Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

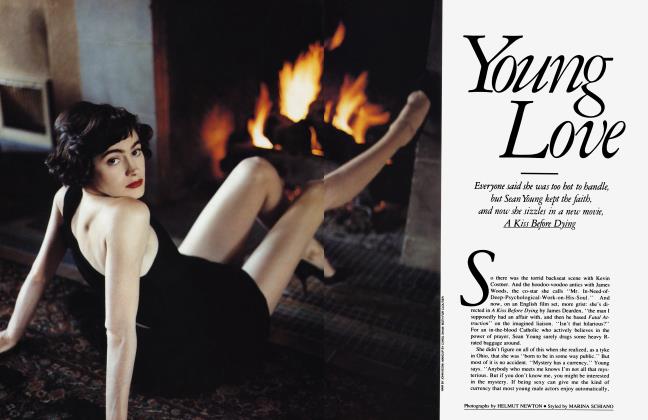

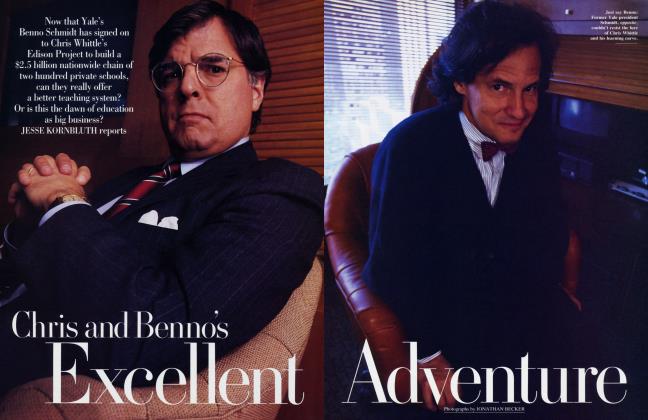

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSCHOOL FOR SCANDAL

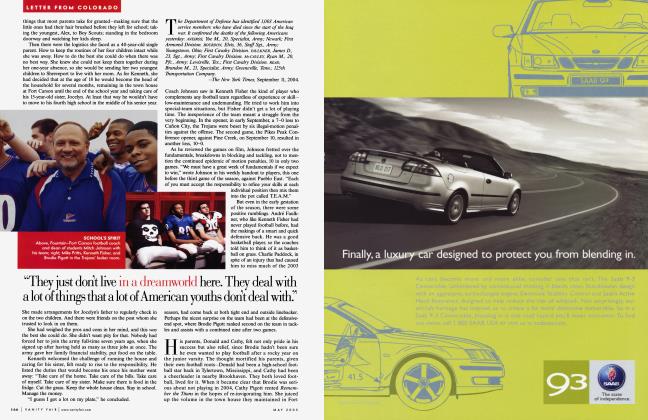

A secret bid to merge the elite all-girl Westlake and all-boy Harvard high schools was more like Barbarians at the Gate than Goodbye, Mr. Chips

JESSE KORNBLUTH

Letter from L.A.

Of course it was madness. Maybe in some backwater, the headmaster of the local prep school raises money for scholarships by bicycling across America. But Westlake is one of a handful of topflight private schools in money-drenched Los Angeles. The campus is a little jewel on a hilltop

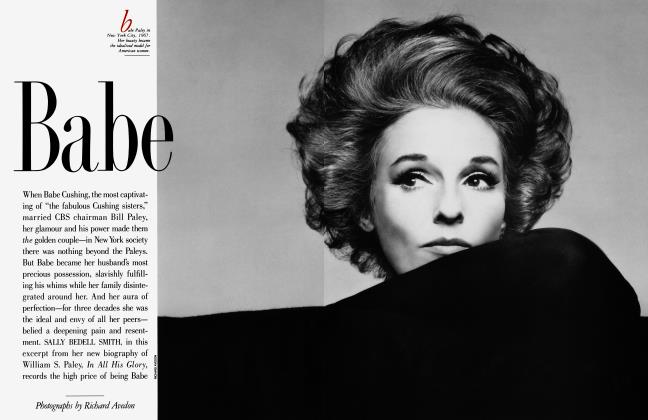

in Holmby Hills, where nobody blinks when Daddy brings the light of his life to school in a white Rolls convertible. Shirley Temple and Candice Bergen went here;

Sally Ride carried her alma mater's banner into orbit aboard the space shuttle; the board of trustees has included people like Aaron Spelling and Samuel Goldwyn Jr.

Given all that, you might expect that Nathan Reynolds would only have to whisper that he was thinking of taking to the highway and everyone would bellow, "Nat, how much do you want?" and he'd pick a booger of a number and they'd sweetly send in their humongous checks—because in the winter of 1989, when Nat Reynolds proposed the 3,150mile bike trip, he had been Westlake's revered headmaster for twentytwo years and was fifty-five years old.

But that s not Westlake.

Possunt quia posse videntur: They can because they think they can. As a motto, that accurately summarizes Westlake. Dreams, empowerment, sisterhood—the ideals of the women's movement were in the blood here long before Betty Friedan went to the mountain and brought down the tablets of feminism. So Westlake's reaction was for Sally Ride to become alumna chairperson of the Cycle for Scholarships, for Aaron Spelling to get Ford to hand over a new van that Reynolds's wife would drive as he pedaled ahead, and for parents and grads to pledge $400,000.

The morning of the launch, an emotional Spelling told the girls they had "the most courageous, the most respected headmaster in this world." With the entire school cheering, Reynolds pedaled down the hill. He not only made it across America in twenty-six days but managed to send a postcard to every Westlake girl and every alumna who wrote a check; on the obligatory videotape, he pedals toward Washington, D.C., to the sound track of Local Hero.

Then the cheering stopped.

On October 3, 1989—just four months after the bike trip, and with no notice to a community that had never heard him preach anything but the gospel of single-sex education—Nat Reynolds walked into an assembly and announced that, in September 1991, Westlake, defiantly nonsectarian and about 50 percent Jewish, would merge with Harvard, an Episcopal all-boys school one canyon and twenty minutes away.

At Harvard, when headmaster Thomas Hudnut delivered the news, boys cheered the birth of a 1,600-student coed powerhouse that would soon be described as "the Exeter of the West." At Westlake, the girls filed into the assembly hall wondering who had died; when they learned it was their school, they raced to the pay phones, weeping, to call home.

Pass over, for now, the trauma dealt to the Westlake students. Consider the parents. These are, in the main, secondgeneration rich people who make deals on a daily basis and who don't like to be kept out of the loop. At a meeting after the announcement, therefore, they were not shy about telling Alan Levy, president of Tishman West real estate and chairman of the Westlake trustees, that

"He's telling Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous to stuff it," one man whispered to his wife as the parents started shrieking.

they wanted the board to postpone its vote. "You are not stockholders," Levy snapped. "You are out of order."

"He's telling Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous to stuff it," one man whispered to his wife as the parents started shrieking at Levy. "They don't know who to call to fix it or where to send the check, and there's going to be blood." Samuel Goldwyn agreed: "This is not the way to go about it. There's going to be an awful fire storm."

What an understatement. That season, Tom Hudnut sadly recalls, Nat Reynolds was "like a fireman in Dresden." Four weeks after the merger announcement, Westlake parents pledged $4 million to keep their school independent, with large contributions coming from Goldwyn and Spelling. "Aaron Spelling was more opposed than anyone, but he didn't want to get involved," says departmentstore heir and veteran Westlake trustee David May II. "Sam Goldwyn called me half a dozen times. 'All I want is a chance to raise money,' he said."

But the board refused to back down. In mid-November, a group of parents sued to block the merger. The board still refused to bend; later that month, the Westlake trustees voted 16 to 5 (with Spelling absent) in favor of the merger. With that, the parents' lawyer—a woman, as luck would have it—asked a Los Angeles judge for a preliminary injunction to block the merger. On December 22, the judge—a woman, as fate would have it—shot the suit down. Later that day the lawyers and trustees triumphantly signed the agreement they believed would officially end all disputes.

Now the merger is moving forward; Nat Reynolds, his friends say, isn't. "He hasn't recovered yet," says one. Neither has the Westlake community. Half a dozen students have been taken out of the school by distraught parents, and Aaron Spelling—who reportedly received an anonymous message urging him to back off if he wanted his son to go to Harvard—is sending the boy to the Brentwood School instead.

It's not that the debate over the merits of singlesex education for young women refuses to die. It's that no one is quite sure if the real issue here ever had anything to do with education. For the Westlake campus sits on eleven prime acres in Betsy Bloomingdale's neighborhood, where a single acre sells for $5 million. In that kind of real-estate market, people inevitably wonder: Is the newly constituted school really going to educate seventh-, eighth-, and ninth-graders on property this desirable? Could Westlake be a tear down?

Good-bye, Mr. Chips. Hello, Chinatown.

Nat Reynolds is tall and lean and tweedy, and on paper, he reads like the quintessential career headmaster. He graduated from the Harvard School, got his B.A. at U.C.L.A., and won a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship for graduate work at Johns Hopkins. He later went back to Harvard to teach English and was chairman of the department by the time he left for Westlake.

Nat and Sallie Reynolds and their three children lived in an apartment at Westlake while Nat did all the right things—ending the Jewish quota, encouraging blacks and Asians to apply, beefing up the scholarship fund. The family spent thirteen years that way, with students around them all day and sometimes in the evening, until Helen Bing, known as Westlake's most caring trustee, decided enough was enough and offered to buy Nat Reynolds a house. "It's more important that the school own a house," Nat said, prodding Bing to put the property in Westlake's name. That was typical of a headmaster who used to return the "contributions" that sometimes accompanied applications to the school from unacceptable girls. Reynolds's early opposition to the women's studies program is less well noted, but once he saw that the girls loved it, he stepped aside and ended up getting the credit for it.

As well he might. For two decades, he had told his students that there is something wonderful and honest and liberating about not having to react to boys at school all day. "It was a very idealistic place," a recent graduate recalls. "We lived in our own reality."

But in 1989 the record of the Reynolds administration was mixed. Westlake was a haven for self-determination where student assemblies occasionally ended with a short prayer: "May God hold you in the palm of Her hand." That was, for those in the know, a fervent prayer—despite the highest tuition of any private school in Los Angeles, Westlake had to borrow from deposits for the next year to pay the spring bills. The endowment was a paltry $500,000.

Two weeks after he announced the bike trip, Reynolds decided the time was finally right for a strategic-planning session to address the school's future. He asked William Ouchi—a professor at the U.C.L.A. Graduate School of Management, author of a best-seller about Japanese business called Theory Z, and a Westlake parent and trustee—to head a planning group. And at the April trustees meeting, he asked everyone present to spend a weekend in July with him in Ojai, a quiet town near Santa Barbara.

At that retreat, twelve of Westlake's twenty-three trustees considered Reynolds's two-hundred-page assessment of the health of the school. He also asked them to consider the future of the Harvard School. He informed them that Harvard had removed some tennis courts, making room for 350 new students. The last time the Harvard trustees had voted on coeducation, Reynolds said, the proposition had lost by only one vote. Tom Hudnut, the new headmaster, had previously run two coed schools. Harvard's future was clear: it could go coed all by itself, and probably would within two or three years. The decision, Reynolds warned, would be made in the fall—just a few months away.

Tom Hudnut taking Harvard coed. Well, it made sense. Hudnut might be gifted as an educator, but that talent paled beside his genius as an executive and self-promoter. The son of a Presbyterian minister, he'd gone to Choate and studied politics at Princeton and diplomatic history at Tufts. He went on to teach English at St. Albans, and very quickly became the school's college adviser, easing himself into Washington's prestigious (and then all-male) Cosmos Club. Hudnut was still an elitist—he rejected the on-campus house Harvard offered his family, preferring to build a social life around L.A.'s business and film communities—but he was too smart to fall into the obvious dead end of traditional snobbery. He understood that the fast track to power in the 1990s was, paradoxically, to champion diversity. For Hudnut, forty-three, taking Harvard coed might be just the beginning.

The Westlake trustees panicked. Every bright girl in town would apply to a coed Harvard. Westlake couldn't go coed on its own—the best students instinctively know there's something fishy about a girls'-school-with-boys.

"For years, Mr. Reynolds told us we were a wonderful group of women. That was the shock-heerased all that self-confidence."

Then magic struck. "I wonder if Westlake and Harvard could merge," mused Helen Bing, the woman who'd bought Westlake a headmaster's house a decade earlier. There was, Bing has recalled, an electric pause. Bill Ouchi suggested that Helen broach the idea to her husband, Dr. Peter Bing, a philanthropist and longtime Harvard trustee.

But then a cloud descended, as everyone remembered how, in 1982, Westlake and Brentwood had considered a merger. Brentwood teachers had found out about those discussions, and their hostility had quickly put an end to the idea.

How to prevent a rerun?

Easy. Don't tell anybody.

And they didn't. Over the next three months, only a couple of the other eleven trustees were told of the plan. As a result, the Westlake planning committee was able to bring the merger to a vote in October without the benefit of any outside advice or criticism. And that was unfortunate, because further investigation would have challenged the most basic of Nat Reynolds's assertions about the need for a hasty merger. Tom Hudnut was clearly more interested in knowing 1,600 families than 800, but he had not—contrary to what Reynolds suggested at the retreat—been hired by Harvard for his skill in taking schools coed. Just the opposite. "When 'the subject' came up," Hudnut recalls, "I told the search committee, 'Only a fool would ride into a single-sex school on the white horse of coeducation.' " Even if the trustees approved the idea, there was not enough space on the campus and no land readily available for expansion. With real-estate prices rising daily, Hudnut guessed that for Harvard to go coed on its own would cost $30 million—unless he was willing to dump four hundred slots for male students to make room for four hundred girls, an act so certain to be unpopular that he never seriously considered it. There was, in other words, no way that Harvard could easily go coed short of a merger.

What about the tennis courts that had been removed? "It was purely for parking," Chris Berrisford, Hudnut's predecessor and Reynolds's friend of twenty years, told me. "We didn't tear the courts out so we could build classrooms. And let me say that I hated to remove those tennis courts. There were cracks in the concrete that helped my game a great deal."

What about the Harvard trustees' meeting that saw coeducation defeated by one vote? "I'm afraid I don't remember it that way," Berrisford continued. "Coeducation was discussed every five years, and each time, the number of supporters went slightly up. We agreed that we wouldn't make the move until there was a sizable majority."

Harvard's expansion intentions, the thinking of its trustees, its timetable for taking the school coed—incredibly, at the fateful gathering in Ojai, Nat Reynolds had been wrong about all of them.

A day or so after the retreat, Helen Bing had another idea: the approach to Harvard should be made through channels. Without saying anything to her husband—"We were functioning as trustees, not as a married couple," she has explained—she called Bill Ouchi, who'd headed the planning committee, and had him meet with Peter Bing directly. From this point on, although Helen was vice-chairperson of the Westlake board, she had only marginal involvement in the merger negotiations.

This isn't to suggest that Helen Bing was far from the consciousness of the merger-makers. "If Helen never gave a dime," says David May, "she was the most important trustee the school ever had." But Helen Bing did give a dime. Each year, with May, she made up Westlake's more than $600,000 annual deficit. In 1986, when the gym and arts center was finished and $1 million was still owed, she and her husband bailed the school out. That fat check came with a string attached—the school was to take on no more external debt. "The Bing agreement," some trustees called it.

By that, they really meant Dr. Peter Bing, who writes the checks that make the whole town sing. "What kind of medicine does he practice?" I asked Hudnut. "Peter Bing doesn't see patients," he chortled. "He practices philanthropy."

And on a fairly grand scale. Generations ago, his family made a fortune in New York real estate. His mother, Anna Bing Arnold, became one of the most beloved benefactors in Los Angeles. Bing has carried on her tradition, but he keeps his name out of the papers and avoids photographers—in the past decade, the only time he stepped out was for Stanford, when he served as a national co-chairman of his alma mater's billion-dollar fund drive.

Most private-school trustees slide off the board and reduce their financial commitment once their children leave, but after her daughter graduated, in 1983, Helen Bing's involvement—and the involvement of her circle—only intensified. Vice-chairperson Daisy Belin and secretary Vera Guerin were her close friends. Sheldon Sloan, the treasurer, had handled the purchase of the headmaster's house and done other legal work for her. Reva Berger Tooley was her traveling companion. Lynne Cohen was her stockbroker. Not to put too fine a point on it, nearly a third of the board was likely to listen with particular attentiveness to any proposal Helen Bing endorsed. The in-group never spoke about their Bing connections, however, and so the other trustees had to learn the hard way that, in what was sometimes called "Helen's school," if you weren't on the A Team, you rode the bench.

I n Japanese corporations, as William I Ouchi explained in Theory Z, deciI sions are often made through the ritual of ringi. A proposal is offered by one executive, who passes it to another for his approval; the second puts his seal on it, passes it to a third, and so on. It is a painfully slow process, but once everyone has signed on, execution can be almost instantaneous. "Individual preferences give way to collective consensus," Ouchi writes approvingly. Unfortunately, this courteous idealist was handed the task of execution without being permitted to first seek wider approval or check Reynolds's information. And so, acting on Reynolds's "facts," he gave away the store.

"The Westlake parents heard that the haven for the liberal, secular Jewish daughter is gone.

Their protector had sold them out."

How many trustees should each school have on the new board? Well, Harvard's endowment was $8 million, sixteen times bigger than Westlake's. "Harvard would not agree to a merger of the two schools unless Harvard had voting control of the board of trustees," Ouchi concluded. (He discounted the fact that Westlake's real estate was worth more than twice as much as Harvard's, because he never contemplated that the new school would sell off the property.) Ouchi agreed that Harvard should have twice as many trustees on the new board as Westlake. But that wasn't all. To get the new, thirty-threemember board down to a more manageable size, a few Westlake trustees would drop off each year. Under this formula, it was entirely possible that in several years' time there would be no representative of the "old" Westlake left.

What role would the Episcopal Church have in the new school? Harvard's bylaws were quite clear: the canons of the church governed the school. In reality, however, the bishop was so removed from Harvard that it was all but impossible to get him on the phone. Ouchi and Peter Bing had no trouble envisioning a "spiritually vibrant, ecumenical school community," with rabbis and women brought in to reflect the diverse religious interests of the students. Given that, they saw no need to tamper with the large cross that looms over the entrance to the Harvard campus.

How would the educational philosophies mesh? Although Harvard fosters competition through incessant multiplechoice testing and its headmaster has been known to announce National Merit Scholarship results—in chapel—as if they were varsity-football scores, its curriculum was pronounced compatible with Westlake's commitment to group learning and women's studies.

Who would be headmaster? Nat Reynolds was emphatic—he didn't want the job. Hudnut would be headmaster, and Reynolds "provost."

In September, with precious few seals on the Westlake ringi, Tom Hudnut and the president of his board met with John Bird, an educational consultant who'd engineered two secondaryschool mergers. "Their concern was: How fast can we merge?" Bird recalls. "They laid out the terms. It wasn't my business to get involved, but I had trouble believing these terms would be seen at Westlake as anything other than giving the advantage to Harvard. They were confident it would go well. They kept coming back to the point that the leadership of Westlake had initiated this."

In late September, Helen Bing's inner circle was dealt its first setback: rumors of the merger were beginning to leak. Clearly, both boards had to meet, not just to be informed of a merger possibility, but to vote. At Harvard, the vote was swift and unanimous in favor of a merger. At Westlake, the majority of trustees present felt more information was needed; a motion was passed expressing merely the "intent" to merge.

The next morning, Tom Hudnut sauntered into a special faculty meeting. ''Harvard is going coed," he announced. The energy shot up. "With Westlake," he added, killing the excitement at the mention of an institution the Harvard faculty considered inferior to its own. Hudnut fared better with the students. They cheered, they roared, the younger boys razzed the juniors and seniors, who wouldn't get to enjoy the anticipated thrills of coeducation.

Back at Westlake, the faculty and students were waiting in the auditorium for Reynolds, who arrived twenty minutes late. He had been up all night; he was exhausted, frazzled, pressured. He spoke briefly: "I have never called an assembly without a reason, and I have never called an assembly where I have ever lied to you, and I am not going to do it now. The original purpose of this assembly was to tell you we voted to merge with Harvard. There's been a glitch. I cannot make that statement now. As soon as I can, I will."

He answered a few questions and then asked the school "to go back about our business." But that was impossible. "For years, Mr. Reynolds told us we were a wonderful group of women, that we could do whatever we wanted, and that was always in our minds because everyone respects him so much," says an editor of the Westlake newspaper. "And that was the shock—the way he erased all that self-confidence."

Reynolds's miscalculation over the students' reaction paled next to his handling of distressed parents. "The board serves at my pleasure," he told one father who questioned the merger. Agitated parents demanded to see the feasibility studies the Westlake trustees had presumably used to reach their decision. They were rebuffed; some concluded that no such materials existed.

In late October, David May, who had handled mergers and acquisitions for twenty years at the May Company, opened a meeting with Nat Reynolds, Helen Bing, Alan Levy, and his daughter and fellow board member, Anita May Rosenstein, by announcing that this transaction had been handled in a shockingly poor fashion. "It's the best and only solution," he said of the merger, "but you've got to tell people the truth: this is a decision based on economics."

According to May, Helen Bing said, "That's kind of crass. Maybe we should have done that, but it doesn't sound right." As May pressed on, an envelope arrived for Bing. "Harvard-Westlake" was printed on it. Inside, beneath a Harvard-Westlake logo, was a recruitment letter, copies of which had already been sent out to the principals of private lower schools.

"My God, how can you do a thing like that? There is no Harvard-Westlake!" David May shouted. "Do we have trustees' liability insurance?" No one knew. They called Karl Samuelian, one of the board's lawyers. "I'm glad you're here, David," Helen Bing said to May. "We should have thought of that. ' ' He stared at her. "Helen, that's kindergarten stuff."

A month later, to avoid voting against his old friends, David May resigned from the Westlake board after twentytwo years as a trustee. Helen Bing offered to throw him a party.

A ddly enough, just as Helen Bing bellgan to talk frankly about economic ics, Nat Reynolds began to be persuaded of the intrinsic superiority of coeducation. Nothing was more likely to inflame the Westlake community than this. "Over the last fifteen years, Nat had let himself become the creature of the parents," says a former colleague. "With the merger, the parents heard that the haven for the liberal, secular Jewish daughter is gone, that the brief moment of believing it might be safe was just another illusion, and that

"There was an awful lot of ball cutting going on around Westlake.

By instituting this radical change, Reynolds told them all to shove it."

the change would bring her under the authority of boys (bad), male teachers of boys (worse), and Episcopalians (worst). Their protector had sold them out."

So they rose up, became Concerned Citizens, handed out "Break the Engagement" buttons, and confronted Reynolds and the trustees at a series of evening meetings. At one, Reynolds said that a form of coeducation had, in fact, already been practiced—the Harvard and Westlake swim teams competed together. A senior, Amy Stephens, challenged him. "I've been on the swim team since eighth grade," she said, "and never competed with Harvard." When her father's turn came, he said, "I just want you to know how proud I am of my daughter for speaking out, because when she came here, she was quiet and shy. And that," Fred Stephens added as the ovation began, "is what the old Westlake did for her."

Why would Reynolds seek to undermine, perhaps even destroy, the unique atmosphere of Westlake? Some who have observed the headmaster over the last two decades say he may simply have longed to finally have his way at something—this "creature of the parents" was tired of being powerless. "I think he pulled this trick as a great Fuck You!" says a former colleague. "There was an awful lot of ball cutting going on around there for a long time. By instituting this radical change, he told them all to shove it—alumnae, present moms, students, feminist faculty."

I n mid-November, a handful of WestI lake parents hired lawyer Karen I Kaplowitz to sue the board; the school engaged Karl Samuelian's law firm along with one other. Harvard engaged Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, and several Harvard trustees brought along their own counsel. Legal bills soared to more than $1 million.

In late November, the Westlake board approved the merger, and the verdict followed swiftly. "The fact that Mrs. Bing is on Westlake's board and Dr. Bing is on Harvard's might be relevant if this were Ford and General Motors," Superior Court Judge Miriam Vogel announced shortly before Christmas, crisply dismissing Kaplowitz's charge of a conflict of interest. "Since there are students of religions other than Episcopal at Harvard, and since they are apparently not troubled by it.. . church domination is not substantial," she added. Then, nailing the coffin shut, Vogel said that whatever ignorance the trustees had suffered when they were first asked to vote was cured by the time the final vote was taken.

It was over.

r was it?

On the Harvard campus, a boy was whistling the rondo of the Beethoven Violin Concerto when I arrived, a sharp rebuke to those who say that Joe Hunt, the kingpin of the Billionaire Boys Club and, by all accounts, a most charming killer, was typical of Harvard students. Inside, Tom Hudnut was eloquent and charming, by turns talking educational theory and suggesting that I call Michael Ovitz at Creative Artists Agency for a reference. When I took him up on that, Ovitz, whose own children are not yet old enough to attend either school, was better than advertised. "I'm crazy about Tom Hudnut," he told me. "The discussions I've had with him—all in social situations—tell me he has a long view for what he thinks is best for children and schools."

That day, the long view meant not telling me that the Harvard teachers are jockeying for power: everyone wants to teach sexy upper-school courses; no one wants to teach at the Westlake campus, where middle-school classes will be held. Nor did Hudnut share a remark he'd made several times to the Harvard faculty: "The people who were against the merger at Westlake have dumb daughters who are going to get eaten up. " Instead, he talked about the unstoppable dynamo the new school will become.

This enthusiasm was nowhere evident at Westlake. The students were resigned; the teachers were grateful not to have to talk about "the M word" all day. It seemed as if a great deal of the school year had been lost, as if a violation had occurred that couldn't be forgotten or forgiven. I tried to keep my conversation with Nat Reynolds on the behind-the-scenes aspects of the merger, but his eyes kept glazing over. "I hate rehashing history," he said at last. "What could I have done to avoid conflict? To speculate is fruitless."

But some still do. They are the alumnae who live in Los Angeles, who have older children or no children and thus don't fear jeopardizing their offspring's educational future by speaking out. A half-dozen of them think they know what it's all about—a plot of land near the Simi Valley that Peter Bing acquired two decades ago. In four years, these people claim, Nat Reynolds will retire and the last Westlake trustee will have departed the new board. Then someone will say, much as Helen Bing did in Ojai, "Hey, why not create a true Exeter of the West?" Then the Westlake campus will be sold to a developer, and the money will be spent on expanding Harvard-Westlake in Los Angeles and carrying out the Bings' grand scheme: to build a boarding school on their fiftyfive acres in Camarillo, forty miles away. Another, perhaps more credible scenario has both campuses being sold and a new day school—with a nice endowment—being built from scratch.

The lawsuit still hasn't been settled, and the plaintiffs still owe their lawyer $235,000, but, short of extraordinary new revelations, Harvard and Westlake are now one. If there is a smoking gun, will the person who has it step forward in time?

Expect no miracles. Expect that some of the Westlake girls, who are so determined to be free and strong, will revert to stereotype and wind up being quiet in class and helping the Harvard boys become leaders. Expect excellence, achievement, reputation. But do not expect God to hold them in the palm of Her hand.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now