Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBENEATH A MOCKING SKY

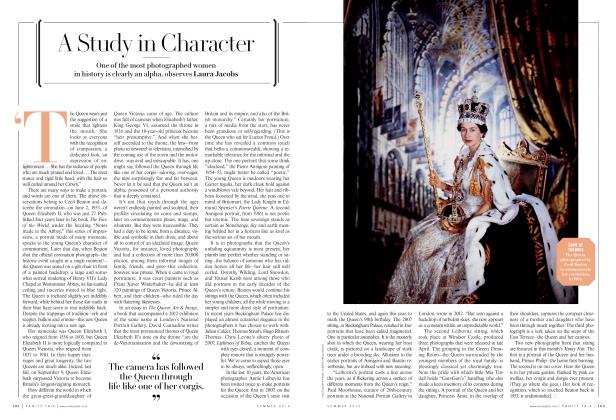

Death by aeroplane: an excerpt fromStaring at the Sun,the new novel by JULIAN BARNES, author ofFlaubert's Parrot. (Warning: not to be read in-flight)

Flabert's Parrot.

Aeroplanes—in homage to Prosser she went on calling them aeroplanes long after they had been shortened to planes—never frightened Jean. She didn't need to cram music into her ears through a plastic tube, order stout little bottles of spirits, or probe a heel beneath her seat for the life jacket. Once she had dropped several thousand feet over the Mediterranean; once her aeroplane had turned back to Madrid and circlingly burned up fuel for two hours; once, landing from the sea at Hong Kong, they had bounced along the runway like a skimming stone—as if they really had put down on water. But on each occasion Jean had merely withdrawn into thought.

Gregory—studious, melancholy, methodical Gregory—did the worrying for her. When he took Jean to the airport, he would smell the kerosene and imagine charred flesh; he would listen to the engines at takeoff and hear only the pure voice of hysteria. In the old days, it had been hell, not death, that was feared, and artists had elaborated such fears in panoramas of pain. Now there was no hell, fear was known to be finite, and the engineers had taken over. There had been no deliberate plan, but in elaborating the aeroplane, and in doing all they could to calm those who flew in it, they had created, it seemed to Gregory, the most infernal conditions in which to die.

Ignorance, that was the first aspect of the engineers' modem form of death. It was well known that if anything went wrong with an aeroplane the passengers were told no more than they needed to know. If a wing fell off, the calmvoiced Scottish captain would tell you that the soft-drinks dispenser was malfunctioning, and this was why he had decided to lose height in a spin without first warning his cargo to put on their seat belts. You would be lied to even as you died.

Ignorance, but also certainty. As you fell 30,000 feet, whether towards land or water (though water, from that height, would be the same as concrete), you knew that when you hit the ground you would die: you would die, in fact, several hundred times over. Even before the nuclear bomb, the aeroplane had introduced the concept of overkill: as you struck the ground, the jolt from your seat belt would induce a fatal heart attack; then fire would bum you to death all over again; then an explosion would scatter you over some forlorn hillside; and then, as rescue teams searched ploddingly for you beneath a mocking sky, the million burned, exploded, cardiac-arrested bits of you would die once more from exposure. This was normal; this was certain. Certainty ought to cancel out ignorance, but it didn't; indeed, the aeroplane had reversed the established relation between these two concepts. In a traditional death the doctor at your bedside could tell you what was wrong, but would rarely predict the final outcome: even the most skeptical sawbones had seen a few miracle recoveries. So you were certain of the cause but ignorant of the outcome. Now you were ignorant of the cause but certain of the outcome. This didn't strike Gregory as progress.

BENEATH AMOCKING SKY

Next, enclosure. Do we not all fear the claustrophobia of the coffin? The aeroplane recognized and magnified this image. Gregory thought of pilots in the First World War, the wind playing tunes as it whistled through their struts; of pilots in the Second World War, doing a victory roll and embracing as they did both the skies and the earth. Those fliers touched nature as they moved; and when the plywood biplane peeled apart under sudden air pressure, when the Hurricane, excreting the black smoke of its own obituary, wailed down into some damp cornfield, there was a chance—just a chance—that these endings were in some degree appropriate: the flier had left the earth and was now being called back. But in a passenger plane with mean windows? How could you feel the dulcet consolation of nature's cycle as you sat there with your shoes off, unable to see out, with your frightened eye everywhere assailed by garish seat covers? The surroundings were simply not up to it.

And the surroundings included the fourth thing, the company. How would we most like to die? It is not an easy question, but to Gregory there seemed various possibilities: surrounded by your family, with or without a priest—this was the traditional posture, death as a kind of supreme Christmas dinner. Or surrounded by gentle, quiet, attentive medical staff, a surrogate family who knew about relieving pain and could be counted on not to make a fuss. Third, perhaps, if your family failed and you had not merited the hospital, you might prefer to die at home, in a favorite chair, with an animal for company, or a fire, or a collection of photographs, or a strong drink. But who would choose to die in the company of 350 strangers, not all of whom might behave well? A soldier might charge to a certain death—across the mud, across the veld— but he would die with those he knew, 350 men whose presence would induce stoicism as he was sliced in half by machine-gun fire. But these strangers? There would be screaming, that much you could rely on. To die listening to your own screams was bad enough; to die listening to the screams of others was part of this new engineers' hell. Gregory imagined himself in a field with a buzzing dot high above. They could all be screaming inside, all 350 of them; yet the normal hysteria of the engines would drown everything.

Screaming, enclosed, ignorant, and certain. And in addition, it was all so domestic. This was the fifth and final element in the triumph of the engineers. You died with a headrest and an antimacassar. You died with a little plastic fold-down table whose surface bore a circular indentation so that your coffee cup would be held safely. You died with overhead luggage racks and little plastic blinds to pull down over the mean windows. You died with supermarket girls waiting on you. You died with soft furnishings designed to make you feel jolly. You died stubbing out your cigarette in the ashtray on your armrest. You died watching a film from which most of the sexual content had been deleted. You died with the razor towel you had stolen still in your shaving kit. You died after being told that you had made good time thanks to following winds and were now ahead of schedule. You were indeed: way ahead of schedule. You died with your neighbor's drink spilling over you. You died domestically; yet not in your own home, in someone else's, someone whom you never met before and who had invited a load of strangers round. How, in such circumstances, could you see your own extinction as something tragic, or even important, or even relevant? It would be a death which mocked you.

If a wing fell off, the calm-voiced Scottish captain would tell you that the soft-drinks dispenser was malfunctioning.x

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now