Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Older the Better?

Vintage Point

JOEL L. FLEISHMAN on the California-Bordeaux aging controversy

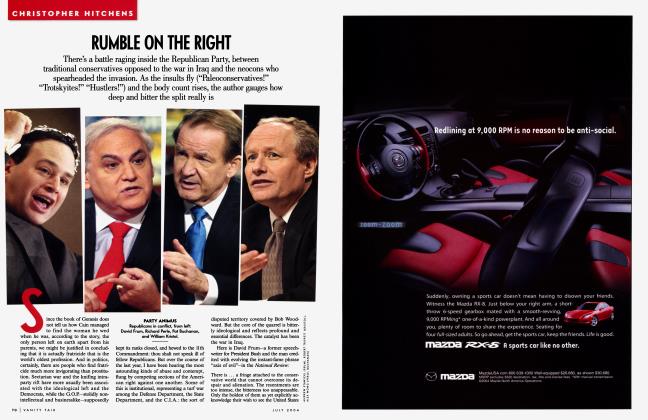

Early this year, in his usual space in the New York Times, Frank Prial took California wine-maker William Hill to task for comparatively tasting Hill's Cabernets against Bordeaux first growths. Prial claimed it was "particularly inappropriate to match early-developing California wines with slow-maturing French ones." This prompted a long rebuttal from Hill in a wine magazine, and another column from Prial appeared in the Times, but neither did much to clarify things. Prial contends that in the various public shoot-outs between Bordeaux and Cabernets the latter, with their "ingenuous, mouth-filling flavors and heady, winy aromas," will "invariably overwhelm the more subtle, less aggressive Bordeaux wines." So far, so good. But then comes the dagger. Prial goes on: "Mr. Hill's wines [and by implication most, if not all, California Cabernets] may. . .improve with age, but not much. Those he used in this most recent tasting are ready to drink."

The truth is, however, that fine California wines, including Hill's, do age, and as they age they taste increasingly richer and riper. Moreover, it is not only when young—that is, on first release, near the vintage year—that California wines generally taste better than Bordeaux of equivalent age. In my experience, they continue to do so for about a decade. There are already many Cabernets from the 1970s that are deliciously ripe—indeed at their peak— right now. All of these taste much richer than the Bordeaux from that period, and most of them possess the backbone of acids that gives any fine wine its kick. I would, for example, confidently pit the 1977 Conn Creek, Villa Mt. Eden, or Heitz Bella Oaks against most Bordeaux from the 1970s and even 1960s, except for 1961 and 1962. Those 1977 Cabernets have a generosity of ripe flavor attained only by the greatest Bordeaux in the greatest vintages, and only when they are ripe. The Cabernets are, almost without exception, much more satisfying wines than the already ripe lesser Bordeaux vintages of 1980, 1976, 1974, and 1971—even the 1979. Unless I am mistaken, however—and it is too soon to be certain—the Californians of 1977 (not, I should stress, thought to be as great a year in California as 1968, 1970, 1974, or 1978) will have begun to decline when the great Bordeaux vintages of 1978, 1975, 1970, and 1966 open up fully, if indeed they ever do.

That is, of course, the crux of this matter. There really isn't any doubt that California Cabernets of virtually all years do ripen and become gloriously mature after eight to ten years. Nor is there any doubt that Bordeaux reds in the great years typically take at least double that time to achieve the same degree of ripeness. But, for the bulk of premium California Cabernets made in the last fifteen years, we haven't had time to discover whether they will taste as delicious in 2010 as the 1945 or 1953 Bordeaux taste today.

Why is there this difference between Bordeaux and California? I suspect that it has to do mainly with the different amounts of sunshine in the two regions. The intense California sun may well work to concentrate and draw out the fruit flavors so that they show to great advantage for ten to fifteen years and then dry out. In only two of the last twenty-five vintages has the Bordeaux sun been strong enough to concentrate sufficient sugar in the grapes to produce the level of alcohol necessary for good wine. The weaker, more diffuse sun may well leave grape flavors to ripen in a more gradual fashion.

Ideally, one would buy California Cabernets on release and store them in a cool environment for eight to ten years before drinking. Most wine lovers, however, do not have sufficient or proper storage for any sizable number of cases. Unlike the practice in Bordeaux, where some chateaux and negotiants routinely hold back a substantial percentage of each vintage for release nearer to the time of ripeness, the California winemakers, most of whom have been in business for less than fifteen years, have been unable, until now, to afford the heavy costs of huge inventories of older wines. With the financial stability that has come with growing markets for their wines, and aided by recently declining interest rates, a number of California wine-makers are beginning systematically to hold back for future sale some portion of their output. Trefethen, for example, has announced its "Library Selection," rereleases of older Chardonnays and Cabernets with a different label and, of course, a higher price than on first release. Without giving the rereleases a new designation, Heitz and Raymond are doing likewise. Joseph Phelps is treating its excellent Cabernets from the mid-1970s and early '80s in a similar fashion. Mayacamas has practiced continuous release since the early seventies.

Anyone with doubts about the comparative virtues of young and old California wines should submit themselves to the test. Try a case of 1975 Joseph Phelps Cabernet, either the less expensive Napa Valley ($435) or the extremely rare Eisele ($745), and see for yourself. Other Cabernets which I recommend with enthusiasm are the 1977 Heitz Bella Oaks ($432), the 1977 Raymond ($240) or 1978 ($216), and the 1980 Trefethen (approximately $240).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now