Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

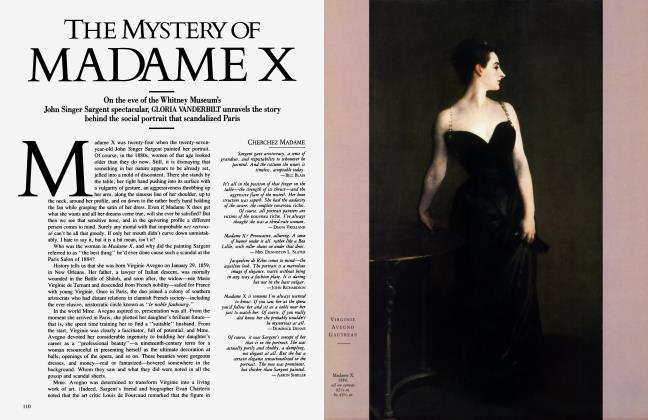

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE BIG STARE

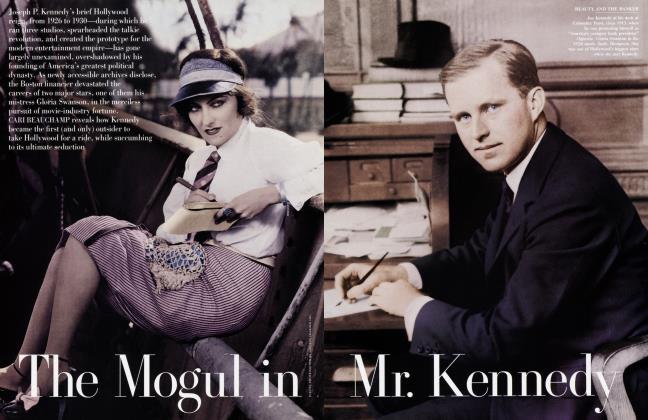

He's Cocteau in a cowboy hat. He's Warhol in a brick-wall suit. And his second movie is just out. David Byrne talks heads with JAMES WOLCOTT.

David Byme is a tough bird to figure. I've always found him polite, sociable, funny, willing to go with the moment (I once saw him swung through the air by a tall admirer as if lifted by a tornado—"Whoa!" he yelled in a kiddie voice, "whoa!"), and yet always a shade preoccupied... not quite there. Bom in Scotland in 1952, Byme was raised in the Baltimore, Maryland, area (as I was), and yet I can hear in his voice no trace of a Maryland accent. He seems completely deracinated, the product of a wacky generic suburb, or a John Waters movie set without sleaze. In photographs, even his parents appear to be props, like statues you'd pick out to go with the lawn furniture. Perhaps this deracination is what has allowed Byme to adapt his alien form to every context. His career is a series of visitations.

Byme is Andy Warhol without desiccation. When the albino goblin peered into the mirror in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, cataloguing his essences, he noted "the perfected otherness, the wispiness, the shadowy, voyeuristic, vaguely sinister aura, the pale, soft-spoken magical presence, the skin and bones..." The skeletal me! Byme too has perfected his otherness, powdered his aura with ambiguity, polished to a rich marble gloss his big stare. But his is not a death mask marked by history and erosion. After a decade-plus of shaking his tail feathers as chief wahoo of Talking Heads, Byme has entered his top-value prime. He's an iconic doodad; he could be placed on exhibition within white walls. Byrne's face is cool, detached, pantomimic. His black hair is flecked with Art Deco silver. His clothes hang casual loose on his hat-tree frame. Yet there are still dance rhythms spidering up those loose sleeves, along the slender stem of his flamingo neck. He may have inherited his cool absorption from Warhol, but his genius for discombobulation is his very own groove-thang. With the Heads, Byme located the lyrical center of his spaz attack—he turned his jitters into jubilation. And over the last few years he's collaborated with such postmodern Druids as Twyla Tharp, Robert Wilson, and Brian Eno.

As director of his first feature film, True Stories (the witty trompe l'oeil costumes for its shopping-mall fashion-show sequence were designed by his date-mate, Adelle Lutz), Byme has become both visual artist and musical composer, catalyst and controller, subject and object, seer and seen. He's watching us watch him. He's working both sides of the big stare.

I first saw David Byme get buggy during the punk jihad of 1975-76. Such nights! As a student at the Rhode Island School of Design, Byme rubbed antennae with Chris Frantz and Frantz's college pash, Tina Weymouth. To create clever art with maximum outreach, they later formed a band and moved to New York City. Taking their name from TV jargon, Talking Heads shared a cruddy loft on Chrystie Street in lower Manhattan that was but a mere gunshot away from a former bikers' bar called CBGB. On the Bowery, the club was the dirty cradle of that squalling bastard called punk. The things that went on there. Saliva shot like sea spray across the tiny stage as every angry face became a spitting fist. Stiv Bators of the Dead Boys urinated into a construction worker's hard hat and lapped up his own vomit. Another lead singer messed with razor blades onstage and staggered to the street with blood-streaming arms. ("Very Greek," a voice behind me commented.) And into this subway car to hell Talking Heads would pad in their alligator shirts, their angel-cake faces innocent of knife scars and puncture holes. (Safety pins were very in then.)

Byrnes movie is intended to mutate between what he calls the "eye candy" of rock video and the more traditional turkey stuffing of conventional narrative film.

They provided a musical contrast as well. The first time I saw a Talking Heads gig at CBGB, they followed those punk fundamentalists the Ramones, who wore black leather jackets and broke the land-speed record for fast sets by playing twelve hilarious, butch songs in just under twenty minutes, all of them executed with karate-chop chords. By contrast, the Heads seemed tentative, ricky-tick. Frantz on skins maintained a solid thud, but Byme worried and scratched at his guitar as Weymouth, armed with an oversize bass, studied him with a swiveled head. And yet even with their Me-decade chill of emotional remove, Byme's lyrics had a witty dart and surprise ("Psycho Killer, qu'est-ce que c'est?"), a mosquito's persistence. The Heads' music took on a peculiarly catchy stop-and-go quality, typified by their cover version of the bubble-gum hit "1-2-3 Red Light." In time the band's sound acquired muscle definition, and Byme's songs took on larger contours, extended drive. Where other punk-scene bands settled for snot, Talking Heads were logical, musicianly. And onstage Byme began to wiggle his goosey behind.

That set off other doubts, however. With his herkyjerky moves and strangled voice, Byme, it was suspected, might follow in the goofy footsteps of the ever boyish Jonathan Richman, who would stroll down the urinous aisle of CBGB, treating us to endless choruses of "Ice Cream Man." (Richman was the founder of an influential group called the Modem Lovers, whose keyboard player—Jerry Harrison—later became a Talking Head.) That is, Byme might surrender his edge and become a novelty act, a pet eccentric. But instead a momentous thing happened to David Byme. He found his gushing soul.

Soul is an iffy word, perhaps. It is commonly agreed to reside in the rocking gut of B. B. King, the church-tower chest of Aretha Franklin, even the dusty lungs of Willie Nelson. But in the big stare of a preppy aesthete like David Byme? Get real. Yet there was soul on the thin meat of Byme's chicken bones. He learned to express yearning instead of petulance; he lost his robot clank; he began to crave a spiritual dousing. Once he had shaken some of the fidgets from his system, the wimp hesitations of "1-2-3 Red Light" made way for the joyous, gospel plunge of A1 Green's "Take Me to the River" (another cover, and the Heads' first popular hit). By the time the Heads emerged in 1980 from the Sensurround smoke and crush of Fear of Music and into the layered intricacies of Remain in Light, they had achieved an exalted breakthrough in black-white urban-folk individual-tribal fusion. Their love of black music was part of that exaltation. More important, Talking Heads were—and are—one of the few white groups that could work with black musicians and not come across as slumming or patronizing. This rapport cooked in their concert film, Stop Making Sense, which wasn't technopop or trippy, as one might have expected from RISD students, but a communal sweat bath. Directed by Jonathan Demme, Stop Making Sense put Byme's gaudy soul on parade. He ran laps, danced a pas de deux with a lamp, lumbered out in a Big Suit, let a little happy light reflect in his big stare. He seemed baptized— reborn—in the film's warm, funky broth.

It was on the Stop Making Sense tour that David Byme began gathering twigs for True Stories. Set in a small nutty Texas town celebrating the state's sesquicentennial, True Stories was inspired by weird items Byme clipped from tacky supermarket tabloids specializing in "news" about freaks, geeks, and blinking lights. (u.F.o.s SIGHTED OVER ELVIS'S GRAVE is one of the classic headlines.) Posted on the recording-studio door in San Francisco where Byme finessed the sound and sync of True Stories' music tracks was a Xeroxed sheet of such oddities, including one about three people being treated at a psychiatric hospital for trying to emulate Jesus walking on water: ' 'They were in a trance and had apparently been chanting, 'Baby Jesus, save me,' non-stop for three days." At its best, Byme's music aspires to this state of trance and transcendence, an aspiration reflected in the movie's big populist anthem, "People like Us," a beery plea for luv, redeemin' luv. Another song, "Radio Head," is about using one's brain as a transmitter-receiver. With its barbershop/beauty parlor characters expressing their hankering selves through pop songs, True Stories is intended to mutate between what Byme calls the "eye candy" of rock video and the more traditional turkey stuffing of conventional narrative film. The pageantry of Our Town seen at a slight planetary tilt, that is, with Byme himself in a black cowboy hat, serving as tour guide. (Howdy, pardner.)

In his movie, Byrne is a friendly ghost. Compared with David Lynch's Blue Velvet, which unscrews the lid of sleepy-town America to show us night crawlers in lurid feast, True Stories only dabbles in the bizarre. Sex, violence, and politics are subjects about which audiences already have mind-sets, Byme observes in his intro to the movie's screenplay edition. In True Stories Byme isn't probing for blood and semen. There aren't, he says, any "big, highly charged emotional interchanges." Instead, he deals "with stuff that's too dumb for people to have bothered to formulate opinions on." This affection and fascination with the banal everyday is at first very Warholian; it's the pictorialism of the passive. But unlike Warhol's, Byrne's big stare isn't blank, or even, on close inspection, passive. He isn't in the alienation biz.

No, if there's any artist Byme truly resembles in his pallor, his perfected otherness, his powdered aura, it's the writer-director-artist Jean Cocteau. David Byme has within him the romantic ardor about art to become—I hope it isn't the kiss of death to say so—the American Cocteau. Where Cocteau climbed smoke ladders of opium to choreograph new dances for the gods, Byme has his big stare peeled on the great empty horizon. (He shot True Stories in Texas partly because it afforded so much eyeball room in which to build his imaginary town. . .a big space for a big fabrication.) But, like Cocteau, Byme has diversified into different media and run the risk of appearing a pseud, a dilettante, a carnation in the buttonhole of the chic. And, like Cocteau, he can overdo the fey. "Mommy," a little girl once piped in a TV skit, "Daddy's acting pretentious!" Byme, sometimes, too.

But that comes with the territory. When an artist deals with the artificiality of passion and the passion of artificiality, the fragrance of strewn petals may scent the air. Such egotistical perfume can color perceptions. To paraphrase The New Yorker's Pauline Kael on Cocteau, these skinny guys are more resilient than they look. And Byme is one skinny noodle—he's elastic. So pretension doesn't seem to me as much of a peril to David Byme as too much aw-shucks sincerity. When Byme writes that people are the real wealth of the country or tells an interviewer, "I'm saying you can take what's in your backyard and give it respect," he's in danger of becoming a hip disciple of Frank Capra, patting the Common Man on his cowlick. Oh, I'm not arguing that Byme should stuff his characters with straw and leave them burning in the fields, just that he should resist the impulse to sentimentalize the lives of "little people." David Byme has found soul—he should spare us "heart." Soul is A1 Green and the great Aretha; heart is Frank Capra and Alan Alda. Soul beats heart every day of the week and twice on Sunday. As a Talking Head, Byme has been able to tap the passion of passion and give it testifying voice. Will he be able to do that in movies? "People like Us" certainly has testifying force, and he's already mapping out in his mind a second film that will have more story, less drift. David Byme may yet lead us down to the warm, funky, delivering waters. Let's trance.

If there's any artist Byrne truly resembles in his pallor, his perfected otherness, is powdered aura, it's the writer-director-artist Jean Cocteau.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now