Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

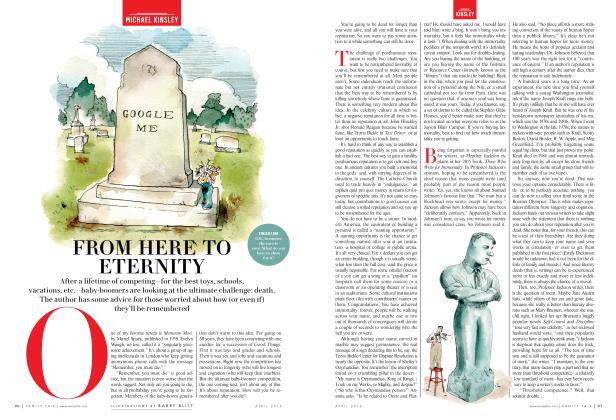

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFlamboyant retailing heir Gene Pressman's plan to create an achingly chic empire that would stretch from Madison Avenue to Wilshire Boulevard has wreaked havoc on the family business—and on the family as well

May 1996 Jennet ConantFlamboyant retailing heir Gene Pressman's plan to create an achingly chic empire that would stretch from Madison Avenue to Wilshire Boulevard has wreaked havoc on the family business—and on the family as well

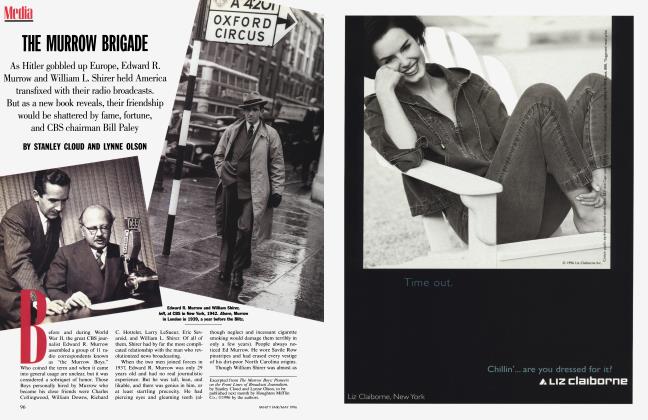

May 1996 Jennet ConantIt took just one look. If anyone doubted that Barneys, New York's chic shopping emporium, was in trouble, the worst appeared to be true when Gene Pressman walked into Judge James Garrity's bankruptcy court on a cold January afternoon. He was wearing a dark-blue suit, his hair was short, and he looked surprisingly pale.

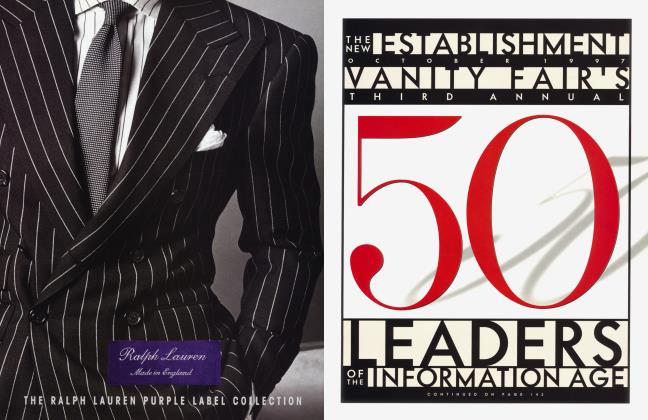

It was the suit that gave him away. Fashion designers, merchants, and manufacturers—the cognoscenti from New York and Paris to Milan—went numb, though not mute. Gene Pressman, the flamboyant retailing heir with the rock 'n' roll hair and cocky manner; Gene Pressman, whose daily uniform was a houndstooth Hermes jacket, jeans, white button-down shirt (monogrammed on the inside collar), white socks, and penny loafers. This was a man too cool for anything as pedestrian as pinstripes.

No single image could have telegraphed more about the desperate state of Barneys' finances: at the time of the actual Chapter 11 filing, the company's cash totaled less than $1 million, a perilously low amount for a national operation with 2,000 employees. But the chatter over Gene's banker's suit seemed sadly ironic. His father, Fred, had spent most of his days selling "sleeves." As had his grandfather, the original Barney, who in 1923 pawned his wife's engagement ring for $500 to open a tiny discount men's shop on Manhattan's lower West Side. Suits were where it all began for the Pressmans.

Now no one is sure where it will end.

Bob's wife, Holly Pressman, called her in-laws "the most dysfunctional family I've ever seen."

Gene Pressman, 45, shares the title of Barneys C.E.O. with his stodgy brother, Bob, 41, who oversees the company's finances. Yet few would dispute the matter of who has guided the privately held empire in recent years. It was Gene who removed the apostrophe from the store's logo and transformed Barneys on out-of-the-way 17th Street into a destination, a high-style store which promises—as Bloomingdale's and Tiffany's once did—all the glamour and sophistication of the Manhattan dream. It was Gene who masterminded the creation and construction of Barneys' impeccably turned-out new branches (on Madison Avenue, in Chicago, and in Beverly Hills), where details such as lacquered walls, gold-leaf ceilings, and floors of Italian-marble mosaic helped boost total costs to nearly half a billion dollars. It was all Gene. Some would say. The success and the excess.

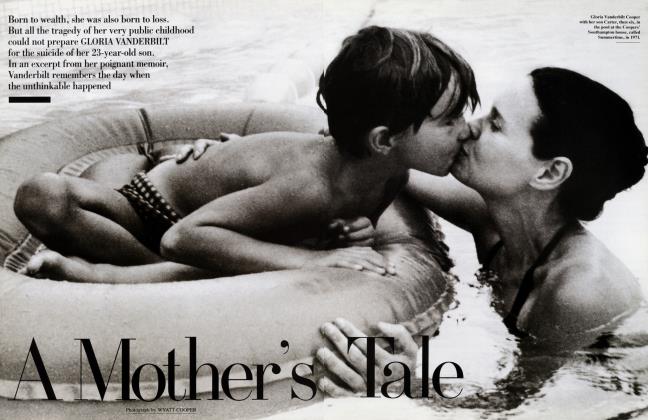

And now Barneys hangs in the balance—or, more specifically, control of the three new stores, the old flagship place on 17th Street, and the 16 branches across the country. At first, it all seemed like one of those near-biblical reversals of fortune, in which another flashy upstart of the 1980s is humbled. Yet as the Barneys saga unfolds, more complex dimensions are revealed. The brothers Pressman, it seems, are pitted against each other in a devastating family drama made more intriguing by the clan's long-standing genius for keeping up appearances. For years the Pressmans have been burdened by rivalries so intense that there are those who see the brothers' mutual loathing as the bonfire burning beneath the company's current financial predicament. A family friend confides the story of Bob's wife, Holly, calling her in-laws "the most dysfunctional family I've ever seen" after an argument several years ago that left Gene and Bob barely speaking.

And that's only Act One.

Barneys' bankruptcy filing has cleared the runway for the even messier battle between the Pressmans and Isetan, the Japanese retailing giant which has been their partner for seven years. Between 1989 and 1995, Isetan handed over $616 million to Barneys, quietly footing almost the entire bill for the expansion of the business into a chain of some of the most sumptuous stores on the face of the earth. But after allowing the Pressmans to publicly represent the partnership in a number of self-serving ways, after seeing spending accelerate endlessly, after being given what it claims was misleading financial information, Isetan rebelled. "We believed our partners," said the company's vice president, Michio Johmori. "Thinking back on it now, we did make a mistake."

After filing for Chapter 11, the Pressmans fired the first shot by suing Isetan, contending that the company's new management had reneged on a commitment to convert its "investment" into equity in Barneys. (Isetan says that Bob Pressman once proclaimed that the Japanese would get equity "over my dead body.") The Pressmans insist that sales are healthy, and they feel that Isetan, previously interested in long-term profits, has pulled the rug out just as the new stores have gotten going. The Pressmans say that the lawsuit is simply a way to retrieve $50 million previously paid to Isetan. In fact, Barneys' version is so at odds with Isetan's that the two sides are not even in agreement over the basic points of their unusual contract, which now appears to have been fundamentally vague. They do not even concur as to the ownership of the valuable Madison Avenue, Beverly Hills, and Chicago properties.

Outraged by what it views as the Pressmans' legal maneuvering, arrogance, and lack of remorse, Isetan is out for blood. They do not see how they can continue working side by side with the brothers. In a January legal action, Isetan demanded that the Pressmans pay back $167 million in loans that the brothers personally guaranteed—based on networth statements that estimated their wealth at $50 million each. But a source close to the Pressmans says that the personal guarantees are worthless because all of the brothers' assets—from their company stock to their fine homes—are tied up in family trusts administered by their father. A source close to Isetan suggests that the company is angry enough to try to place a lien on the family trusts, a move that would prevent either brother from being able to draw a dollar.

And closely eyeing Barneys' dollars are dozens of irate designers and vendors who were left holding the bag on merchandise shipped last spring. Topping this list is Hugo Boss, which is owed $2.4 million, followed by Donna Karan, which is owed $2.1 million, Marzotto, which is owed $1.1 million, and Hickey-Freeman, which is out $1 million. In addition, Barneys is more than $300 million in debt to banks and insurance companies, costing the company about $27 million in interest annually. Topping that list is Chemical Bank, owed in excess of $71 million.

Lacquered walls and floors of Italian-marble mosaic helped boost total costs of the three showcase Barneys stores.

In an industry that feeds on rumor, the Pressmans have been innuendoed to death since the opening of the Madison Avenue store in 1993. The brothers, word had it, couldn't pay their bills. Designer Todd Oldham stopped selling to the store years ago, he says, because of its "credit problems." Most designers, however, continued to do business with Barneys for the simple reason that they felt they couldn't afford not to.

The Medicis of men's wear for years, the Pressmans are renowned for bullying suppliers. When Barneys was trying to force top labels into selling to their new store over the objections of the uptown competition, they became embroiled in nasty feuds with Armani (they won) and Ralph Lauren (they lost). Barneys has also, on occasion, blackballed suppliers who talk to the press. After men's-wear designer John Bartlett complained that Barneys had fallen behind in payments, his business suffered. Even now, few designers will speak on the record for fear of antagonizing the Pressmans. The brothers' heavy-handed tactics, however, account for the force with which they are now being attacked in some quarters.

In showrooms and over lunch at the Royalton, the overwhelming conclusion of Gene Pressman's fashion peers is that his ego has been his undoing. "It's always been all about his arrogance," snaps a well-known designer who is owed money by Barneys. "They had a 'Let them eat cake' attitude," says a fashion director who believes that Bob Pressman is every bit as egotistical as Gene.

"It just goes to prove the old adage," observes a leading Seventh Avenue Figure, "that the third generation always runs the empire into the ground."

A charter member of the "lucky-sperm club," as one of his golfing buddies puts it, Gene Pressman was born rich, good-looking, and charming—especially to women. Of Phyllis and Fred Pressman's four children, Gene—the first boy—is his doting parents' favorite. Though he grew up in the genteel New York suburb of Harrison, he comes across like a scrappy street kid. Dauntingly fit, he has a lean, muscular build from years of boxing. When he is angry, his voice takes on a tough edge and can sometimes seem slightly dangerous, with his revved-up energy threatening to explode.

A handful from the start, Gene bounced in and out of boarding schools before graduating from the Hackley School, in suburban Tarrytown. As a teenager, he announced he wanted to be a "rock star" and enrolled under duress at Syracuse University, where his fellow students included Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell, who would found Studio 54, and publicist-to-be Peggy Siegal. A classmate recalls Gene as not lacking in confidence: "He used to kid around [about the store] and say he was looking forward to the day his grandfather was no longer around, so he could call it Geno's."

After graduating with a degree in radio and television, Gene headed for L.A. and the movies. He lasted two months as a gofer on the movie Black Gunn. "What can I tell you?" he said later. "I'm an impatient guy."

So he returned to the family store. In 1976, exhibiting a keen eye for models and miniskirts, young Gene broke the Barneys tradition of selling only men's clothes by opening a small women's boutique. Before long, he had filled the top two floors of the store with the sexy little dresses of Armani, Chloe, and Missoni. He even started his own youthful fashion line, Basco. Gene loved attending the designer shows in Europe, showing up at formal parties in tight jeans, T-shirt, and tan. He created a stir with his club-hopping lifestyle and girl-in-every-showroom exploits, and he was known for his appetites—for sex and cocaine. "In my younger days, before I was married," he admits, "I lived a more free-spirited life." Some legends never die: Almost everyone interviewed for this piece had an unprintable Gene Pressman story. Many involved beautiful blondes, unusual places, and outrageous public displays of affection. As Vogue editor Anna Wintour once noted, "Gene is one of the few straight guys in the business, and he enjoys it."

By the late 70s, Gene was pushing his father to let him add a full women's store to Barneys. But Fred Pressman, who had transformed his father's tiny place into a shopping mecca featuring Giorgio Armani and the most exclusive international men's-wear brands, including Brioni and Piattelli, understood that women's wear was risky. Yet he also understood that his son deserved the freedom his own father had given him. At Phyllis's urging, Fred reluctantly relented.

Gene threw himself into every detail, hiring a phalanx of famous architects and designers: Peter Marino in New York, Andree Putman and Jean Paul Beaujard from France, and Setsu Kitaoka from Japan. Father and son walked the streets of Europe with design teams, pointing out details, shopping at antiques markets for Art Deco and Wiener Werkstatte pieces—and arguing. Plans would be drawn and redrawn; sections would be built, scratched, and rebuilt. "They had very high standards . . . and kept changing their mind to make things more perfect," recalls Dick Blinder, of the design firm Beyer Blinder Belle, which supervised the construction of the store, designed to incorporate six elegant turn-of-the-century town houses. "Cost was no object, which was certainly very different than the way a public corporation would have treated it."

When the Barneys Women's Store finally opened, two years late and having cost more than $25 million, it was spacious and elegant, with a magnificent spiral staircase that winds up six floors and looks like something out of a Fred Astaire movie. Between the Prada bags and Andree Putman's checkerboard cosmetics counter (which stocked real tortoiseshell combs), shopaholics from Cher to Madonna could be spotted wielding charge cards. Sundays became a fashion sideshow, with pencil-thin models in leather trekking through the store with assorted downtown trendsetters. Standing on the corner, Bill Cunningham, the veteran New York Times photographer, captured it all.

"Most people play it safe and worry about last year's figures," says Donna Karan, "but Gene works from the gut."

Everybody got into the groove. "Barneys is like a decadent reward," says New York actress Sarah Jessica Parker. "If you're a decent person and you work hard, you get to go to Barneys." Everything at Barneys was younger and cooler. The clerks oozed more attitude than the customers. It worked. Barneys carried Miuccia Prada's clothes when the fashion press still laughingly termed them "Simplicity Patterns." Gene showcased then unknowns such as Azzedine Alai'a, Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garmons, and Helmut Lang. Jil Sander, another Barneys import, recalls her first meeting with Gene as "spontaneous love."

"Gene had the courage to take risks," says Alai'a, who regards the Pressmans as a second family. "He introduced a lot of new designers—not just me but also Rei and so many others—to America. From the beginning, he was very supportive."

"Gene is so confident," explains Chet Hazzard, president of Vera Wang. "He has a wonderful way of bringing designers he believes in into his world and Barneys." But if "his" designers wanted to expand beyond Barneys—say into Bergdorfs—Gene could go from charming to profane in the blink of an eye. "He can be unpleasant," acknowledges Hazzard. "And it isn't always fun to be on the receiving end."

"Sometimes they go too far," says Giorgio Armani, no stranger to battles with the Pressmans. "But whatever else you can say about Barneys, you must admit that it is one of the stores everyone watches."

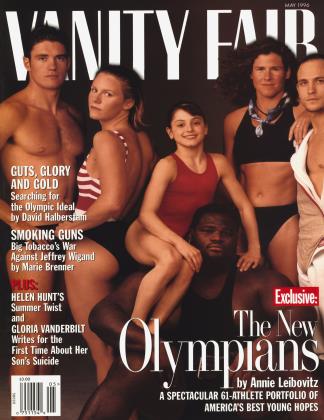

In the 80s, image was all. Nobody did it better than Barneys. Smart ads were a tradition pioneered by Barney Pressman, whose radio slogans included "Calling all men to Barney's." Gene carried the torch, assembling a dazzling creative team that featured the best names in the business—Neil Kraft, vice president of advertising; Ronnie Cooke Newhouse, a creative director; art director Fabien Baron; publicity director Mallory Andrews; copywriter Glenn O'Brien; photographers such as Annie Leibovitz and Steven Meisel; merchants Anne Ball and Connie Darrow. Together they orchestrated a retail identity of unparalleled eccentric urbanity. One memorable television ad showed a model sauntering down a Parisian boulevard to throatily utter, "Baar-nees." It was sophisticated, European, enticing. A later campaign features figures rendered by artist Jean-Philippe Delhomme, accompanied by inscrutable comments such as "Harold liked carpet surfing." The ads succeeded in creating the sense that Barneys was the cutting edge.

Adding to the mystique were provocative windows by Simon Doonan, a Brit with a tongue as sharp as his taste. His mischievous holiday displays (a Magic Johnson window complete with condom-festooned Christmas tree) were newsmaking and laced with in-jokes. Barneys, according to Doonan, attracted him because it was much more tolerant of his irreverent attitude than traditional stores would have been. "No one ever said to me, 'How dare you put condoms on a Christmas tree!' " he says.

"We wanted to make a lot of noise," recalls Ronnie Newhouse (now a member of the Newhouse family, which owns Conde Nast, publisher of Vanity Fair). "Fred and Gene had that kind of vision. It was like a combination of creative meeting and a men's locker room. Gene's a very male, high-testosterone character, and Barneys ads had a more macho sensibility than was typical of the fashion industry."

By 1989, Barneys was hot, grossing $100 million annually, according to its own figures. "There was very much a feeling in the 80s that it was a grand time to be there," recalls Glenn O'Brien. "We had all this talent, and were doing all these amazing things."

Wildly charismatic and willful, Gene made the scene in Milan with Armani and Romeo Gigli and dodged paparazzi while discoing in Paris with Azzedine Alai'a and a bevy of runway beauties. For the people he cultivated, his ego was compelling. "He is like the little boy with a curl in the middle of his forehead—when he was good he was very, very good, and when he was bad he was horrid," says a former vice president of the company. "He could make you feel like you walked on water, and inspired you. But you didn't want him as an enemy, because he could kill you with a look."

Just when retail seemed dead, as Bonwit Teller bowed and carriage-trade stores failed across the country, Gene Pressman—the ponytailed insurgent—made the business exciting again. "While everybody else has been closing stores, he has been opening them and in the process revitalizing whole communities," says Donna Karan, who swears that she really doesn't blame the Pressmans for her company's financial problems with Barneys. "Most people play it safe and worry about last year's figures, but Gene works from the gut."

Always high-profile, Gene married Bonnie Lysohir, a former Ford model, in 1982. Their Westchester home is a 100-year-old Tudor-style mansion which, Gene likes to boast, once belonged to mobster Bugsy Siegel. (It features a private dock, with a secret passageway from the waterfront to the basement, through which, according to legend, bootleg whiskey was once moved from ships waiting off Long Island Sound.) Gene hired architect Peter Marino, who had worked on the downtown store, to turn the house into a showplace, and he did, filling it with Wiener Werkstatte furniture, a 14,000-bottle wine cellar, and a cavernous garage for his collection of sports cars, including a vintage '62 Aston Martin and a '52 Mercedes Gull Wing.

To friends, Gene is by turns gracious and crass, obnoxious and endearing. At dinner parties, he's been known to brag about the price of a $200 Bordeaux, only to discover, while reading aloud from a wine almanac, that the bottle shouldn't have been opened for another five years. He likes nothing better than to take guests out on his cigarette boat, but often manages to run into trouble and has to be towed back. "Slamming across [Long Island] Sound with Gene are some of the most frightening moments of my life," says a friend. "Gene is never boring," confirms Carl Portale, the publisher of Elle and Mirabella magazines, who along with Vogue publisher Ron Galotti is one of Gene's golfing buddies. "He attacks the game the way he attacks life, with everything he's got."

Office work was not always tackled with the same avidity. Gene's habit was to buzz into town in his black Porsche and stride into the office around 10, puffing on a big Cuban cigar. (He kept a humidor in his trunk.) Most mornings he would disappear into the executive gym he had installed down the hall from his office, emerging in time to stick his head in at the end of a meeting before going out for lunch. He often held court at Le Madri, the handsome Northern Italian restaurant which the Pressmans and restaurateur Pino Luongo opened a block from Barneys as a sort of deluxe store cafeteria. (The Pressmans' two other ventures with Luongo, Mad. 61, in the uptown Barneys, and Coco Pazzo, are among the most popular power restaurants in the city.)

By the late 80s, however, Gene was at the store less and less. Unlike Fred Pressman, who still comes in on Sundays and goes from department to department rearranging displays and obsessing over small details, Gene was almost never on the floor. After he took up golf, he almost never came in on warm Fridays. "I think he thought he could schmooze his buddies and the store would be taken care of," says a former executive.

While Gene became the family star, Bob Pressman, socially awkward and somewhat brooding, was relegated to the darker region of the cosmos. (The men's two married sisters, Nancy Pressman Dressier and Liz Pressman Neubardt, both have company titles.) Bob, who graduated from Boston University and later earned an M.B.A. from Pace University, was given a position equal to Gene's on the numbers side of the business. He was, however, definitely seen as lacking in the trademark Pressman flair.

"His grandfather used to say Bobby had a good head for figures," recalls Martin Greenfield, a legendary tailor who dresses everyone from Arnold Schwarzenegger to President Clinton and has known the Pressman family for 45 years. "But Bobby doesn't have the sensitivity to the product, or to people, that you have to have to be good at this business."

The two brothers couldn't be more different. Where Gene is casual, Bob favors business suits, silk ties, French cuffs. Where Gene is fit, funny, and aggressive, Bob is pudgy, stuffy, and conservative. What they share is arrogance and volatility, qualities some trace to their strong-willed mother, Phyllis Pressman. She is known as a terror at the store, where she rules family along with Chelsea Passage, the gift salon specializing in Georg Jensen silverware and exclusive patterns of Porthault linens. "She could sit and abuse you for hours," says a former employee.

But Gene helped his wife, Bonnie, secure Phyllis's goodwill. Bonnie Pressman, who now heads Barneys' women's division, has become a favorite at the store, where she is widely regarded as hardworking and extraordinarily kind. According to Barneys sources, Bob's wife, Holly, is less favored by the store's sometimes not so sympathetic employees. A former Morgan Stanley money manager, she runs the boys' and young men's department.

According to store sources, Bob and Holly perceive themselves as completely in the shadow of Gene and Bonnie. Their resentment is obvious and painful to observe. "It had to be seen to be believed," recalls a former Barneys executive. "This is a family where there is a tremendous amount of jealousy."

From a Seventh Avenue sage: "It just goes to prove the old adage that the third generation always runs the empire into the ground."

Storeside, emotions run high with the often at-odds family members working together five days a week. Some employees describe the situation as a continuing melodrama in which family members haggle incessantly over titles, salaries, and authority. For example, when new headquarters were planned, measurements were taken to the last square inch to ensure that the two brothers' adjoining offices would be exactly the same size. When New York magazine planned to feature Gene alone in a major story on the opening of the Women's Store, Bob threw such a tantrum that at the last minute the magazine mechanically inserted him into the cover photograph beside his beaming brother.

Emotional scenes and rivalries are par for the course with all families and most family businesses. But at Barneys, according to one insider, the tensions between the two brothers have been endlessly exacerbated by their conflicts over money. Gene began costly improvements on the Women's Store almost immediately after its inauguration. The contemporary-clothes section, called the CO/OP, was closed just four months after its debut. When it reopened a season later, Gene told a reporter from Women's Wear Daily that he still hadn't finished fine-tuning. Asked when the store might be completed, he estimated another four or five years. Bob wearily added, "It's never finished."

This is a family in which no detail is too small to ignore. The brothers battled loudly and vocally over Gene's expenditures and his inability to stick to budgets, say insiders, and when Bob confronted Fred with the bills, his father, also an aesthetic perfectionist, sided with Gene. "We were always on the same page regarding budget matters," says Gene of his relationship with his father.

According to a source close to the Pressman family, "Fred has a blind spot for Gene. Gene cannot distinguish between fantasy and reality. This has been a problem since childhood. . . . Fred supported almost anything he wanted, regardless of its merits, consequences, or benefits."

"Between the brothers it was a constant battle," recalls an architect who worked for Barneys. "Bobby wanted to prove that he could do anything. No matter how outrageous Gene's plan was, he could come up with the financing. So maybe he's claiming it was all Gene's idea, but he was as much to blame. That's how it was between them."

By the late 80s, not satisfied with Barneys' downtown image, Gene was eager to take on the big department stores on their own turf. He had been obsessed with Bergdorf Goodman and its dapper chairman, Ira Neimark. A former Bergdorf's executive remembers Gene pestering him for details on how Neimark, then in his late 60s, conducted himself, what he was like in meetings, what he wore. "Gene would always scoff at him and make critical remarks, but he respected what he had accomplished," says the source, adding, "He wanted to knock him off his pedestal."

Years earlier, Fred had come close to buying the old Henri Bendel store on 57th Street. He had also toyed with the idea of opening Barneys in other cities. (He worried that few places could support such an upscale store.) Fred shared Gene's dream of moving uptown and allowed himself to be convinced. But the Pressmans' timing couldn't have been worse. They chose to embark on their ambitious expansion program in 1987, on the heels of the stock-market crash, when most retailers were preparing to cut back. It was the kind of decision that only a family-held company could make. Public companies are accountable to shareholders. The Pressman brothers were accountable to no one.

Back in 1982, one week before Gene's marriage, Fred had established an elaborate family trust encompassing all of the family's holdings. Fred got 25 voting shares, Gene and Bob got 25 each, and the two daughters got 12.5 each. As patriarch and chairman, Fred retained voting control of the company through his personal stock ownership and as trustee of the children's trusts. So it was with his knowledge and approval that the brothers went into action, opening their first branch store, in the World Financial Center, and a few months later announcing their intention of opening as many as 100 Barneys America stores across the country.

It was Bob's idea to bring in Goldman, Sachs & Co. to help map out a long-term strategic plan and locate potential investors. The Pressmans had already made the rounds of Wall Street, where they struck investors as willful and self-satisfied. Because the Pressmans, however, were reluctant to give up any control, they rejected traditional financing, such as a public offering. In November 1988, Goldman arranged a meeting with the then head of Isetan, Kuniyasu Kosuge, a brash, aggressive heir bent on making his own mark. Gene and Kosuge immediately hit it off.

Later, in March 1989, representatives from Barneys and Isetan met on a golf course in Hawaii. While Gene and Kosuge went out on the town, Bob negotiated into the early morning with Isetan's head of finance, hammering out an unprecedented international partnership which would provide the Pressmans with $12 million in expansion funds to build Barneys America stores in malls across the country. Isetan would hold a minority interest in the new American stores, a majority interest in all Barneys stores built in Japan, and, quite important, rights to the Barneys name in Asia.

But Gene, with his platinum tongue, continued to work on Kosuge, and before the meeting was over, the two companies expanded the arrangement to include a complicated real-estate deal. Isetan agreed to bankroll three showcase stores, in uptown Manhattan, Chicago, and Beverly Hills. As the deal was originally negotiated, Isetan would pay out $236 million for the land and the new buildings and receive a monthly rent based on the property value and sales volume of each location. The Pressmans would get their stores for free and they would retain total control. The two companies were so pleased with each other they actually specified on paper that the agreement could last 499 years.

"When Fred first got back he said it was a marriage made in heaven," recalls Martin Greenfield. His sons were crowing that it was far more, implying that they had taken the Japanese for all they were worth. "Bob walked around patting himself on the back, saying, 'We fucked the Japanese—we didn't give them anything,'" recalls a former senior vice president of the company.

"Fred Pressman has a blind spot for Gene. Gene cannot distinguish between fantasy and reality."

But some were ambivalent about the deal's long-term prospects. "Gene talked his way into this very strange agreement," says Tomio Taki, one of Barneys' largest suppliers, who owns Anne Klein and co-owns Donna Karan. "It was clear something would have to be done between the Japanese investors and the Pressmans down the road because the agreement was dramatically one-sided to benefit the Pressmans and Barneys."

As soon as the deal was done, Gene Pressman began scouting New York's best retail locations for Barneys' new uptown store. He eventually settled on 660 Madison Avenue, a property once owned by Jean Paul Getty. Peter Marino gutted the existing building and started from scratch, carving out a vast, 230,000-square-foot store on the first 8 floors, and 14 floors of premium office space above that. More than $20 million was spent blasting down through 15 feet of solid granite for a new basement to house a truck elevator and a special turntable to bring in merchandise in the heavily trafficked area. The Pressmans insisted on sheathing the entire building in French limestone, top to bottom—until the construction firm persuaded them to stop at the 10th floor, above which pre-cast concrete is barely noticeable. Expenses soared and the interior work had not even begun.

Although the agreement with Isetan specified the amount of funding available for the new stores, Gene and Fred ignored the budget from the beginning. Plans were drawn and scratched, drawn and scratched. Repeating a familiar pattern, Gene would visit the construction site and make changes. Then Fred would drop by and undo them. The process took on a surreal dimension when all six Pressmans were brought in.

Because Gene liked wood floors, 40 kinds of trees, from beech to sycamore, were used. Because he liked antiques, some of the chairs came from Christie's. Because he enjoyed aquariums, he had three large ones custom-built. (Eventually they would be stocked with expensive saltwater fish. A baby sand shark named Sinatra was removed after it began attacking its valuable tankmates.) There were additional whims. Gene planned a professional boxing ring for the lavish, never completed ninth-floor health club. Money was no object. A $15,000 light fixture was rejected at the last minute when Gene decided he hated it and ordered it dispatched to the warehouse. The elegant main foyer reportedly had to be redone after the original design allowed gale-force winds to whip through the spare corridors. Marino's bill swelled along with the family's competing eccentricities.

"Fred and Gene were at numerous meetings where Lehrer McGovern Bovis [the construction company] pointed out the cost overruns, and where the design ignored the financial realities of the deal with Isetan," says a source close to the Pressmans. "But they could not be prevented from building the store like their personal homes."

The constant changes put the company months behind schedule. "Ninety-nine percent of additional costs were related to design changes and overtime," says Michael Kaplan, vice president of Lehrer McGovern Bovis. "We worked from the middle of May to the morning the store opened 20 hours a day, seven days a week. It cost millions and millions in overtime." Making matters worse, Metropolitan Life, which had been developing office space in the floors above Barneys, abruptly backed out, forcing Isetan to put up another $120 million to protect its original $150 million investment in the building.

At the same time, construction of the Beverly Hills Barneys, featuring extravagant architectural flourishes such as an elaborate wrought-iron staircase and acid-etched glass, was also running way over budget. Because of a code violation, the Pressmans were forced by city officials to add an underground parking garage. The project ran between $40 and $55 million over budget, depending on whose figures you believe. In any case, it was a lot of yen. The Pressmans, Isetan's Johmori told Time, "were using money like water."

Meanwhile, the Barneys America stores were problematic. The basic concept behind the stores, as proposed by chief financial officer Irv Rosenthal, was to provide the Barneys cachet at a lower price. At the time many retailers were openly skeptical that the Barneys formula would actually dovetail with demographics outside Manhattan (as Fred Pressman himself had worried). To hype the Dallas store, Gene reportedly hired a fleet of helicopters to whisk 75 guests to the center of the Cotton Bowl football field. To no avail. Barneys' spare black-to-brown fashion palette was squarely rejected by the local ladies. There was also a fuss when in-store stylists refused to do "big hair."

The Pressmans do not seem to have ever considered halting the expansion, despite mounting evidence of trouble. The stores tended to open big, but sales would quickly drop off. By 1993, 12 franchises, from Short Hills, New Jersey, to Seattle, were open—and struggling. (The Cleveland branch has already closed, and Short Hills, one of the first to open, is still not profitable.)

"Barneys was like a combination of creative meeting and a men's locker room. Gene's a very male, high-testosterone character."

"To be titans in the retail business you have to have a monumental ego," says Richard Posner of the Credit Exchange, the Dun & Bradstreet of the apparel business. "But they were paddling against a bleak market, and ego won't get the customer in the store. They wanted to be the biggest and the best, and they went for the top. Hardheaded businessmen they are not."

Compounding the problem were the unexpected budget overruns. Gene couldn't live with the downmarket feel of the franchises, so he decided to do mini-versions of Barneys with Marino, undermining the whole idea of the lower-cost structure. "Gene was incredibly extravagant, and Peter fed into that," says Michael Ratner, president of Richter & Ratner, one of the renovation firms brought in by Marino to work on the branch stores. Some of the tropical woods, such as ipe, a Brazilian hardwood, came in small pieces or were not very durable or practical. Construction was always behind schedule, so the woods were sometimes laid down while still wet. When they dried, they shrank and left huge gaps between the planks. ' "As a result, a year after they were finished, some of the stores looked terrible," says Ratner. (Both Barneys and Marino maintain that a change in merchandising strategy brought about the redesign of the stores.)

Marino's renovation of Gene's WestChester home had also gone way over budget, and several construction companies had trouble getting paid. Fred Sciliano, the general contractor on the job, reportedly did $800,000 worth of work, but the constant changes and subsequent financial disputes left him no profit. In the end, he closed his business.

Says Gene Pressman, "All contractors were fully paid in accordance with their contracts."

By 1992 it was apparent that the Pressmans were not managing the new, bigger Barneys as well as they might. Bob, with Fred's blessing, hired the accounting firm of Coopers & Lybrand to identify ways the company could be restructured to accommodate growth and be made more profitable. It was also Bob, some months later, who insisted that Charles Bunstine be hired away from Coopers to become a senior vice president at Barneys. Last year, Bunstine was promoted to president and C.O.O., despite his lack of experience with large retail operations. Bunstine, however, did have the ability to serve as a buffer between Gene and Bob, who had all but stopped speaking. The door between their adjoining offices was now kept locked.

Bunstine was a backslapping corporate politician who knew exactly how to flatter Bob and impress Gene on the fairway. He took charge immediately, becoming the official liaison between the staff and the Pressman brothers, and in the process quickly alienated many loyal employees. Following his arrival, one longtime executive after another resigned. Bunstine, according to former employees, failed to grasp what had made Barneys special and seemed to feel that the expanded operation should become more conventional. The creative types revolted. "Charles is a know-it-all," says Glenn O'Brien, who quit after 10 years with the company. "Maybe he should be running for office."

The effects of the creative drain following Bunstine's 1992 arrival are still being felt: Barneys is currently short on talent. The advertising department, once so strong and innovative, hasn't featured a new, high-profile campaign for several seasons. Instead, Bonnie Solomon, a vice president of advertising who has risen rapidly within the company, has managed to alienate some members of the creative community. "Gene wanted to delegate a lot of stuff, but he delegated it to the wrong people," explains a former executive.

"Bobby wanted to prove that he could do anything. No matter how outrageous Gene's plan was, Bobby could come up with the financing."

Key personnel have been lost to Calvin Klein, J. Crew, Isaac Mizrahi, and Donna Karan. In the midst of the current crises, Pressman family members, now ubiquitous in the store, have been more sympathetic and complimentary than usual to all employees. But Barneys doesn't have even a full-time head of public relations. Wearing that hat, and countless others, is Simon Doonan, whose creative talents do not necessarily extend to spin control. Doonan's mere presence, however, is a testimony to Gene Pressman's continuing competitiveness and salesmanship. Gene reportedly talked Doonan out of taking an $800,000-a-year job at Ralph Lauren just weeks before the bankruptcy was announced.

No one was mentioning bankruptcy as the summer of 1993 faded, but there were rumors of financial trouble at Barneys even before the new Madison Avenue store was seen by the public. The rumors were true. The finance charges on construction loans, combined with $2-million-a-month lease payments to Isetan, were proving too heavy a burden. In Japan, Isetan—itself battered by recession—was in the hands of new management. Kosuge, Gene's generous buddy, had been covered with shame and kicked upstairs in May of 1993, ending an era of family management.

Kosuge's successor, Kazumasa Koshiba, was shocked by the Pressmans' spending. But he reluctantly advanced an additional $167 million to pay the bills. This time, however, he insisted on additional security in the personal guarantees from both brothers.

In the fall of 1993, the Madison Avenue Barneys opened with a party which drew celebrities ranging from Edgar Bronfman Jr. and his wife, Clarissa, to Spike Lee, Barbara Walters, Anne Bass, Blaine Trump, and Debbie Harry. After cocktails at the store, guests made their way through a secret passageway on the second floor into the Pierre. There the party continued with music by Barry White and the Love Unlimited Orchestra.

But the festivities were soon overshadowed; firms that had worked on the store were desperate for payment. Employees, frustrated by aesthetic dictates that kept them standing for hours on marble floors (sitting behind the counters was visually displeasing), laughed when Peter Marino was forced to lay off a quarter of his staff after the Pressmans failed to pay up. When The New York Times's Amy Spindler broke the story about Barneys' problems paying vendors, Charles Bunstine threatened to have her fired. "It was the most traumatic day of my career," she recalls. Bunstine's strong-arm approach, combined with the Pressmans' history of attempts to influence coverage, also backfired when the bankruptcy was announced. The press, free at last, took up Barneys-bashing like populists weaned on Wal-Mart rations. Maureen Dowd of The New York Times wrote a stinging column, lecturing about the dangers of "fiscal irresponsibility" and comparing Barneys to Universal's expensive and highly flogged film Waterworld.

The Pressmans' high-handedness fanned flames of resentment. The company's faxed Chapter 11 announcement expressed no apologies or regrets, even though the shortfall could close more than one small firm's doors. The last straw for some came when their frantic calls to the company for information about payments went unreturned. "The Pressmans' bravado was so unabashed, why shouldn't people throw brickbats at them now," says Alan Millstein, a leading retail consultant who has been critical of Barneys in the past. "They just screwed dozens of small suppliers. They left their Christmas bills unpaid. Everyone shipped their stuff in good faith, and they're probably not going to see a penny of it. It's tragic."

"They owed me $900,000 for over a year," says Michael Ratner, who claims he phoned every day for six months without ever receiving a return call. When Ratner ran into Gene, "he looked right through me, like I wasn't there," recalls Ratner, who filed suit and eventually was paid. "It's the arrogance that gets you."

Barneys says it intends to pay its vendors, but for some it is already too late. Manolo, a former milliner whose resortwear collection was purchased by Barneys, says that he closed his business after the store fell six months behind in its payments to him, and that 50 of his calls to Barneys went unanswered. "I felt pushed around and ignored," Manolo says. Ultimately he was paid-after a New York Times reporter picked up on his predicament. A Barneys executive brought Manolo the check. "She put it on the bench between us," Manolo recalls. "She said she wanted me to retract the statement I had given The New York Times. Then she would have no problem paying me." (Barneys says that Manolo's account is totally inaccurate.)

"The Pressmans built an incredible, quality institution. If they've lost the store, it will be very sad."

At Christmas, Gene Pressman treated his family to a lavish vacation in Hawaii. When he met Tomio Taki for a round of golf at the Honolulu Country Club, he never let on that anything was wrong. "I think he was in denial," says Taki, whose company is one of Barneys' largest creditors. "Gene, and everyone in the company, was living on hope."

But the well had finally run dry. Isetan had cut off the flow of funds. To cover the cost overruns, the Pressmans made the rounds of banks and managed, in a period of 18 months, to borrow nearly $170 million. Now swamped in debt and unable to make payments to Isetan, the Pressmans decided at a board meeting on December 20 to officially file for bankruptcy-court protection.

If Barney Pressman could know what has become of his store, "he'd turn over in his grave," according to his widow, Isabel Pressman. Barney died in 1991 at the age of 96. For Fred, now 73 and gravely ill, the bankruptcy of his family business must be devastating. A salesman to the last, however, he comes into the store every day and has taken an apartment at the Regency Hotel so he doesn't have to commute. A small, slender man who has worn the same rumpled Burberry for years, he is still going up to the showrooms to feel the fabrics and look over the fall lines.

"He came up a few weeks ago, and you could feel his suffering," says Joe Barrato, C.E.O. of Brioni U.S.A., whose family has been doing business with the Pressmans on and off for 30 years. "The Pressmans have a spirit some people call it an attitude. Some like it, some don't. But they built an incredible, quality institution, and they've remained a family business a long time. Barneys wouldn't be Barneys without them. If they've lost the store, it will be very sad."

And very nasty. The two brothers are speaking again, but only because they have to. Bob, according to a family source, believes he is being set up by his brother as the fall guy since he was technically in charge of finances. But because of the way the family trust is structured, no one had the power to act alone. Gene and Fred presumably had to sign off on the loans Barneys obtained. In an attempt to head off disaster, Bob made numerous trips to Tokyo—without Gene—in 1994 and 1995. A source close to the Pressmans claims that Bob tried to persuade the Japanese to convert their investment and the loans personally guaranteed into equity equaling up to 49 percent of Barneys. Gene had opposed giving Isetan equity. But, according to the source, "Bob convinced Fred to pressure Gene to agree."

Barneys' current suit is essentially an attempt to enforce the equity agreement, which Isetan denies ever making. Its lawyers at Hughes Hubbard & Reed say that a March 1994 document, used as evidence of an equity solution, is merely a statement of Barneys' willingness to discuss such a solution. They say that it was, in fact, Isetan which demanded the commitment from Barneys. Isetan's position is that they own the three showcase stores in New York, Beverly Hills, and Chicago, and they expect the Pressmans to pay rent and repay the $170 million in loans which were personally guaranteed.

For the time being, it is business as usual for Barneys. But for how long? The Oscar-night parties planned with Entertainment Tonight for Mad. 61 and Barney Greengrass, the store restaurant in Beverly Hills, were canceled, and, with Barneys vulnerable, Pino Luongo (who has reportedly wanted out of his restaurant partnerships with the Pressmans for some time) has taken ownership of Coco Pazzo and Le Madri and has given Barneys ownership of the far less prestigious in-store restaurants at some Barneys franchises. In the stores themselves, the racks are still filled with impossibly hip black clothes. With the court cutting the checks, most designers are shipping their lines, though they don't know how much of their earlier losses will be recovered. Incredibly, the Pressmans snagged new loans of $120 million from Chemical and other lenders. But Seventh Avenue has the jitters. In late March, Republic National Bank, owed in excess of $25 million, sold its loan to a "vulture fund." The private debt broker paid a reported 38 cents on the dollar.

But, even though they are furious, Isetan, which has hundreds of millions of dollars at stake, doesn't want to see Barneys disappear. "It's a great institution and it should continue," says Isetan's counsel Howard Kaufman, a partner with Hughes Hubbard & Reed. "But perhaps not with the Pressmans running it."

By late spring, it is possible that the Pressmans could be out of the store they built—forever. And despite their assurances to the contrary, it is almost inevitable that some Barneys stores will have to close.

Sources at Isetan say that the current standoff might have been avoided if the Pressmans hadn't been so continually and unrepentantly arrogant. "If they had reacted reasonably, and said they were sorry, it would be one thing," says a source close to Isetan's management, "but they have never apologized to the Japanese." Barneys says that it made repeated attempts to negotiate a solution, but that "it was the financial equivalent of eating sushi with one chopstick."

Carl Portale, who spent the holidays in Hawaii with Gene, says Pressman has not been humbled by recent events. "He's still holding his head up high," marvels Portale. "He beat me in a round of golf on December 29. He shot an 82. When I found out afterward [about the bankruptcy], I thought it was absolutely incredible. He was so cool."

Why not? Gene Pressman is still thinking big. When an advertising executive asked him how he was doing, Gene just shrugged and said, "Now I'm more famous than ever."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now