Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHouse of Altman

Here they are, the A Team of the A-line, the celestial cast of Robert Altman's upcoming film, Prêt à Porter, the movie that should do to couture what Altman's The Player did to Hollywood. But as BARBARA SHULGASSER—who co-wrote the script— reports from the Paris set, when this many stars are on the runway, anything can take off

BARBARA SHULGASSER

In May of 1993, I received a telephone call. "Bobbie? It's Bobby Altman. We're making Pret a Porter. Congratulations. Miramax loved your script." There was a touch of disdain in his voice. "Just shows you how much they know about scripts. I don't mean to insult you, but they don't have much taste."

I could hear him sniff—a characteristic mannerism that comes of clamping his mouth down to suppress unwanted smiles.

"Have you read the script?" I asked hopefully.

"No, I haven't," he said. "We're going to have to rewrite."

"You haven't read it. How do you know it needs to be rewritten?"

He paused meaningfully. "Because I want to make my movie."

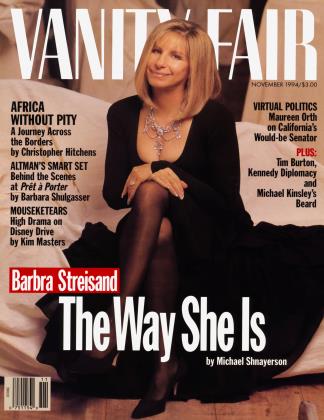

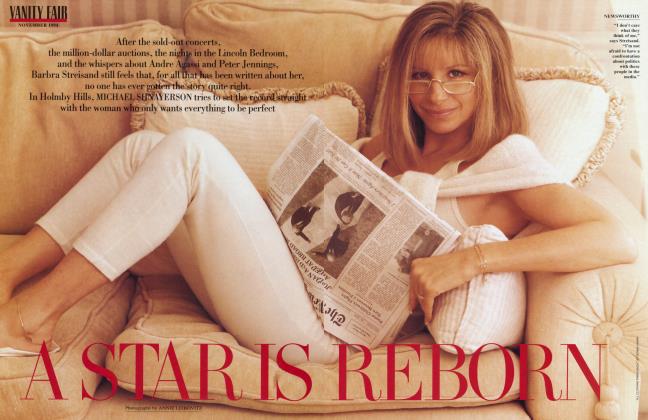

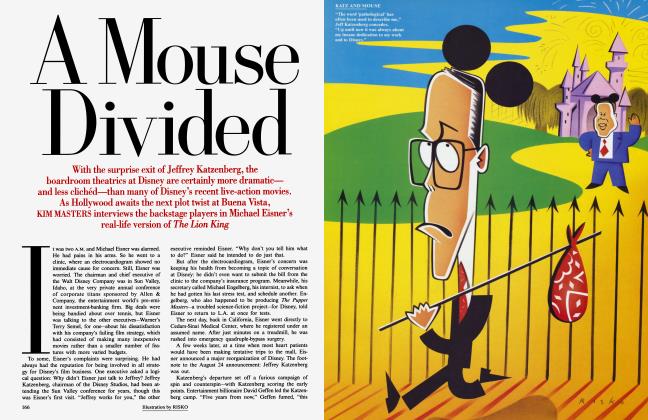

Ten months later, he made his movie, Pret a Porter, a lush, densely populated, logistically chaotic essay on art, love, jealousy, beauty, nudity, greed, and the need to watch where you step when walking in Paris. Pret a Porter ("ready-to-wear" en frangais) is set against the Paris fashion scene and extravagantly cast to include Sophia Loren, Kim Basinger, Anouk Aimee, Marcello Mastroianni, Julia Roberts, Stephen Rea, Tim Robbins, Tracey Ullman, Danny Aiello, Rupert Everett, Richard E. Grant, Linda Hunt, Sally Kellerman, Lauren Bacall, Ute Lemper, and Lili Taylor, with appearances by designers Sonia Rykiel, Jean Paul Gaultier, Thierry Mugler, Christian Lacroix, Vivienne Westwood, and many other fashion types.

Altman had conceived of making the film in the 1980s. Fed up with the Hollywood scene, he was then working in New York. When he visited Paris to promote Streamers, he attended a Sonia Rykiel show and loved its spectacle and drama. Immediately he imagined some characters and situations, and commissioned several writers to turn these sketchy elements into treatments, scenarios, and scripts. But he wasn't happy with any of them. Pages and pages sat in his office in a big blue file folder.

We met in 1990, when Altman came to Mill Valley, California, to promote his van Gogh biography, Vincent and Theo. I interviewed him for the San Francisco Examiner, where I am a film critic. He liked the piece and we began to talk about collaborating. When he said to me, "How would you like to write my Paris fashion movie?," I thought, Is this what directors say to people when the conversation flags? I pretended that it wasn't the best offer I'd ever heard, and casually said, "Sure." He didn't mention it again for another six months.

Soon after, he signed on to make The Player, the film that in 1992 thrust him back into prominence. Suddenly, financing a new movie looked possible, and Altman told me I should start thinking about his fashion script. "You have to work on spec. I can't pay you now," he told me. "But if The Player takes off, I think there'll be some money for this soon."

We flew to Paris to see the March 1992 ready-to-wear shows. We worked on the plane, discarding the main plot and devising a substitute. After 10 days in Paris, I returned home to San Francisco to execute the changes. Altman called me every day. The question was always the same.

"Are you finished yet?"

In May the answer was yes, and I sent the script along. Then I began to call him. The question was always the same.

"Have you read it yet?"

The answer was always the same: "No."

Altman had lost interest in the project. But by that time he had entered into a development deal with Miramax, which would soon be purchased by the wealthy Walt Disney Company and was moving from distribution, in which it has made its name with such films as The Crying Game, into production, an uncertain and in many ways unrelated area. Putting its name on an Altman picture would be an auspicious start.

Contractually Altman owed Miramax a script. So, without reading it, he sent them what I'd written. He seemed sure that that would be the end of it. He forgot to account for Miramax's bad taste.

For months afterward, our telephone conversations began the same way.

When De Niro wanted to return to Pret a Porter Altman said no, he was committed to Whitaker

Mastroianni and Loren often huddled together. After all these years they still seemed to amuse each other.

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

Anne Archers "people" called So did Sigourney Weavers.

Altman: "The project is on."

Me: "Yes, you already told me it's on."

Altman, sniffing: "But it's been off and on six times since the last time we spoke."

The reports of off-ness or on-ness did little to dissuade me from my conviction that the film would never be made. Thousands of screenwriters bang their heads against Los Angeles walls every day, pitching enough high-concept to tear their rotator cuffs, lamenting their nether lives in turnaround hell. How could I be so lucky?

I arrived in Paris to begin rewriting in October of 1993. Altman celebrated the occasion by reading the script—a year and a half after I'd sent it to him. I found him in a good mood.

"The real problem is that we've got this cast of heavy hitters and they all want something to do," he said. "We have to come up with something for each of them. I feel great. I read the script and while I was reading I wasn't in a panic. We're farther along than I thought. Better shape than when I started shooting The Player."

I remember saying to myself, These are all compliments, I think. I was eager to get down to writing.

Altman was eager to avoid it. "Picking the lint off my suit" is what he called his ingenious methods of procrastination. The evasions ranged from taking unimportant telephone calls to playing solitaire; he stayed busy. You could just see him thinking, At least I'm not working.

Not until the actors who had signed on without seeing a word of script began asking to see pages, not until the producers and schedulers and budget-makers were begging for something on paper according to which they could concoct their predictive numbers, did Altman nervously park for hours at a time in a room with me and a PowerBook. He sat at the keyboard—miserable and scared, moaning and sighing—and typed, suffering through every minute of the rewrite.

One of our biggest problems rewriting was trying to keep up with the frequent requests of actors begging to be in the film. In October, Lena Olin stopped in to meet Altman. Anne Archer's "people" called, making inquiries. So did Sigourney Weaver's. Anjelica Huston had been in touch for months.

Robert De Niro mounted an impressive campaign. Altman was reluctant to consider him because most of the casting had been finished by then; there really wasn't an uncast role large enough to make use of De Niro's talent. Misinformed that we were fictionalizing living characters (others in the fashion industry were equally mistaken, assuming that Anouk Aimee was playing Sonia Rykiel, Danny Aiello was playing Bloomingdale's buyer Kal Ruttenstein, and Lauren Bacall was playing Diana Vreeland), De Niro had originally expressed interest in playing Karl Lagerfeld. Actually, Altman had as a courtesy asked Lagerfeld to play himself, but the designer reportedly didn't like the idea of being in a movie of which he wasn't in some sense the director.

Altman found himself seduced by De Niro's unflagging pursuit and also, I think, devilishly delighted by the idea of giving yet another superstar a secondary role in one of his cameothons. With De Niro on board, we rewrote the part of a gay designer originally called Arthur Rader and conceived to be played by someone like Bob Hoskins or Ed Asner.

Arthur Rader was renamed something more Italian—Cy Bianco—and reinvented to suit the actor. At the last moment, Martin Scorsese announced that his film Casino, to which De Niro was already committed, was ready to shoot at the same time as Pret a Porter. De Niro dropped out. Altman immediately turned to a man few people would envision as De Niro's natural alternative, Forest Whitaker. When Scorsese's film was delayed, De Niro wanted to return to Pret. Altman said no, he was committed to Whitaker.

altman on the set was a joy to watch. He usually stuck to the situations mapped out in the script, but something about seeing the dressed set and the costumed actors triggered the release of his creative chemicals. New dialogue erupted out of him. He was like a delirious patient, a speaker in tongues. Here were his characters and suddenly he knew what they would say. Or not say.

In a large Paris apartment in the chic Fifth Arrondissement, Altman was rehearsing a scene in which Sophia Loren, playing a wife who has been unhappily married for almost 40 years (and will soon be widowed), is about to shut her bedroom doors angrily in her husband's face. Jean-Pierre Cassel had the role of her husband, a fashion bureaucrat involved in a long-standing, open affair with the designer played by Aimee. Loren's character's irritation with her husband was compounded by the discovery that her little Maltese had defecated in the hallway.

Loren is tall and remarkably solid. She doesn't smoke. She is said to exercise for 40 minutes every day. She has worked hard to cultivate and nurture what nature gave her, but, mamma mia, she has fabulous genes. She was 59 at the time of the shoot, yet she still gleamed with fruity youthfulness. And though she wore a lot of makeup, it couldn't obscure the delicate, bold shape of her skull, or her magnificently too large nose, or her absurdly wide mouth that is Calling All Men at the same time as it is laughing at them. But never mind her face: she wears strapless dresses! Apart from the gravitydefying engineering that boosts her bosom to impressive heights—who can say whether naturally or technically supported—you notice that the skin of her shoulders gives off a sheen, like the dewy iridescence of a debutante.

Anjeltca Huston had been in touch for months

On the first take, Loren exuberantly slammed the double doors, muttering deprecations in Italian.

"Cut. Very good," Altman said. "Try it without saying anything this time."

Loren made a face of protest. "I'm Italian," she said.

Altman: "You have to say something?"

Loren: "/ would."

Altman: "This has been going on for 40 years. You still have to say something?"

Loren: "I could say more."

Altman, laughing: "No, no, no. Whatever you want, whatever you think."

Before the next scene could be shot, the discussion turned to the crucial placement of the excrement. David Ronan, a set dresser, was in charge of dog droppings.

"Are we ready for the shit, Bob?" he asked. Given the go-ahead, he pointed a pastry decorator at the floor and carefully squeezed out two little curls of special mixture.

Pierre Mignot, one of the two directors of photography on the film, removed his glasses and squinted through his lens. "It's too dark, Boh-buh," said Mignot, a FrenchCanadian, aspirating the nonexistent vowel at the end of Altman's name.

Three propmen appeared, fastidiously scooped up the sample, and cleaned the soiled spot with paper towels. Ronan rushed to a corner, where he performed his alchemy, turning canned dog food into waste without the benefit of an intervening canine digestive system.

Altman stalked the set with his arms held out in front of his rib cage, his thin hands hanging from his wrists as if he'd just rubbed his palms together in delight.

Ronan returned and, kneeling at the targeted spot, extruded another small brown sculpture onto the parquet floor.

Mignot peered through his lens again.

Altman looked to Mignot. "How's the color?"

"Now it's the same color as the floor, Boh-buh."

The experts conferred.

Loren examined the leavings. "Un peu de legumes? Quelque chose verte?" (A few vegetables? Something green?)

Cassel: "A touch of yellow?"

As ever, Altman was half participant, half observer. "All these adult artists standing around discussing the color of merde," he said, then loudly sniffed, fighting back an incipient smile. Everyone around him laughed.

The three set dressers reappeared to clean the floor again. Another faux stool was gently squeezed into place.

Altman: "Yes, good. Pierre?"

Mignot: "Good, Boh-buh."

Altman: "Everyone feel good?"

Cassel: "I feel soooo good."

Directing Pret was an exercise in paring. "You have to overwrite in the beginning," Altman had told me. "When I shoot I may only use two lines, but the actors will need a whole page and a half of dialogue to get themselves in a position to be able to edit out what they don't need. Most of what ends up in the picture you can't anticipate."

Entire scenes would be dropped. New ones would be invented on the spot. One scene was hastily thrown together when the designer Thierry Mugler agreed to dress several models in mirrored bikinis and leather miniskirts in our backstage Louvre space during the real pret-a-porter shows.

Difficulties arose every day. At one point, unable to create a properly sinister situation to exploit Milo O'Brannagan, Stephen Rea's character, we made a copy of the script in another file and asked the computer to remove every reference to O'Brannagan. The script seemed to work fine without him.

"If we can't make this character really terrific, there's no point asking Stephen to play him," Altman said. He rose to pace. He wasn't happy.

"I always get myself into a bind. I cast it, and I have to write something for all the actors. I hate that I got into this fucking business. I wish I could just be sitting around watching football, not a care in the world. I'm panicked. Why did I get myself into this mess?"

"If you weren't in this mess, you'd just be in another one," I said.

"You mean mess is my natural state?"

The question was rhetorical.

The pret-a-porter collections are shown every October and March. Until last March, most of the shows were staged in large tents pitched in the courtyard of the Louvre. We filmed the first shows to be produced in the salles of the Louvre's new underground gallery. On the first day of shooting, the actors were understandably nervous. Never having played their characters before, they were asked to sit in the audiences of the actual fashion shows, behaving as if they were journalists, buyers, and fashion people, without the benefit of lines, lighting, or any real direction. They wore body microphones and were told to improvise, to chat with one another and real people in the audience. They dared to do all this without knowing when or if one of the two cameras might be trained on them.

We had 10 weeks of shooting ahead of us, five to six days a week, 12 to 14 hours a day. Standing before the cast for a pep talk, Altman looked drawn and tired. His beard looked tired. A few years ago, back before Ethan Hawke and other twentysomethings started decorating their chins with wispy growths of hair to prove they'd reached puberty, Altman had been wondering if his goatee wasn't really kind of a silly adornment. For several weeks, he told me, working millimeter by millimeter, he gradually trimmed it down to something that looked like a big white eyebrow stranded at the wrong end of a face. But after 30 years of beard, he confided, "I couldn't shave it off. I'm afraid of my chin."

(Continued on page 200)

(Continued from page 181)

He'd also lost 50 pounds in the previous five months, since finishing Short Cuts. In October, he walked into the Paris production office wearing a Cerruti suit, a heavy, wheat-colored single-breasted work of art that hung stylishly on his newly svelte frame. The trousers were pleated and cuffed and broke grandly over his brown Italian oxfords.

"You know, since you started working on this movie, your wardrobe has improved about 1,000 percent," I said to him.

"Fuck you," he replied.

I plunged insensitively ahead. "I just want to know: when you made M*A *S*H, did you learn about medicine?"

"No," he said, sniffing loudly, "but I learned how to operate."

'Stay in character," he told the actors Othat first day. "If the photographers call you by your real names, don't respond. Don't worry about making a mistake. We'll cut all the mistakes out. We'll make you look good. Just go out and be gutsy. We'll protect you. I don't know what I'm doing, but I trust that you all do."

The actors barely knew their own characters' names, never mind the names of their fellow actors' characters. Sitting backstage waiting for the show to start, they twitched and paced, Thoroughbreds readying for a race.

"Sally is Sissy?" said Stephen Rea to no one in particular.

"Who is Rupert?" someone else asked.

"Milo would know everyone, but he would pretend not to know them," Rea speculated. "Right?"

After the actors had been led into the Christian Lacroix show, I took a seat in the audience a couple of rows behind Basinger, Loren, and Bacall and was blinded by the explosion of flashes from the cameras of a hundred overstimulated photographers, gaga at the high concentration of celebrities per square inch. A photo of Basinger, Bacall, and Loren, sitting together at the Lacroix show? Every magazine in the world would want that one. I put my sunglasses on to protect against the blaze, and instantly berated myself: The filming hasn't begun yet and already I've gone Hollywood.

In a room in the depths of the Louvre, the production had set up costume, hair, and makeup departments. At one end of the space, a coffee urn and too few chairs had been arranged. Here sat Kellerman, Bacall, Tracey Ullman, Linda Hunt, Lyle Lovett, Chiara Mastroianni (Catherine Deneuve and Marcello's daughter), and others, some of whom were accustomed to having trailers as large as the entire room completely to themselves. But then, they were also used to being paid about 20 times their current salaries.

Marcello Mastroianni is now 71 years old. The Fellini alter ego in La Dolce Vita and 8/2 is, if anything, a more masterly actor today than he was 30 years ago, when his square-faced handsomeness made him an international icon of suave, Continental sophistication. Waiting to be summoned, he chain-smoked and coughed, telling stories in prismatic English, shrugging while his audience laughed. His thick hair has turned grayish and his hands shake; he is as dissipated-looking as Sophia Loren is an advertisement for health and careful living. I remarked to Altman one evening that Loren must really take care of herself. He looked at his watch. It was about 8:30. "By now," he said, "she's gone home, had a little supper, and gone to bed."

Bacall openly snorted her contempt for the acting ability of certain colleagues.

Mastroianni and Loren often sat huddled together in a little private dressing room set aside for them, a small, peaceful principality within a more disorderly fiefdom. Loren's voice is a flat, low flush, a rich bassoon, a reed instrument; you can hear the air vibrating through her sinuses. You wonder why such an odd voice doesn't mar her attractiveness, but the slight crack in her delivery adds to her allure, gives her a thrilling expressive quality that sounds especially good in duet with Mastroianni, who buzzes like a smoke-scraped vacuum cleaner.

They are old friends who have made more than a dozen films together. And after all these years they still seemed to amuse each other. Were they once in love? You couldn't help wondering when you observed their interaction. Loren laughed as she recounted one of Mastroianni's confessions to her.

"He complained that the only thing that still goes up with him are his toes," she said. Between delicate honks of laughter she said, "He must have holes in his socks." Mastroianni, hunched and shrugging as usual, went along. "It's a good thing I have someone sewing for me," he said, and pantomimed darning socks.

Mastroianni loved working with Altman, whose freewheeling ways reminded him of Federico Fellini. Like Fellini, Altman had told Mastroianni that he was open to all ideas. And so Mastroianni, who plays Sergei, an Italian stranded for 40 years in Russia, had himself an idea: "I ask Robert, 'Should I say a few words in Russian?' He says, 'Good! Great idea!'" Mastroianni laughed the laugh of good-natured defeat. He knew that he had been humored by Altman. "So I say, 'So where should I say them?' He doesn't answer. So," he said, shrugging, "I don't ask him anything anymore."

The surprise was that Mastroianni wasn't put off by Altman's polite but nonspecific response. "I love to work like this," he explained. "You come in, you don't know what's going to happen next. Eet's wahnderfool! I don't like to know."

"Just like in life," I suggested.

"Also not so much. In life, whether you want to know or not, you don't know."

"So," I said, repeating a joke Altman had once told me, "do you know how to make God laugh?"

"No, how?"

"Tell him your plans."

I couldn't understand why someone who knew as much as Mastroianni did about filmmaking wouldn't want to direct.

"I tell you. Very simple. You have to have so much confidence. You have to believe in yourself so—what's the word?— strongly. Then you have a script. You have to show it to your wife. She tells you it's no good." He drew on his cigarette. "Then, maybe, in some circumstances, you have a mistress." He shrugged, as if such a thing had never happened to him personally, but if it had, he could just imagine how complicated it could be. "And she says, 'Maybe there's a part for me?' Then you have a producer." He paused again to smoke. "And he tells you what he thinks. Then he has a mistress. Maybe there's a part for her?" Mastroianni shrugged again. He has large round eyes shadowed by the overhang of a ledge-like, deeply lined brow. He closed his eyes and opened them widely. "You have to believe in yourself so much, and have so much confidence. I do have, just enough to be an actor, but not like that," he said, waving his cigarette vaguely toward where Altman was out in the darkness demonstrating directorly reserves of confidence.

Ute Lemper lay backstage waiting for another show to begin. In October, when Altman asked the singer, then three months pregnant, if she would appear in the film nude as an eight-months-pregnant model, she considered the offer coolly, and agreed.

Altman couldn't tell her much about the role, because we hadn't done much more than conceive of it. He promised to work out the details later. But by the time the shoot began, her character, Albertine, who was originally invented as part of a Proustian subplot, was still a vague persona. Hardly anything she said in the film was scripted. A trained stage actress and chanteuse who likes to know the lyrics of her songs before going out to sing them, Lemper was unnerved by working this way.

"I don't like this," she said, stretched out on a couch. She had remained slender through her term and looked a bit like the Saint-Exupery drawing of a snake that had swallowed an elephant. "I'm embarrassed to go into the shows and just hang around. I'm making a fool of myself. I'm a shy person. I can't do this. Why does Albertine hang around? A pregnant model doesn't have something better to do?"

Many of the actors were flustered. Kim Basinger came backstage after the shoot. "How did it go?" I asked.

"Don't know. I've never worked this way before. It's a frightmare. I'm mispronouncing names. It's awful."

Stephen Rea mentioned that had things worked out differently he might at that moment have been acting in Roman Polanski's Death and the Maiden, also being shot in Paris.

"It was on and off and on," he said, "and during a time that it was off, Bob asked me to do this film. I agonized and I asked myself, If someone has one day to live, would he want to see a film about torture in South America or about the French fashion world? Bob just said to me, 'You're better off doing this film. It would be better for you.' And there's no one whose judgment in cinema I respect more."

Rea's expressions carry in them something of the sharp but unthreatening awareness and sensitivity of a devoted spaniel. Even his wavy hair hangs alongside his face like silken floppy ears. And everything he says gives further proof of his empathy and intelligence. But he doesn't say much in Pret a Porter. Mostly he sneers.

On the day of our rendezvous with Anouk Aimee at Sonia Rykiel's atelier on the Boulevard Saint Germain, I finally allowed myself to believe that the picture might actually get made. Aimee was playing Simone Lo, a designer whose character was originally inspired by Rykiel. Altman and I were at the atelier with some others to discuss Aimee's look in the film.

Aimee, at 62, is still beautiful, with a face that carries a bit of anguish for lost love around the mouth and girlish hope for what might come next around the eyes; it apparently remains untouched by surgical tools. The body is a bit broader than in her La Dolce Vita days, but the magnetism is undiminished. She tried on various trousers and skirts and jackets, holding her hair up and letting it fall at the suggestion of her rapt audience. Should she crop it short and curly like Colette or helmeted and sleek like Louise Brooks?

Rykiel said, "It's not important what she Wears. It's how she feels. I Hate the word 'Comfortable.' It's the way she Walks, and Eats—the way she does anything." Rykiel tends to talk in capital letters. I kept thinking, Yes, Sonia, but what is she going to wear?

Aimee finally asked, "Is Simone une femme sensuelle?,, Yes, everyone agreed. "Ah, good. I think Simone has to look like an artiste, not like a well-dressed bourgeoises Aimee explained. "That's what this movie is about—the difference between a well-dressed bourgeoise and an artiste."

Before we left, Altman gave Aimee an affectionate kiss and asked if she was depressed. Sheepishly, she said yes.

Altman sniffed. "If you're depressed here with the total attention of six people focused on you, then that's not neurotic, that's psychotic."

"No, no," she said, "I'm just thinking."

"That's depressing," he said. "When actors start thinking, that's depressing."

Every time Altman shot a scene, he contended with a roomful of thinking actors.

Rupert Everett, the star of Another Country and The Comfort of Strangers, plays Simone Lo's son and business partner. Everett was lying on the floor backstage one day, waiting. Passing him by, Altman looked down and said, "How are you?"

"Freaked," Rupert replied.

Altman kept walking. "Me too."

The tight budgeting for which Bob and Harvey Weinstein, brothers and cofounders of Miramax, were famous had been driving Altman crazy. Altman wanted $20 million to make Pret a Porter. Miramax proposed $17.5 million.

"Until yesterday, the deal was off," Altman told me on the telephone one day. "Then we set a deal on a conference call with Bob Weinstein, [Altman's agent, Johnnie] Planco, and that pip-squeak [Richard] Gladstein [head of production for Miramax]."

Talking to Bob Weinstein about the inadequate budget, Altman said, "I'm surprised at how little you know about this business. What happens if it goes over budget?"

"The completion-bond [the insurance company] people will take over," Weinstein said.

"The minute the completion-bond people take over my picture, I'm gone," Altman said. "I'm just trying to be realistic."

"Well," Weinstein said, and here Altman made Weinstein's reply sound huffy, "if that's your attitude, maybe we shouldn't make this picture."

Altman continued, relishing the story: "So I said, 'O.K., let's forget it,' and hung up." About five minutes later, he told me, Planco called and said, "What happened to you? Weinstein apologized for about 10 minutes and then we realized you weren't there." Altman sniffed loudly.

"They're totally inexperienced at this producing scene," he said of Miramax. "They spent their lives picking up little pictures [as distributors]." He paused. "There's going to be some unpleasantness."

Yet here in Paris, as pleasant as could be, was Harvey Weinstein, telling me that he was going to be a passive observer on this film. "I feel ridiculous about arguing over money with Bob just a couple of weeks ago," he said as we sat in the international terminal at Charles de Gaulle Airport, watching Altman shoot a complicated tracking shot. The actors, in character, were picking up their luggage from the baggage-claim conveyor belt.

"I come here," said Weinstein cheerfully, "and I see all these major movie stars who are used to having their own trailers and they're sitting in one big tent like summer camp. No one but Bob could do this. I look around and I realize that it's unbelievable that he's making this picture for this amount of money. It's the most complicated shoot I've ever seen."

A director making a movie is, by definition, operating in a state of crisis, practicing cinematic triage. Whatever can go wrong probably will go wrong, and the director will have to decide what to do about it.

Danny Aiello wondered, loudly and often, when he'd get to see some lines for his scenes with Teri Garr. And why, he wanted to know, did he have to stay in Paris for the full 10 weeks of the shoot, doing nothing most of the time? Did he tell Altman how upset he was? No—he knew Altman was in a state of crisis.

Rea received new lines one night. The next morning he coyly asked me if I had written them. I told him no. His facial muscles relaxed and he said, "Thank God, they're awful. Do you have any ideas for improving them?"

I asked him if he'd told Altman what he thought of the lines. "No," he said. "I don't want to bother him."

No one wanted to bother him.

Altman didn't want to bother them, either. If an actor delivered a performance that was less than fabulous, you never heard Altman say anything but "Cut. Very good. Let's do it again," the same comment he made after a superb performance. On movie sets throughout the world, it is clear, no one tells anyone the truth.

That's the way everyone likes it. On March 31, when Aiello threatened to punch Rupert Everett in the jaw, it was a refreshing surprise to hear someone candidly stating an intention on which he seemed determined to make good.

The set was the Chateau de Ferrieres, an expansive former Rothschild estate 40 minutes from Paris. Richard Grant's character, the designer Cort Romney, was staging his show in an opulent ballroom there. Loren, in her role as Isabella, the fashion executive's widow, was required to faint after the show. Aiello said he had asked Altman if his character, Major Hamilton, a buyer for Chicago's Marshall Field's department store, could say something about giving Isabella mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Altman said fine. But, according to Aiello, when they shot a take, Everett improvised a response to the line, saying that mouth-tomouth from Major Hamilton would make Isabella sicker. Aiello, who had become sensitive about playing a character who is an unlikable boor, took umbrage. In what is reportedly a fairly common turn of events on movie sets, many of the cast members were treating Aiello as if he himself were an unlikable boor, rather than just playing one.

"I'm just doing what Bob tells me and they treat me like I'm a jerk," he complained to me afterward. Exasperated, Aiello said, "I told Rupert if he tried that again I'd break his fucking jaw. Stephen Rea was holding me back. I said, 'Get your fucking hands off me'—excuse my language. Bob came over and I said, 'You have to tell them that I'm just doing what you say to do.'"

Aiello said the tension had begun earlier in the day when he and the other actors were sitting in the audience waiting to shoot the scene. Aiello was singing to himself and, he said, "Bacall turned around and said, 'Shut up.' I said, 'Who the fuck do you think you are?' Rupert came to her rescue. It's good that all the tension is out," said Aiello about the incident. "Now we all know that we hate each other's guts."

From that point on, Aiello snidely referred to the British contingent of actors as "the Shakespeareans" and refused dinner invitations that included Bacall. Bacall didn't hold back about her feelings for Aiello, either: "All that macho bullshit. I know those Italian guys. I've been through that war."

Bacall rarely made a secret of her likes and dislikes. She openly snorted her contempt for the acting ability of certain colleagues, particularly Aiello. She was especially well known on the set for publicly venting spleen, sometimes against workers who lacked the clout to defend themselves. On the last day of the shoot at the Bois de Boulogne, she and I got into a van with a driver and waited for some of the remaining six seats to be filled. The captain of the drivers, Eric Duchene, was running around looking for other actors who might need a ride.

Bacall said to the driver, "Let's go," but he explained that he had to wait for Duchene to dismiss him.

"Well, I can't wait," she said. "I want to go now." The driver explained again that he couldn't leave.

Bacall, furious, opened her window and shouted, "Eh-reeeek! Eh-reek! Where is that idiot? I want to go now. I'm not going to wait for him to fill this car." After a few minutes, Aimee joined us. Bacall resumed her bitter deriding of Duchene's intelligence and competence. Finally, Duchene gave the driver the O.K., and we rode into town.

Perhaps it is because he was on the set for only two days that Harry Belafonte seemed so enchanting. He is the most charming person I've ever met who is also intelligent and dazzlingly beautiful, and I suspect he would be so even longer than 48 hours. Just as something in Altman's paternalistic nature makes people seek his approval, something in Belafonte encourages sexual display. Even at 67, he is a habitual flirt.

Poor Kasia Figura, a Polish actress in her 30s, had told me she had a crush on Belafonte. When she spoke to him she giggled nervously and stood with her shoulders thrown back militarily, a posture that showed off two of her more outstanding aspects. Belafonte knew perfectly well the effect he had on her; a man of his experience had to recognize that he was shooting fish in a barrel. He stood close to Figura and told her how lovely she looked. I feared that she might faint, but moved away so that in case she did topple over, Belafonte would have to catch her and then Figura could at least say that Harry Belafonte once held her in his arms.

Belafonte's charm is all smoothness and grace; Mastroianni's is the charm of self-deprecation and puzzlement. Waiting to be called to the set, Mastroianni asked Belafonte, "What is your real last name?"

Belafonte said, "Schwartz."

"Ah, you're Jewish. Are you circumcised?"

Without waiting for an answer, Mastroianni offered one of his many theories. "It's a plot by women to get better sex. With a foreskin, the penis is very sensitive. In and out a few times and climax." Quite a bit of sawing in the air and something resembling diving into a swimming pool accompanied those last eight words. "Sneep off the foreskin," he continued, "and it takes longer, and the woman gets pleasure too." Here he closed his eyes, smiled, and uttered a satisfied, upperregister "Aaaah."

Perhaps Mastroianni's character, Sergei, suffered from a surplus of foreskin. Whatever the reason, in the film Sergei was unable to elicit the utterance of any upper-register "Aaaah"s. The target of his affection was Loren's Isabella. At the Grand Hotel, Loren rehearsed getting into bed with Mastroianni. The scene was modeled after one they'd played together in Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, 32 years before.

"It has the same music as the old movie," Mastroianni explained. "She was a prostitute and I came to her. She does a striptease, but we don't fock. Because she is in love with a priest. And she promises if he go bock to chairch she no fock for a year. In the end of the scene, we pray." He held his hands together in front of him and looked toward the ceiling.

Loren sat out of the sun in a darkened garage in the Musee Rodin's garden. She was wearing one of the movie's many improbable Jean Barthet millinery fabrications that only someone with her unearthly symmetry could support, and a black, body-hugging, 1950s Dior frock reconstructed for the film. With her legs crossed and a napkin in her lap, she chewed on a huge baguette sandwich, now and then dodging tomato drippings, eating like a woman who gets too hungry for dinner at eight even though she is dressed for it.

The Musee Rodin is one of the film's emblematic Paris backdrops. Sergei, still in love with Isabella, has begged her to meet him in the Rodin garden in front of The Thinker so he can explain why he "disappeared" many years ago. Loren, as Isabella, walked straight up to her lovesick swain, steadied herself, hauled off with a right to the jaw, and marched on indignantly.

Between takes, Loren returned to Mastroianni and rested her powerful hand softly on his stricken cheek, smiling at him.

So many films, so many slaps.

"Yes," she said, "he's accustomed to my slap. He remembers my slap."

Did it hurt?

"Noooo," he cooed, "she is an artist."

"Yes, it does," Loren contradicted. "He's crying inside."

Mastroianni continued to praise Loren's fine-tuned control. "She makes a beeg gesture, then she comes to my face and it's—" And his hand halted like a bumper just missing a brick wall, to the accompaniment of sound effects.

"It's like a cartoon," said Loren, delighted.

Danny Aiello has great legs. We saw them for the first time when he slipped into the pink Chanel-ish suit Major Hamilton wears to his favorite crossdressing restaurant. Catherine Leterrier, the costume designer, was fussing with the chain belt, which didn't lie right against the nubby wool fabric: although Aiello, who is six feet three, has many lovely attributes, a pair of hips doesn't happen to be one of them. "My mom had the same problem," he explained.

Fully dressed, Aiello stepped back to examine himself in the mirror. A white silk shirt with a f louncy bow at the neck and a conservative shoulder bag completed the ensemble. With his left hand he gripped the strap of his shoulder bag as if it were the reins attached to a bucking bronco. Trying to relax, he opened his palm and spread it restfully on his left falsie.

"This hand is bugging the shit out of me," he said, jerking it from his breast. "Oh, my feet hurt. Oh, God in heaven, God bless you women. I don't know how you walk." Size 12E beige pumps with black toe caps had been made for him.

"You don't think the boobies are too big?" he asked as he stuck his chest out. "It looks like they're really out there." He fussed with the handbag. "I look like Margaret Thatcher."

Aiello had known since early March that he would have to try on his costume for size. He waited until April 28 for this fitting, and even then he refused to allow anyone but Leterrier and a few friends in to see him. Catherine Pouligny and Pascal Mourier, the video crew making a documentary about the film, begged to be allowed to record his transformation on camera, but in embarrassment he refused. Now, however, smiling at his high heels in the mirror, he asked that the crew be summoned. When he was ready to undress, he asked them to stay. "You have to see this bra," he said as he stripped.

Mourier and Pouligny were thrilled with the footage. Later I asked them whom they still had to interview. "We hope Marcello," said Pouligny, "and we fear Lauren Bacall."

Several hours before he was to shoot a long, complicated party scene staged at the old Parisian restaurant Ledoyen, Altman was sitting in his office, wishing the day were over. The jeweler Bulgari was sponsoring the party, and had sent out 250 invitations to prominent Parisians and fashion-world celebrities. A list of the actors' characters' names was included, and guests were asked to address all actors by their fictional names, or if memory failed, call them "Darling."

Altman was playing solitaire, which he does to relieve anxiety or boredom the way some people pick their cuticles or finger worry beads. He was telling me about the difficulty of coordinating actors and nonactors in the frenzied context he was about to create. He asked me if I wanted to come and look the set over. Just before we were to leave, Scotty Bushnell ambushed me when I was alone in Altman's office.

Bushnell, Altman's longtime producer, right arm, and head cheerleader, did costumes for Thieves Like Us in 1974. Since then, her credits have included associate or executive producer on just about every film Altman has made. Somewhere near 60, she looks a bit like a dark-haired Leni Riefenstahl sucking on a sour candy. Bushnell is the only person I know over the age of 50 who interrupts her own speech with the verbal tic "like." Early on, she informed me that I should never meet with Altman unless she was present. She also told me I was barred from the set for the first few days of shooting, an edict I ignored.

The day of the Ledoyen shoot, she lectured me. "This is going to be a strenuous day. I'd appreciate it if you'd, like, keep your idle chatter to a minimum." I looked at her for a moment. Then I asked, "Do you plan to keep your idle chatter to a minimum?"

She peered directly at me for the first time. "Look, it's a rough day. He needs to concentrate." I remembered what Kathryn, Altman's wife, had said to me about Bushnell having no life other than Altman and his films, and I restrained myself. "I wasn't aware that I was off the topic," I said, and laughed. Then, as if I were in a movie myself, I uttered a tough-guy cliche exit line—"You're really some piece of work"—and walked out of the room, grateful that the right door was nearby.

When I told Kathryn the story, she said to me, "The real surprise is that people are complaining so early about Scotty. Usually you hear about it at the end of the film."

Altman had more pressing personnel problems than Bushnell. "The crew has been unbelievable. I have to do everything myself." He interrupted himself as several crew members carried a mattress through the corridor of the Grand Hotel, shouting at one another.

"Why are they screaming?" he asked. "I'll never do this again. I'd rather be unemployed than do another French film." You could see him lost in a moment of self-examination, and then, as if admitting a lie, said, "This is my fourth French film." Amused by his own recidivist nature, he sniffed, and then almost smiled. "I say that every time. Of course, if this is a big hit . . . " He shrugged. For a hit he'd work with a crew that spoke Urdu.

Altman had asked the actors to take off their clothes in a scene featuring a clothing less fashion show. At a picnic on the grounds of the Chateau de Ferrieres, the subject turned to the impending nudity. The actors presumably had agreed in principle to the possibility of appearing nude when they signed on, but now, several weeks into the shoot, the urge to disrobe in public was abating.

"Forget it," said Tracey Ullman. "I breast-fed two 10-pound babies." She repeated, "Forget it."

Rupert Everett, his voice syrupy with mock artistic integrity, sang, "My character wouldn't take his clothes off."

"Have you shown your thing in movies before?" Ullman asked.

"I've shown it in every movie," he replied. "I make a point of it."

Altman first described the nude fashion show to me in ecstatic terms: a triumphant Simone Lo sends her happy models out on the runway wearing nothing but the flower petals raining down on them, and the audience approval is so fervent that people in the crowd tear off their clothes in gleeful, celebratory support. I couldn't imagine it. Altman told me he'd seen such a spontaneous gush of exuberance once. He served in the Pacific during World War II and when the soldiers learned that the war was over, everyone stripped in a display of bacchanalian joy. I didn't see how those sentiments could be translated into an aesthetic appreciation of Simone's anti-fashion statement, but wrote the scene as he described it.

I was ill the night he shot it at the Musee de Cluny in the Quartier Latin. But when I saw the dailies I was moved by what he had achieved. Unlike his descriptions to me, the actual scene was dirgelike, with the models marching gloomily to "Pretty," the Cranberries' eerie minorkey moan-chant. The tall, emaciated women, their mouths set in morbid pouts, trudged along the catwalk as if to their mortal ends. The echo of a death parade, of Auschwitz inmates slouching toward the gas chambers, was unmistakable. It was the kind of comment you might expect of a director at the end of his career and his art—which Altman certainly is not. But for him, and for Simone, mortality is no longer just a theoretical notion.

The dark tone contradicted his stated aim for the film. All through our writing sessions he kept telling me he wanted to make something "light." Whenever I said I couldn't fathom a film about the fashion world that didn't mention AIDS, he'd tell me this was going to be "light."

After the dailies Altman asked what I thought about the scene. I told him that I found it unusually beautiful but a complete surprise, given his earlier descriptions. "You always spoke of it in celebratory terms. Then you shot it as a funeral march."

He laughed. "I never know what I'm going to do until I get to the set."

Altman's joy in taking risks keeps him young. He's told me that he doesn't think he's very intelligent and so he has to rely on his other strengths—his intuition, his ability to spot fakery, and his willingness to gamble. An experienced risktaker is constantly replenished and exhilarated by all he learns from giving a chance to a new person, or following the logic of an unproven notion. Altman seems to know that he can handle the consequences when a risk he takes goes wrong. He isn't afraid of failure. He sees something noble in what other people call failure. He doesn't believe in the possibility of failure, that it can exist for a serious artist. He can bomb at the box office, but if he's worked hard, he can't really have failed. Pret a Porter is still being edited as I write. But for Altman it is already a success.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now