Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHE-E-ERE'S MELVYN!

Melvyn Bragg is Britain s prime-time polymath, and a best-selling author. And the culturati can't stop talking about him

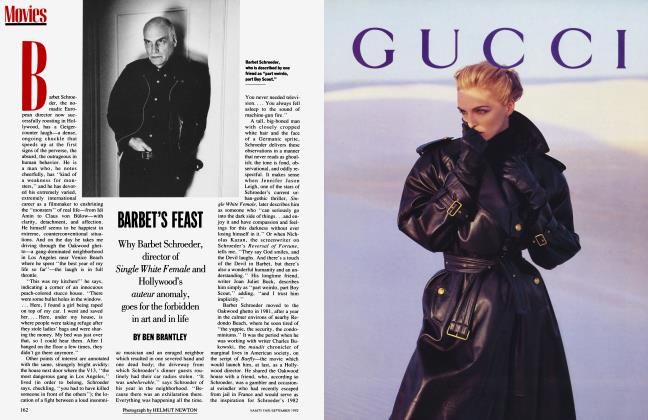

BEN BRANTLEY

Letter from London

It's one of those not uncommon days on which Melvyn Bragg is feeling, as he puts it, like "this ludicrous grasshopper figure," hopping, with abrupt shifts of focus, among a series of "B-movie conversations." We're racing through the sunny, Thames-side offices of London Weekend Television, where Bragg is controller of the arts and host, editor, and chief interviewer of LWT's enduringly popular arts program, The South Bank Show. On his way to a voice-over taping session in a studio downstairs, for a documentary on the New York painter Roy Lichtenstein, Bragg has been stopping by the desks of assorted researchers and producers on his team to fire off questions with the brisk, patented-seeming jocularity common to creatures of the medium. Stepping into the elevator, he says, in a characteristic leap from selfimportance to self-parody, "It's like I'm Victor Mature playing me."

Though The South Bank Show is now in its thirteenth year, Bragg has probably been the focus of as many interviews as he's produced, and he's wont to swing suddenly into a mode in which Melvyn Bragg seems to be looking at Melvyn Bragg, anticipating and answering the questions and criticism of an eternal, invisible horde of observers. "Yes, he certainly has a tendency to the defensive, pre-emptive strike," says the writer Julian Barnes, a friend of Bragg's who remembers interviewing him in the late seventies. The posture is perhaps inevitable. In England, his fame far exceeds that of his closest American equivalent, Bill Moyers, in the States, and it's difficult to spend much time in London without addressing the fact of this fifty-year-old culture maven, whose, round, handsomely earnest face, topped by a carefully combed mop of Beatlelike hair, appears on telly screens most Sunday nights, presenting an audience of 2.5 million with hour-long profiles of such disparate figures as Paul McCartney, Paul Bowles, Spike Lee, and Francis Bacon. His much-imitated voice—a folksy, knowing blend of nasal, Lake District mateyness and BBC urbanity— chats on further about all things cultural on the comparably popular Start of the Week radio show, which he hosts. His fourteenth novel, A Time to Dance, will be released here this month by Little, Brown; the sexually detailed story of a love affair between a fifty-four-year-old bank manager and an eighteen-yearold working-class lass, it is a best-seller in England, choicely positioned in the windows of the book chains. The musical he scripted, The Hired Man, ran for eleven months in the West End. He regularly shows up in the grayer dailies (for his steadfast championing of the subsidized arts), the tabloids (which breathed heavily over his alleged extramarital relationship with a former girlfriend of Prince Charles's), and the lampoons, such as Private. Eye and TV's Spitting Image, which features him as a cocky, adenoidal puppet. Last season, you could even watch Melvyn Bragg sending up Melvyn Bragg, in a television parody of the classic South Bank-style arts interview.

As British television hosts go, Bragg presents a mild-mannered persona, yet he tends to draw lightning. At a publishing party in 1989, a man who had never met Bragg, but said he'd always hated him on the small screen, physically attacked him, wrestling him to the ground. ("Quite a nice chap," Bragg says wistfully when I bring up the incident. "He was drunk and didn't know what he was doing. Actually, he was a great admirer.") Mention Bragg's name at a London dinner or cocktail party and you're apt to elicit extreme opinions— ranging from reverence to ridicule—and a spate of rumors: Was he offered the top job at a rival TV station? Will he be made minister of the arts if the Labour government gets in? "Once you become Melvyn-conscious, it's difficult to get him out of your consciousness," says Bragg's friend Bryan Appleyard, a cultural critic for the London Times. "You run into him everywhere, and everyone talks to you about him; he's all-pervasive." A less admiring Bragg watcher compares him to the blancmanges, the extraterrestrial custards that come to devour Britain on Monty Python, and says, "England is such a small place, and he's monopolized everything." Nearly everyone concedes his likability, intelligence, his inestimable value as a promoter of the arts; what they can't seem to get over is his very multifariousness. "He's a man who's constantly juggling with all the balls and doesn't want any of the balls to fall down," says Andy Harris, a television director who has worked with Bragg on South Bank. "By and large, he's been brilliant at keeping them all in the air. What would happen if they did start tumbling down I don't know."

Even in the few hours I spend with Bragg one Friday, the juggling act is in conspicuous spin. In the morning, he's at a BBC radio studio, raffishly discussing, by phone, the prurient response to A Time to Dance ("If you write in the first person [about sex], people feel it's bound to be you...it's bound to be nudge, nudge, wink, wink") with an interviewer in Oxford. He lunches at the Ritz with his accountant ("a man who told me how much money I haven't got, and I wound up paying"). Back in his book-glutted, award-studded comer office at LWT, as we settle in for our interview, he calls out to his secretary, "Do you have a bottle of really, really good white wine? And can you get it really, really cold in half an hour?" The phone rings. There's a call from his lawyer, about problems in renewing the broadcast franchise for the Border Television station, of which Bragg is the chairman, and another, more mysterious call from someone who's been in touch with a South Bank Show subject who is to be interviewed that weekend.

"Is he looking forward to it?" Bragg says into the receiver, lowering his voice. "Well, you knew he'd be nervous . . .He's going to be terrific. . .All I want him to do is, I want the first magazine of film to be kind of human. Because I think the G.B.P., the Great British Public, most of whom will tune in to see him The Man, will just want to know, What's life like?...They know him as a principle, they know him as an issue, but they don't know him as a chap...I really would think I've gained something for him if, around the place, the next day, people are saying, 'I saw the [pause] guy, and he's a nice bloke, isn't he? Yeah, yeah, a nice chap, really.' "

The unidentified guy, I will learn the following Monday, is Salman Rushdie, whom Bragg has secured for the author's first television interview since he went into hiding in February 1989. The interview, pegged to the publication of Rushdie's Haroun and the Sea of Stories, is to be conducted under an elaborate cloak of security precautions, and the crew will not be told where they are going or who is being interviewed. "When I get to know you better, if that ever happens," Bragg will say to me the following week, "I will tell you where [the interview took place], and then I think your hair will fall out." On this particular Friday, the prospect of the encounter has brought a palpable edge of anxiety to Bragg's trademark affability. "I'm rather embarrassed at having this thing hover around when you're doing an interview," he says, adding quickly, "and I'm not being silly."

"Once you become Melvyn-conscious, you run into him everywhere, and everyone talks to you about him."

Though Bragg grudgingly concedes that being a novelist is the most cherished of his many professional incarnations, he seems ill at ease when he talks about his writing. Midway through the interview, he asks if we could discuss his television work instead. "I mean, the writing..." He trails off wearily and then gestures toward a chart on the wall with the handwritten lineup of the new season of South Bank shows. "It's just that with television it's all organized."

Bragg, his friends will tell you, is above all an organized man, someone who, as British film producer David Puttnam puts it, "is able to apportion his life very intelligently." He schedules his television workweek with meticulous rigor, "cramming everything I can into a short time here so I'll have more days to write." This controlling discipline extends to his personal habits. Though he is known to tie one on during his regular country outings with his staff, he designates the first week of every month as his "nondrinking" week. (One TV producer told me he'd learned to pitch story ideas to Bragg on the evenings he terminates these periods of abstinence.) "One of the things that thrills me about Melvyn is he could've easily allowed himself to sink into a booze problem," says Puttnam, "and he's been brilliantly disciplined about it." He divides his domestic life, with similar efficiency, between London—where he shares a £1 million house in Hampstead with his wife, Cate, a television producer and writer, and their two children—and his native Cumbria, in the Lake District, which is the setting for most of his novels and the place where he now writes the major part of them. He floats brightly through the urbane world of London's glitterati and loves solitary, mindclearing walks through the Cumbrian hills; is a bon vivant, friends say, of essentially conservative temperament and a staunch supporter of the Labour Party. "He's quite good on his social tourism," says the BBC's Jamie Muir, a former producer for South Bank. "You could find him in a pub or the Athenaeum. I think he quite likes the fact that he can sort of rise and fall, like a fishing float."

Bragg himself sees nothing peculiar in his ability to switch psychological and professional channels. It is, he says, the story of his life. He grew up in workingclass Wigton, the son of owners of a pub called the Black-a-moor, an "extremely noisy and quite, for a while, violent" place. "I used to be up on my own upstairs, working to try to get the scholarships, while all that row was going on downstairs, and I could cut off. I mean, in a sense to my detriment, I haven't found it ever too difficult to cut from one thing into another."

This penchant reached its most extreme, and disturbing, form in early adolescence, when Bragg began to have split-consciousness experiences, in which his mind would leave his body, phenomena which recurred over a period of four years. It was nothing, he says, he could tell anyone about. "We didn't talk much in our household; we certainly didn't talk about our mental condition." He became, for a period, a devout Christian, studied assiduously, got a scholarship to Oxford—where, he estimates, students from his social stratum represented less than half a percent—and graduated with a second in modem history.

He then got a traineeship with the BBC and was soon producing literary and arts documentaries, under the aegis of Sir Huw Wheldon, the fabled czar of cultural television. He published his first novel, For Want of a Nail, the story of the brutal coming-of-age of a boy in Cumbria and the result of five years' labor, in 1965, evoking critical acclaim and comparisons to Lawrence and Hardy. He withdrew from the BBC to concentrate on fiction, augmenting his income with freelance television work and screenplays for such films as Karel Reisz's Isadora and Ken Russell's The Music Lovers.

In his early twenties, he married a Frenchwoman six years his senior, Lisa Roche, the child of the rector of the Sorbonne, with whom he had a daughter. She was, by all accounts, a beautiful woman of acute intellect (she published two novels in English) and severe mental instability. "A bit like Sylvia Plath," says Bragg. "We led a particularly intense life." By the late sixties, there were more split-mind occurrences, and Bragg began to see a psychiatrist. In 1971 his wife committed suicide, ushering in, Bragg says, a "broken-backed, broken-minded" period that would last for more than a decade. ' 'That completely fucked me up. I went broke. I didn't know whether I was coming or going or if it was Wednesday or Tuesday for a very long time. I was all over the place."

Though he continued to write, prolifically—"actually to prove to myself that I was alive"—he feels that his novels from that time are weak, that he was "treading water." He married Cate Haste in 1973, and became increasingly involved in television again, most notably as the host of a books show. He found it was work "in which you don't touch that part of yourself which is susceptible to depression. . .it's a powerful anesthetic."

When he launched The South Bank Show, in 1978, he had a clear sense of the direction in which he wanted to take it: away from "ego-driven" arts television, in which you learned more about the director than about the subject ("They all wanted to be Ken Russell"), and toward a documentary form that would reflect, as precisely as possible, the point of view of the artist being profiled. He also decided to expand the traditional scope of arts programs, emphasizing both television and theatrical dramatists, rock as well as classical musicians. The show has drawn fire for his choice of subjects, its increasing use of cinematic dramatization of scenes from books, and its lack of a detached critical perspective. (The two opening shows of this season, on the pop singer George Michael and Peter Ackroyd's controversial biography of Charles Dickens, were roundly chided by the media pundits as mere P.R. vehicles.) But the series is habitually more praised than panned and remains, as the Times's Bryan Appleyard puts it, "the standard by which other arts programs in England are judged."

It is now impossible to read his fiction without looking for autobiographical clues.

Bragg defends the noncritical posture of the program, saying he feels the questions asked of those interviewed form in themselves an implicit critique, and adds that he believes he's creating a living archive of today's artists which will be invaluable to future historians. "I've absolutely no doubt that the work of some of these guys in the office [who direct the documentaries] will last longer than almost any contemporary novelist and almost any contemporary featurefilm maker."

His active role in the shows—which are actually made by a varying team of researchers, producers, and directors— is to approve the initial list of subjects and oversee the final edits, and also, in many cases, to appear on-screen as the man who asks the questions, as a comfortingly familiar, telegenic bridge, suggests Bragg, for viewers who might be put off by the more avant-garde subject matter. Though he says his goal is to remain inconspicuous on-camera, the documentaries have often played memorably on his presence: a Pinteresque interview with Harold Pinter, in which the playwright's laconic nonresponses were followed by cuts to Bragg saying things like "I knew I shouldn't have asked that"; a surreal, intense conversation in a dark screening room with Martin Scorsese, when Bragg had a fever of 102 degrees and the director was suffering from asthma; a wine-drenched lunch with the painter Francis Bacon, in which interviewer and interviewee philosophized boozily on the nature of fantasy and reality.

Envious colleagues see in Bragg a greater degree of vanity than the producer is willing to admit to. ("It was very well known," says one associate, "that if there weren't a certain number of good-looking shots of Melvyn he'd basically insist you put them in.") His staff, I was told, is "obsessed" with him, given to endless after-hours discussions of his quirks and motives, his temperamental flare-ups, and his tendency to conclude an argument by reminding people "of just how long he's been working in TV." Yet even a former employee who characterized him as a "megalomaniac" ended by saying—as nearly everyone does, in some form—"I feel a sort of protective fondness for him." He is universally credited as a keen-eyed editor and a loyal, fair employer, who promotes those who won't promote themselves, if he sees talent in them.

He is also widely described as a man whose political ken stretches far beyond the immediate bailiwick of The South Bank Show. A researcher remembers discussing her professional future with him and thinking, "God, he sees the whole chessboard. In this conversation, he's thinking three moves ahead, and I'm working out the next one." He is legendary for his information-ferreting phone calls to his network of friends in journalism, politics, and the arts. Bryan Appleyard recalls that, after interviewing a broadcast executive for the Times, he received a call from Bragg telling him "I'd got it precisely right. He then told me things I hadn't known. He knew exactly what this man's game plan must be." Describing Bragg as "a brilliant strategist," he adds, "Because he has so many irons in the fire, I wouldn't know from one minute to the next what exactly was motivating him. That's the trouble with Melvyn: he has so many aspects of his life and meets so many people and is known by so many people, you don't fully know what pressures are involved. Anything could happen with Melvyn. Everyone talks of it as a joke, but you often see sketches in which he's become Lord Bragg of Wigton. There's something sort of inevitable about all this."

Everyone—including Bragg—seems to think he has a political future. ''There is the general feeling that if Labour gets in, I'm supposed to be offered something to run the arts," says Bragg coyly. ''That's the kind of gossip which might have a certain truth in it."

As Bragg's fame has blossomed, his skin, it would seem, has grown thinner. David Puttnam remembers meeting Bragg in the sixties and being impressed by how ''enormously confident" he was. In the succeeding years, says Puttnam, "the certitude has had the edges rubbed off it. ... I find him more sensitive, more questioning." Though Bragg can be very funny in deflating his own pretensions, he tends to get edgy when other people do it.

It is as a novelist that he appears to be the most vulnerable. Throughout our conversation, he himself brings up critics' objections to his recent works. ("I got criticized quite a bit by some critics in America," he says of his financially successful biography of Richard Burton. "I thought they missed the point of why I wrote it. Of course, I would think that.") And he says "I vaguely regret" becoming a TV personality, since "one's stock as a novelist plummeted." While his on-screen ubiquity has undoubtedly increased his commercial value—his last three books have all been best-sellers—it is now impossible to read his fiction, ambitious though it may be, in England without looking for autobiographical clues, as if he were Joan Collins.

Accordingly, when A Time to Dance was released last spring, there was a lot of lascivious lip smacking and hoo-haing. Here, after all, was a portrait of a man roughly Bragg's age in sexual thrall to an eighteen-year-old girl, whose feverish copulations were described with purple precision. Writing in The Sunday Times, Harvey Porlock commented on "the sight of reviewers oohing and aahing at the prospect of smartypants Melvyn apparently dropping his boxer shorts for public inspection. Any suggestion that the novel might bear discussion as a literary construct, or that the quinquagenarian satyr might be a fiction creation rather than a gossamer-thin bit of autobiography, was grudgingly advanced, if at all." Bragg himself says, as he said repeatedly to other interviewers, that of course he's known "sexual obsession," but that the parallel stops there. His intention was simply to write accurately and honestly about eroticism, which has "been in such a mess for so long in literature." His main regret about the work, he adds, is "I wish actually it was stronger; I should have made it even more primitive, even more violent, really."

It's a fashionable theory in literary London these days that Bragg has undercut his early potential as a writer, that he

is, as one editor puts it, "a man who could be talked about in the same breath as the great English novelists, and in the end he's been sucked up by the most insidious pirate of all, television fame." On the other hand, he has continued to receive favorable reviews from such critics as Peter Ackroyd and Auberon Waugh.

Bragg admits that, though "I've given the show everything, I don't know that I've given my writing everything I could give it." He adds he's developed "exceptionally slowly," partly from being caught "in this sort of arts furnace that I've been in for the last fourteen years, and addressing oneself to these people year in, year out, week in, week out. . ..

"I feel I've lacked a sort of personal ambition as a novelist that I know a lot of other novelists have," he continues.

' 'I think I've got it, but I think I've buried

it. . .1 don't know when, sometime in the early seventies. Maybe to do with the death of my wife, maybe to do with being battered around so much by myself. ' '

Still, in spite of talk of his launching yet another TV program and the prospect of a Cabinet post, he remains firmly committed to writing, and has at least two new literary projects in mind. He thinks that in recent years "I've become more adventurous and demanding than I've been since the first couple of books," that it's time "I said what I meant in fiction."

He speaks of what he sees as the novel's essential function. "I think all of us are more than disappointed, I mean deeply melancholy, that we only have a certain life," says Bragg, a man who's run through an exhausting number of incarnations. "And the older we get, that life becomes narrower.... I do believe that a good novel is a takeover bid for both the writer and the reader. And that takeover is a different life." □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now