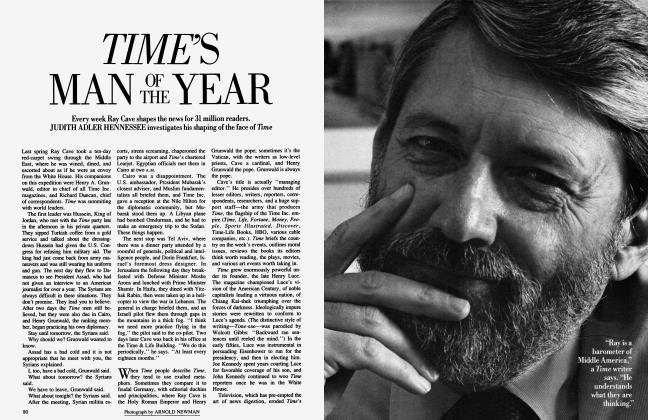

Sign In to Your Account

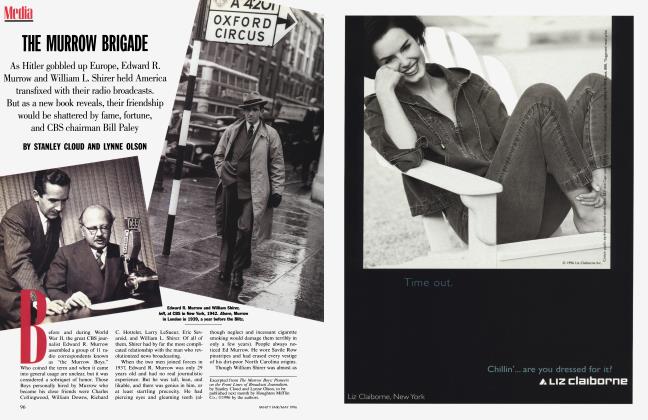

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Mother's Tale

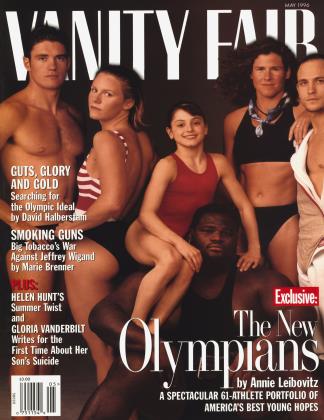

Born to wealth, she was also born to loss. But all the tragedy of her very public childhood could not prepare GLORIA VANDERBILT for the suicide of her 23-year-old son. In an excerpt from her poignant memoir, Vanderbilt remembers the day when the unthinkable happened

GLORIA VANDERBILT

Some of us are born with a sense of loss. It is not acquired as we grow. It is there from the beginning, and it pervades us throughout our lives. Loss can be interpreted as being born into a world that does not include a nurturing mother and father. It's as if we were trapped in an unbreakable glass bubble and forever seeking ways to break out and touch that which we are missing. I hope you don't live in this invisible glass bubble, but if you do I am one of you.

Those of us who are bom in the glass bubble are already prepared and never quite that surprised—each loss somehow echoes that first loss, the one we know so well. Something falls into place, so familiar it is almost a relief. Still, all my life, with each loss I have tried to break out of it. But instead of breaking out, I found myself breaking inward, each loss stripping me to a deeper layer of myself until I came to the final loss, the fatal loss that stripped me bare, the loss that had no echo, no memory of anything that had come before: the loss of my son Carter Cooper, a loss I thought I could not survive. But I did. The unbreakable glass didn't.

I wish my mother, Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt, were living in New York today, just around the comer, so that I could go round and have a cup of tea with her, talk to her as I never was able to when she was alive. She has been dead about 30 years, and when I think of her, which is often, my relationship with her keeps changing. I perceive her in ways I never had before, and as I do I come closer to her, and so, of course, to myself. The last time I spoke to her was on the phone hours after Carter was bom. She and her twin sister, my aunt Thelma, were to have come from California for the birth. Because I had two sons by a previous marriage, my husband, Wyatt Cooper, and I hoped for a girl, and my mother did, too. But as the time approached she became gravely ill and was unable to make the trip. I knew she was dying and for a desperate moment I was going to lie and say our wish had been granted. I wanted so much to please her, to make her happy to know that there would be a Gloria after she died, a Gloria after I died, a Gloria named after her, as I had been. But I didn't. I told her that she had a beautiful new grandson named Carter Vanderbilt Cooper. There was a pause, and then she said, "Why, Gloria, you're going to start a baseball team." I laughed with her, but what I really wanted to do was cry—cry for having disappointed her again, cry for not being able to break out of myself and tell her how I'd longed to be close to her.

Even in the years of my childhood when I'd been made to fear her, all I wanted was for her to love me, touch me, so that I could merge into her. And even now I wanted to tell her how sorry I was that I hadn't been born the boy she and my father, Reginald Vanderbilt, had wished for— he already had a daughter by a previous marriage. But he had taken it "rather well," she told me when I was 17, "when it turned out you were a girl." Yes, my mother was unattainable, always out of reach. But with the years I have come to understand it was not her fault—she was too young to have a child. But then, some women never should have one, and I suspect she was one of them. It never occurred to my 19-year-old mother or to my 44-year-old father that it was in any way singular, immediately after my February birth in New York, for them to take off for Europe, leaving Naney Morgan, my maternal grandmother, and Dodo, my Irish nurse, to take the newborn to Newport. My mother and father did not return until August, in time to supervise the annual fancy-dress ball given at my father's 240-acre estate, Sandy Point Farm. It is not surprising that these two women, maternal grandmother and devoted nurse, became the only real parents I came to know, love, adore, and feel safe with. Nor was it unpredictable when my father died unexpectedly a year later that my 20-year-old mother couldn't wait to shake free of Newport and move to Paris. Now I understand her eagerness. Newport was Newport—and, after all, it was 1925, and Paris was Paris, and it was all somewhere out there waiting to pursue: fun, life, that elusive it which will make our lives magical, brilliant, happyever-after. Of course, I didn't understand any of that until years later. Then, happy and safe though I was with my two devoted substitute parents, something was missing.

Excerpted from A Mother's Story, by Gloria Vanderbilt, to be published this month by Alfred A. Knopf; ©1996 by Gloria Vanderbilt.

Carter appeared in his pajamas, talking as if he were awake. But he wasrft.

There was an apparition that came and went. Sometimes it came up close, looking at me through the unbreakable glass, smiling before disappearing. And who was it? Mother, I was told. That's whose attention I kept trying so frantically to get. Later, after we moved to Europe, sometimes even desperately scribbling notes to my father—throwing them into the sea from one of the many ocean liners we seemed always to be on, or from car windows as we sped toward Monte Carlo or through the green of an English spring. (Had he loved my mother? Had he loved me? And if so, why didn't he come back?) But as these specks of crumpled paper wadded into balls crashed angrily through the glass bubble, they disappeared without a trace—for my father was dead.

Wyatt Cooper was born on a farm in Quitman, Mississippi, in 1927, graduated from high school in New Orleans, and attended the University of California at Berkeley and U.C.L.A., where he majored in theater arts. He became an actor on stage and television, a writer, and an editor.

We met at a small dinner in a friend's house in New York. From the first moment we looked at each other, before we even said hello, there was a shock of recognition between us. We knew we would be not only important to each other but also together and part of each other for a very long time. We were both in our mid-30s, and I had two sons by a previous marriage. Wyatt had never been married, and as we came to know each other, we both knew that we wanted the same things—a life together, a family.

"Why, Gloria, you're going to start a baseball team," my mother said.

The wide wedding band he designed was crafted by Buccellati. Inside, his words, engraved: Gloria—Wyatt—together without fear—trusting in God—in ourselves—in each other—with hope—faith—and love. When he gave it to me he said, "Lots of happiness ahead for you, little one." And what he said that day did for many years come true.

On December 7, 1977, Wyatt Cooper had the first of a series of massive heart attacks. He was in New York Hospital from then until he died on the operating table, January 5, 1978. He was 50. At the time, Carter was 12, Anderson, his brother, was 10, and they both attended the Dalton School.

Carter graduated from Princeton in 1987, while Anderson was completing his sophomore year at Yale. From college Carter went on to become a contributor to Commentary, and later an editor at American Heritage magazine. He was well on his way toward the future he looked forward to.

On July 22, 1988, in New York City, Carter Cooper took his own life. I was there when it happened, and I thank God it was me and not his father, who could not have survived. But I may be wrong about that—I thought I couldn't, either, and I did. It was an aberration—a terrible accident—a misadventure—a mystery-then, as it is now. Those of us who knew and loved Carter are still trvine to find answers.

To be pregnant has been for me each time the supreme joy. It is my greatest achievement, and it is hard for me to understand women who sometimes complain about the discomfort and loss of selfimage they experience when they are pregnant, because I never felt so centered, so beautiful, so loved, so important. I loved my body and my spirit as never before. Each day came as a miracle. There was not a moment when I didn't feel my best self. I was doing the greatest thing in the world without having to do anything— all I had to do was be.

Wyatt was sometimes asked if Carter and Anderson were aware of the part my family has played in American social history—as if there were some singular circumstance in being a Vanderbilt that required special handling in telling one's children about it—and he was reminded of Sarah Churchill's reply when asked what it was like to be the daughter of Sir Winston and Lady Churchill. "It was like having a father and a mother," she said.

The answer, of course, as Wyatt said, is that they did know, and it seemed no more novel or particular to them than it would if the name had been less well known, and no more tact or discretion was required in relating VanAprkm cfnripq than there was in talking about his own. less glamorous ancestors. Carter was fascinated by architecture and the preserving of landmarks; his principal interest in Vanderbilt history had to do with houses. He liked the Breakers at Newport better than Marble House or the house at Hyde Park; he wondered why Bergdorf Goodman, instead of tearing down my grandfather's Victorian mansion, which covered the block on Fifth Avenue between 57th and 58th Streets, couldn't have left it standing and simply set up shop in it and, in doing so, preserved it for posterity. He was curious about what sort of persons built the houses, particularly his favorite, Biltmore, in Asheville, North Carolina, and was fascinated by the fact that the estate had its own railroad and that the hundreds of acres of grounds were laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted, who designed Central Park. Both boys liked the idea that it was their great-greatgreat-grandfather William Henry Vanderbilt who brought to New York and had set up in Central Park the Egyptian obelisk called Cleopatra's Needle, around the base of which they often played.

One night late, midnight or so, when Carter was 11, his father was working, typing at his desk down the hall from Carter's room. Suddenly Carter appeared in his pajamas, standing there, talking as if he were awake. But he wasn't. Several times beVy fore, he had walked in his sleep, but this was the first time he was saying sentences that seemed to have no connection with this sudden visitation. As he spoke, Wyatt quickly typed his conversation, and when he stopped, he carried him back to his bed, sitting beside him until he was certain he was really asleep. The next day we showed Carter what he had said, but he had rta recollection of walking down the hall or of standing talking to his father or of being carried back to his bed, and was most amused by this sleepwalking/-talking event. I'm telling you about this because it connects somehow with what happened later. I don't know quite how, but I think it does, and you'll see why when I tell you about it. I'd give anything in the world to have that piece of paper with Carter's words on it. It's in a box somewhere along with my papers (I save everything). Or it could be in one of the many files of Wyatt's papers, which I have not yet gone through because I am unable to decide which university to donate them to. Or it may be I postpone, can't let them go, as I miss Wyatt so much. I am haunted by the thought that if this paper with Carter's sleepwalking words could be found they would give us clues.

It ties in with Carter's dread of taking naps in the middle of the day, because they always disoriented him. On that Friday afternoon of July 22 he'd fallen asleep on the sofa of our library—the heat was unbearable, but he hadn't wanted the air-conditioning on. I'd been with him, went out for a minute, and when I came back he was stretched out on the sofa, asleep. I went to wake him, but hesitated. He hadn't slept for several nights, he was exhausted—so I let him sleep. After his death I tormented myself, and still do. Had I not hesitated, had I awakened him, it might not have happened.

After Carter and Pearson, the girl he loved, had broken up, months before that July day, he had told me about it but didn't want to talk about it. At the time I tried as intuitively as I could to sense his feelings. She and I had become _JL .M._ friends, but since their breakup I hadn't heard from her. I respected his wishes and didn't want to intrude until he was ready to confide in me. Outwardly, he presented his usual self-confident, in control of his life. He liked his job at American Heritage, had many friends. Soon, I was hoping he would get involved elsewhere and that he wasn't grieving over the breakup. He didn't seem to be, but there was no way of really knowing. He kept it all very much to himself.

I kept telling myself he was at the age of breaking away, making his own life—still, I constantly asked myself whether I should intrude more aggressively into his life. Back and forth I went, trying to reassure myself that I had found the right balance, knowing that had I been Wyatt I wouldn't even be asking myself these questions, for they wouldn't exist. Then a few months later I went to New Orleans on business; when I returned, I told Carter that I'd sent Pearson a postcard, as she and I had often spoken of that city. He was furious. He walked out of the room, saying, "How about a little support here, Mom?" I followed him out into the hall, overcome with pain at my insensitivity, but the door to the elevator was already closing. When he'd said that, "How about a little support here, Mom?" it had never crossed my mind that I wasn't supporting him in every way possible. I kept going over and over what he'd said, trying to reach him on the phone, but it wasn't until days later that he returned my calls, and when he did he clearly didn't want to talk about her or what had happened between us.

I wished it had been me who had died instead of his father. Carter would not have shut him out. That communication they had, always had, would be there for him to connect with. I felt that then, and I feel it now.

From Pearson Marx, Wednesday, July 27, 1988:

What can I say to you? I can't stop thinking about you and Anderson. I can't stop thinking about Carter, and now I know it's true, that the things that happen in life can break a person in two. If it's like this for me, I can hardly bear to imagine what it must be like for you. Everything is haunted now. I keep looking around my room, lying on the bed where he lay beside me making me feel safe and strong. I keep going through the presents he gave me, the delicate antique boxes, the books, the jewelry. I keep going through those two years of my life, the two happiest years I've ever had, remembering all the things he gave me. A few weeks ago someone said to me about Carter: "He saw the beauty in you and committed to it." No one else has ever done this and it changed me. Carter showed me what it was to love and he loved what it was to be transformed by that emotion. It was as though I had been born again. And Carter did that for so many others. He saw the beauty when everyone else was blind, he could find it with his unerring eye, and once he had found it, he made it precious forever.

Gloria, I always used to say to Carter, "How did you get to be so good? How did you get to be as good as you are? You should write a book called How I Got to Be So Good." I used to say it playfully, though I knew the answer. That kind of goodness doesn't just happen. You and Wyatt and Anderson helped to make him the good, tender, beautiful creature he was. Before I even met you, I said to him, "Your mother must be a wonderful woman for you to have turned out the way you did," and he said, "She is a great lady." He loved you so much. He was so proud of you, so eager to say, Look, this incredible person is my mother. He worried about you too—he was such a worrier, as we know. He used to say, "I want her to be happy, how can I help her to be happy and strong?"

"I m moving back home, Mom'' he said, back into his old room on the top floor.

So when I wonder what I can say to you, I can say he loved you more than anything. I can say that I will love you and be grateful to you forever for giving him life, for bringing him into this world. I can say that he will be there beside us like an angel when we are sad and suffering, but that in a way he will be even closer to us when we are happy and laughing. Carter's expressive face was made for happiness. He had the greatest laugh: full-bodied, strong, rich with the joy of living. I know he is with us, urging us toward the time when we will be able to laugh again so that he can laugh with us.

he morning of July 22, Carter arrived unexpectedly. He now had his own apartment several blocks from his office. It was Friday around 11 A.M. and the hottest day of the year. "I'm moving back home, Mom," he said, back into his old room on the top floor, where he had lived during his days at Dalton and until he went to Princeton. How great, I said, but why not take Anderson's room, as he was in Washington that summer and later would be at Yale for his senior year. The two rooms were next to each other, and when we moved in, the boys had had much argument about which should have the larger room. Anderson finally had won. The room had a fireplace and spacious terraces around the top of the building. Carter was pleased about having Anderson's room, and he went over to the door leading from my bedroom to the terrace. The door was closed, and he looked out longingly across the river. "I can't wait to go to Southampton," he said. Our family house had been rented for the summer, and I said we'd go there the day after Labor Day, as soon as the tenants were out.

Then he came over and sat beside me on the foot of the bed. He put his arms around me and said, "Oh, Mom, I love you so much." I love you, too, I said, and we both laughed because I had rollers in my hair and they'd gotten squashed against his head as he hugged me. Can you stay for lunch, I asked him, or do you have to go back to the office? "No, I'll be here." I'll make spaghetti, I said, and we'll have lunch together and talk. I had a meeting at 12 at home which would take only half an hour, and I looked forward to lunch and the afternoon with him, eager to know what had brought him to the decision to move back home.

While I got myself together for the meeting, he went into the kitchen, where Nora, my assistant, who had known Carter since birth, was fixing lunch. Just as he did, Anderson called from Washington and I told him the good news and he said it was fine with him for Carter to take his room. I was almost ready when Nora came in to tell me the people had arrived for the meeting. I told her with joy that Carter was going to be moving back home. "Is he all right?" she said. "What do you mean, 'all right'?" I was almost annoyed with her. What could not be "all right" about his wanting to move back home? But I didn't pursue the matter. The people were waiting, and I was eager to get the meeting over with so I could get back to Carter.

The meeting over, I found Carter upstairs lying on Anderson's bed. There were two sliding glass doors covering the wall which looked out over the terraces and the East River, and in front of the river a walkway leading into the park. He had opened the glass doors and the heat in the room was overpowering. Don't you want me to turn on the air-conditioning? I said, sitting down beside him. "No," he said, "it's fine the way it is." How about some lunch? I asked him. "That would be nice," he said. I told him I'd go down and arrange to have trays in the library. Years ago I'd discovered a recipe for spaghetti sauce that I'd make batches of and freeze, and this had become Carter's favorite meal. Soon it was ready and I went upstairs to him. He was lying on the bed as I'd left him, looking out through the doors toward the river. We went downstairs to the library and as we had lunch he told me he hadn't slept for several nights, and then he asked for more spaghetti. After you finish it, I said, why don't you stretch out on the sofa and let me turn the air-conditioning on? "No, leave it as it is," he said, and after a while he stretched out on the sofa, asking me to cover him with a quilt and for a pitcher of water, he was so thirsty.

Directly behind the sofa was a large window with a view of the river. He drew the quilt around him and stared out. I sat beside him. He looked at me and said, "Mom, am I blinking?" I was surprised, reassuring him that while he was asking me he had blinked several times. Carter, are you taking anything? "No," he said. Carter had never done drugs, although many of his peers had, and we had often discussed this. He was very health-conscious, worked out at the gym, abhorred smoking, never drank anything more than an occasional glass of wine at a party. Drugs had no place in his past, present, or future—and, indeed, the autopsy performed after his death showed there were no drugs in his system. Once, after having a tooth pulled, requiring anesthesia, he told me how he hated the anesthetic because it had made him unconscious. He didn't want to miss a moment, a second, of life.

It never occurred to me that day to ask him if he was taking any doctor-prescribed medication. He'd had allergies and asthma since he was a child, and I knew he had chosen to go to a new doctor recommended by a friend, but he had been reticent about it and I hadn't pressed. He seemed to be in charge of his life, and again I thought it part of growing up, of wanting to make his own decisions. Later, I discovered what the doctor had prescribed—a new respiratory inhaler. Soon after Carter's death I spent many hours with J. John Mann, M.D.—in 1988 at Payne Whitney in New York, later at the University of Pittsburgh's Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic in Pittsburgh, and in 1995 at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center in New York—talking to him, going over each moment, each detail leading up to Carter's death, trying to find answers to what had happened. Over and over, he kept coming back to the respiratory inhaler. Perhaps it would explain why Carter had requested the quilt and pulled it around him even though the day was so hot, why he was so hungry, so thirsty—would explain why Carter thought he wasn't blinking, why his eyes were glazed when later he came into the room before he ran up the stairs. This respiratory drug is described in the Physicians' Desk Reference as potentially causing central-nervous-system stimulation. An article in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (1988, Volume 81, Number 2, pages 351-60) attributed "agitation, insomnia, terrifying nightmares and acute paradoxic, depressive states" to medications for asthma such as theophylline. Was his asthma worse and requiring the use of more medication? This drug was potentially both friend and foe.

Was the asthma a threat to his mind? To quote once again from The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology:

Classic descriptions of the mental effects of hypoxia are to be found in the works of Haldane et al. and have since been amply confirmed. Marginal acute hypoxia produces subtle degrees of impairment of consciousness with poor judgment, diminished alertness, reduced attention span, difficulty in performing intellectual tasks, in judging time, and with memory, particularly in the area of new learning. Emotional symptoms can include emotional lability, irritability, or depression. Anxiety may be a notable feature of increasing hypoxia. There may be more obvious mental slowing, irrational fixed ideas, and uncontrollable outbursts. Without reason [the patient] may begin to laugh, sing, burst into tears, or become dangerously violent.

The article concludes:

The several mechanisms by which allergic diseases can lead to psychologic changes have generally been poorly acknowledged. We need to be more aware of the frequency of higher mental function impairment in moderate to severe asthma and of the nervous system side effects of many of the drugs that we prescribe. It appears very likely that misinterpretation of the significance of observations of such changes can be the origin of erroneous conclusions.

It is my belief that the respiratory inhaler was the key to the demon that took Carter's life. That July 22, when I asked him if he "was taking anything," he knew I didn't mean any doctor-prescribed medication, which we both would have trusted, so when he said no, I knew that he wasn't taking any so-called recreational drugs. Yes, he was relieved when I told him he had blinked, and we laughed about it. But I was puzzled. Would you like to call Dr. Young? I said. This was a cognitive therapist recommended by another friend, whom I had only recently heard Carter had started seeing. Later I found out that he had canceled an appointment earlier that week with Dr. Young, telling him he no longer needed to see him. No, he had no interest in calling Dr. Young.

How about my reading to you? I said. We often did this together and it was one of my greatest pleasures. "That would be nice," he said, and after some discussion we settled on a short story in The New Yorker by Michael Cunningham—"White Angel." In the story, while his parents are having a party a young man runs and crashes through a closed plate-glass door that faces a garden and he is killed. That's terrible, I said when I finished reading. "It's a good story," Carter said, and it was. We discussed it for a while and then I asked him if he'd like me to read anything else. "No—I'll rest a bit." How about my getting a movie we can watch tonight? "Road Warrior, " he said. We've seen that so many times—how about Bertolucci's 1900, just out on video. "Yes, I've been wanting to see that," he said, and I went into my room to get the number of the video rental to call. Then I went back into the library and asked him again if he wanted me to turn on the air-conditioning. But he didn't, and I left him to rest, going into the other room, leaving the door open. It was unbearable, the heat. I'll be close by, I said—let me know if you need anything, I'm right here.

Carter come back I shouted, and I thought he was going to. But he didn't— he let go.

If Carter had intended to take his own life, he never would have done it in our home, in front of me.

From time to time that Friday I went back and forth to see if Carter was all right. Every time I passed the open door going into the library he was there, still asleep, stretched out on the sofa. I was grateful that he was getting sleep at last after those white nights. At about seven I was in my room taking off a pair of earrings when suddenly the door opened and Carter came in. Dazed, he came toward me, saying over and over, "What's going on? What's going on?" There was nothing going on—the room was quiet, we were alone, there was no radio, there was no sound. Nothing's going on, Carter, no one's here except us, I'm here, Nora's here, we're all here, nothing's going on, the Bertolucci video's here, nothing's going on. I was standing close to him, speaking very softly. He was in a daze, and I kept talking, talking, softly, softly, trying to center him, bring him back to himself. He clearly didn't know me, or where he was, or who he was—disoriented like someone woken unexpectedly from a deep sleep, his eyes glazed. "No, no," he said, shaking his head, pulling away.

I tried to hold him, but he had suddenly become determined—running like an athlete, fast, really fast, with purpose, energy, as if he knew where he was going, knew the destination. I ran after him, trying to pull him into the library—Carter, come here, I have to talk to you! I was panicked, almost screaming, trying to hold him, but he was running so fast, and although I had sneakers on he got way ahead of me as he raced through the halls, on up the stairs. When I got there, Anderson's room was empty. The glass doors were open exactly as they had been left that morning. There was a low stone wall surrounding the terrace, and Carter was sitting on top of it, about 12 feet away from where I stood, his right foot placed on top of the wall, the other on the terrace floor. What are you doing, Carter? I shouted, starting toward him. He put his right arm out, straight out rigidly in front of him; there was something military about it, extremely forceful, the palm of his hand held firmly out to warn me off. No, no, he said, don't come near.

Don't do this to me, don't do this to Anderson, don't do this to Daddy, I was screaming, reaching out, straining toward him. Will I ever feel again? he said, and I screamed Yes, you will, I know what pain is and I can help you, Dr. Young can help you, and I started down on my knees, my hands begging out to him, and I was going to say, I'm your mother, but I didn't, because he shouted No no no to me, don't do that—and I quickly obeyed— got off my knees—stood there reaching out to him. Do you want me to get Dr. Young on the phone? I shouted. Do you know his number? he said. No, I said, and he got up fforn the wall, standing straight, staring past me, past the river, the distant bridge, staring ahead as if he didn't see them. He stood with a terrible rigid tenseness and strain, struggling, battling inside himself. Then he said the number loudly and very clearly—then he shouted out Fuck you and I started toward him, but he had sat back again in the same position on the wall, only this time he was looking down at the walkway 14 stories below, mesmerized, swaying back and forth. I stood there afraid to move, afraid it would send him downshouting Carter, Carter.

Then suddenly a helicopter passed above us, high up in the fading summer light—he looked directly up as if it were a signal, then turned and reached his hand out yearningly to me, and I moved toward him, my hand reaching for his, but as I did he moved, as deftly as an athlete, over the wall, holding on to the edge as if it were a practice bar in a gym. He firmly and confidently held on to the wall, hanging down over the 14-story building—suspended there. Carter, come back, I shouted, and for a moment I thought he was going to. But he didn't—he let go.

T ran down the stairs to the kitchen. "It X couldn't be," Nora said. Yes, yes, I kept saying. But she wouldn't believe me and said, "Come, let's go and find him."

Together we ran up and I stood while she went looking over the wall, but she saw nothing and started running around the vast terraces looking for him. She was right, of course, it hadn't happened. But when she came back Carter wasn't with her. "I'll go down to the street," she said, and I went on down with her into my room and stood in the spot where Carter and I had stood minutes ago. Something was in my hand—one of the earrings I'd been taking off when he'd first come into the room; apparently, I'd held on to it, but was only now aware of this. It had been in my hand as I ran after him up the stairs, onto the terrace, as I'd stood there shouting to him, reaching out to him— holding on to it as if it were a magnet that would pull him off the wall, back to me.

Nora came back upstairs and said . . . police. Yes, yes, I urged, we must call them, do that, they are the authorities— they would be the ones to tell us it hadn't happened. I too started calling—Dr. Young, certain that he too, an even higher authority than the police, would tell me it hadn't happened. But all I got was his voice coming from an answering machine, with no referral number to call, so I left a message. I had never met him, and later, when I did, he told me that when he picked up his messages Carter's name was cut off and he had sat up all night going through the names of his patients—dismissing Carter immediately as being the last person to consider. When he finally heard, he still couldn't believe it. I kept going through my address book, calling people, friends I loved, at random—certain that the next one was going to be the one telling me it had not happened. One man, a lifelong friend, just said, "Did he leave a note?" It was like a line of dialogue from a detective in an old movie—and the insensitivity of it may be fascinating to me now, but at the time it took my breath away.

Thursday, the night before Carter died, he'd made a call around midnight to Pearson, the girl he loved, the girl he'd broken up with. He wanted to see her— right away. It was late, it was raining, she needed to wash her hair, she wanted to look pretty for him, so they talked for a while—and then made a date to see each other for dinner on Monday, July 25. She called my house on Friday at eight o'clock—she couldn't stop thinking about him and had been trying to reach him all day at the office, but he wasn't there and his number at home didn't answer. Nora, who answered our phone, told her what had happened. Stunned, she said, "Is he all right?"

Suddenly there were sirens, and the room was full of people. Dr. Tuchman, our family physician, was standing in front of me. He would be the final one to know. I looked close into his face, saw it so clearly as I said, Tell me it's not true? I looked in his eyes and knew then that it was true, and I sat down on a bench in the hall and my mouth opened and a sound came—people were all around me, paramedics, one taking blood pressure, police were there, and the sirens, but the sound filling the rooms, the sky above, was not sirens—it came from an animal—on and on it went—but the sound was coming from me, and as it came—on and on—I split in two and the glass bubble cracked into a million pieces and was no more.

I kept going over it, moment by moment, from the time Carter came into the room to the time it happened. I still go over it, now and every day of my life, agonizing over what I could have done to prevent it. Pretended to faint—he might have come out of himself to help me. How stupid to have asked him for Dr. Young's number—I should have had the wit to tell him Dr. Young was already on the phone, come in to speak to him. I could have told him a car was downstairs—right now—waiting to take us to Southampton, where that morning when he first came into my room he had so longingly wanted to go. And I kept thinking how when I'd first seen him sitting there my impulse was to risk the distance, rush across the terrace, and, with all my strength, try to pull him off the wall, but I'd discarded it instantly, as seeing me running toward him might have sent him over before I got to him. But maybe I should have done that. Then—had I been calm and spoken softly as I had before, before he started racing out the door, racing upstairs, spoken in the softly lulling sound I had used when he had first come into the room dazed, instead of shouting to him when I saw him sitting on the wall—Carter, what are you doing? Had I done that—I could have saved him . . . But it happened so fast, my brain cutting in and out as if I were on a careering roller coaster, trying to stop it.

I knew that if Carter had intended to take his own life he never would have done it in our home, in front of me. Something had clicked him into something else, and the only thing that stopped me from clicking into it with him and following him over the wall was Anderson.

My bed had become a raft where I lay far out to sea, and one by one, or in threes or fours, there would come a life support, a friend, climbing onto the raft to be with me. I stayed there sobbing and sobbing for days, without eating, without combing my hair or brushing my teeth, without changing my nightgown or showering, until the day of the wake—and they understood. I didn't sleep but took no sedatives or medication. I didn't want to—what I wanted was to talk and talk, go over it again and again, and it kept me alive in some strange way I still don't understand.

The losses in my life over the years had been many, each loss stripping me down to another layer, bringing me closer to the center of myself. But the loss of Carter had not stripped off another layer—it had exploded the core of what I had known myself to be, and a new self would have to be born if I were to survive.

I started writing letters to Carter:

Monday—Afternoon— Carter—I don't know how to start this letter. It's a letter to you but it's really a letter to myself. I believe there is a logic in the world that comes from a Great Intelligence and that we have our place on earth and have been born and placed here and there is a logic and reason behind it. Carter, I'll never be the same. The pain I knew as a child I always thought of as my test and I imagined that nothing could ever hurt me in that way again. There was always a center hard as a diamond that no one could reach or take away from me. It was my final secret. ... I am at the end of my life now, and all I want is to see that Anderson is all right, and Nora, and when that is done I want to go to you and Daddy. For I am certain that there is a place where you wait for me, a place far beyond my flawed and frail perception. And so there is no goodbye for us. Things will happen as they are meant to happen. With the same logic that took you from me.

Dazed, Carter came toward me, saying over and over/What's gomg on ? What's going on"

Thursday—Carter—another day has gone by. I miss you. Sometimes I feel you are close by. Then there are times you are lost to me but inside the pain is there and I know it will never go away. Carter, I didn't understand what happened to me as a child and I don't understand what's happening now. I don't understand anything anymore. All I understand is pain.

Saturday—Carter, I believe beyond what has happened that there is a force, a Great Intelligence that is God—that nothing could have stopped you leaving as you did. That you know why now, that you are with Daddy— that you both know why, and someday Andy and I will know and understand the logic of what happened.

Saturday—Carter—I don't have to pretend anymore about anything. Carter—I know you loved me and you knew I loved you. Destiny.

Friday—Carter—sometimes you are here so close—today, not present in that way. Are you all right? Are you with Daddy? Are you close to me as you are close together? Is it going to be all right—or am I going through the door to you?

As strangers we entered the room of the support group I joined, but later, sitting in a circle, we were not strangers, not even friends, we were a family, one that does not judge, for pain had stripped us bare. Oh yes ... we knew each other well.

After our meetings I would walk home

and find myself in a park stopping beneath a tree to circle the trunk with my arms, to feel my spirit merge on up to the branches, on up to the sky above. I felt wordless communication with strangers passing; others sitting at outdoor cafes, a woman walking her dog, were not alien to me, nor was I to them. I knew their pain, their joy—yes, even joy—for although I resided in a dimension where even the memory of it seemed forever lost to me, I knew joy existed somewhere for others. I too had once had it in my life. No one would ever be a stranger to me again, for I knew that if they had not already, the day would come when they would have to live through tragedy and loss as we all do and this connected us, not only now but forever. By giving myself to the visceral pain that possessed and consumed me, and by not fighting it, as each moment passed I gained energy, more than I'd had the moment before, and with this came an overpowering will to survive, because if I could it might help others who had experienced tragedy, for anyone who meets such testings of the soul without escaping into a glass bubble is helping to quicken the vibrations of the whole earth.

Sunday (Juniper room, Galisteo Inn, Galisteo, New Mexico)— Carter—there is great peace, quiet here. At my first session at the Light Institute with a facilitator, Karen, I talked about you, about how it happened, how I don't understand but believe that it's part of the plan, the designnothing could have been done to prevent it. . . . I lay with eyes open for a time. Karen, standing behind my head, held it in her hands and after a time touched my neck and ears as I breathed deeply. My eyes closed and I entered a hypnotic state. The session was to concentrate on the emotional center and the higher center.

I envisioned a white light going through the top of my head, going on down into my chest, the touch of her hands sending it there into my stomach, which became sore, and a hard ball of glutinous texture was felt to be there. I envisioned it to be an embryo, an embryo who was me, who felt unworthy to be born, who wanted more than anything else to be loved, who was afraid. Then the embryo became warm and decided to be born. It rose up to Karen's hands. A golden light suffused me as it moved up into my head—higher— and I imagined becoming an ancient tree rooted in earth with tall branches reaching to the sky like the tree outside the window at the inn. But these branches had leaves and flowers and a nest and within the nest an egg that held a bird that broke free and flew away, and as it did, the tree cracked asunder and I was free.

The embryo gave me a gift of golden light so that I would not be afraid.

Carter, are you close by? Are we separated only by a veil?

A suicide is defined by the Random House Dictionary as "a person who intentionally takes his or her own life." Often, later, when Carter's friends from Princeton and I talked, they said that whenever discussions had come up about suicide Carter always said it was something that he himself could never do. What happened was an aberration, like a stroke, or lightning hitting. It may have been triggered by his allergy doctor's prescription.

But I still don't know, none of us do, the reason why it happened or what demons took possession of his fantasies as he slept so deeply on the sofa in the library that staggeringly hot July day. I believe someday we will, and it will fit into place like the last piece of a puzzle, and when it does we will understand that there is a reason why terrible things happen in the world—we will understand the tragedies that come to us—understand why, in the same way that we understand joy but do not question it. The day will come—maybe sooner than we think— when it will be made clear and, simplistic though it sounds, I believe the answer itself will be so simple, so right, so true, that when we do understand we shall no longer cry out Why, God, why?— for with understanding we shall be out of pain, out of darkness into light. It takes a great leap of faith to believe this, but I do, and in some measure it has brought me peace.

Each day, each year that passes as I live with Carter's death, I come to see it in perspective to the tragedies that have happened and are happening every day in our world—the Holocaust, Rwanda, Bosnia—tragedies so indescribable that one mother's pain is maybe not so important after all. Except to me, of course. But perhaps in some small way it will be to you—perhaps if you are suffering from loss and feel you can't go on, it will reach you, for what I am trying to say to you is: Don't give up, don't ever give up, because without pain there cannot be joy, and both are what make us know we are alive. You have the courage to let the pain you feel possess you, the courage not to deny it, and if you do this the day will come when you wake and know that you are working through it, and because you are, there is a hope, small though it may be, a hope you can trust, and the more you allow yourself to trust it, the more it will tell you that—although nothing will ever be the same, and the suffering you are working through will be with you always—you will come through, and when you do you'll know who you really are, and someday there will be moments when you will be able to love again, and laugh again, and live again. I hope this will come true for you as it has for me.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now