Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

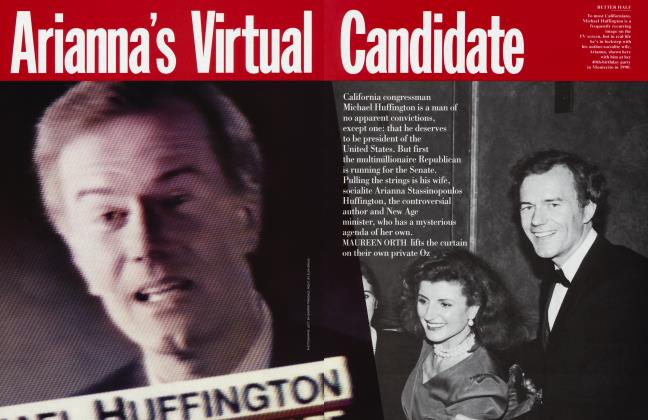

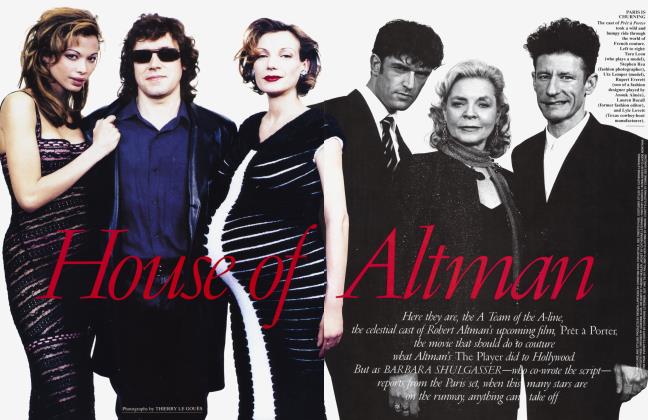

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowKENNEDY DIPLOMACY

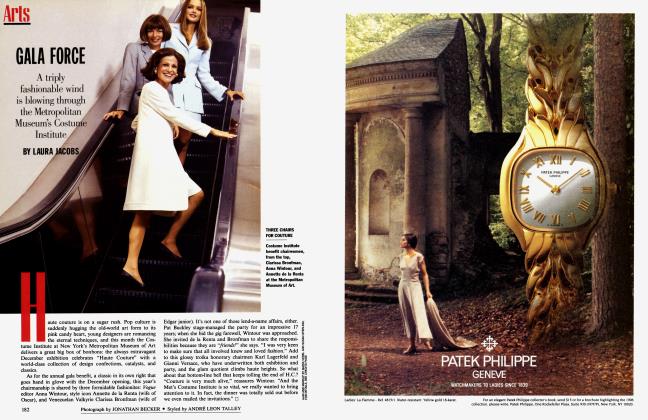

The Kennedy legacy is alive and well in Ireland. J.F.K.'s picture still hangs on many walls; Teddy is still revered; Jean Kennedy Smith is the U.S. ambassador. Together, they helped broker the deal that brought about the I.R.A. cease-fire

Letter from Ireland

LESLIE

ANDREW COCKBURN

'Knight Dame Jean Kennedy Smith!" bellows an elderly gentleman wearing a costume best described as Roman epic. His plum-colored tunic is complemented by a silver helmet, leather sandals, and white athletic socks. "The socks make it," murmurs director Mike Nichols as we watch the American ambassador to Ireland invested as an Irish knight.

The skulls of dead deer gaze down on this bizarre ceremony, which is all of 11 years old and is taking place in the baronial hall of Muckross House, an extravagant Gothic pile thrown up beside the lakes of Killarney in the 19th century thanks to an Irish-American mining fortune. The lithe 66-year-old ambassador, sister of John and Bobby and Ted Kennedy, steps forward to receive her vestments and kiss a formidable-looking sword. The barelegged master of ceremonies motions for her to kneel. She remains determinedly upright, prompting whispers around the hall. "She can't kneel, because she's an ambassador."

The championiig of Paul Hill is a telling indication of how the Kennedys regard their ancestral homeland.

"She's got a bad back."

"I think," says one Irish dowager, "she's religious."

The awkward moment passes, and the assembled company of wealthy Irish-Americans and other friends of our Califomia-bom host breaks into a rousing chorus of the "Knight's Anthem," to the tune of "The Whiffenpoof Song," the refrain of "Baa Baa Baa" being replaced with "Rah Rah Rah."

The ambassador takes it all in good humor, as a pleasant social occasion of the kind that has traditionally occupied the time of American envoys to Ireland. The Irish have not forgotten or forgiven the fact that until Smith arrived the post was usually reserved for elderly IrishAmerican nonentities who made their way to the Emerald Isle via assorted presidential campaign coffers. "Dead before he arrived," sniffs one Dubliner at the memory of a notably geriatric Bush appointee.

No one argues that Jean Kennedy Smith fits that mold. "There are the Irish-Americans and then there's the Irish," says Sean Donlon, himself a former ambassador, from Dublin to Washington. "The Kennedys are Irish. They really understand Ireland— beyond all this." He waves a glass at the crowd under the stag skulls.

The Kennedys' understanding, or at least their interest, is of comparatively recent vintage. Even after they made their millions, the family never bothered to keep a house in Ireland. Jack's election, whatever it did for the Irish emotionally, did not pay off politically for their country, and Bobby, for all his fervent crusading on behalf of oppressed peoples, never took any interest in Ireland. The Kennedy interest, says Donlon, dates from "'69, when the North blew up."

"The North"—the six northern counties that Britain refused to relinquish when the rest of Ireland gained its independence in 1922—was dominated by a Protestant majority, who, enamored of their link with Britain, called themselves Unionists. They were determined to prevent Catholics in the province from getting any measure of political or economic power, still less reuniting with the rest of the country.

In 1969, the northern Catholics finally rebelled. The British sent troops, initially to keep Protestants and Catholics apart, but they were increasingly seen by the Catholics as reinforcing British domination and their own subject status. The Provisional Irish Republican Army, descended from the old guerrilla force that had driven the British out of the South, took up arms to complete the job. As the war dragged on, it became a metaphor for intractable conflict.

Throughout "the Troubles," the U.S. had left Northern Ireland pretty much to the British, consistently refusing even to allow entry visas to the I.R.A. leadership, specifically Gerry Adams, the president of the I.R.A.'s political arm, Sinn Fein. Finally, in February of this year, Adams got his visa and came to the United States for a 48hour media blitz. And then, in August, the I.R.A. declared a "complete cessation of military operations." Astonishingly, it appeared that Ireland could be near the end of a struggle that has lasted for centuries.

An American diplomat with an intimate knowledge of the Irish situation recalls vividly that "Teddy [Kennedy] went out on the line for this thing. The president made promises during the campaign to Irish-Americans, particularly in New York. In the New York primary a group met with Clinton. That was where the commitment was made to give Adams a visa. Clinton is no green-tie president—he doesn't just drink green beer out of a bowl on St. Patrick's Day. He got into the specifics of the issue. But it was Kennedy, along with his sister Jean, who kept the promise."

"There is absolutely no doubt that without Ted Kennedy there would not have been a cease-fire," says Niall O'Dowd, publisher of the Irish Voice in New York, who helped map out the strategy for the cease-fire. "Getting that visa was crucial. It told the Provisionals that the American involvement was real."

(Continued on page 67)

(Continued from page 58)

"There is absolutely no doubt that without Ted Kennedy there would not have been a cease-fire."

"It was Bill Clinton saying to Adams that he was sticking his neck out. He was bucking 50 years of U.S. foreign policy," adds former congressman Bruce Morrison, another important player in Northern Irish negotiations. "That had to tell Adams something. Jean stuck her neck out, too."

awrence O'Donnell, the top aide to Senator Pat Moynihan, remembers that when he and the senator "heard about the Adams visa request from Kennedy, there was really only one question: What does John Hume think?"

Deep in the Catholic ghetto in the British-ruled city of Derry, John Hume is driving us past a huge mural of a small boy in a gas mask carrying a gasoline bomb. Hume, a 56-year-old former schoolteacher, is the leader of the Social Democratic Labor Party, which gets its votes from the North's Catholic minority. He is also, crucially, the Kennedys' alter ego in Irish politics.

As we pass a street of terraced houses he slows to point out where Jean Kennedy Smith came to stay in 1974, when the I.R.A. military campaign was at its height. "That's my house. It's right in the middle of the Bogside. In the early days of the Troubles I used to have a terrible time with the I.R.A. They used to picket my house, paint my house, firebomb my house, and I stood up to them."

Hume was reviled by the I.R.A. "Provos" because, though he was a Catholic leader, he denounced the military campaign against the British. This was a potentially lethal position for someone living in the Bogside, but he refused to carry a gun. "If you're preaching nonviolence, you practice it." Instead, he forged a weapon even more potent than the armory of the Provos— an alliance with the Kennedy family that brought about an increasing involvement of the clan in Irish affairs.

The British government found out just how powerful that alliance had become in February, when it appeared that President Clinton was actually going to authorize the visa for Adams. Sir Robin Renwick, the British ambassador to Washington, raged and fumed, denouncing Adams as "Goebbels," while enlisting old friends in the State Department to stop the visit.

"It's very hard to find the line between the State Department and the British Foreign Office," says Bruce Morrison. "I mean, whenever the question of Ireland came up you'd hear people from State say, 'What about H.M.G.?'— Her Majesty's Government. That turns my stomach. I mean, we fought a revolution over here. Seitz [then the American ambassador in London] sounded like he was working for the British."

But this time the old "special relationship" failed to hold up. A senior official from the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs recalls with some glee how Renwick was on one occasion waiting to see Clinton and had to watch John Hume being ushered in first: "The eyes were popping out of his head." The diplomat smiles. "Hume has clout—his relationship with the Kennedys."

Hume remembers clearly the beginning of that relationship, back in 1972. His hometown of Derry was a ruin. The city center was gutted by Provisional I.R.A. bombs. The streetlights had been shot out. Nights were punctuated with bursts of automatic-weapons fire. British-army tanks had swept away the barricades defending the Catholic ghettos. "I'm lying in my bed in the Bogside," recalls Hume, "and the phone rings and the voice says, 'This is Ted Kennedy.' And I say, 'Pull my other leg.' And then I realized it was him. He said, 'I'd like to have a long chat with you. I want to find out exactly what's going on.' "

Hume speaks quietly, smoking his way through our pack of cigarettes in the Monico Bar in downtown Derry, his voice nearly drowned out by Tina Turner. Thickset in an ill-fitting suit, with a faint gray streak in his shock of black hair, he cannot get through a conversation without an interruption from a constituent. One wizened old man approaches and then breaks down in tears as he confides in Hume about the death of his brother.

When he took that original call from Kennedy, Hume was an obscure 35year-old member of Parliament with a J.F.K. poster on his wall that read, ONE MAN CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE. At the time, American involvement in Northern Ireland was limited to a flow of money for guns from NORAID, the I.R.A.'s U.S. fund-raising arm. But Kennedy's invitation to Hume to visit the United States triggered the birth of a new lobby. "Our main concern at the start was that the traditional IrishAmerican thing was quite simplistic about Ireland, with a lot of support for violence," says Hume. "That is why I decided to go to Washington."

Kennedy introduced him to other leading Irish-Americans on Capitol Hill—Senator Moynihan and Congressmen Tip O'Neill and Hugh Carey. "They founded a body which we called the Four Horsemen. They presented me with a magnificent picture of the four of them on horses," Hume remembers. It was the first seed of what is happening now. As Hume likes to point out, the 42 million Americans who stated they were Irish in the last census have made a difference.

Dublin politicians, not always a charitable breed, say that Hume's highminded diplomacy can get a little out of hand. "Ethel Kennedy gave a dinner one night" in 1985, recounts one from behind a cloud of cigar smoke at the Kildare Street Club, "and Ethel plays these games. She asked everyone around the table if they were sexually attracted to Maggie Thatcher. When it came to Hume he said, 'I think of Margaret in the same breath as John Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy.' We all looked at each other. Then he went on to talk about their great work with the civil-rights movement and the great potential for Maggie to make dramatic progress in Northern Ireland. You just wanted to be sick." Nevertheless, when it comes to Washington access, the Dubliners are happy to regard Hume as "one of our own."

"John created a credibility for himself in Washington that was extraordinary," says Morrison. As another American politician explains, "John looks you in the eye and says, 'I live there, I'm the one they want to kill.' He'll spend eight hours with you and when he leaves he says, 'My people keep electing me.' Politician to politician, that's very effective."

(Continued on page 73)

(Continued from page 67)

Hume certainly had an effect on Jean Kennedy Smith. He is "the biggest single influence on her," says Joe Lee. A rumpled professor from Cork, Lee is a close adviser and tutor to the ambassador. Ensconced in a booth in the Horseshoe Bar, a watering hole for the Dublin political establishment, he explains that not only is Jean Teddy's ambassador to Dublin, she is Hume's as well. The Irish government in the South "has to have pressure on it that reinforces Hume's ideas," says Lee. "She's an important conduit for Hume."

It's not entirely clear why Jean Kennedy Smith (who declined to speak to Vanity Fair for this article) decided to take up diplomacy in her mid-60s. Her sudden interest certainly came as a shock to Congressman Brian Donnelly from the very Irish district of Dorchester in Boston. He had worked long and hard on Irish matters, wanted nothing more than the Dublin embassy, and thought he had been promised the post by the Democratic leadership. "Brian never saw the fucking train coming," says a friend. Donnelly later reported that when he solicited Senator Kennedy for the job, Kennedy replied, "Oh shit, my sister is interested—but you deserve it."

But a Clinton official states the bottom line: "Jean can call her brother in two minutes, and he can call the president. That's important."

Ted Kennedy "cares about this stuff to a surprising degree," observes Lawrence O'Donnell. "Remember how Robert Frost told John Kennedy to 'be more Irish than Harvard'? Well, it's extraordinary how much more Irish than Harvard Ted is. ... I mean, look at his office—it's full of Irish memorabilia, a street sign from Ballysomewhere. He feels very strongly about it, quite emotional."

Of course, it does not hurt that Massachusetts is 26.9 percent Irish. Kennedy is running in what may be his closest re-election race in years, and his labors on behalf of the old country help to cancel out a lot of scandal-ridden baggage accumulated over the years. Albert Reynolds, the Irish prime minister, even went to Massachusetts this spring to give a campaign speech for the senator: "Six more years!" Conservative Catholic Democrats will forgive a lot on behalf of Ireland.

Though his sister has been careful to include Protestant Unionists at official dinners at the Phoenix Park ambassadorial residence, she is also known for her gut Irish nationalism. "Her position is: 'Brits Out'—I didn't tell you that," says one friend.

"The name Kennedy brings the British out in spots," says Dorothy Tubirdy, the family's oldest friend in Dublin. "Dot," as she is known around town, is a society matron and a former P.R. woman for Waterford Glass. She is also godmother to Courtney Kennedy, daughter of Ethel and Bobby, who was catapulted into the headlines when she married Paul Hill, known to history as one of the Guildford Four, the group whose story was the basis of the book and subsequent film In the Name of the Father.

In Ireland, the marriage of a rough Belfast street kid who has spent his entire adult life in jail to a member of what the Irish regard as their First Family was received with equanimity. "People here thought it was quite natural," says political commentator Fintan O'Toole with a shrug. "Come out of jail and marry a Kennedy."

When Hill's appeal of his conviction for murdering a former British soldier (long before his fraudulent conviction for the Guildford bombings) came up in Belfast, there were massed ranks of Kennedys in the courtroom to show solidarity. A suave Dublin political wheeler-dealer who doesn't let his longtime friendship with the family get in the way of a blunt remark says that "people here thought the Kennedys' trooping in in their Chanel suits and Gucci shoes was a bit tacky. No one paid any attention to Paul Hill's mother or his daughter."

But another point of view comes from a man who himself spent four and a half years in a southern Irish jail, wrongly convicted of a spectacular train robbery. Nicky Kelly, one of Hill's closest friends, is now a local politician in the South. "What would people have said," he argues, "if the Kennedys hadn't gone to the appeal? That they didn't support him. And it might have gone the other way. Can you imagine Ethel camped outside the prison?"

The championing of Paul Hill is a telling indication of how the family regard their ancestral homeland. "The Kennedys look at these people, Nelson Mandela, Cesar Chavez, Paul Hill— they're all in the same category," observes P. J. Mara, a fabled Dublin political spin doctor and friend of the family. It was Ethel, Mara points out, who selected Hill as a suitable friend for daughter Courtney, dispatching him to cheer her up when she was recuperating after a skiing accident. "Ethel was the matchmaker."

It was Ethel who selected Hill as a friend for her daughter Courtney. "Ethel was the matchmaker."

Congressman Joe Kennedy, Courtney's 42-year-old brother, has also been involved in pushing Irish interests, through his close association with Bill Flynn. In the unpublicized but increasingly potent world of the IrishAmerican lobby, Flynn, aged 68, is a name to conjure with. Chairman of the enormous Mutual of America insurance corporation, he used a foreign-policy group he endows to sponsor Gerry Adams's visit. The son of a Catholic emigrant from County Down in Northern Ireland, he is disarmingly frank about his interest. "I was approached by people from NORAID who asked me for a contribution. I said I couldn't do that, because I didn't agree with their methods, though I told them I did agree with their eventual goal—the reunification of Ireland. I've always wanted to see a United Ireland. Then they asked me, in a nice way but quite bluntly, 'Well, what are you doing about it?' I've never felt like a draft dodger before."

Flynn and young Joe worked to end discriminatory practices against Catholics in Belfast factories. And Flynn swung his considerable weight in U.S. business circles to foment support for the effort to persuade the I.R.A. to call off its military campaign in exchange for political respectability and endorsements.

While Flynn and the others did play significant roles in marshaling U.S. support for a breakthrough—and everyone emphasizes the enormous impact of the Kennedy-Hume axis—it is the I.R.A. gunmen who actually put down their weapons and locked up the bomb factories.

Sinn Fein documents going back to 1989 show that "the movement" had come to a decision that the vicious guerrilla war was going nowhere. Spectacular coups such as lobbing mortars at Heathrow Airport and bombing the City of London, prompting howls of anguish from foreign banks and corporations operating there, were an effective finale, a demonstration of the damage that could be done. The I.R.A. was improving its position at the table, and John Hume's role as Martin Luther King needed the steady gunfire as a backdrop.

At the Pilot's Row Community Center, within walking distance of Hume's modest house, we find some of these I.R.A. warriors and an ebullient crowd of their supporters commemorating the 25th year of the Troubles with a Provo version of the TV show This Is Your Life. After persuading the large men at the door to make an exception to the strict ban on outsiders, we squeeze into the back of the hall. A thick fog of cigarette smoke hangs over the bleachers as we strain to penetrate the Derry accents of the speakers, many of whom have done time in the infamous H-Blocks for Republican prisoners in the Maze Prison, outside Belfast.

"Here we have," shouts the master of ceremonies, "the longest-serving prisoner in Northern Ireland!" The crowd roars its applause while the ex-prisoner grins sheepishly. One guest leaps up. "I feel like I'm on a jury here," he shouts. He points at the honoree: "He's guilty." The laughter swells. "He looks guilty, he is guilty."

The honoree is a grandfather and revered community activist who has sheltered and fed most of the Republicans in the room at times when they were on the run. He beams as his scattered family appear on the video screen: a son in California, a gymnast daughter at the Commonwealth Games, a son with cerebral palsy. A letter is read out from another son, in jail in the South for I.R.A. activities: "Dad, you didn't teach me to run fast enough."

Gerry Adams, looking slightly stiff and awkward, appears on a taped message of congratulations. Finally Martin McGuinness, former I.R.A. chief of staff and commander for Derry and now vice president of Sinn Fein, takes the mike. McGuinness, once a hunted guerrilla, is trim, with curly blond hair. He wears a crisp blue shirt and tasteful tie. His message is about the successful end, fast approaching, of "25 years of struggle." A beefy veteran of the I.R.A. jumps up to shout, "Hey, Martin, what about our back pay?"

"Jean can call her brother in two minutes, and he can call the president.

That's important."

Later, as the crowd shuffles out into the night, McGuinness reveals how the evening's battle-hardened honoree was tricked into putting on a suit and coming to Pilot's Row for "This Is Your Life." "We told him Vanity Fair wanted to talk to him."

When the British secretly approached the I.R.A. last year, one of the key people they wanted to talk to was Martin McGuinness. "They invited us to go to either Norway, Denmark, Scotland, or somewhere else to meet their delegation," he recalls. "Then they got cold feet. It didn't happen. It was a year lost."

But pressure from Washington was being brought to bear. "We regard that [as] of crucial importance," says McGuinness. "As well as breaking ice with the British government, we've broken ice with the Irish government, we've broken ice with John Hume, and we've broken ice with fairly influential IrishAmericans."

Sinn Fein itself did not have direct access to the Kennedys, so it worked around the edges. "People like Bruce Morrison have taken a keen interest, Bill Flynn and others. I don't know if I should actually mention their names. The role that most Irish people would like the U.S. to play is—" McGuinness pauses. "I have to be very careful with choice of words, but we certainly hope that the American government would counsel the British government as to how they should move forward. The British just seem to have this paralysis when it comes to thinking how we should move forward politically."

For so long McGuinness concentrated on killing British soldiers and avoiding getting killed or captured himself. Now, with a weak British government and nationalists such as Hume and the Dublin government confident of powerful support in Washington, he and his colleagues are ready to deal. "We would like to see the eventual reunification of Ireland, but if we go to discussions with all the parties and the Irish representatives, including the Unionists, decide on another form of government, a federation, obviously from our point of view we would compromise about all these things."

So far at least, the Unionist politicians show little appetite for compromise, The Reverend Dr. Ian Paisley, longtime voice of militant, working-class Protestant Unionism, has denounced the British government for its readiness to talk to Sinn Fein. (After a heated row with John Major, he locked himself in the bathroom at 10 Downing Street.) For Paisley, if the British government is an abomination, the Kennedy family is anathema. Asked about the clan's involvement in Irish affairs, a spokesman at his Belfast office said brusquely, "Too much of it. They'd be better off trying to sort out the red Indians and the blacks."

In the rest of Ireland, there is no such hostility, or diffidence, certainly not about the local family representative. Jean is regarded with affection in Dublin, though with characteristic charity one of the Horseshoe Bar set observes that "she's a bit dim—no rocket scientist." A little awkward in smarter social gatherings (the complete text of her speech at the knighting dinner was "I've had too much wine and I'm not going to make a toast"), she displays a warm and deft touch among the people. In the tiny village of Kinvara, outside Galway, the ambassador is ushered into a pony and trap. She beams good-naturedly, claiming, "My mother used to go to school in this." She is joined by the beauty queen chosen for the local "hooker festival," a hooker here being the traditional sailboat of the region. A horde of village children in fancy dress surround her, murmuring, "Ooh, she's lovely." Peggy the pony pulls the ambassador down to the village square, where she is hailed as "a descendant of emigrants," just as her brother John was 31 years ago. The pipe band strikes up "When the Saints Go Marching In."

A year earlier, Jean Kennedy Smith presided over an even more nostalgic event. A few miles south of the town of New Ross, in County Wexford, off a narrow road, there is a tiny hand-painted sign on a farmyard wall: THE KENNEDY HOMESTEAD. Next to it, the newly arrived ambassador mounted a small plaque, easily missed, which states that this is the BIRTHPLACE OF PATRICK KENNEDY, GREAT-GRANDFATHER OF PRESIDENT JOHN F. KENNEDY, USA, WHO RETURNED TO HIS ANCESTRAL HOME 27 JUNE 1963.

When we arrive at the homestead, a middle-aged woman in a wool sweater steps through the gate. She has auburn hair and bears a faint resemblance to her third cousin Jean. There are kitsch lawn storks in the garden and a quaint red hand pump in the stable yard. Mary Ann Ryan looks guarded when asked whether the ambassador has been in touch. "Not since the visit last year," she says defensively. "She must be busy."

Gazing around the neat yard, we ask which of the two sheds produced the original Kennedy. "No, no, this one," she says, motioning to a third, even smaller hut, buried under ivy, that looks comfortable enough, for one person standing up. Inside there are yellowing clippings from the Kennedy visit in 1963. A wreath is turning to dust. The glass is chipping off a framed ode to John Kennedy and Pope John XXIII, who died the same year: "For two great Johns of '63, / Their hearts were simple, pure, and free, / They loved mankind and liberty."

The mementos date from the days when John Kennedy's portrait was hung on every Irish-cottage wall, "up there," as the Irish say, "next to the Sacred Heart." (Jackie used to be up there too, but most of her pictures came down when she married Onassis.) "The '63 visit of Jack," remembers Sean Donlon fondly, "was the beginning of the new age in Ireland."

Today, with A1 Gore proclaiming that "Ireland is top of the U.S. foreignpolicy agenda" and the Irish prime minister consequently emboldened to shake hands with Gerry Adams and call John Major an "eejit" to his face, it is clear that the most famous emigrant family is doing more for the country than just visiting.

During that 1963 tour, John Kennedy had a little routine he worked into every speech. "Does anyone here have a relative over in America?" he would ask whatever packed town' square he happened to be addressing. A forest of hands would shoot up. "I never realized," he would say with a smile, "there were so many of us over there."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now