Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBill and Hillary are off the Whitewater spin cycle and busy soaking up mea culpas from media softies, but the damned spot doesn't come out that easily

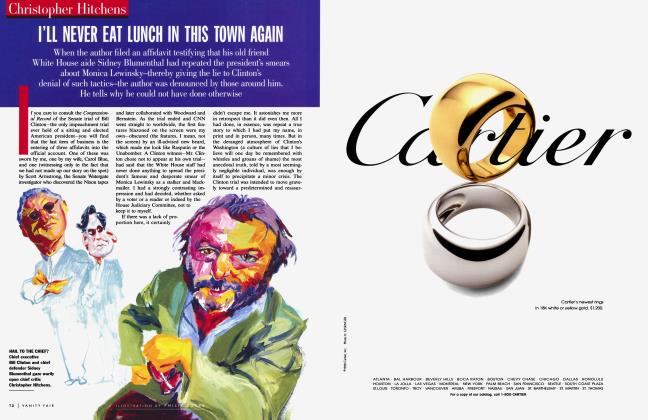

July 1994 Christopher Hitchens Philip BurkeBill and Hillary are off the Whitewater spin cycle and busy soaking up mea culpas from media softies, but the damned spot doesn't come out that easily

July 1994 Christopher Hitchens Philip BurkeLooking back, it seems as if the week between Passover and Easter was the time when the great Whitewater turnaround began and the Clintons started to pull away from the wreck of their Arkansas enterprise. An ingenious multiple "spin" had been in preparation for some time, to the effect that the whole inquiry was a waste of energy. The extreme complexity of the paperwork in the case was a great help, and so was the apparent smallness of the sums involved. Then there was the claim that the Clintons and their chums were being victimized because they were southern. Thrown in as a makeweight was the suggestion that, after all, the Republicans had gotten away with worse in their time and wasn't it a bit much to hear from Senator D'Amato about ethics, ha ha ha. Helpful, too, was the insinuation that if not for all this raking up of the past the country would by now be rolling in health care. Assiduously, it was maintained that all of the alleged offenses were prehistoric, and that the frequent changes in the White House version could therefore be explained in all-too-human terms of lapsed memory. Daily, we were assured that "nothing illegal" had been demonstrated. Meanwhile, as the special counsel bent to his labors, it became possible to say righteously that further comment might prejudice the ongoing investigation.

As the weeks turned to months, in fact, it became plausible and even fashionable to say that the press was really the problem, what with its "feeding frenzies" and all. Garry Trudeau's fading "Doonesbury" strip, Michael Kinsley's columns in The Washington Post and The New Republic, Anthony Lewis and Frank Rich in The New York Times, David Corn in The Nation, Susan Douglas in The Progressive—the whole cultural and journalistic layer of the mushy left made it its business to change the subject from the White House to the media. (Susan Douglas outdid even Frank Rich in her proto-feminist defense of Hillary Clinton, arguing that those who attacked her did so "precisely because they Finally saw a way to undermine a woman who has always inflamed their castration anxieties." I loved that "precisely.") It is possible to give a date to the moment when journalistic and liberal masochism became the dominant mode, and when "Whitewater" became the symbolic term not for presidential untruth and double-dealing but for a press that was, allegedly or supposedly, too tough instead of too meek.

This moment came when Garrison Keillor—Mr. Mushy Left in person—was called upon to address the Radio and Television Correspondents' Association at its Washington annual dinner on April 12. Rising to second the head of state—who had already whined about the press throughout his own speech—Keillor said, to an audience increasingly complicit, "All I know is what I read in the papers, so Whitewater is a complete mystery to me."

So right there, with applause already developing among the tuxes, you had a near-perfect rendition of the White House press-office line. This scandal isn't complex because accountancy is complex or because shell games and proxies and campaign finance are complex. And it's not hard to follow because the administration cover story has been switching every 12 hours or so. It's a mystery because of the press. A wise media audience will start to snigger at itself before anyone else can, to cry before it can be hurt. This Mr. Keillor's listeners duly did. But were they ready for what was coming?

My generation strikes me as self-absorbed. You hear them at the grocery store deliberating the balsamic vinegar and the olive oils . . . and you think, These people probably subscribe to an olive-oil magazine called New Dimension. They are people with too much money and very little character, people who are all sensibility and no sense, all nostalgia and no history, the people my Aunt Eleanor used to call "a $10 haircut on a 59-cent head"—people I would call yuppie swine.

After this astounding evocation of a new class and a lost generation, Keillor paused and said, as if to dispel any ambiguity, "Whitewater is their kind of scandal. It's carbonated, and it's less about what's real than it is about perceptions." The chubby palms in the audience were getting raw with clapping by now, but Keillor wasn't quite done. He had to close by intoning, "I like this president, and I think the country does. . . . The president has been nothing but bold in bringing major divisive issues into the public forum and declaring himself on them."

Right, said the White House. It can't get any better than this. Seize the time. The day after, at a no less pompous and deferential meeting of the American Society of Newspaper Editors, the president alluded several times to Keillor's oily paean, and successfully squelched the (by now) lone doubting questioner by admitting mockingly that if asked to recall "something that happened 10, 15, 17 years ago . . . no, sir, I cannot."

So now we have the alternative Whitewater narrative, whisked by repetition into a line or series of lines that people can comprehend. But what do you have to believe in order to believe the new and revisionist version?

Do you, for a start, find yourself saying that it was all a long time ago? Vince Foster's body was discovered only last year, and the prima facie attempt to thwart the inquiry into his death, or at any rate to minimize its ramifications, was unearthed even more recently. So it's lazy to describe the Whitewater affair—which has already caused two high-level resignations from the current administration—as Jurassic.

The president alluded several times to Keillor's oily paean, and squelched the lone doubting questioner.

Do you believe that the Clintons are the target of an overhungry and overmighty media? When Mr. Foster's death occurred, the press united in terming it a tragedy and in shushing those few who had the poor taste to ask questions. Journalistic curiosity was briefly whetted by the subsequent denials, nondenials, and grudging admissions. Blaming the media for this is worse than blaming the messenger. It is blotting out the message altogether. Moreover, as you can see from the partial list of star bylines above, the press and this president have never been anywhere near an estrangement. Every journalist in Washington, New York, and Los Angeles knows how long the papers sat on the story about Bill and Paula Jones.

Do you believe that only nickel-and-dime amounts are involved in Whitewater, and in the trust funds and tax filings that Mr. Foster was working on when he died? The Clinton share of the disputed take may have been small by Boesky standards. (Or by the standards of Michael Milken, about whom Bill has been so nice lately.) But the tab that James McDougal's imploded S&L passed on to the taxpayer was more than $47 million. And the general bill for society, as a result of politicians leaping into the sack with S&L operators during that period, is larger than anyone can compute. Did you once go around saying, "It's the economy, stupid"? If so, do you still?

What of the suggestion, made most aggressively by Clinton's political adviser Paul Begala, that there is an anti-southern prejudice at work in a snobbish Washington? Anyone who remembers the Democratic primaries or the Clinton inaugural can easily recall that Bill's sturdy southern virtues were continually stressed by the pundits. He was even held to "understand" black people better, and was given a free pass when he executed a brain-damaged black man during the New Hampshire primary, thus proving that he couldn't be Willie Hortoned by anybody. Indeed, his Dixieness was an inseparable part of his winning profile as a "New Democrat," and still is.

There should from the first have been a much less uncritical scrutiny of Clinton's southern exposure, and that of his distinctly Yankee wife. Between them, it is now clear, they had the state of Arkansas pretty thoroughly franchised. "Nothing illegal," as everyone is slightly too quick to say, but fairly nifty nonetheless. And not just nifty in the dim and distant past, but right up to now and imported to Washington. What do they all have in common, these Hubbells and McLartys, these big "Webb"s and big "Mack"s and so on, this gallery of overbilling lawyers and revolving-door entrepreneurs who flicker bulkily across our screens before "recusing" themselves when inquiries begin? Why, they have in common the fact that they all shared heartily in the nexus of banking, real estate, litigation, and state bonds that linked the Jackson Stephens empire, the Tyson Foods conglomerate, and the Arkla Petroleum company to Mr. McDougal's busted thrift, Mrs. Clinton's law firm, and Mr. Clinton's Executive Mansion in Little Rock.

Take my favorite connection, and one that has escaped general notice—the connection between Dan Lasater and Patsy Thomasson. Mr. Lasater was a major Arkansas bond dealer in the 1980s, and a heavy contributor to Clinton campaigns. He showed a keen appreciation of the family-values side of doing business, finding a job for Bill's hard-to-place brother, the famous Roger. Like Roger, Mr. Lasater was fond of cocaine and was sentenced to hard time not for snorting it but for transporting it. In 1987, a year after his trouble with the narcotics laws, Lasater was hit with a $3.3 million lawsuit in connection with (why does this not surprise me?) a bankrupt savings-and-loan in Illinois. During the negotiations, the federal side was represented by Hillary Clinton and Vince Foster, who tenderly bargained the damages down to an eventual $200,000.

Nor was that Mr. Lasater's only good fortune. In his unavoidable absence owing to the cocaine matter, his firm's assets were managed by Ms. Patsy Thomasson. She must have impressed Mrs. Clinton, and perhaps Mr. Clinton too, when you remember her boss's earlier generosity at electiontimes, because she was later invited to head the White House Office of Administration. And in that sensitive capacity she entered Vince Foster's office on the night of his death and was present when the since resigned Bernard Nussbaum cleansed the place of all files relating to the Whitewater Development Corp.

Ms. Thomasson is to be questioned by the special counsel for that, and one of Lasater's companies that she headed is now under investigation by the S.E.C. in the suspicious trading of stock in a Seattle seafood company. Said company was known by insiders to be the target of a takeover bid by . . . Tyson Foods Inc., a company that kicked serious contributions into the Clinton coffers and one of whose officers held Hillary's hand when she dipped a toe into the perilous futures market. And the takeover bid was being handled by . . . the Rose Law Firm. So why do you think the Clintons picked Ms. Thomasson to come all the way to Washington with them? Because she looked like America? Because she put people first?

You can console yourself by saying that this, and the whole skein of coincidences of which it forms a thread, is "not illegal"—even though much of that remains to be proved. (And wasn't it Michael Kinsley, one of Clinton's keynote defenders, who once wisely pointed out that in politics the scandal is always what's legal?) What you can't say is that it is the promised break with "business as usual" and with the corrupt politics of the loathsome 80s.

Indeed, the Clinton-Rodham entanglement of interests in Arkansas bears the signs of direct descent from the ReaganBush epoch. There is Savings and Loan, exemplified by Mr. McDougal and Mr. Lasater. There is the Bank of Credit and Commerce International, a crooks' haven and laundry which actually found its way into the American banking market by means of a sale by Clinton-campaign banker Jackson Stephens. And there is Iran-contra, with its druggie underside. Mena airstrip, in western Arkansas, was a staging area for the contras, and various blind eyes were turned as a consequence. Janet Reno's Justice Department, with its heavily Arkansan senior layer, has been rather less than fanatically prosecutorial in mopping up after these interlocking scandals, and positively complicit in its handling of the Iraqgate arms-for-Saddam nightmare that so deeply involved the southern banking system. Ms. Reno, you will remember, was appointed to Justice on the recommendation of Hillary's brother Hugh.

This is not the promised break with "business as usual" and the corrupt politics of the 80s.

Another thing you must be prepared to overlook, if you desire to mellow out with Garrison Keillor, is the Clintons' attitude toward truth. In their repeated, near-hysterical changes of story about their money dealings, both the president and the First Lady made use of three highly suspicious tactics: rapid-fire switches of plea, sentimental blackmail, and aggressive self-pity. Clinton hid behind his dead mother for a week or two, and Hillary hid behind her unborn daughter until a change of story line was forced on her by the facts. Clinton asked us to believe that he—the king of the briefing books—had forgotten a $20,000 "loan" that amounted to more than half his governor's salary, and that this loan from Mr. McDougal had gone toward a house in Hot Springs for his mother. Hillary Clinton claimed that she had been scared off commodities trading after she found she was with child.

Who forgets his mother's house? Who forgets when she had a baby? And when caught out, the royal couple turned nasty. "This is a well-organized and well-financed attempt to undermine my husband and by extension myself, by people who have a different political agenda or have another personal and financial reason for attacking us." Thus Hillary in the White House on March 4. Does that answer all your questions? "Maybe you think I should have shut the whole federal government down and done nothing but study these things for the last two months." Thus Clinton to the newspaper editors in April. Well, no, not really, Mr. President. A straight answer couldn't possibly have taken that long.

And since the Deity is in the details, do you care that one of Hillary's portfolios was Value Partners, an exciting and profitable fund that was selling health-care stocks short as late as December 1992 and perhaps as late as May 1993, when the Clinton investments belatedly went into the blind trust that Vince Foster was working on? Or that the future First Lady's law firm helped buy 45 nursing homes in Iowa and sell them for twice their book value in 1989? Forget it. You don't want to be accused of postponing health-care reform, or of joining the well-financed attack machine, or of criticizing the First Family's blameless mothers and daughters, or of insulting Garrison Keillor's Aunt Eleanor, or of having an expensive haircut (though wasn't it Bill who brought Cristophe onto Air Force One?).

You'll have to excuse me for saying so, but there is something terminally cheap and shallow about the Clintonian style. Clinton didn't even run as an outsider until he had taken care to square the idea with every special interest in the Democratic Party. Once in Washington, he felt instantly at home with Pamela Harriman, Lloyd Bentsen, Vernon Jordan, David Gergen, Lloyd Cutler, and the rest. When it came to the smallest test of courage or loyalty—whether to Lani Guinier or to gays in the military—Bill did a fade. The only people he's always been consistent about, the only group he's been unfailingly loyal to, is the old gang from the Arkansas "business community," who include his spouse. And through his spouse, that heroic antismoker, low-cal-food campaigner, and spare-time patroness of good causes, the president has been able to veneer himself with a sheen of decaffeinated correctness. "Yuppie swine" is a phrase Keillor might have been better off avoiding.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now