Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

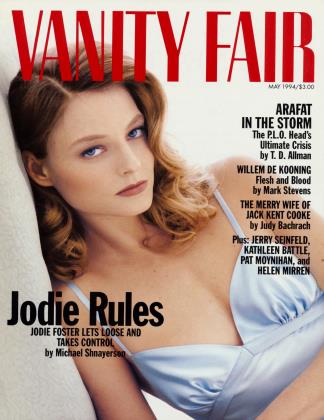

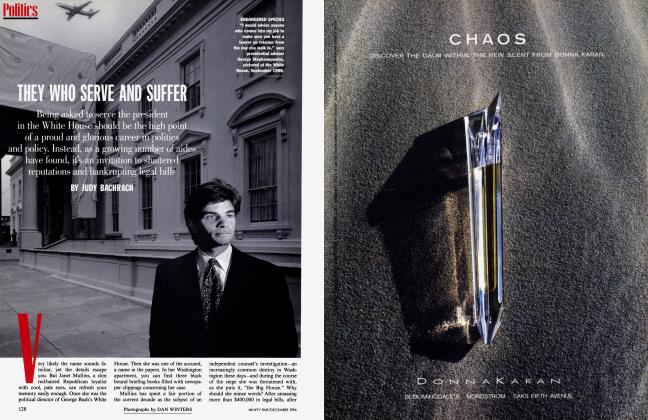

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWashington whispered when Redskins owner Jack Kent Cooke wed Marlene Chalmers, a beauty with a past. Then she was arrested with another man draped across her Jaguar, and the talk grew louder. Now Cooke says the lady is not his wife, but Marlene isn't finished yet. JUDY BACHRACH reports

JUDY BACHRACH

Cooke, the Grief, His Wife, and Her Lovers

Marlene is on the phone, calling from Las Hadas, weeping. The lovely lady, who for a time at least believed herself to be Mrs. Jack Kent Cooke, is in exile from Washington on the beach in Mexico. She has no intention of staying there—if she has her way. But things are so complicated now, more than she can bear. In late December, full of anger and bravado, Marlene fled the capital and her rich old man, taking all the important articles of her life. "My beautiful, beautiful Indian earrings, gold with diamonds and rubies—I had them on when I left." Also accompanying her were her $30,000 Vacheron Constantin watch, her emeralds, her diamonds. Still, she had hoped she might travel unnoticed. But Marlene is rarely unnoticed, and her departure did not fail to rouse attention—from Cooke, the press, and her friends at the Immigration and Naturalization Service. The I.N.S. has, in fact, been following Marlene's adventures rather closely—like all of D.C. A one-woman festival swirling through the streets of the city, Marlene was local legend, the vibrant wife of the big man who owns the Redskins. Even Jack Kent Cooke, a brilliant and powerful businessman, who has conquered the governors of two states, the mayor of Washington, and legions of enemies, is unable to control this charming lady.

"I'm sick and tired. Just wait till I come back—I'll be the most beautiful woman in Washington," she said during one call. But unless the attorney general and the respective heads of the C.I.A. and the I.N.S. beckon, a prospect which seems extremely unlikely, Marlene will probably never be allowed to reside legally in the country that gave her so much: a prison term; youthful male admirers; a wardrobe of braided Chanel jackets that nip her narrow waist; the devotion, however provisional, of the very rich Mr. Cooke (worth an estimated $800 million). No wonder Marlene is crying.

"All this is just a little bit more shit for Jack to dump on me, you know. ... He told me I'd have my green card for Thanksgiving. Then he said I'd get it for my birthday. Now all I'm getting from Jack is the damned dogs!" (One of which—the poodle—is named Chanel.) And Marlene is furious that it is she who must pay the groomers!

Bolivian-born, fiery by nature, the lady has been through some rocky times with her 81-year-old husband. Last fall, their lives took a particularly public turn after her arrest in Georgetown at one A.M. for drunken driving following an evening of Latin music at the Cafe Milano. On the hood of her dark-green Jaguar, police found one Patrick Wermer, a handsome Dutch-born waiter with a very square jaw and a clean brush of hair who is not her nephew, despite the fact that the cops said Marlene had initially claimed kinship. (This happened after she lobbed a gold pump at an officer.) The incident, though perhaps not the start of her troubles with Jack, was at least a downturn in the saga of their mutual enchantment.

By December, the scenario had grown more complex. Marlene had posed for Vanity Fair. Jack was not amused. "He said I've ruined his reputation. He said he's going to show me as a notorious person!" So she left, hoping to teach her husband a lesson by installing herself in a mansion in Mexico, the playground of her most recent ex-husband, Texas oilman David Chalmers, who she devoutly believes is still in love with her.

How rash. How truly Marlene, when you stop to think about it. But now her plans have misfired. Once courted by columnists, envied and lionized by bored Washington hostesses, pampered by servants and shopgirls, Marlene today is besieged only by the good men and women of the I.N.S. who have been reviewing her rather complicated history and are suddenly eager to ensure that her absence from the U.S. is a permanent one. The matter seems more pressing to them since Jack Kent Cooke's stunning announcement in February: "We're not legally married and never have been," Cooke declared.

The announcement, which came just five weeks after Marlene stomped out of his Middleburg, Virginia, mansion, shocked Washington. But not Marlene, who has told friends repeatedly that she had always spurned her husband's amorous advances. Jack had warned her around Christmastime in 1992 that if she left him he had ammunition as potent as anything she could devise. "When I said I am leaving him, that's when he gives me a letter: we're not legally married," Marlene recalls. Her divorce from her previous husband, explained Jack through lawyers, was "falsely obtained." After she left, the old man's pique was increased by the absence of the jewels he had bestowed on her during their three and a half years together. A million dollars' worth. Jack told a friend he wanted Marlene prosecuted. He was wild.

"Is that how much jewelry he gave me?" Marlene says, sniffling some more. "When you get a Christmas or a birthday present, do you give them back?" Naturally not. "Of course I have the cards that came with the jewels." She quotes: "For the most beautiful girl in the world." Later she adds, "When you're small, you get a doll. When you're bigger, you get jewelry. I like to show my jewelry to my friends, to my mother. I like to show my good intentions."

Marlene's sometime lawyer and occasional confidant, Juan Chardiet, explains it all like this: Jack Kent Cooke, he says, has known for "at least" a year that his marriage to Marlene, the fourth and most beautiful of the Mrs.

Cookes, was not legally binding. Allegedly, Marlene's divorce from Chalmers was invalidly obtained in the Dominican Republic on August 4, 1986.

On that date, Marlene Chalmers, as it happened, was doing kitchen duty in the federal penitentiary in Alderson, West Virginia, where she had been sent up on drug charges. Though the exact circumstances surrounding Marlene's alleged divorce remain murky, Chardiet claims that to get a divorce in the Dominican Republic one party must establish residency. Because of her confinement, Marlene was in no position to claim this residency. Chalmers was also elsewhere. Hence, Marlene and David Chalmers are still married, and Jack Kent Cooke may never have to pay a dime on his prenup with Marlene, a contract which she estimates might, in more legitimate circumstances, have netted her $10 million.

"When you're small, you get a doll," says Marlene. "When you're bigger, you get jewelry. I like to show my jewelry. I like to show my good intentions."

"It was Mr. Cooke, through his attorneys, who prompted the Santo Domingan court to void the divorce judgment," says Chardiet. "I know Jack, he's a very nice guy. . . . And I've known Marlene for over 10 years, and I'd characterize her as a volcano. And a volcano you can't tame. You just hope if it does explode it's not a Mount Saint Helens—you hope it's a bit of ash."

"What's the end of this story?" I ask, curious.

"If the immigration matter is not followed up on," he replies, "you'll probably see Marlene on the French Riviera." Then he tells me that Marlene's immigration lawyer, who hoped, in the days when she was Mrs. Cooke, to get her a green card despite her drug conviction, is withdrawing as her counsel.

So at 81, Jack Kent Cooke has proved again that he isn't known as "the billionaire bully" for nothing. But it is the utter casualness with which Juan dismisses the fate of Marlene, his beautiful buddy, that provokes a surprising reaction in me: sympathy. Of all the emotions, it is the last I ever expected to feel for Marlene. It was certainly the farthest thing from my mind when I first saw her a few months ago.

Lovely as the dusk, Marlene Cooke glides into Washington's Four Seasons Hotel wearing her signature white wool Chanel jacket, her right breast burning with a floral spray of diamonds. Blushes have been applied with great purpose; her face gleams like a glazed plate. Floorlength black velvet bell-bottoms hug a tummy gently streamlined into obscurity by plastic surgery a few years before her May 1990 wedding to Cooke—one of the most powerful men in the country and, some say, one of the most detested. At least these days.

Washington's animosity toward Cooke has increased since late last year, when he announced the imminent departure of the habitually defeated but deeply beloved Redskin football team. The news followed months of negotiations; the city of Washington had even agreed to allow Cooke to build his dream: a new stadium bearing his name. But, as sometimes happens with Cooke, his patience had vanished. He tired of battling with the city and the Feds, whose environmental studies were threatening to delay the erection of his eponymous edifice.

Complaining of "obstacles being placed in my path, sometimes seemingly capricious ones," Cooke vowed to build his new stadium—a 78,600-seat facility—in unlovely Laurel, Maryland, next to a racecourse.

Marlene, not surprisingly, has seen the plans. She finds them "stunning."

Not everyone is so delighted. Before grudgingly assenting to the Laurel plan, Maryland governor William Donald Schaefer, who feared that no N.F.L. team would ever settle in Baltimore, initially made no secret of his distaste for Cooke's efforts to build in Laurel. The quarrel between the two was termed "Grumpy Old Men II" by local legislators. Other Maryland officials worry that the cost of preparing the Laurel site could far exceed the $36 million estimated by Cooke. And local residents, already anticipating more noise, more traffic, more trash, are worried that they may be asked to absorb the balance.

Former secretary of the army Cliff Alexander, who once represented Washington in its negotiations with Cooke, does not recall the experience with fondness. He says that the city hasn't ruled out the possibility of a lawsuit against the multimillionaire and then spews awhile: "First time that guy called me Clifford, I called him Jack. The goddamned son of a bitch ain't my father."

Marlene, otherwise occupied, remained aloof from the Redskin drama. But she is aware of Jack's reputation. "Once Jack hates you, you're a dead man. He just doesn't like anyone very much," she tells friends.

In Washington, power is only occasionally tied to wealth; you can be rich and yet ignored, middle-class and president. But Jack Kent Cooke has cash, clout, and the means to entertain the mighty. This combination has given him unprecedented visibility in the capital, where elections bring constant cast changes and outrageous shifts in the pecking order. Rising above the flux, the enduring Cooke has retained up until recently his aura of invincibility. Many heads bow to him. So fearsome does he remain that journalists, business contacts, and dear friends live in fear of offending. His marriage to Marlene, surprisingly, didn't hurt his reputation, despite the fact that she'd done time and he and everyone else in Washington knew it. The glamorous Latin in sunglasses, long gloves, and wide-brimmed hats endowed her husband with just what he needed: the impression of strength and virility. Curled beside him in their private box at the Redskins' current home, R.F.K. Memorial Stadium, her long graceful neck bowed over the stat sheets, Marlene preened like a proud condesa at a bullfight.

"I've known Marlene for over 10 years, and I'd characterize her as a volcano. And a volcano you can't tame."

Juan Chardiet swears that four years ago, when Cooke married Marlene, "he was very much in love with her." And Jack's love carried power. It's amazing, in fact, just how docile the Immigration and Naturalization Service (which has wanted to deport Marlene since her exit from Alderson) became once Jack's attorneys got going. "She's apparently departed and returned to the United States eight times in the years since she's been ordered deported," declares one government source. Persons under threat of deportation normally have no right to return to the U.S. after they leave the country; they in effect deport themselves if they risk a trip outside American borders. Not Marlene. Until December.

"Before this time, I could leave the country and do as I pleased," she has boasted. Some morose government officials thought such exceptional treatment of a felon an outrage. It certainly did not go without remark. Indeed, it has become customary for one wellknown Washington immigration attorney to close letters to the I.N.S. with "I hope you will extend to my client the same treatment you extended to Mrs. Cooke."

"In the 1990s on her way back from Mexico to Dulles airport, an I.N.S. inspector—a real ball-buster—comes on the plane and questions Marlene," recalls one government source. "And Jack says, 'This woman is exquisitely authorized to enter the United States!' And she gets in."

More than that. Just this past winter, U.S. Attorney Helen Fahey of the Eastern District of Virginia signed a 21-page report strongly backing Marlene's application for a green card. According to government sources, "the reason the U.S. Attorney's Office gave for this was that Marlene was this national treasure: she had given up [one of her old lovers] and about 30 people after her own arrest," reports one official. (Fahey herself refuses to comment on the matter, but this is clearly a subject of mortification to the U.S. government.)

(Continued on page 156)

(Continued from page 154)

Why did Jack extend himself so forcefully for Marlene? "Jack has always lived on the edge," recalls a family intimate. Now in his last years, with his health looking uncertain (he has a heart condition), Jack Kent Cooke is living in midair. It is definitely the winter of the patriarch: the Redskins have just finished their worst season in 30 years. And the saga of Marlene may yet become a tale of royal comeuppance. There is a king, a queen, a lot of jousting, a few jesters. There is a lady-in-waiting of sorts, one Suzanne Martin Cooke, Jack's third wife, who paid for Marlene's tummy tuck.

It is Suzanne who summed the story up best. "I believe Jack has met his match," she used to say with inexpressible bitterness of her ex-husband's most recent coupling. "They are perfect for each other."

Marlene/Marlena/Marlen Ramallo Miguens/Chalmers/Cooke is a woman of immense charm and volatility. She is not easily contained. Even prison failed to diminish her natural buoyancy. Her three-and-a-half-month incarceration in Alderson in 1986 on charges of conspiring to import cocaine is recalled as one might an extended sojourn at Eugenieles-Bains.

"This prison, it was like a country club," Marlene once said. "I tell you, no wonder people here continue to commit such crimes. There was a health club, there was great food. There were salads, if you like salads. There was your own bedroom. It was a good rest. I gained weight."

Memories of another arrest, in 1988, for writing bad checks (to a cosmetics store, where she had stocked up on, of all things, Opium perfume), have also been practically erased. All charges against her were in fact dropped, since, the government claimed, she had proved so helpful to the cause of justice.

Indeed, government sources claim, that is the line Marlene's attorneys (paid for by Jack) used to take while furiously fighting her deportation order: Maybe Marlene had a shady past, went the argument, but the "national treasure" more than made up for it. She had informed on the bad guys of the cocaine world, a group that included another discarded husband (common-law), one Angel Miguens. She deserved a green card.

Which makes Marlene's fond reminiscences to friends a little puzzling. "I really didn't know any bad guys," she used to say before her trip to Mexico. "The government could have asked for my help. But they didn't because I couldn't have helped them anyway. . . . They used me only one time to testify."

Legal aid and support were but a small part of the advantages of being Mrs. Cooke. There were the aforementioned purchases at the Chanel Boutique. There was the dark-green Jaguar. There were the thick gold bands tipped with snake heads slipped over her slender wrists. Marlene, however, was not always grateful. On two occasions, she gathered up her latest jewels and, in a fit of pique, flung them at the old man. Usually, however, the gems were not airborne. At the Four Seasons Hotel on the day we first met, Marlene's prettily shaped hands glowed with liquid solitaires: pear-shaped on the left, rectangular on the right. Jack, who until his most recent marriage was not known for his generosity, gave Marlene a canary diamond for her last birthday, an emerald one Christmas. It was the kind of largesse he seems not to have practiced in half a century, when he was still married to his first wife.

"It must be wonderful to be able to dress so casual," said Marlene, sizing me up at the Four Seasons. As I had just spent two hours in earnest deliberations with my closet and mascara wands, I felt this to be a bit harsh. "And no makeup on you," marveled Marlene. "I could never get away with this." Peering closer, I saw her point. Crowning the smooth dark forehead was a guerrilla gang of tiny pimples.

"Stress," Marlene used to say. "All these things jus' keep happening to me."

All these things. Even Marlene finds them difficult to explain. Take the autumn joyride in Georgetown with Patrick Wermer of the square jaw. Following Marlene's arrest, observers hoping to catch a glimpse of Mrs. Cooke's handsome young man stumbled across another of Mrs. Cooke's hunky admirers. "Blond hair, blue eyes, five feet six inches," reports one informed source. "The man was named Serguei. He was Russian, in his 30s. And all around his place are these photos of him and Marlene. And notes too: 'I love Marlene. Marlene loves me.' Like that."

In another notable incident, Marlene was shot in the finger (accidentally, she says) when a gun owned by her husband went off in her hand. More publicity; more sputtering from Jack, who, at this point, started to demand a more domestic agenda for his wife. Marlene, immune to the charms of bucolic Virginia, began to feel she was living a wholly different sort of confinement from that of Alderson, and she itched to escape. She, who used to rendezvous in Rio with drug dealers during Carnaval, claims that she was not permitted to make so much as a glass of orange juice in the Middleburg house, which looks, as a former visitor describes it, "like a spaceship about to take off." Cooke wanted to all but abandon his new house in Washington and retire to Middleburg, where the silver is Georgian, the beds are electric, and the horses, Tennessee walkers, graze on 641 acres. But, for all its privacy, there was no peace at Middleburg for Marlene.

She confided to friends that Jack taunted her for being a felon and a criminal. He told her, or so she said, not to go back to the Cafe Milano.

"And the next day it's always: 'Oh, Marlene, I love you so much, you are so beautiful, I forgive you everything!' And I think, For what? Jack knew my history the first day we met."

Washington is crammed with women who nip to work in jogging shoes. Naturally Marlene hated it. "I guess I'm payin' for being good-looking," she likes to say. Four years ago, on her wedding day, she was more secure, confident in her belief that she was marrying a fortress, great concrete blocks of invincible money. Yet to emphasize how little thought she put into the marriage proceedings, Marlene offers pointed evidence: "I got my wedding dress at Nordstrom."

In public, the often irascible Cooke was, for a while at least, amazingly supportive of his headline-plagued fourth wife. Following the Jaguar incident, he supplied, unasked, the Palm restaurant with a photograph of Marlene to go alongside his own and insisted on its prominent placement. In October, on the occasion of his 81st birthday, with Marlene perched by his side, Cooke deliberately expressed a grand passion for her in front of pal Tandy Dickinson over lunch at Duke Zeibert's.

Duke's is a restaurant of robust food, robust men, and robust backslaps from lobbyists, politicians, Robert Strauss, Sam Donaldson, David Brinkley—anyone in Washington eager to be seen. On entering, the diner is immediately confronted by three dazzling silver Redskin Super Bowl trophies. The team owner commands the star front table—on those days when broadcaster Larry King doesn't get to it first. So it was a fairly public setting for this birthday avowal from Jack to his friends: "Marlene's the love of my life. Of all my wives I love her the most and always will till the day I die."

But Marlene believes that he wanted to keep her on a leash: Why else, she asks, would he have ordered the architect of the Middleburg residence to add on a new gym for her? Why else the new addition for her younger son, Alex, who reminded Cooke so much of himself as a boy? Why did he tell her to redecorate in white fabrics and Oriental wallpapers around his prized Bonnard if not to keep her nimble hands safely occupied? Why else did he deny her the shopping trips all over the country that David Chalmers had allowed her to take? Her indiscretions, she told Cooke, are her problems, in any case. She can hold her own. "No, they're not your problems," replied Cooke, "because you have my name."

But it was a name, as Jack seems to have known by this point, that he could revoke at any time.

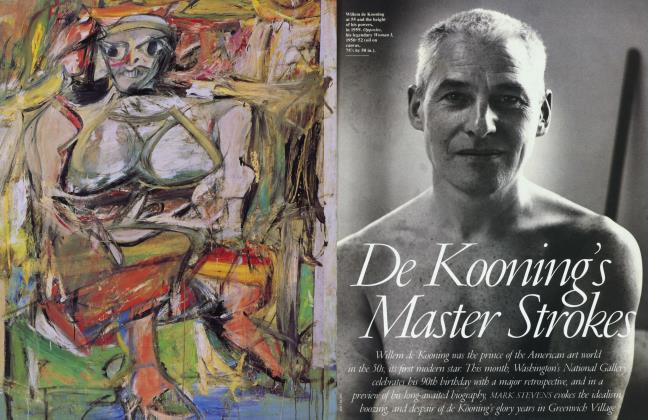

Next to being president of the United States, the most envied position in Washington is owner of the Redskins. "It's like Jack owns Washington," Marlene likes to say—with some accuracy. It is impossible for rational out-of-towners to grasp the unsettling degree of passion that Mr. Cooke's players can provoke even in a bad season. Two summers ago, when Jack got antsy and it looked as if the team were leaving for Virginia, the most mild-mannered citizens clamored for the removal of Mayor Sharon Pratt Kelly (whose political prospects look so dim right now that former mayor Marion Barry, a man who did more hard time for drugs than Marlene Cooke, could replace her in the next election). In a city of staggering racial venom, the Skins have emerged as a symbol of unity. Divorce settlements have been held up because of disputes over custody of Redskin season tickets; the names of more than 42,000 locals are inscribed on a waiting list for season tickets they don't have a prayer of getting in the near future.

Even more to the point, being Redskins owner means being King of the Box, sole arbiter of the power seating above the 50-yard line at R.F.K. stadium, where the famous sip good wine. For almost 15 years this coveted honor belonged to Washington's legendary superlawyer Edward Bennett Williams, who actually owned only a minority share of the team. But Williams ran things during the years, pre-Marlene, when Cooke lived in California.

Fairly soon after Jack Kent Cooke moved to Washington in 1979 he made sure to rip The Box away from the control of Williams, who was not only his friend and business partner but also his attorney, the man who had helped him through his first difficult divorce. After Williams got the boot, Art Buchwald and Sargent Shriver, Ben Bradlee and Joe Califano, Ethel Kennedy and her tribe of children, largely vanished from The Box. In their stead, Cooke enthroned Larry King, the broadcaster; Larry L. King, the playwright; Lesley Stahl of CBS; Stahl's husband, Aaron Latham; the columnists Carl Rowan and George Will; and former presidential candidates Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern.

"You gotta look at the front row of The Box—that's very important. Larry L. King, McGovern, McCarthy—they're not front-row guys," explains broadcaster Larry King. "Now, I've been out in front with George Will and Dan Quayle, special invited guys. I'm usually six, seven down from Jack. I'm told that's sort of status."

It is not, however, a status conferred out of friendship. King, who once referred to Cooke as "a horse's ass," still recalls the team owner's early behavior. "First time I met him I thought he was boorish," he now says with admirable blandness. "Jack and I have never gone out to dinner together. But he grew on me. I got to like him a lot. Jack's an acquaintance. You know, I've heard it said he doesn't have any close friends."

King thinks a bit. He was an old friend of the discarded Edward Bennett Williams and admits without a moment's hesitation that "I would not have been friendly with Jack Kent Cooke today if Edward Bennett Williams were still alive."

Williams died of cancer, after seven brutal operations, on August 13, 1988. A few months before his death, he had received a notification from Cooke's Redskins that he would no longer be getting his postseason tickets.

"He knew he was dying. That's what made some of us so pissed off. It bothered him," says someone very familiar with the circumstances. "I said, 'Ed, this is outrageous.' He said, 'I'm not going to sink to the level of battling with Jack Kent Cooke over football tickets at this stage of my life.' He felt it was undignified, undecorous."

At Williams's funeral, a massive affair at St. Matthew's, only one mourner among the 2,000—Bobby Mitchell—was a Redskin employee.

"For the record, all I'm prepared to say is that Ed Williams and Jack Kent Cooke had a solid and productive working relationship that certainly changed dramatically after Jack came to live in Washington," says Larry Lucchino, former president of the Baltimore Orioles. "Ed chose not to make a public matter of this, and I believe I should respect his wishes." His voice is shaking with an old anger and grief for his dead friend.

Two years before Williams's death, a young woman went to him claiming she had undergone two abortions because of Jack Kent Cooke. Ed Williams suggested that the woman, Suzanne Martin, sue Cooke for $2 million, $1 million for each abortion. "I want to flush that piece of shit out of this city once and for all" is how Williams put it. Instead, the woman became the third Mrs. Jack Kent Cooke, and Williams, like most of Cooke's many enemies throughout his long life, was thwarted in his dearest wish.

Jack Kent Cooke was a 35-year-old Canadian when he entered publishing by buying the magazine Liberty. Earlier, he had owned Canadian radio stations with media magnate Roy Thomson, his mentor. Already he was a brash millionaire. Nothing was ever handed to him except for the incredible luck of being born handsome and exceptionally clever. Age has hardly diminished his genetic endowment. To this day, he has a finely molded jaw and a defiant masculine stare that make observers forget his relatively diminutive physical stature.

"Prison was like a country club," says Marlene. "No wonder people here continue to commit such crimes."

Cooke started life as modestly as possible in Hamilton, Ontario, the first child of a picture-frame salesman and a mother "who was in love with her son," according to a family intimate. "Her name was Nancy Jacobs and her family originated in Poland—they were Polish Jews—and they moved to South Africa. That is the word in the family. His father, Ralph Cooke, came from Australia, met Nancy when she was 16 or so, and they married and went to England and then Montreal before ending up in Hamilton.

"Nancy was overwhelmed by her son; he was the absolute reason for her being. Nothing made her happy unless she had her son's full attention. And she was abrasive, difficult, and small-minded." But there is no doubt that Nancy exerted the most profound influence on the boy. All Jack Kent Cooke's third wife had to do, when angry with her husband, was mention his mother's name and how disappointed she would have been in him. On one occasion, in fact, this tactic reduced the rich man to tears.

On one recent Christmas, Jack Kent Cooke's grandchildren were presented with impressive dark volumes entitled Genealogy of Jack Kent Cooke, the fruit of lengthy research into the Cooke tree, bound, as each book boasts, in "top-grain cowhide," embossed in gold, and prepared by the Family History Department of the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-day Saints. Only the Cooke name and its branches are plumbed; the Mormons came up with solicitors, woolen-mi 11 owners, and drapers as antecedents.

"Jack never told me his mother was Jewish," Marlene tells friends. "His mother was born in Johannesburg. He got this book with his biological tree and everything. And there's no way he's Jewish. He said, in fact, his mother—he thought— was born in South Africa. But no, she's from England."

Nancy herself might not have minded the slight: she had married a devout Anglican, never broadcast her past, and wrapped her eldest in the prickly blanket of her unrelenting attention. Jack, in turn, formed a band and, before he quit high school, tacked on the name Kent, which no one in the family had thought to give him. He became, briefly, bandleader Oley Kent. From this slender perch he pursued and won Jean Carnegie, a quiet teenager.

"They were married when she was 17," says the family intimate. "Her mother didn't think the relationship a good one and they eloped. Her father was a greatgrandnephew of Andrew Carnegie. But she had great style, a charming, beautiful woman, very special—all of the things a man likes to see in a wife."

How happy Jean Cooke was is not open to question. In the course of the marriage she attempted suicide four times. Cooke was making money—lots of it, having bulldozed his way past the tiny radio stations of frontier Canada into, at one time or another, the ownership of the Toronto Maple Leafs baseball franchise, huge chunks of Teleprompter cable TV, the Los Angeles Kings hockey team, the Lakers, and, of course, the Redskins, which he has called "the greatest hobby a man could have." When the couple moved from Toronto to California, their Bel-Air house was painted the color of a Shirley Temple, and was tended by a houseman. Jean drove an Aston Martin and wore a valiant smile, always. Some years earlier, however, her husband had launched an affair with the singer Kay Starr, one of the worst-kept secrets of the day. He was, as former Toronto columnist Alex Barris put it to me recently, "not exactly a monk."

"We are the two unhappiest women in Toronto," Jeannie Cooke told her friend Margo Reid when she first learned of the affair. Margo, who had just lost a child, understood. "Jeannie was a beautiful girl, a wonderful person," she recalls now, more than 40 years later. "And Jack was charming, charming! But he was running around with Kay Starr."

In 1977, with two grown sons (Ralph and John) and a shaken pride to sustain her, Jean got a divorce. "Jeannie had absolutely wonderful jewels. That's what she had to use to pay her lawyers," remarks the family friend, "because she had no money at all." Judge Joseph A. Wapner (who would later become famous on television's The People's Court) presided at the divorce and boosted Jean's fortune substantially. After rejecting the initial $2 million offer her husband had made through his lawyer, the late Bill Shea of Shea & Gould, she got what was then a record-breaking settlement: for 42 years of marriage, $42 million. The figure made Guinness. Rumor had it that this largesse may have been the result of Wapner's learning that Jack had sent a Bekins moving van to the pink mansion in BelAir and stripped it right down to the last stick of Louis XV. (A court order got the stuff returned.)

Ralph Cooke, who sided with his mother during the divorce, found his relationship with his father affected for years to come. His brother, John, apparently also had problems as a result of his parents' split. "In 1985 or '86, John told me that Jack forbade any contact with his mother, but he did it anyway," reports Bob Pack, a journalist who used to be the team owner's friend.

As for Jean herself, "Jack Kent Cooke told me the greatest regret of his life was his divorce from Mrs. Cooke No. 1," says Pack. Nonetheless, as the divorce proceedings drew to a close, he took up with Las Vegas sculptor Jean Wilson, who became known as Jeannie II. They married in 1980, but the union was short-lived.

Oddly enough, Judge Joseph Wapner himself walks into Cafe Milano while I am interviewing Juan Chardiet, who is impressed. "Whaddaya know! What a coincidence: Judge Wapner! Here in town! Just as we were talking about Jack Kent Cooke's divorces."

Chardiet appears to be perfecting the skill of reading upside down: his eyes hardly stray from my note-taking, which is unfortunate, since I have just written, "Greasy hair, wide-cut gray suit, large gold ring on right hand, Ralph Lauren tie with giant snails crawling up it."

So friendly were Juan and Marlene that it was to Havana-born Juan that Marlene first confided her early, modest hopes in 1988. "Juan, you're not going to believe this! Guess who I'm dating!" Juan could not guess. Marlene showed him pictures of Jack Kent Cooke from his brash Canadian days. "Look! Wasn't he good-looking when he was young?" Cooke was 76 at the time of their courtship. And what did you tell Marlene when she revealed she was dating Jack Kent Cooke? I ask Juan.

"I said to her, 'Hang in there! Play your cards right and be a good girl. You never know what can happen.' ... I never thought he would marry her—I mean, he was just getting through with the last marriage."

"And her immigration problems?" I ask Juan, since in his lawyerly capacity he was involved in these matters.

"They tried to deport Marlene after she got out of jail [in '86]," he says. "The government wanted her outta here. Then they offered her a deal: Help us, they said, get your friends out of the country. But, see, then there was this new change of administration. The judge [on the immigration case] saw Marlene on TV in Jack Kent Cooke's box at the game and says, 'Hey, I ordered that woman deported!' So then the shit hits the fan."

Aside from Cooke and himself, Juan tells me, Marlene was utterly alone in this world. Quite abandoned. Juan discovered this four years ago. "The bottom line is all her little friends . . . they all hid in the woods."

And as I hear these words, I can't help thinking how much Jack and Marlene have in common. A host of former friends, for starters. A stable of discarded spouses. A landscape of burned bridges. I think of what Jack's sometime friend sports columnist Mo Siegel told me when I lunched with him at Duke's: "I've known Jack 35 years and no one can stay close friends with this guy. I've never known anyone who could." I think of what former friend Bob Pack said, after Jack tried to ban him from ever setting foot in R.F.K. Memorial Stadium: "Being a friend of Jack Kent Cooke, you don't know how your friendship will end or why it will end or when it will end. But you do know it will end." And he also added, "You know, Jack is possibly one of the more miserable human beings, but if he asked me to lunch tomorrow, I'd do it. He's that fascinating."

Jack Kent Cooke owns or has owned many things aside from the Washington Redskins: the Chrysler Building, for which he paid $87 million in 1979; more than 1.88 million shares of Teleprompter cable, which he sold in 1981 to Westinghouse Electric for $650 million (earning himself a $70 million profit plus a lucrative multimill ion-dollar consulting contract); the Los Angeles Daily News, for which he paid $176 million in 1985; Elmendorf Farms in Lexington, Kentucky, the oldest Thoroughbred-breeding farm in the country, for which he shelled out more than $43 million; the Los Angeles Lakers, for which he paid $5,175,000, in 1965 the highest price ever paid for an N.B.A. team; and the Los Angeles radio station KXLA, which he bought through his brother for $900,000 in the late 50s. (He lost the station without compensation when it was revealed that Jack was not an American citizen, that his brother Donald—who was a citizen—was a front for the station, and that certain fraudulent practices, such as the falsification of logs, had occurred.) He acquired his American citizenship spectacularly and rapidly in 1960, when Congress passed Private Law 86-486, an act "for the relief of Jack Kent Cooke."

The breathtaking Marlene Ramallo Chalmers came to Cooke just as speedily and spectacularly as his citizenship papers. But first there is the story of Suzanne.

In 1987, for a few disastrous months, the team owner found himself married to Suzanne Martin, a plump 31-year-old blonde who was pregnant by him for the third time. "Jack said they got drunk and started sleeping together," Marlene tells friends. Cooke had been going with Suzanne on and off for two years, and he knew she was trouble, knew she was talking to his old enemy Edward Bennett Williams about a possible lawsuit against him because of the two previous abortions, as well as to a writer, who turned out to be Frank Sinatra biographer Kitty Kelley.

"I got a call from Cooke in '87 when I was still his dear friend," says Pack. "He tells me Suzanne's talking to some writer, whom I knew to be Kitty. I said, 'How could you have gotten involved with Suzanne? Didn't you have her investigated before you got involved?' Jack said, yes, he had had Suzanne investigated.

"I said, 'Well, obviously not well enough.' And Jack agreed: 'You're right,' he said. So Jack married Suzanne because she agreed to have the abortion."

With his Fiancee in seeming concurrence on the issue of the pregnancy, Cooke submitted to a wedding ceremony on July 24, 1987. That night there was a celebratory dinner at the Palm with Mo Siegel ("Jack and I talked about the Redskins," Siegel recollects). In Cooke's engagement book a large A was scrawled by Suzanne's name for July 25.

But his new bride reneged.

She stayed pregnant this time, enraging the groom.

Moreover, her arguments for instant parenthood were not well calculated to lull the fears of an elderly husband. "I said, 'But, Jack, look at Strom Thurmond!' " recalls Suzanne. "My God, I wrote Jack letters when I was pregnant, saying, THIS WILL GIVE YOU A NEW LEASE ON LIFE!"

To no avail. Cooke washed his hands of Suzanne completely, leaving her to face childbirth alone. "I ended up being there with her at the hospital as her labor pains got worse," reports Barbara Harrison, a Washington TV journalist who had interviewed the expectant Suzanne. "I was in the position which a father would normally have been in: I assisted her in labor. ... I felt Suzanne thought our interview was an advantage to her, and she was speaking to her husband through television. She said things like 'I love my husband, he's my mentor, my Svengali!'

"Present at at least one of these interviews was Suzanne's good friend Marlene," adds Harrison, almost as an afterthought. "She was curled up on the couch nearby in Suzanne's Watergate apartment. Marlene was always very concerned as to how her friend would be presented on TV."

Give her her due: Marlene Ramallo, Suzanne Cooke's former best friend, has a knack for manipulating the elements of drama, especially conflict. Take something as basic as a place of birth: Marlene says hers is Rio; the records say Cochabamba, Bolivia; a notarized document found in her possession at the time of her arrest in 1986 said Virginia. Other shifting details: Marlene's age (she claims 37; a notarized document suggests 39; her Bolivian passport says 41) and the exact spelling of her first name (Marlene/Marlena/Marlen). She toys with hard facts and soft figures. For example, Marlene says her father, Roberto Ramallo, owns lumber mills and real estate in South America. Whenever she really needs money, "I can call home and my father would give me the money." But if that were true, she probably wouldn't have listed her assets in 1988 as eight dollars in cash and five dollars in a savings account, and the rest of this narrative would probably never have unfolded.

"We're not legally married and never have been," Jack Kent Cooke declared.

It is assumed that Marlene Ramallo arrived in the United States from her native Bolivia in 1972. By this time she already had one son, Rodrigo, six months old, and one failed marriage.

"I was in high school, the American Institute, a very fine boarding school. ... I was supposed to go to Lausanne, but I got married in Brazil instead and my father wasn't against it. I'll tell you why. I was in favor of the Liberation Army Movement. You've heard of it? I was also sympathetic to Che Guevara. Pooh, I love this man!"

In Washington, Marlene worked at Loews L'Enfant Plaza Hotel as an assistant manager and then as a cocktail waitress. Within a few short years of her arrival, she acquired a lover, one Angel Miguens, who fathered her second son, Alejandro. The couple's Stateside troubles began in 1982, when Miguens, who had first been arrested for suspicion of drug trafficking in 1978 in Venezuela (with Marlene at his side), was arrested and later convicted of cocaine distribution and sent away on a 15-year prison sentence. (He was eventually deported back to Venezuela and is rumored to have been murdered in jail.)

"Miguens sold drugs to my son," reports an unhappy neighbor in Virginia, who discovered his true occupation only after Miguens's arrest. He had told her he was in the bicycle business, exporting bicycle parts to Venezuela. As it happened, he was certainly an exporter.

The neighbor remembers one incident vividly. "Miguens asked me to keep a suitcase of his, as he was being deported. .. . In that suitcase were two bags of cocaine and a small automatic covered with rhinestones."

In an earlier era, Marlene might have been called a gangster's moll. Her tastes in men run toward the dangerous. Or maybe dangerous men just run toward Marlene. For four years after Angel's imprisonment, Marlene and her two young sons shared an apartment at the Watergate at Landmark with Bernardo Zabalaga, a Bolivian-born friend. In court testimony, Zabalaga was to describe Marlene alternately as his employer and his halfsister, but these days Marlene denies any kinship. "We grow up together, Bernardo and I, and people think we look alike. And you know how it is," she likes to say. "Finally they think you're brothers and sister. But Bernardo, he watered the plants and looked after the dogs."

But plant and animal life were not Zabalaga's only interests. Found in his floor safe in Marlene's apartment, according to sworn testimony by a D.E.A. agent, were a semi-automatic weapon (which on one occasion he had pointed at the head of a drug informant), 140 grams of cocaine, drug-packaging materials, triplebeam scales, and plastic bags commonly used for packaging coke. In sworn testimony, Marlene Ramallo, his flatmate, denied any knowledge of these items, except for the gun, to which, she claimed, she had been opposed.

Found in a car used by Zabalaga were photos of him kissing and hugging a skimpily clad Marlene, a Watergate courtesy pass stamped with the name "Julian Ramallo" and entitling him to the use of the swimming pool, as well as $90,000 worth of cocaine in various plastic Baggies. Zabalaga was packed off to the federal pen in Petersburg, Virginia.

In 1986, Marlene herself got arrested, and the full story of her involvement in what became known as the Bacarreza drug gang was unveiled. It seemed she had fallen in with a third drug dealer, Ariel Anaya, described as a lieutenant within the organization of Emilio Bacarreza (since sentenced). Kevin Tamez, an agent with the Drug Enforcement Administration, testified that Marlene and her lover Anaya, "among others, were involved in recruiting American citizens to travel to both Buenos Aires, Argentina, and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, for the purpose of smuggling multi-kilogram quantities of cocaine back into the United States in falsesided Samsonite-type suitcases." These activities resulted in the importation of 51 kilos of cocaine, worth about $20 million wholesale.

Altogether, Marlene made three trips to South America—two to Rio and one to Buenos Aires—to supervise couriers who were smuggling cocaine. In fact, the drug was found in Marlene's luggage when she arrived at Washington National Airport from Rio in February 1986.

For her part, Marlene denies the drugs were hers; denies that Anaya was ever her lover; denies she was in Rio for anything other than Camaval. But none of these ardent denials prevented her from pleading guilty to a reduced charge of conspiracy to import less than a kilogram of cocaine—or from going to jail for four months. Asked why she was allowed to plead guilty to such a relatively minor charge, G. Allen Dale, her attorney at the time, emits a sharp cackle: "She had a good lawyer."

She also had a rich husband who paid the good lawyer. For on April 12, 1985, Marlene Ramallo had married genial Texan David Chalmers, the head of Coral Petroleum. Marlene estimates his net worth at "just $15 million." Chalmers gallantly testified in his wife's behalf at her bail hearing, and despite the fact that bail was denied her (she was assumed to pose a flight risk) it is likely his money and affable respectability helped his wife in sentencing. As did Marlene's other ace in the hole: her unsettling beauty.

To read the old transcripts is to see the whole history of human unfairness, which basically comes down to this: good or evil, guilty or innocent, it's best to be a stunner. A judge and a lawyer remarked on Marlene's amazing appeal and made little jokes about it. It was seen as a powerful lure to trap her old friends.

"The government thought they wanted me to be like a D.E.A. agent," Marlene recalls. "I mean like going to South America. But you can put your life in danger that way. I didn't do it."

At some point, David Chalmers got cold feet about the marriage. "David Chalmers divorced me in the Dominican Republic the day I pled guilty," Marlene tells people, adding that to this day she regrets her guilty plea, for which she got an 18-month sentence (she served about one-fifth of that). "Every lawyer who has ever seen this drug case says I was railroaded. I could have sued the government for what they did to me."

What is known for sure is that in 1986 Marlene occupied herself during her long prison days by working in the penitentiary kitchen. She grew plump. She really needed that tummy tuck when she got out, and all things considered, it was nice of her girlfriend Suzanne Martin to lend her the money to become even prettier.

Marlene and Suzanne had been through a lot together during the exciting 80s. Early on in the decade, they had met at a birthday party and socialized on such notable occasions as the Bachelors and Spinsters Ball at the Sulgrave Club. They knew the intricacies of each other's romantic lives. And they understood each other's vulnerabilities. So close were the two that Marlene was present at the bridal shower thrown for Suzanne on the happy occasion of her marriage to Jack.

'I only had one love in my life," says Marlene, and here she is referring not to Jack Kent Cooke but to a rich, lighthaired, thirtysomething socialite named Chris van Roijen. In addition to hosting his famous Halloween party in Georgetown each year, van Roijen occupies himself with watching over his considerable family fortune. (His family traces its roots to Dutch aristocracy.) Following her release from prison, Marlene became intensely involved with van Roijen for two years, but a friend says that Chris's very proper mother, now deceased, was alarmed by the relationship. Other acquaintances suggest that at some point a South American polo player proved altogether too irresistible to Marlene, and that van Roijen found out. Marlene believes she knows how her old boyfriend got this idea: van Roijen was informed of her infatuation by her friend Suzanne Cooke, a suspicion that Suzanne denies to this day. Despite the denials, Marlene's reaction was vengeance. Of course. "I married Jack to get even with two assholes," Marlene likes to say. "Not for his money. Not for his name. Just revenge."

For Marlene, getting even was literally child's play. Suzanne had problems of her own by this point; Jack Kent Cooke refused to have anything to do with her or her baby, Jacqueline Kent Cooke. (The child would be almost three before he met her.) Marlene called Texas and asked David Chalmers's secretary to please hire her a limousine to take her to Jack Kent Cooke's Middleburg home. Marlene was looking extremely good. Her nose had been fixed following a car accident; her weight was down; her tummy was tucked; her sights were set. As for Jack, he had just gotten over a hideously embarrassing public split and the birth of a child that he didn't want. He was lonely. He wanted her, says Marlene, "for companionship." That was all he would ever get, according to the word around Washington.

"Actually, when Jack met me, a week later he said he was going to marry me," Marlene tells friends. "He got this beautiful diamond ring from Sotheby's." All the two of them, Marlene and Cooke, had to do was bury Jack's former wife.

This proved wonderfully easy. In stressful times, Suzanne had talked for hours and hours to Kitty Kelley, who was interviewing her for a local magazine. Later, by the time Suzanne went to court to request a $15 million cash settlement from Cooke for the support of baby Jacqueline, the transcripts from Kelley's interviews had found their way into the hands of Cooke lawyer Milton Gould, who read aloud salient passages of hitherto unpublished quotations from Suzanne. Some excerpts include: "Well, I want to fuck Jack. Excuse my language. I am a little drunk tonight, but I think that every dog has his day, and I think it is time for Jack to lie down and die." Or, alternatively: "When I get the bastard, I am going to ring him and hang him by his balls. ... I am going to sue him big and our prenuptial agreement is not going to hold up in court."

Another equally potent weapon against Suzanne: the ubiquitous Juan Chardiet testified during support hearings for little Jacqueline that Suzanne got pregnant so that the child would become "her ticket . . . her insurance" to financial gain. To this day Chardiet is only mildly repentant about his role in court: "I was very reluctant to testify, but Jack said, 'I'm telling you this child, on my word, will be taken care of.' So I got subpoenaed, testified, and said that Suzanne set Jack up, because in her little pea brain she thought this was her ticket to financial independence."

But what about the kid? I ask Juan, trying to pull him into the present. Jacqueline has a father who refuses to see her. A little tough on a six-year-old, no?

Believe it or not, Juan can live with the idea. "So he never sees his daughter. It's an insulation. It's cruel and unusual to see someone you know you cannot enjoy for long. It's a tough philosophy, but I understand that. Jack was deeply hurt. He looked at [Suzanne's pregnancy] as a business proposition. He said, 'She's trying to screw me and get my money without my permission!' "

And that's how little Jacqueline Kent Cooke, the very image of Jack, ended up with only $29,000 a year, despite her father's great wealth. The child, living in New York City now, attends private school and receives psychotherapy, which her father refuses to pay for. Suzanne, according to her lawyer, Peter J. Unger, is "living on borrowed money." She has had to hawk her jewelry to defray her daughter's tuition expenses. To get a little more money out of Jack, Unger may apply for relief under the Uniform Support of Dependents Law, a kind of deadbeat-dad law, originally devised to help out indigent spouses and their offspring.

Is this a ploy to shame Jack publicly? I ask Suzanne's lawyer. "No," he sighs mildly, "because, to be perfectly honest, in my opinion Cooke is an old man with a lot of money who doesn't give a damn about anyone but himself."

You know, I came up with that phrase 'billionaire bully' for Cooke," the sleek and handsome lawyer Cliff Alexander tells me, almost shyly. Sharon Pratt Kelly's former negotiator with Cooke is not a bragger, but he's clearly very pleased about this invention because the epithet has stuck. In the only inspired moment of her administration, Mayor Kelly hurled Alexander's alliteration at the team owner in a press conference, and the city cheered. "She was very glad to say it," says Alexander. "I mean, she wanted to say it."

"Cooke's always tried to do things his way with his money"

By the summer of 1992, everyone knew Cooke wanted a bigger stadium (the Redskins have the smallest facility in the National Football League), and to get it he was making all sorts of threats about leaving town. This was not news. What did cause talk was Cooke's patting Mayor Kelly on the fanny. (The mayor huffed privately that he had also called her "my darling girl.") And then! And then! Jack had gone off into the sunset with Virginia governor Doug Wilder and vowed to stick the Redskin team in Alexandria.

"Virginia gave him such a sweetheart deal," snorts Alexander, who was brought in by Kelly to save the day and lure Cooke back to Washington. As it turned out, he didn't have a lot of luring to do. Alexandria didn't want the Redskins.

"See, the problem [with Mr. Cooke]: he just assumed he was with the Redskins, people will let him do anything he wanted," says Mark Moseley, a former Redskin kicker. "But instead of going in and trying to address the individuals who were worried about the stadium, Mr. Cooke just went in and said, 'This is what we're going to do ... ' Well, people got their back up, and Mr. Cooke doesn't understand that at times. He's always tried to do things his way with his money."

So Mayor Kelly's felicitous little phrase caught on. The only problem is that it is less than accurate. Cooke's Chrysler Building, for example, which he actually leases from Cooper Union, has, in the indifferent New York City real-estate market, a reported 24 percent vacancy rate, and in 1991 his New York real estate ran at a $3.1 million loss. His beloved Lexington, Kentucky, horse farm, now run by his son Ralph, has plummeted drastically in value from its $43 million purchase price. His newspaper, the Los Angeles Daily News, which he bought almost a decade ago for $176 million and sank an additional $79 million into, might be worth around $200 million these days. "Cooke has been squeezed, but far from crushed, by the recession" is how The Washington Post summed up his wealth last year.

For all her animosity toward her old friend Suzanne, Marlene has never understood why Jack won't provide a house for his little daughter.

"Jack does not respect women," Marlene tells a friend. "If he respected women, he would pay for a house for Suzanne and the child. I tell him this. He says, 'No, the lawyers will not let me do this.' I say, 'To hell with the lawyers.' But he says, 'No.'" This past Christmas, says Marlene, she bought Jacqueline a "beautiful gold heart with diamonds from Neiman Marcus. It cost $4,000, and it says, 'From your dad, with love. Christmas 1993.'" Marlene recalls that Jack was apprehensive about the bauble. He worried that Suzanne might pawn it. But Marlene shrugged and declared, "At least she'll be able to pay the rent."

Marlene tells people that there's much about Cooke she has never understood. She has often wondered, it seems, why his children and grandchildren never dropped by the house in Middleburg or Marbella, the city house he bought after he married Marlene. "You know, I come from a culture where family is always around," says Marlene. "But Jack's kids, his grandsons, they don't even come for Father's Day. During Christmas, they only come for maybe an hour."

Behind the headlines of Jack's moves, Jack's team, Jack's wives, Jack's kids, lies what seems to be a fairly constant subtheme of perpetual loneliness. (Fitzgerald's Tender Is the Night is one of Cooke's favorite novels.) Marlene has been saying that he is seriously thinking that he wants to have another child. "I say, 'What about the baby, the girl you already have?' He doesn't wanna talk about that."

To see Cooke on television, to hear him speak, is to listen to someone inexpressibly pleased with himself and all his doings. And yet, "about a year and a half ago he comes in here, all alone," says Mel Krupin, a co-owner of a Washington deli, who fell out with Jack long ago. "It was dinnertime. He was alone. We broke bread together. He ate a cornedbeef sandwich, as a matter of fact." Alone in a deli at dinnertime? It is a startling image.

He may not be eating alone for long. From Las Hadas, Marlene told a friend, "The only way to grow old gracefully is by not being married." She may, however, live to change her mind.

In early March, Marlene crept quietly back to the U.S. and Washington and phoned the angry Jack. She told friends that he advised: "If I were you, I'd leave this town tomorrow." A few days later, a bunch of I.N.S. agents had placed her under administrative arrest and she was again facing deportation. While agents waited at her Alexandria condo, Marlene poured out her soul to Jack on the phone. Evidently much moved, he demanded to speak to an I.N.S. agent. But his pleas had no immediate impact.

On March 14, a Chanel-wrapped apparition in spike heels appeared at I.N.S. headquarters in Arlington, Virginia, to plead her case. She was not alone; a coterie of lawyers hovered around her. The lawyers were, as Marlene might say, stunning. The I.N.S. agents, determined to see justice done, brought up the matter of the lady's unauthorized trek to Las Hadas. But to no avail. U.S. Attorney Helen Fahey refused to issue an arrest order for Marlene, who was once again, it seemed, under the protection of an old ally. "I'm falling in love with Jack again," Marlene had confided to a friend the day before. In short order, after posting $50,000 in bail, the lady traded her cramped I.N.S. cell for a speeding limousine, free at least temporarily from those who would attempt to possess her.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now