Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

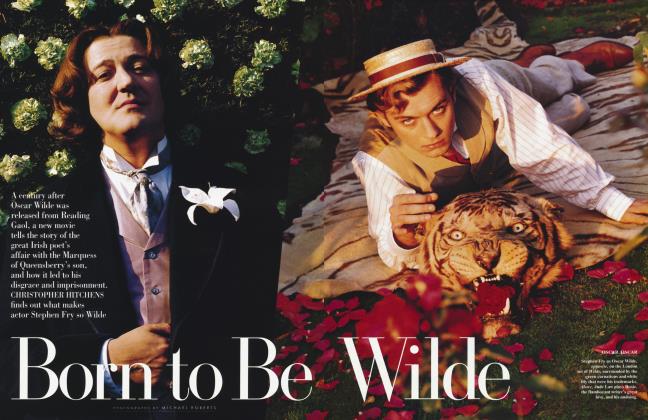

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWith two new acclaimed television series, "Middlemarch" and "Prime Suspect," Americans will see both faces of the British lion: the Queen's sylvan country and the yob's grimy turf

May 1994 Christopher HitchensWith two new acclaimed television series, "Middlemarch" and "Prime Suspect," Americans will see both faces of the British lion: the Queen's sylvan country and the yob's grimy turf

May 1994 Christopher HitchensWhen the British Broadcasting Corporation decides to "do" the 19th century, it decides to do it with the utmost punctiliousness. I was drinking in the verdant scenery of its new production "Middlemarch" when I almost started from my chair. There, as plain as day, was a red squirrel. There haven't been any red squirrels in England since I was a lad. The gray squirrels came—it was always believed that they had somehow been brought with an American circus—and in short order drove all the little russet creatures away. Gray squirrels are mean, street-smart, and wised-up. Folklore held that, when tangling with the red squirrels, they used their larger and stronger back claws to rake and castrate them. Anyway, it wasn't long before the squirrels of my nursery, the pert and sweet squirrels from Beatrix Potter's Tale of Squirrel Nutkin—the ones which never hurt a fly and were an ornament to the woodland—had been chivied and bullied from the glades and spinneys by the predatory gray guys with big shoulders who talked out of the sides of their mouths. Only on the Isle of Wight, where Queen Victoria died and where you can still see a few glimpses of rural England, did the red squirrels survive, protected by a stretch of water from the gray-dominated mainland. In the 50s an obscure novelist wrote a sentimental book entitled The Last Red Squirrel, which used the demise of our neater, sweeter, more refined squirrels as a metaphor for the overwhelming of English culture by mass-produced, violence-oriented Americanization.

Finding some red squirrels for authenticity is just the sort of perfectionist touch, like the loving care expended on costumes, stagecoaches, architecture, and speech patterns, that Americans expect of the BBC. Or, rather, that they expect of Masterpiece Theatre. Tom Wolfe, that great foe of cultural Anglophilia, once observed that the three-M marriage of Mobil and Masterpiece and Mystery! meant that PBS stood not for Public Broadcasting Service but for "Petroleum's British Subsidiary." He mocked the leather armchair, the nostalgia and affectation, the yearning for a touch Theatre presented England as a sort of eternal theme park, populated by deferential servants ("Upstairs, Downstairs") and colonials with calcities upper lips "The Jewel in the Crown"). British Airways and the British Tourist Authority continually minister to the impression this creates, by enticing Americans to come and visit a Beefeater-infested fantasy, complete with. Dickensian fogs and pubs with Dr. Watson propped up in the corner. Indeed, if it weren't for the tourist trade the British might already have gotten rid of their monarchy. Certainly, its role as a magnet for dollar-bearing visitors is one of the prime unofficial justifications for keeping the House of Windsor show on the road.

The gullible American who still makes the trip in search of red-squirrel England is liable to a shock. The gray squirrels are everywhere—football hooligans, feral children, AIDS-ridden derelicts, and hordes of hookers and muggers. "The Yob Society" is the phrase you hear from concerned sociologists and middle-class politicians as they peer into a grimy future. So it was clever of PBS to grab hold of Helen Mirren, as she has led us on a protracted tour of gray-squirrel England in three long and crunchy series of "Prime Suspect," the third of which is to be shown for four weeks beginning on April 28.

Probably nothing was more essential to the red-squirrel image than the old aspect of the British bobby, either the rural constable, pedaling his bike through some idyllic county setting on the way to the vicarage, or the imperturbable cop on a London beat—his amazing unarmed presence a source of reassurance to the solid citizen. Not so with the squad at Detective Inspector Jane Tennison's police station. Here is a world of brimming ashtrays, cheap suits, sweaty armpits, greasy chips, and bad shaves. The denizens are crude racists, sexists, homophobes, shakedown artists, and hardporn fanciers. And that's just the police.

It is a very American world, if you'll pardon my saying so. Not only do the three long narratives feature the modish topics of sexual discrimination, racism, and gaydom, complete with their workplace context, but the whole argot is borrowed from cop serials made in Los Angeles and New York and aired on British TV. London policemen and women are heard discussing "what went down today," and describing people and things as "off the wall," and yelling "Let's go for it." In the new series, Helen Mirren even has a brief affair with an American expert on serial killers, and un-English phrases such as "We have to talk" are uttered. Have things gone so far that people in London are now babbling about their "relationships"?

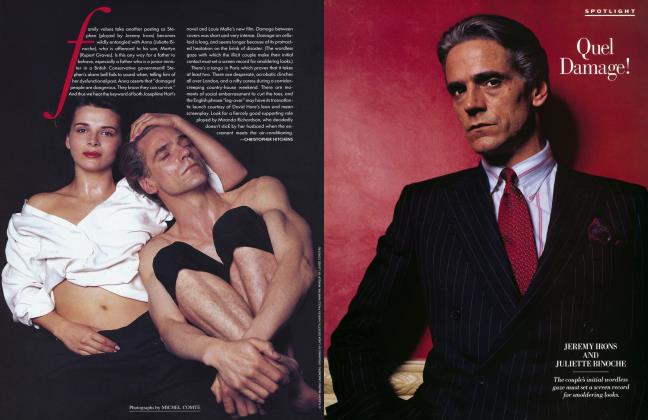

In one respect, though, this is the least American police show you'll ever see. There is no violence, by which I mean that there is much rape, both heterosexual and homosexual, and kidnapping and torture and dismemberment and quite a lot of murder, but in the tradition of the Greek tragedians, it all occurs offstage. There are no car chases; there is no gunplay. Nary a knife is pulled. When a punch is thrown in the second episode, it really is like a blow in the face. Yet the atmosphere of violence and menace is unremitting. This is due to the near-faultless acting of Ms. Mirren, whose performance has an invisible quality to it. You don't notice that she's acting at all, and you can forget (unlike with, say, Debra Winger or Meryl Streep) that you have ever seen her before. I even forgot that I'd seen her romping naked through Caligula, and had to go out and rent it all over again just to remind myself.

The denizens are erode racists, sexists, homophobes, shakedown artists, and hard-pom fanciers. And that's just the police.

"This is the first time I have played a policewoman," says Mirren, "but I wouldn't say it is the first time I have played a character like her. In fact, the character I have played that is closest to her is Lady Macbeth." Tough though that lady's life undoubtedly was, and fast and loose though her attitude toward law and order may have been, she never had to console a policeman who'd been bitten by a male hooker with AIDS, or attend exhumations and autopsies that made strong men lurch and vomit, or have an off-duty affair with a black colleague and tell him very bluntly that he'd better keep his mouth shut about it. Perhaps it helps that Mirren lives in Los Angeles with the director Taylor Hackford, who made An Officer and a Gentleman. It gives her a cultural edge in the mid-Atlantic world of TV, and perhaps also in the fictional setting of "Prime Suspect," where the officers are anything but. Rare is the male superior in this series whose neck is not wider than his head. In one scene, the open secret of Freemasonry within the Metropolitan Police is bluntly mentioned: the unofficial freemasonry of the macho network is the whole theme of the trilogy.

The landscape is unrelievedly bleak. In the first series a lockup garage is used as a psychopath's torture chamber. In the second a backyard in a black slum is found to be a burial ground. And finally, in this new series, a flyblown railway terminal is the preying point for those who devour runaway children. Suspects live in firetrap walk-ups or gritty, windswept housing projects. Abandoned mills and factories, scuzzy seaside trailer parks, sinister amusement arcades—these are the settings. When a badly decomposed corpse is found on a golf course, the brief excursion into the sylvan is almost like—well—a breath of fresh air. And the characters! No English charm here, no teddy bears or foxhounds or witty repartee. The people are surly, cynical, resentful, and greedy, or when they are not (like the West Indian parents of a youth who dies in police custody), they are about to get the shaft. The second-most-memorable face in the new series belongs to David Thewlis, who plays a snarling, whining, crafty pervert—a fixer in Soho's flourishing hustler trade. As with his stellar performance in Mike Leigh's Naked, Thewlis gives us the wised-up, gone-wrong tones of junk Britain.

So, though British products continue to dominate Public Broadcasting's drama schedule, the Anglophile cliches are much less predictable than they used to be. The millions who tuned in to see "House of Cards" last year were watching a drama about the Mother of Parliaments all right—but a drama in which a British prime minister conspires to commit murder. The screenwriter in that instance was Andrew Davies, who also adapted George Eliot's Middlemarch for the BBC, which is to be shown on PBS in six weekly episodes starting on April 10. I had a chat with Davies about contrasting English and American styles.

"Well, I find—though I've never worked for American television—that American made-for-TV movies and American serials are glossy and smoothed-out and bland and simplified. The great exception in my memory was Washington Behind Closed Doors, which I thought was just wonderful and which I daresay had a subliminal influence on the way I did 'House of Cards' and To Play the King.' Sometimes you get a British commercial-TV effort that tries to copy the U.S.-type mini-series or Movie of the Week, but they never quite work."

Do the makers of British serials have the American market in mind when they decide what to make, or how to make it? "I think that perhaps some producers or heads of design departments may be a bit like that, but actually the BBC rather grandly assumes that Americans will be interested in the way we choose to do it. PBS does tend to come along and look at the scripts and things like that at a later stage, but they don't seem to want to interfere."

Though "Middlemarch" does something to restore the image of red-squirrel England, with its lovingly observed dray horses and pewter beer mugs and sheepdogs and stovepipe hats, to say nothing of its jovial, red-faced squires and pale, melancholy curates, the fact is that George Eliot, too, depicts a great deal of squalor and misery. In this highly acclaimed series no less than the book, there are echoes and rumbles of class warfare in the land. Again, the chief agency is that of a strong and intelligent woman, with the signal difference that whereas Detective Inspector Tennison is out for herself, and willing to trample her colleagues to get her own way, Dorothea Brooke is motivated by intense feelings of social and spiritual uplift. (The period, incidentally, is that of Sir Robert Peel, who set up London's first police force. "Peeler," indeed, was an early semi-affectionate folk term for

The Law, surviving into the current century along with "bobby"—which had the same root—and "rozzer," before being replaced in our own fine day by the all-purpose phrase "the filth.")

As a television project, Middlemarch has the huge advantage of having been written as a serial novel for monthly publication. "It's a great help," says Andrew Davies, whose only previous adaptation of Victorian literature was one Dickens short story. "You can see that though George Eliot 'goes longer' with certain individual stories and scenes than we would do, she always gives a good chunk of each theme and each character in every episode—and usually manages a cliff-hanger at the end of each section. So there's no need to contrive too much."

Scenes would begin with open French windows, country-house lawns, and restrained drawing rooms. The words "Anyone for tennis?" could still be heard.

Tough though things are for the cottagers, peasants, and debtors in Middlemarch, the novel is soaked with the atmosphere of impending reform and innovation. Science and industry and medicine are in the process of beginning to revolutionize Middlemarch. What a contrast to the mental and moral atmosphere of "Prime Suspect," where everybody seems to be on the dole or on the fiddle and where income is made chiefly by pornography and prostitution. In order to film "Middlemarch" with any hope of authenticity, the BBC had to scour the length and breadth of the United Kingdom for some landscape that had not been trammeled by highways, electricity towers, Burger Kings, and nuclear-waste dumps. The backdrops of "Prime Suspect" could have been any city in the country.

What, if anything, does this tell us about the continuing hold of British-made programs on American "quality" TV? Part of the answer lies in the literary tradition itself; Dickens and Eliot and Shakespeare are members of the American canon, and likely to survive all attempts at making college reading lists more "relevant" and "exciting." But that in itself doesn't mean that Brits have to make the shows, or put up the money that they famously don't have. So there must be an element of deference in the relationship, combined with an unspoken division of labor. You cast them and write them and produce them, and we'll fall over ourselves to purchase them and praise them. A highly satisfactory arrangement, at any rate from the British point of view, and one that allows them to "have" the cake (of being considered more polished and fastidious) while "eating" it too (Helen Mirren took her immense fee from Bob Guccione's Caligula and used it to buy a hundred-acre wooded retreat in Scotland—not all that far from the ancestral home of Lady Macbeth).

Loamshire, the setting of Middlemarch, was the fictional county ridiculed by the great Kenneth Tynan when he set out on his one-man crusade to reform the English drama He was writing at a time when red-squirreldom was still in vogue, and when scenes would begin with open French windows, country-house lawns, and restrained drawing rooms. The words

"Anyone for tennis?" could still be heard. Tynan wrote that, no matter what the cost in social and theatrical and cinematic "standards," Loamshire must be destroyed. Well, now it has been. Those English fantasias of manners and breeding come from an ethereal region that is as remote from British experience as it once was from the American. The gray squirrels, culturally speaking, completed their hostile takeover. The cleverness of a Helen Mirren is that she's a closet red squirrel, still managing to beat the others at their own game.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now