Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPlagued by the celebrity tell-all and the self-justifying memoir, the stranger's description of his underwear or his orgasm, America has become almost impossible to embarrass

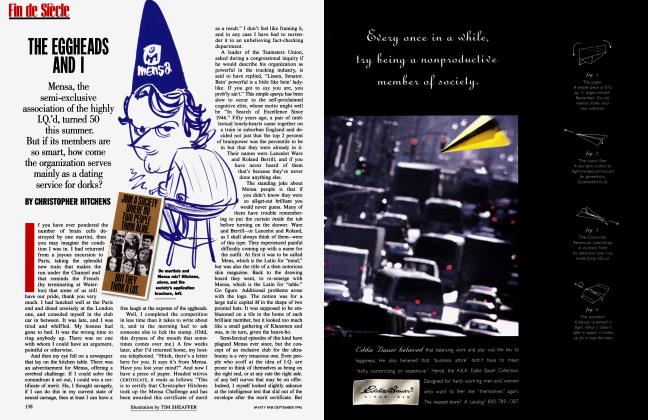

March 1996 Christopher Hitchens Philip BurkePlagued by the celebrity tell-all and the self-justifying memoir, the stranger's description of his underwear or his orgasm, America has become almost impossible to embarrass

March 1996 Christopher Hitchens Philip BurkeShame is like everything else; live with it for long enough and it becomes part of the furniture.—Salman Rushdie, Shame.

Years ago, when I worked at the New Statesman, we used to run a weekend competition. One of the most successful was an appeal for horrendously wrong advice, to be printed in a travel guide for foreign visitors to London. The results ("Do try the famous echo in the British Museum Reading Room") exceeded all expectations, and exposed a profound vein of sadism in our enlightened readers. "Please remember to shake hands with everyone else in the railway carriage before taking your own seat." "Help with the Times crossword is always appreciated by your fellow passengers." "Prostitutes may be recognized by the tins they rattle at street corners to attract custom." Every police station in London is surmounted by a blue lamp, so Frenchmen and Germans in search of adventure were directed to the "blue-light district." They were warned that those at the desk inside, being British, would at first pretend not to know what was wanted. But, with the necessary persistence, this insular reserve could be overcome.

The joke "worked" because everybody knew about that insular reserve. But what would you have to do, in this culture, to put someone in a position of such embarrassment or—a more serious word—shame? I have just seen one of those celebrity shows on television. The subject was Tonya Harding's wedding, and Tonya Harding's bridal dress. Golly, I thought. Not only was Tonya Harding once mentioned in the same breath as an attempt to maim a sporting rival, but I was once offered, at my local video store, an actual tape of the most virulently intimate parts of her previous wedding night. Yet here she is, preening on-screen and being given the most gushing commentary, looking all the time as if butter wouldn't melt in her mouth. Replace notoriety with celebrity and this is what you get.

There is a good reason the words "shameful" and "shameless" define the same conduct. You know you've behaved shamefully if you have exposed other people to needless annoyance or embarrassment. You don't know you've behaved shamelessly if you don't get this point. All societies have devised some sort of code to deal with the shameless. The English one is notorious, and is open to the charge that it nurtures hypocrisy, but is at least intelligible and easy to follow.

Resign? When did any politician or executive last offer to do that, having been caught lying to Congress or padding the payroll?

Other cultures have evolved other codes. When V. S. Naipaul made his first voyage to India—the country of his ancestors—he was struck immediately by the shocking business of people relieving themselves alfresco. India, through no fault of its own, has many more people than it has indoor plumbing units. As a consequence, Naipaul's famously fastidious nostrils acquired a near-permanent wrinkle of distaste. But this did not blunt his powers of observation. In the gorgeous scenery of Kashmir, for example, he noted the fact that Shankaracharya Hill, just outside Srinagar, is a hazard to the choosier tourist. "Large areas of its lower slopes are used as latrines," he wrote. "If you surprise a group of three women, companionably defecating, they will giggle: the shame is yours, for exposing yourself to such a scene." (My italics.)

Every society needs a way of coping with embarrassment, and in this detail we can see not the backwardness of India but rather its sophistication. A country with precious little privacy, but with a very highly ordered system of manners, has been ingenious in placing the responsibility on the voyeur. The United States invented "the comfort station" and "the rest room" and many kindred euphemisms to cope with the same sort of unpleasantness. Yet I don't like to think of what might happen if the plumbing ever broke down. You might snap on your trusty television set and see: "Today, women who go to the bathroom en masse—AND THE MEN WHO STUMBLE UPON THEM."

I don't wish to add to the ream of selfI righteous stuff that's been written I about the television of embarrassment and exposure except to say that it's difficult to apportion the shame. Who is the offender here—the sufferer baring the unsightly wound or the audience that gathers for a good long look? Not only are there infinite numbers of flashers, but they seem to pull a limitless crowd of voyeurs. One night I was stuck in some studio waiting room and watched David Letterman trying to cope while Howard Stern (enveloped in a revealing white ball gown) attempted at the top of his voice to "share" an orgasm he'd recently enjoyed. The audience was starting to bay and whinny, and things were looking bad. Letterman, who I'm sure would rather die than be accused of spoiling the fun, but who has to worry about other things too, came out of what resembled a panic and hit upon a good notion. "Too much information!" he bellowed. "Too. Much. INFORMATION."

I would very much like to popularize this rejoinder. Think of the occasions on which you could uncork it. On any given day, a perfect stranger may ring you up at dinnertime to describe a brandnew product or credit card or investment scheme. Another newcomer to your life may take the next seat on an airplane and begin to confide about his or her religion, or his or her shrink. People pull up chairs at dinner tables and launch into a description of some intestinal or uterine nightmare, and the "procedure" that brought relief from it. To all these, one could turn with a polite smile and say, "Too much information." Or one could hang up the phone with it, leaving the huckster to ponder a whole new and unfamiliar concept.

It is interesting that so much of our concept of shame is derived from Asia. I was in Northern California at the turn of the year, when a winter storm knocked out the power lines in much of the Bay Area. Pacific Gas and Electric ("A winter storm? In December?") took as long as six days to restore the current in some towns. It turned out that PG&E had been busily downsizing its repair crews, just in time for winter.

The local-newspaper correspondence was a sight to see. Almost everybody knew that in Japan corporate executives apologized when their planes crashed or their products misfired. One letter writer held up the shining example of the Tokyo phone company, which sent a bowing and scraping representative to every household after a brief outage. In California, there was no word from PG&E, and those who called the emergency number were put on indefinite hold and made to listen to a recording of Schubert's Unfinished Symphony. ("I was on hold so long," said one outraged customer, "Schubert finished the damn piece.")

In Asia, there is the concept of "face." In the United States, there is only the expression, and it comes out either as "in your face" or "Do you know what they had the face to tell me?" As Salman Rushdie says in his classic novel on the subject, which is set in a magic-realist version of Pakistan, a character may have "a high reputation as a doctor and a low reputation as a human being, a degenerate of whom it is often said that he appears to be entirely without shame, 'fellow doesn't know the meaning of the word,' as if some essential part of his education has been overlooked; or perhaps he has deliberately chosen to expunge the word from his vocabulary, lest its explosive presence there amid the memories of his past and present actions shatter him like an old pot."

An "essential part of his education." Yes. When did people decide to dispense with this? Not long ago, I saw a photograph of John Profumo bowing his head to accept a decoration from Queen Elizabeth. Profumo had been secretary of state for war in the early 1960s, and gave his name to the scandal in which he carried on with Mandy Rice-Davies and Christine Keeler—who was carrying on with a Russian spy—and told lies to the House of Commons. He was compelled to resign. So what was the decoration for? It was for many years' worth of unpublicized and unremunerated work in the slums of London's East End. Profumo, having brought disgrace upon himself and the colleagues who had trusted him, had slipped away. No celebrity book tour, no self-justifying memoir, no hiring of an image doctor. He had gone in for a bit of modest atonement instead.

And did I just use the word "resign"? What an archaic term. When did any politician or executive last offer to do that, having been caught lying to Congress or gouging a customer or padding the payroll with family members? Richard Nixon resigned, but only after he had wheedled a pardon in advance. And he went on to write numerous books and give endless interviews, in none of which—note this—did he ever offer a single word of apology or contrition for the inconvenience, if nothing else, to which he had put everybody.

The concept of shame is intimately linked to the concept of responsibility, and who wants to accept that? These days, if a public figure "accepts responsibility"—like Janet Reno disingenuously claiming it for the Waco massacre—it is only as a means of evading it. It's just one more maneuver, a tactic in the survival kit for shameless people. I think this is why so many people felt a vague sense of regret when Colin Powell declined a run for the White House. Among the things he had mentioned as motivating his initial interest was a desire to "restore a sense of shame in our society."

Observe the way in which the current White House has been doling out its W Whitewater disclosures, agreeing to "find" certain public documents only after they've turned out to already be in the possession of investigators. But is there any evidence of shame? To the contrary, there are high-level internal inquiries about why the fiasco was not better "handled." Here, shameful and shameless meet. "Who do they think they are?" and "What do they take us for?" become one and the same question.

Just as people with blowtorch breath are the ones who are keenest on thrusting their face right into yours as they, so to speak, ram home their point, so people without shame are those with the least gift of reticence. And, as with halitosis, it seems that friends will never tell you. Who can have encouraged Ms. Leona Helmsley to take a costly twopage advertisement in The New York Times Magazine? SHE KNOWS PEOPLE TALK ABOUT HER, bellowed the first page in an ecstasy of vulgarity, SHE'LL EVEN SHOW YOU WHAT THEY SAY, trumpeted the next. Of course she will. She's a raving exhibitionist.

The whole phenomenon is very well caught by the unimprovable title which O. J. Simpson gave to his self-pitying jailhouse book, I Want to Tell You. Yes, I think that's got everything. It has both of the essential ingredients of the shameless. Its entire stress is on the first person and on the present tense. Me, Me, Me and Now, Now, Now. What would it take to embarrass such a person? Do we even have such a standard anymore?

The history of shame in America is rather contradictory. In the beginning were the frontier and the pioneer, with a big stress on candor. No hypocrisy and no pretense: Sure, we did away with those Indians and those buffalo. Wanna make something of it? Yes, I'm rich and I don't care who knows it. Here's my gun—right on my belt.

But behind the wagons came the preachers and the schoolmarms and the notions of a middle class and of "respectability." Manuals on etiquette and deportment began to proliferate, for people who wished to do the right thing, or know what the right thing was. There's a hectic alternation in the national character—between the Anti-Saloon League and Hollywood Babylon—and as a consequence nobody knows where shyness and decency ought to end and shame to begin. Example: Is it kosher to ask the president about his underwear on MTV? Yes, Virginia, it is kosher to ask this particular president, because he is bursting with desire to fill you in on his briefs. Once again and all together now: TOO MUCH INFORMATION.

And when it's not too much, in our shameless society, it's too little. The shameless person is really saying, It doesn't occur to me to consider your feelings in this matter. I have a loftier responsibility, which is to myself. Thus, you need to know all about my needs and dreads and dreams and recent troubles and even my underwear, even though we have barely been introduced. But you are not entitled to any explanation or apology about why my company stiffed you/why my government broke its promise/why my children wiped their noses on your sleeve while I looked fondly on/why my dog can do what the hell it likes in the park/why my lobbying firm boasts of its "clout" instead of being decently modest about the fact/why my candidate doesn't give a **** what you think because it hasn't yet "impacted" his approval ratings.

"Shame, dear reader," wrote Rushdie, "is not the exclusive property of the East." Nor is it. But there are times when it might be right and proper to envy and emulate the Japanese.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now