monitor who was entering and exiting the building. Confusion reigned. My visitor saw Lily Safra sitting there, wearing a nightgown and a jacket that looked as if it belonged to one of her grandsons, which a butler had retrieved from a hall closet of the burning apartment. She wept over and over as she told friends and family who came to sit with her what was happening, and all the while the fire was going on six floors over her head. When the police brought her news that Edmond was dead, she broke down.

“They haven’t got anything on Blake" said Linda Deutsch.

Certain details in my visitor’s account were of particular interest to me. I have several times written about the arrival that night of Safra’s chief of security, Samuel Cohen, to whom Lily gave the key to the bathroom where Edmond and the nurse Vivian Torrente were breathing in the fumes that would shortly kill them. The Monaco police handcuffed Cohen. What I now learned was that eventually the police took the handcuffs off Cohen and let him return to the ground floor, but they did not take the key to the bathroom from him. “Why?,” I asked. The reply was an I-don’t-know gesture. My visitor had seen Cohen wandering around with the key still in his hand. “Cohen was devastated. He took it as a personal failure that Safra was dead,” he said.

As part of the elaborate security system, the penthouse had steel shutters that came down over the windows. If a fire alarm went off, the shutters would automatically rise. On the night of the fire, my visitor told me, all the shutters in the large penthouse rose except for those in the nurses’ station, in Edmond’s gym, and in his bedroom and bath.

Ted Maher, Safra’s male nurse, had been revered for his nurturing manner and deeds at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center in New York. One father, who credits him with saving the life of his premature daughter, described him to me as “a positive, strong, kind, and caring person.” But Maher was not happy in Monte Carlo, where he had to take orders from nurses less experienced than he. Members of Safra’s staff nicknamed him “the man without an expression.” “He always had a blank, vacuous stare,” said my visitor. Shortly before the night of the fire, he had gambled at the casino and carried around a bag full of chips for all to see. None of Edmond Safra’s nurses was licensed to work in Monaco. They were all hired by a corporation called Spotless & Brite Inc., the address of which was the same as the New York office of Safra’s Republic Bank. According to my visitor, “It was a dummy corporation. The nurses were employees of Spotless & Brite, as were the butlers. They came to Monaco as tourists on vacation, not as nurses. They had no working papers to work in Monaco.”

Mark Kurzmann, the lawyer representing Maher’s wife, Heidi, says, “To avoid the strict labor laws in Monaco, they brought in nurses like Ted, passing them off as domestic help.”

The case continues to fascinate people. Court TV has set up a Web site on Safra. In London, Father Fred Preston, who took the accused Ted Maher weekly Communion in the Monte Carlo jail, gave an extraordinary interview to Sharon Churcher in The Mail on Sunday. Father Fred, a former padre to the Special Air Service and Parachute Regiment, whom I once met in Paris during my initial investigation of the Safra case, described Ted Maher as “an unsophisticated man, an easy ‘patsy’ for the police.” About the knife wound on Maher’s body, which the police claim was self-inflicted, Father Fred said, “A professional soldier and nurse such as he is would have drawn blood on the fleshy part of his thigh or the upper hipbone if he was staging this. To go into the bowel at the angle and depth of the wounds on Ted was extremely painful and dangerous. It’s a part of the anatomy which is meat and drink to germs, and it is a miracle he didn’t die of infection. So why don’t they investigate the many people who had real reasons to want Safra dead?” Churcher went on to say, “Safra was a man with enemies. He earned part of his fortune as a Swiss banker offering numbered accounts reputedly popular with criminals and the C.I.A. Then his Republic Bank of New York collaborated with the F.B.I. to expose the Russian Mafia’s international money-laundering operation.” At the end of the interview, Father Preston said he was considering approaching Lily Safra. “I am thinking of sending her a letter and reminding her of the verse in the Scriptures that says, ‘To those to whom much has been given, much shall be asked.’ It’s a verse that reminds us there is a hell. For Lily Safra’s own sake, as well as Ted Maher’s, I really think that if she knows anything about this case, she should be open about it.”

I have a new book out, called Justice. It’s a compilation of many of my crime and trial stories over the years, all of which were first printed in Vanity Fair—the O. J. Simpson trial, the Claus von Bülow trial, the Menendez brothers’ trial, the Skakel case. As a result, I’ve been appearing and plugging away on a round of talk shows—Larry King, Charlie Rose, Chris Matthews, Judith Regan, the Today show—and let me tell you, it’s a heady experience. People stop me on the street and say, “Hey, I saw you on Larry King last night!” What fascinates me is that total strangers still want to discuss O.J. after all these years. They remember specific details of the trial they want me to explain to them. Why did they let him put on the gloves when the latex gloves were underneath? Things like that. And they get riled up all over again. They tell me where they were when they heard the verdict and what happened in their office when it was announced—the same way people my age remember where they were when Pearl Harbor was bombed, or when President Kennedy was assassinated. I end each street conversation by saying, “Listen, he’s having a shitty life.” Then I’m off to the next show.

A couple of weeks ago, I met up with Linda Deutsch, the highly acclaimed Associated Press trial reporter, when she was visiting New York from Los Angeles. Linda is considered the doyenne of the genre. She and I have covered a lot of the same trials over the years and have become friends, although we tend to look at things differently concerning the guilt or innocence of a defendant. She was in daily contact with Harland Braun, Robert Blake’s colorful lawyer, and she said that the trail had grown cold. She had attended the funeral of Blake’s wife at Forest Lawn. “They haven’t got anything on him,” she exclaimed. Could this be another JonBenet Ramsey case, with a wide range of suspicions but no resolutions?

Barry Levin, a very capable and extremely popular defense attorney whom I met in the early 90s during the Menendez trial, when he was working under Leslie Abramson to represent Erik Menendez, had been hired as a member of Robert Blake’s defense team under Harland Braun in the matter of the murder of Blake’s wife, Bonnie, who was shot in the head in Blake’s car outside a restaurant they frequented. Levin was also recently found dead, slumped over the wheel of his car in the Los Angeles National Cemetery with a gunshot wound in his head. Knowing he was suffering from an incurable disease, he had shot himself. Among the many mourners at his funeral was Robert Blake.

The Blake story has brought forth an interesting anecdote from Phil Stern, who is 81 and who was a special-coverage photographer when In Cold Blood was being filmed in Holcomb, Kansas, in the actual house where the murders of the Clutter family had taken place. Blake, in his finest performance, played the killer Perry Smith. The cast and crew, the director Richard Brooks, and Truman Capote, who wrote the book on which the film was based, were all put up at the Wheat Lands Hotel, and a great spirit of humor and friendship, sparked mainly by Capote, grew up among them, as so often happens on location filming. One of the few people who did not live at the motel was Robert Blake, who stayed in another place. One day Stern said to him, “Why aren’t you at the motel? You’re missing some wild stuff.” Blake, who had made a great show of getting into the character he was playing, replied, “Listen, button pusher, next week I murder them in that fucking basement. If I stay at the motel, I may get to meet and even like them. So how the hell would I be able to properly murder them?”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now