Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE MYSTERY OF MADAME X

On the eve of the Whitney Museum's John Singer Sargent spectacular, GLORIA VANDERBILT unravels the story behind the social portrait that scandalized Paris

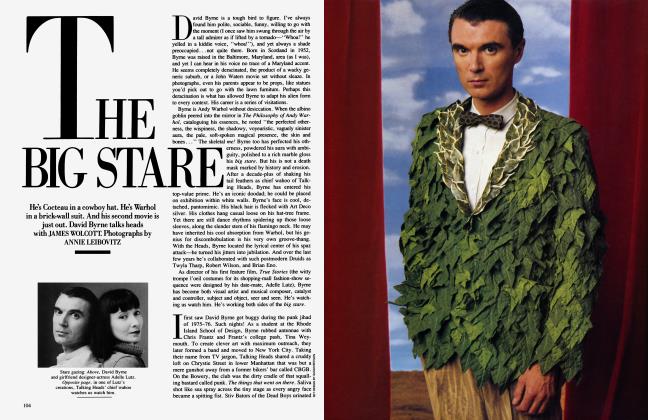

Madame X was twenty-four when the twenty-sevenyear-old John Singer Sargent painted her portrait. Of course, in the 1880s, women of that age looked older than they do now. Still, it is dismaying that something in her nature appears to be already set, jelled into a mold of discontent. There she stands by the table, her right hand pushing into its surface with a vulgarity of gesture, an aggressiveness throbbing up her arm, along the sinuous line of her shoulder, up to the neck, around her profile, and on down to the rather beefy hand holding the fan while grasping the satin of her dress. Even if Madame X does get what she wants and all her dreams come true, will she ever be satisfied? But then we see that sensitive nose, and in the quivering profile a different person comes to mind. Surely any mortal with that improbable nez retrousse can't be all that greedy. If only her mouth didn't curve down unmistakably. I hate to say it, but it is a bit mean, isn't it?

Who was the woman in Madame X, and why did the painting Sargent referred to as "the best thing" he'd ever done cause such a scandal at the Paris Salon of 1884?

History tells us that she was bom Virginie Avegno on January 29, 1859, in New Orleans. Her father, a lawyer of Italian descent, was mortally wounded in the Battle of Shiloh, and soon after, the widow—nee Marie Virginie de Temant and descended from French nobility—sailed for France with young Virginie. Once in Paris, the duo joined a colony of southern aristocrats who had distant relations in clannish French society—including the ever elusive, aristocratic circle known as "le noble faubourg."

In the world Mme. Avegno aspired to, presentation was all. From the moment she arrived in Paris, she plotted her daughter's brilliant future— that is, she spent time training her to find a "suitable" husband. From the start, Virginie was clearly a fascinator, full of potential, and Mme. Avegno devoted her considerable ingenuity to building her daughter's career as a "professional beauty"—a nineteenth-century term for a woman resourceful in presenting herself as the ultimate decoration at balls, openings of the opera, and so on. These beauties wore gorgeous dresses, and money—real or fantasized—hovered somewhere in the background. Whom they saw and what they did were noted in all the gossip and scandal sheets.

Mme. Avegno was determined to transform Virginie into a living work of art. (Indeed, Sargent's friend and biographer Evan Charteris noted that the art critic Louis de Fourcaud remarked that the figure in Madame X was "less a woman than as it were a canon of worldly beauty.") To accentuate the paradox of the rather coarse nose, which in profile turned into an antenna of delicacy, Virginie highlighted her hair with henna and wore it high on her forehead. Floury powders tinged with lavender were blended for face and body, and, as Stanley Olson suggests in his superb Sargent biography, Virginie may have ingested tiny doses of arsenic (a beauty secret in my grandmother's day that gave rise to the term "arsenic eaters") to coax along her already snow-white skin—to the point where it became hauntingly white. It appears that Virginie was not tall, but no matter—a professional in all her little ways, she carried herself with the authority of a master.

CHERCHEZ MADAME

Sargent gave aristocracy, a sense of grandeur, and respectability to whomever he painted. And the costume she wears is timeless, acceptable today.

BILL BLASS

It's all in the position of that finger on the table—the strength of its thrust—and the aggressive flare of the nostril. Her bone structure was superb. She had the audacity of the secure, the complete nouveau riche.

Of course, all portrait painters are victims of the nouveau riche. I've always thought she was a third-rate woman.

-DIANA VREELAND

Madame X? Provocative, alluring. A sense of humor under it all, rather like a Bea Lillie, with roller skates on under that dress.

MRS. DENNISTON L. SLATER

Jacqueline de Ribes comes to mind—the aquiline look. The portrait is a marvelous image of elegance, outrewithout being in any way a fashion plate. It is daring but not in the least vulgar. -JOHN RICHARDSON

Madame X is someone I've always wanted to know. If you saw her at the opera you'd follow her and sit at a table near her just to watch her. Of course, if you really did know her she probably wouldn't be mysterious at all. -DOMINICK DUNNE

Of course, it was Sargent's concept of her that is in the portrait. She was actually portly and chubby, a dumpling, not elegant at all. But she has a certain elegance sensationalized in the portrait. The nose was prominent, but thicker than Sargent painted.

AARON SHIKLER

In the decade before he set eyes on Virginie Avegno, Sargent also had been building a career. He was at the time greatly influenced by Robert de Montesquiou (a descendant of the old French aristocracy, dubbed "the Prince of Decadence" by his detractors) and the satellites around him, including Oscar Wilde. They espoused the philosophy of the Aesthetic Movement, which was popular in bohemian circles and held that art need not serve any moral or political purpose—art for art's sake.

It was during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when the Aesthetic Movement of Bohemia began to infiltrate the realm of the fashionable, aristocratic Faubourg, that Virginie Avegno appeared on the Parisian scene. Her comings and goings were widely reported, and rumors swirled around her marriage to the rich banker and shipowner Pierre Gautreau. (Tattle had it that Virginie had rejected her suitor at every turn—perhaps waiting for someone richer, or more Faubourg, to appear—but was finally won over by Gautreau's promise that if only she would marry him he would ensconce her in a separate wing of his house, for to breathe the very air she breathed was all he desired.) As Mme. Pierre Gautreau, Virginie quickly surrounded herself with the necessary accoutrements of a lady of fashion, giving little dinner parties and soirees, all in between the "personal appearances" at various balls and opening nights.

Given the aesthetic that Sargent and his circle admired, it is no surprise that once aware of Virginie he became obsessed with the desire to paint her portrait. He was drawn to the exotic, the mysterious, the curious. Before Virginie, other charismatic women had captured his imagination: the sirenic model for Gitana and the wildly romantic Rosina Ferrara—with her tangly pile of night-dark hair and erotic body—whom he had met on Capri several years earlier. It has been intimated by scholars that these were perhaps fleeting passions of fantasy, infatuations consummated only in the more enduring realm of his art. And when, in the early 1880s, Sargent became aware of another spellbinder—Mme. Gautreau— he fell for the facade she had so skillfully fashioned for herself.

What scandal her exotic appearance must have caused, given the era's classic, Edwardian concept of beauty. Everything about her must have offended: the fanfaronade entrances, the simplicity of her style (well ahead of its time), the lavenderpowdered body, the painted face, the Venetian-red hair. And in a time when jewels reflected the quality of the woman, how irritating it must have been to some that Virginie chose to wear none, convinced that they might compete with her natural sorcery.

(Continued on page 141)

(Continued from page 112)

From the moment Sargent became obsessed with the idea of painting her, Virginie—insatiable though she was for recognition—manipulated and eluded the painter very much in the way she had the unfortunate M. Gautreau. Sargent embarked on a courtship of sorts that began with a letter to Ben del Castillo, a mutual friend, enlisting his help to "propose this homage to her beauty" and urging del Castillo to stress that he was "a man of prodigious talent." Days and months passed before Sargent wrote to his childhood confidante, Vernon Lee, that he was about to start work on sketches for "the Portrait of a Great Beauty." He wrote: "She has the most beautiful lines, and if the lavender or chlorate of potash-lozenge colour be pretty in itself I should be more than pleased."

With verve Sargent began work on the portrait, but nothing went according to plan; it was rather like a honeymoon gone completely awry. After the first days of flushed splendor the bride seemed to lose interest, become preoccupied, and take on maddening habits. The weeks dawdled on as Sargent followed her from Paris to Les Chenes, her house in Parame, where he again wrote to Vernon Lee. "Still in this country house. . .struggling with the unpaintable beauty and hopeless laziness of Madame Gautreau." Desperate and hoping to recapture ardor, Sargent sketched her in various attitudes as she puttered her way through the day: leafing through the pages of a book, lolling on a love seat. Finally, Sargent and Virginie agreed she would stand next to the Empire table in the now famous pose.

When the painter left Parame for Paris with the unfinished portrait, the everhard-to-please Madame was, it seems, not at all satisfied. Yes, Sargent had captured her fabled profile, but there was the stagy comment of the shoulder strap resting suggestively on her upper arm (a detail that Sargent later revised), which no doubt gave pause even to the exhibitionistic Madame. And, more subtle and hard to define, there was the aura around her snakelike body as it stretched out alluringly from the black skin of her dress, an aura that suggested a woman who from birth had dedicated time, thought, and energy to the creation of her own image.

As we look at the painting today, it is hard to understand why it caused the public scandal it did. Why crowds gathered around exclaiming, "Detestable!" "Boring!" "Monstrous!" Why, through the corridors of the Salon, fierce discussions took place, women jeering "Ah, voila 'la belle,' " "Oh, quelle horreur!" while other voices countered with "Superbe de style," "Quel dess in." Charteris points out that the critics were outraged by the decolletage (the Figaro printed "one more struggle and the lady will be free"), the monochrome of the flesh tones, and the supposed flaws of drawing and shadow. And the Faubourg, which viewed Mme. Gautreau as a self-indulgent, turf-hunting femme fatale, must have been offended that a painter of Sargent's stature would not only choose to immortalize the "likes of her" but hang the result in the hallowed Salon of the Palais des ChampsElysees for all the world to see.

John Singer Sargent combined an artistic genius with the shrewdness of a businessman, planning his career much in the manner Virginie Gautreau planned hers. And, like Virginie, Sargent knew how to publicize. Perhaps the magnet of ambition had pulled them together, and their alliance had not happened by chance. But if, as some scholars believe, Sargent and Mme. Gautreau joined forces to show the fashionable French just what two American expatriates could do when they put their minds to it, the attention gained was not of the kind they had hoped for. In the melee that followed the opening day of the Salon, Virginie panicked and, along with her mother, demanded that Sargent remove the painting from the exhibition. All their tears, hysterics, and claims that the painting would ruin Virginie were to no avail. Sargent refused, and for Mme. Gautreau all was lost.

As for Sargent, his attempt to cultivate new Parisian clients resulted in the first adverse criticism he had ever received. Overnight, he was finished in Paris—the city he believed to be a paradise—and his golden light struggled in a hostile terrain. But not for long: Sargent soon moved to London to capture the English aristocracy in portraits that defined the style of an epoch.

And Madame X? Of course, we'll never know, but the scandal must have caused quite a tempest in that little teapot mind of hers. All for naught the striving to make her mark in a silly world of fashion that may have existed only in her head. How she had wanted to be a star! Instead, there she was, washed up at twenty-five, having to start from the beginning and invent herself all over again.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now