Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

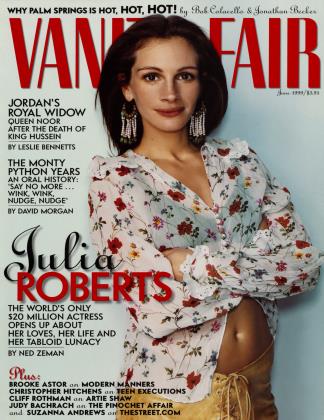

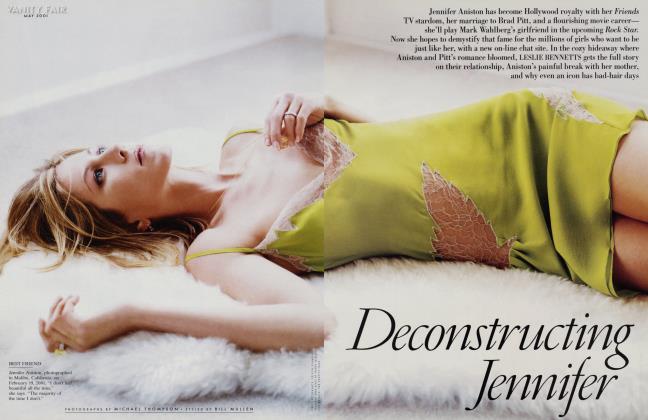

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe death of Jordan's King Hussein from cancer in February left gaping holes both in the delicate political structure of the Middle East and in the heart of his beautiful, American-born wife, Queen Noor, who now carries a nation's grief into sleepless nights and poignant dreams. At the palace in Amman, LESLIE BENNETTS talks with Noor about the transformation of a free-spirited girl named Lisa Halaby as she navigated a whirlwind 1978 courtship with the thrice-married Islamic monarch, years of vicious criticism from her adopted people, and painful rumors about her son's place in the royal succession

June 1999 Leslie Bennetts Herb RittsThe death of Jordan's King Hussein from cancer in February left gaping holes both in the delicate political structure of the Middle East and in the heart of his beautiful, American-born wife, Queen Noor, who now carries a nation's grief into sleepless nights and poignant dreams. At the palace in Amman, LESLIE BENNETTS talks with Noor about the transformation of a free-spirited girl named Lisa Halaby as she navigated a whirlwind 1978 courtship with the thrice-married Islamic monarch, years of vicious criticism from her adopted people, and painful rumors about her son's place in the royal succession

June 1999 Leslie Bennetts Herb Ritts'The only question I can't answer is 'How are you?,"' Queen Noor tells me with a rueful smile on my first day in Amman. "I don't know how to answer that."

So how is she? "Soldiering on, as I must," she says. "Right now I'm taking each day as it comes. It's new territory."

A statement like that is typical Queen Noor: pious, dutiful, self-contained. The official 40-day mourning period since the death of her husband, King Hussein of Jordan, is nearly over, and the queen has maintained an unshakable composure throughout as she received thousands of visitors offering condolences. By day, she looks so serene she appears almost beatific, and her dignity and self-discipline have won high marks from Jordanians. "People have completely changed in their view of her," one wealthy Amman woman says. "Before, people resented her: 'She'll never be Arab!' Now they're in awe of her and the way she's handled herself during the condolences. They say, 'She's more of a queen than if she was born a queen!' She portrayed Jordan very well to the rest of the world, and to Jordanians that's very important."

The queen's private reality is another story; her emotional state is painfully variable. "It changes all the time," she says quietly. "The feelings come and go every day."

When she sleeps, she relives her husband's harrowing months of cancer treatment. "I dream this struggle every night," she confesses. "We're still in the midst of fighting, my husband and I. We're together, with all that hopeful, faithful spirit. Then the realization sets in as one surfaces from the dream."

I wince, and she quickly reassures me, as if I were the one who needed to be consoled. "It's not traumatic," she says. "It's: Oh, we've moved beyond that struggle; now there's a new challenge."

When we start talking about denial as a coping mechanism, she says wryly, "There is obviously an aspect of that in all of this. But that presumes that at some point I crash and burn. I couldn't be living in denial, because I'm with people every day who make this real for me. I have to transcend my own personal feelings to comfort them, and that helps me to focus outside myself."

Maintaining such self-control is nothing new. "All these years, I have had to," she says. "In my husband's position, he always felt that his responsibility was to project only the most positive, constructive, caring, loving, comforting spirit to everyone he encountered, no matter what he was feeling inside. It was easy to see that that was one way of giving the best of oneself to others, and also it happens to be a very peaceful way to live your life—to whatever extent you can do it."

When I comment that only a saint could consistently meet such a standard, she says hastily, "I don't think of myself as a saintly person. I'm talking about a formula that works in my life, that I have learned from my husband's example, and that I have been fortunate enough to find a measure of peace in at some of the most agonizing times of my life." She allows herself a small sigh. "But it is work."

And Queen Noor works hard at it. "I didn't say I don't have tears, but I try to keep those to myself as much as I can so I don't burden others," she says. "So I keep my own agony to myself. But there are moments ..."

We are having lunch on a sunny patio outside her white-walled limestone palace, Bab Al Salam, which is on the outskirts of Amman. Agony notwithstanding, today she looks radiant. All morning she received visitors in the main parlor, whose coffee table holds a velvet box containing the satin Jordanian flag that was draped over His Majesty's coffin, alongside his red-and-gold Koran and an array of elaborately engraved daggers. Reed thin, she wore a formfitting black suit with a skirt that swept her ankles, with elegant black stiletto heels peeking out from underneath; her most visible concession to Islamic tradition was the white yanis, or scarf, that covered her head. Gracious and warm, as if she had all the time in the world, Queen Noor shook every hand. "She's so beautiful!" marveled one American woman moving through the receiving line to meet her. "We're the same age, but she looks fabulous!"

For lunch alone with me, the 47-year-old queen had changed into black jeans and an embroidered twinset that showed her lithe body to best advantage. With honey-blond hair framing her glowing face and her eyes sparkling a bright cerulean blue, she could be a Western movie star rather than an Islamic queen.

But four days later, after the private family ceremonies marking the end of the mourning period, the change is shocking. Her face is haggard, pale, and deeply lined; she looks 10 years older. Even her eyes seem bleached and colorless, her eyelids puffy. When I ask if she's been sleeping, she looks guilty, as if I had just unearthed a shameful secret. "I haven't slept in three nights," she admits.

Although her tone is devoid of self-pity, such a personal admission is rare. Six months ago, when I first spent time with Queen Noor in the United States, she was working hard to maintain her usual impenetrable facade. The simplest question elicited numbing streams of verbiage. Inquire about her feelings and you would get a monologue on Middle Eastern politics, or on Western misconceptions about the Islamic religion, or on her efforts to encourage Jordanian development—anything but her own personal experience. Her sentences are interminable and use as many multisyllabic words as possible. Despite their complexity, they parse correctly— Queen Noor is so deliberate about all she does that sloppiness in speech would be as unacceptable here as in everything else. It is clear that Queen Noor uses language as a shield, both to prevent her real feelings from leaking out and to prevent others from discerning them. "Here's a woman who's been thrust into an incredibly difficult role, under the microscope all the time, so she's schooled herself how to behave in a way to protect herself," says Marion Freeman, a former classmate from Concord Academy and Princeton who now owns a software company with her husband. "She can't afford to get into trouble."

But the last year has been a torturous emotional roller-coaster ride for the queen and her four children, and the immense loss she just suffered has left her more vulnerable, and therefore more accessible, than usual. A scant 12 months ago, the family celebrated their final moments of transcendent happiness with a gala at their 60-acre English country estate near Ascot, honoring both the 20th wedding anniversary of the king and queen and the 18th birthday of their elder son, Prince Hamzah. The guest list reflected the glamorously eclectic nature of their friendships: from Prince Charles, King Constantine of Greece, and King Juan Carlos of Spain to Harrison Ford, Barbara Walters, and Oscar de la Renta to Queen Noor's closest friends from school, back when they knew her only as a tall, stunning American girl who looked as if she had just stepped out of a Ralph Lauren ad.

"I try to keep tears to myself as much as I can," says Queen Noor.

But within weeks, King Hussein was diagnosed with a recurrence of the non-Hodgkin's lymphoma he had battled successfully in 1992, when he lost a kidney. In July he began intensive chemotherapy, followed by a debilitating bone-marrow transplant at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, with the queen always by his side; when she slept, it was in the hospital room next to his. November marked the king's 63rd birthday; by December, he had been pronounced in remission, and in January the king and queen returned home to Jordan to a tumultuous welcome.

"For us, he was God on earth," one Jordanian told me. "We thought he was immortal."

In a freezing rain, King Hussein rode triumphantly through the streets of Amman, standing up through the sunroof in his car, waving to the hysterical throngs. But within days his fevers had returned and he was back at the Mayo Clinic for a last-ditch effort to save his life. A second bone-marrow transplant failed, and by the time the king was flown home to Jordan for the last time, he was heavily sedated and on a respirator. He died on February 7, ending an extraordinary 47-year reign, during which he had become one of the longest-ruling monarchs in the world and developed his fledgling kingdom into a modern nation that had won respect as the most stable country in the Middle East. His subjects were devastated; even his opponents wept, and two people tried to commit suicide in Amman on the day he died, one of them successfully.

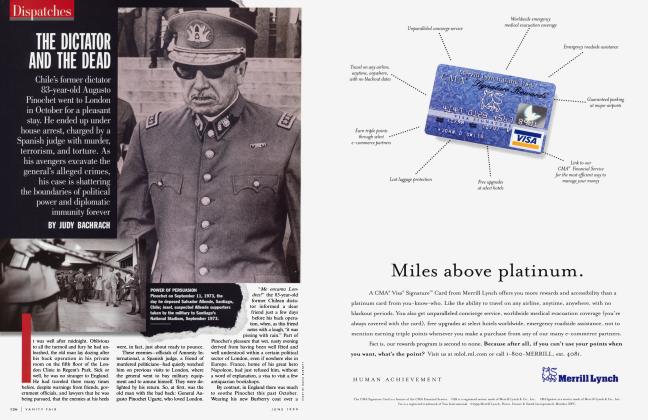

Only days earlier, King Hussein had shocked the Jordanian people by abruptly changing his line of succession. For 34 years King Hussein's brother Prince Hassan had been the crown prince, next in line for the throne. Unlike Hussein, Hassan was never considered a charmer—"No one seriously dislikes him, but he's a big, fat pompous bore who speaks with a pretentious British accent," one Middle East expert told me—but at least he was a known quantity.

In the final days of his life, King Hussein wrote his brother a letter that was both sorrowful and angry; he accused those around Prince Hassan, if not the prince himself, of disloyalties that included having spread vicious gossip about Queen Noor. The Jordanian people had always expected Prince Hassan to be their next monarch; they also knew that the handsome and charismatic Prince Hamzah was his father's favorite son. "The king saw himself in Hamzah," says Mohammad Al-Adwan, a former chief of protocol. "I think he always had Hamzah in mind."

But to almost everyone's astonishment, King Hussein announced that his eldest son, Prince Abdullah, would succeed him instead, with the understanding that Prince Hamzah would become the new crown prince. This decree prompted the usual round of rumors: that the Americans had engineered it; that the Israelis had engineered it; that the British had engineered it. Although the 37-year-old Abdullah was a career army officer who had become the country's chief military envoy, the Jordanian people had rarely heard about him. "We don't know him," one Jordanian banker told me worriedly. But now Abdullah is king, and Hamzah, who is studying at Sandhurst, the British military college once attended by his father and Winston Churchill, is next in line for the throne.

Right now all four of Queen Noor's children are in Amman. Prince Hamzah has flown home for the private family ceremonies marking the end of the official mourning period, and his younger siblings—17-year-old Prince Hashim, 16-year-old Princess Iman, and 13-year-old Princess Raiyah—have been here since their father's death, although they will soon return to schools in the United States. Two days after the mourning period ended, Queen Noor made her first public appearance, visiting children in the cancer wards of three Amman hospitals. Unexpectedly, when we returned to Bab Al Salam, King Abdullah had stopped by to meet with the queen behind closed doors. As we finally sit down to a late lunch, she seems unruffled, but a few days later—when King Abdullah names his own wife, a beautiful 28-year-old Palestinian named Rania, "Her Majesty, the great Queen"—I wonder whether that was when Noor got the news that she was being relegated to the status of queen mother.

Now it is late afternoon, and she and I are in a cozy sitting room off the main parlor, next to a crackling fire. It has been a bleak, unseasonably cold spring day, with intermittent rain—something drought-stricken Jordan needs desperately. As we make our way through a leisurely lunch of lentil soup, hummus, and crunchy pistachio pastries, the queen scarcely picks at her food. Despite the lack of sleep, she began her day on the treadmill, as usual, but she still looks bleary-eyed and ravaged. Suddenly there is a staccato rapping on the French doors that lead to the lawn. (Although it is springtime, little else in this desiccated city is green, but the queen's palace is surrounded by thick carpets of emerald grass and tinkling tiled fountains—perhaps the ultimate luxury in an arid land that is 90 percent desert.)

We look up, startled. Outside the doors are Prince Hamzah and Prince Hashim. The queen brightens; by now we have been talking for hours, and she thinks her children have come to claim her. But no: the princes confess that they were momentarily locked out of the house, and just looking for a way back in. Both are good-looking young men, but Prince Hamzah is taller, his features more finely chiseled. He is clearly a heartthrob; already Jordanian matrons squeal and quiver with excitement when they pass his car, as if he were a rock star.

For months, one of the leading rumors swirling around the palace was that Queen Noor was lobbying her husband to name Prince Hamzah as his successor. Since Noor was King Hussein's fourth wife, and he already had eight children when he married her in 1978, the dynamics of this particular royal family are byzantine even without the question of succession, which raised palace intrigue to Shakespearean proportions.

It had always been clear that there was no love lost between Queen Noor and Prince Hassan's wife, Princess Sarvath, who are widely believed to loathe each other. During the long, anxious months of the king's illness, Prince Hassan's court was blamed for a scurrilous whispering campaign that revived outlandish but persistent rumors about the American-born Queen Noor: that she had had an illegitimate child; that the child was black; that she was an extravagant spender who squandered millions of dollars on jewelry abroad despite the poverty of the Jordanian economy; that she was secretly a tool of the C.I.A.; that her children were on drugs; even that the queen—a towering blonde who has Arab blood on her father's side but whose mother is Swedish—was really Jewish, the ultimate insult in the Arab world. During King Hussein's cancer treatments, Princess Sarvath was also perceived as behaving as if her husband's succession were a fait accompli. She was even accused of redecorating the king's offices. "Very tacky," says one Jordanian official. "Both of them acted as if the king was going to die—and as if they didn't care."

"I had imagined we could have had another 15 or 20 years together,'' Queen Noor says sadly

But even from Minnesota the king was paying close attention, and in his final letter to Prince Hassan he made his bitterness explicit: "My small family was hurt by slander and falsehoods and I refer here to my wife and children.... I attributed it to the tendency towards rivalry among those who pretend to be faithful to you." King Hussein was also angry about Prince Hassan's longstanding refusal to promise that, if he became king, he would name Prince Hamzah as crown prince: "You were completely opposed to this until the time you would have assumed the throne and decided who would have been your successor."

So when the king finally chose the presumably more compliant Abdullah (in accordance with the Jordanian constitution, which names the eldest son as the monarch's heir), many observers perceived Queen Noor as having lost a high-stakes power struggle. "If there was a battle between Noor and Hassan, neither of them won," one Jordanian commented to me. "The unexpected happened: Abdullah came up like a jack-in-the-box. He was somebody no one ever speculated about."

Friends report that Prince Hassan, while resigned to his fate, is both grief-stricken and bitter, feeling unjustly accused. Although palace sources acknowledge that there was indisputably a "propaganda campaign" against Queen Noor, she herself will not say anything negative about Prince Hassan or her sister-in-law. "We're family," she says evenly, as if that covered everything.

The same goes for her various stepchildren. Palace insiders recall that, despite the queen's efforts to include them in family gatherings, she was often rebuffed by her stepchildren, many of whom didn't like her. But the queen refuses to admit to any such problems. How is her relationship with Abdullah, her new king? "It's very close," she says. "We've spent 21 years as members of one family. I've watched him grow and develop. These days we talk a lot. The one thing I desperately want to ensure is that he is never burdened or pressured by me in any way."

Most Jordanians still believe that if the king had had more time he would have effected the necessary changes in the Jordanian constitution to make Prince Hamzah his heir. But Queen Noor insists that the rumors about her cutthroat behind-the-scenes campaign are ridiculous. "The only indication I ever gave to my husband of what I thought the succession would be is what he thought was right—and that I would support whomever he chose, whatever their feelings about me," she says. "My husband made his feelings about our son very clear on his own; it didn't need to be encouraged or promoted by me. The irony is that I urged my husband to give Hamzah a chance to complete his education, and to have some time free of the inevitable pressures that would have been the result of his having institutionalized him in a position. I never once in our entire marriage suggested it." She pauses. "No one will believe this," she adds resignedly.

As for how things turned out, she takes a determinedly Panglossian view. "My husband had the most amazing instincts," she says. "I just knew that whatever decision he made would be the right one, and whatever was best for the country was what was needed. Whenever this subject reared its head, I counseled his children, my children, his nephews and cousins to simply have faith; it would be as God willed."

The queen's public posture is always thus: that the king was the most extraordinary of men, and that his wisdom was so exceptional he was virtually always correct. "I was so lucky to love and be loved by him, and that never dies," she says softly. "His photograph is beside my bed, and it makes me smile. I start my days talking to him; I end my days talking to him. His spirit is still guiding me." She isn't certain what she thinks about an afterlife, but she has a strong sense of the king's presence: "My feeling is that my husband's spirit is an enduring one, and that is an enormous comfort."

Now that he is gone, many foreigners seem to assume that Queen Noor will adopt a more international lifestyle. She is rich, beautiful, and relatively young; she moves easily between East and West; and one can readily envision her new life as a mixture of good works and jet-set glamour. Before the king died, she had already taken on Princess Diana's role as patron of the Landmine Survivors Network, a Washington-based group dedicated to the eradication of landmines and to the aid of their many victims around the world. The extent of the queen's financial resources is somewhat mysterious; notably resource-poor, Jordan is not a rich country, but the king was believed to have amassed a substantial personal fortune. "How rich was he? Nobody knows," one member of a rich Jordanian clan says dryly.

Although the queen can surely live however she pleases, she seems startled that anyone would even consider that she might distance herself from Jordan. "This is my home; this is my family," she says firmly. She refers constantly to "my work," and has no intention of cutting back on her commitment to public service. She sees her purpose in life as carrying on her husband's legacy, and King Abdullah has already named her head of the new King Hussein Foundation, which will support Jordanian development and peace-related efforts in the Middle East. And on a personal level, she honors her husband by trying to emulate his humanity.

"The word 'role model' isn't adequate here," she says. "One of the things that has not been well understood about my husband was the importance of his religious faith. As a Hashemite, as a descendant of the prophet Muhammad, he felt a huge burden of responsibility to be exemplary in his life and his relations, and it was one of the critical lenses through which he looked at everything he did. He never lost his faith in humanity; he never put up barriers that would have prevented him from looking for the best in people; he never became bitter.... Throughout his life, in spite of so many disappointments and so many cruel personal and political deceptions, he still maintained his faith and optimism about people."

She looks down at her hands, which are unadorned except for her own and her husband's wedding rings on one hand and, on the other, a ruby ring she gave him for his last birthday. "I'm a much better person for having known him," she says. "I have been sustained by feeling so fortunate—more than feeling deprived or bereft. I feel my life will always be enriched by his spirit."

Over the course of his long reign, King Hussein survived nearly a dozen assassination attempts. "His enemies strafed his home, shot at his plane, poisoned his food, even put acid in his nose drops," as Newsweek put it.

"He knew every day of his life, and I knew from the day we became engaged, that every moment was precious, and that anything could happen at any time," Queen Noor says. "From that moment, I would have been willing to give my life for him. We all would, because he represented something so much bigger than what we represented in our own lives."

She gazes beyond me to the garden outside the French doors, chilled now by a raw wind. "I had imagined we could have had another 15 or 20 years together," she says sadly.

Months earlier, on a brisk autumn afternoon, Queen Noor and I had sat on the terrace of her house in a Maryland suburb, talking about the life that had led her to Jordan. Before us was the Potomac River, half hidden behind trees that were just beginning to lose their leaves; the house was full of handwoven Jordanian rugs and pillows, and the table was set with colorful hand-painted Jordanian pottery.

King Hussein had just been summoned from the Mayo Clinic to Washington to help broker the Wye River peace accord between Israel's Benjamin Netanyahu and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat. The king and queen had been up all night, and the air crackled with tension as they waited for the call from the White House reporting that the agreement was ready to be signed. When it was, later that day, King Hussein would be credited with having played a critical role as mediator.

At first glance, Queen Noor seems an unlikely wife for a pint-size Middle East potentate.

Her father, Najeeb Halaby, is a prominent Syrian-American who served as head of Pan American World Airways, but although the former Lisa Halaby has always emphasized her Arab blood, in truth she is only one-quarter Arab. Her Swedish-American mother was pained by Queen Noor's repudiation of her Scandinavian background. "My mother has resented terribly that I find my Arab roots much more interesting," the queen says.

But to the young Lisa, Arabia had always represented the exotic, the unknown, and after earning a B.A. in architecture and urban planning from Princeton in 1974, she set off for the Middle East. She was searching for her heritage; she found her destiny.

Until she came along, King Hussein hadn't had much luck with his wives. He had become king under tragic circumstances. When Hussein was 15, his grandfather King Abdullah was assassinated by a Palestinian nationalist in front of his eyes; Hussein was shot as well, but a medal on his chest deflected the bullet. His father then became king, but was soon forced to abdicate because of schizophrenia. Hussein was only 16 when he ascended the throne.

His first wife, Princess Dina, was an older cousin he wed in an arranged marriage when he was 19. They managed to produce one daughter before divorcing. The king's second wife was Toni Gardiner, the daughter of a British military officer. A middle-class girl who had gone to secretarial school, the moonfaced Gardiner was given the name Princess Muna—"the king's desire"—by Hussein, and the sobriquet of "the typist from Ipswich" by derisive Jordanians. Princess Muna bore the king four children, including Prince Abdullah, who shares his mother's soft, round face. But 11 years later, the king, who always had a racy reputation as a playboy, divorced her to marry a 24-year-old Palestinian beauty who was the first of his wives to be awarded the title of queen. Queen Aha had two children and adopted a baby whose mother had been killed in a plane crash, but she herself died in a helicopter crash only five years into their marriage, plunging the king into deep depression.

Little more than a year later, Lisa Halaby appeared on the scene. After a whirlwind courtship that amazed both of them, she and the king got married in 1978. "She was totally in love with him," says her sister, Alexa Halaby, a lawyer and clinical social worker who lives in Washington, D.C. "It was clear how much he adored her. They just both viewed it as fate."

In marrying Hussein, the spirited, opinionated American gave up an extraordinary amount: her name, her religion, her country, her future as an independent woman. As her former classmate Marion Freeman puts it, she even gave up "the freedom to be able to have a bad hair day."

But to hear Queen Noor tell the story, none of these were sacrifices. First the king changed his bride's name to Noor al-Hussein—"the light of Hussein." The meaning of her name "was a generous gift from him," she says. Nor did she mourn the loss of her original identity: "I was never comfortable with the name Lisa. I never felt it was me."

She didn't even find it wrenching to convert; although her sister describes the family as "nominally Episcopalian," Queen Noor says, "I couldn't accept the dogmatic side of Christianity."

Islam means submission to the will of God, and the queen became adept at the art of submitting: to Islam; to her husband, the king; to the excruciatingly restrictive role of an Islamic queen; to the often archaic expectations of the Jordanian people. Jordan is, after all, a country where men still practice so-called "crimes of honor": even if a woman is raped, let alone if she gets pregnant out of wedlock, her father or brother may kill her, believing that she has disgraced the family and that its honor can be restored only by slaughtering her. The queen has spoken out against "honor" killings, but in general her demeanor is finely attuned to suggest humility and submission to local norms, and she frequently ends her sentences with the Arabic expression inshallah, which means "God willing." When Noor became a Muslim, says Marion Freeman, "I think she really gave up the Western idea of being in control. She accepted the Arab way of looking at things; there is a sense of fatalism, a sense that things happen in life because it is the hand of Allah."

However, sometimes the queen's acquiescence is more apparent than real. After her husband's death, the press made much of the fact that the queen had not been able to attend his funeral because Islamic tradition excludes females from such occasions. This, she now confesses, is not true. "I attended the funeral," she says quietly. "I watched my husband laid to rest, but I was not in the group of men. I was a few meters away. I did it out of sight. The custom here is that women do not attend, but I did. It was important to me to go through the entire process."

As a grieving widow, she is also mixing the traditional Western black with white, the Islamic color of mourning. "My husband hated mourning black with a passion, so I've tried to break it up and strike a balance—which is the way we lived our lives, striking a balance for our own principles while at the same time not being insensitive," she says.

Queen Noor has become a master at such exquisite calibrations. Her husband provided an eloquent example in the way he handled his own responsibilities; he had long walked a slender tightrope, buffeted by the warring rivalries of Israel, Syria, Egypt, and Iraq, with American and British interests to placate as well. As U.S. State Department analysts used to say, "Hussein doesn't sit on the fence—he is the fence." But by all accounts, the king didn't tell Noor how to be queen; he simply let her figure it out on her own. "He kind of threw me in the deep end," she says. "There is no official role for a queen in this country. It's whatever you as an individual choose to make of it."

Developing a public persona was particularly painful; Queen Noor had always been "pathologically shy," she says, and she was petrified of failure. "I always placed an incredible pressure on myself, because of feeling I had to be perfect in order not to let my husband down and not to let the country down." Realizing what a constructive role she could play as a bridge between East and West—one that became critically important when U.S.-Jordanian relations were strained to the breaking point during the Gulf War—she started to give speeches in America and abroad. "I was terrified of making a mistake that might cause problems for my husband or for Jordan," she says. "Every time I got up to speak, I felt I had the weight of the Arab side of the whole Arab-Israeli conflict on my shoulders. Which, of course, is not true; I magnified it out of proportion, I'm sure. But one little error could have blown up and caused the wrong problem at the wrong time."

The role Queen Noor evolved for herself has been as exemplary as it was unprecedented. She has pioneered a wide range of development efforts aimed at women's economic empowerment and the preservation of Jordanian handicrafts by funding pilot projects and promoting native products that range from hand-painted ceramics to Bedouin rugs. Her Noor Al Hussein Foundation, the umbrella organization she established for her varied concerns, has supported community-development, child welfare, education, and cultural-heritage initiatives, including the creation of the annual Jerash Festival for Culture and Arts, which has become a major event in the Arab world.

But no matter how worthy her causes, Queen Noor has always been the target of nasty gossip, particularly among what Amman society sardonically refers to as "the chattering class." "The king is the center of power, and there's jealousy: 'Why should she be his wife? Why shouldn't my daughter be his wife? She shouldn't be off doing all these things! She should stay home and take care of the kids!"' says one Jordanian journalist in trying to explain some of the animosity.

A wealthy Jordanian wife says, "Especially in the upper class here, women don't work. Maybe she made women feel insecure because they're not as effective. The feeling was 'She's not one of us.'"

The gossip tended to focus on trivialities. "They started talking about her shopping," says Mohammad Al-Adwan, who has served in many high government posts. "People were really unfair to her; they made her sound like Imelda Marcos. She dresses nicely, but most of the time here she wears Jordanian clothes that don't cost much. She and His Majesty lived more simply than many Jordanians."

The political context of a repressive monarchy also played a role. "They criticize the queen because they don't dare criticize the king; it's against the law—you can go to jail. So it's a way of criticizing the king," explains an influential Jordanian.

The queen has cultivated a philosophical attitude toward the slings and arrows: "A lot of it was based on some delusions about what a great life this is. I used to say to my husband, 'You wouldn't wish this job on your worst enemy—unless they were the right person for it.'" But, as usual, she simply soldiered on: "I constantly reminded myself that, if my husband could get through what he had to get through, I could get through what I had to get through—and that it wasn't personal."

In truth, sometimes it was all too personal; particularly hurtful were the intermittent rumors about the king's womanizing. Here again the queen found denial to be useful. "She ascribed most of whatever was in the media to malicious rumor," says Marion Freeman. "She trained herself not to give it any credence."

Even without outside criticism as a prod, Queen Noor holds herself to notoriously high standards. "I'm unbearable to my staff," she says with a smile. Before she delivers a speech, she will agonize over every word. "She's a perfectionist," says Marwan Muasher, the Jordanian ambassador to the United States. "She would go through 15 or 20 drafts of a speech; she wanted to make sure every sentence was right. She's a very articulate speaker, she has served very effectively as a spokesperson for Jordan, and she has become well known internationally in her own right, not just as the wife of the king."

Oddly, one topic Queen Noor can't seem to address is the moral implications of marrying a king in the first place. I am curious about how an American raised in a democratic society justifies becoming part of a political system in which someone can be jailed for "slandering" the monarch. Having grown up in the United States during the 60s and 70s, Queen Noor likes to describe herself as a veteran of the civil rights movement. But no matter how hard I try to get her to explain her personal rationale for becoming a queen, she continuously deflects the conversation into the kind of the-natives-weren't-ready-for-democracy colonialist apologia perfected by the British in Africa.

Amazingly, given the transformation she has wrought upon herself since becoming queen, Noor insists that she hasn't changed a bit. "I'm the same person I've always been," she protests with an utterly straight face.

Even to a casual observer, this is manifestly untrue. "She is unrecognizable to someone who knew her in her previous life," says one American woman who met Lisa Halaby as a college student, when she took a leave from Princeton to ski at Aspen. "Some people really reinvent themselves, and you have a very strong sense of that with her," says a New Yorker who has known Queen Noor over the years. The biggest change is the loss of spontaneity demanded by a public life that requires Queen Noor to think carefully about every word she says and every move she makes. The habit of deliberation has become so ingrained that it affects even her most intimate friendships.

"She's a very different person now," acknowledges Marion Freeman. "She's more formal with me. She has lived that role for so long that the role has become her, in many ways."

Queen Noor never goes anywhere alone; even when she drives herself in her Mercedes jeep she is accompanied by a caravan of armed guards. There are always watchful eyes upon her. Privacy is a scarce commodity in such a life.

The most the queen will admit is that, behind closed doors, her public posture of acquiescence did not always reflect the private reality. A mischievous sparkle lights her eyes as she tells me that once, years ago, King Hussein forgot a very important date— her birthday or their anniversary, she thinks. As he was leaving the room, still oblivious to his transgression, "I picked up something I hoped would smash and threw it at a closing door," she says, suppressing a grin.

But such lapses were rare; even with her husband, Queen Noor exerted a steely self-control.

"For both of us, it wasn't our nature to share our problems," she says. "Both of us grew up having to become very emotionally independent from a very early age, having to look after ourselves in complicated family environments.

The fact that we grew together year after year is, I think, the reason we came out of each difficult time even stronger.

I fell in love with my husband over 20 years, more and more." By the end, the queen and the king seemed to find their mirror image in each other.

"I think we would look inside and find the other one of us," she says softly.

But while Queen Noor calls the king her best friend, she didn't even let him see the whole truth.

"I told him as little as possible of anything that might disturb him," she says. "He needed me to help alleviate the crippling burdens he had to bear, not to add my feelings of frustration or hurt or not knowing what to do. I tried to be as much support to him as possible, and I tried to deal with anything that concerned me on my own."

That sounds pretty lonely. "Yes, of course it was lonely at times," Queen Noor says quietly. "It is lonely at times."

King Hussein was well aware of her self-sacrifice: the queen "endured much anxiety and many shocks, but always placed her faith in God and hid her tears behind smiles," he wrote in his last letter to Prince Hassan.

At the end of the king's life, many Jordanians finally realized how formidable his wife was. "She never let her guard down," says Ambassador Muasher, who was with the royal family at the hospital. "She would never break down and cry in front of us; she would never act in any way to suggest weakness. She kept our spirits up. She's a strong woman. I never knew how strong until now."

Years ago Najeeb Halaby said that his daughter had a hard time adjusting to her new life in Jordan, but that she had "hidden some of the difficulties of the challenge," coping with them by herself. Since she is close to her sister as well as friends who go back to her school days, I ask if she confided in them. She shrugs. "They couldn't understand," she says with a dismissive wave of her hand.

The eldest of three children whose parents' marriage had long been troubled, Lisa learned early to fend for herself emotionally. The Halabys—whom she has described as your typical "moderately dysfunctional" late-20th-century family—moved around, living in New York, in Washington when her father was head of the Federal Aviation Administration during the Kennedy years, and in California when he worked in the aerospace industry. By the time she graduated from college, the Halabys were divorcing.

"My parents struggled with the social and economic pressures of moving back and forth between public and private life, and the dislocations of moving between the East Coast and the West Coast," Queen Noor says. It doesn't sound as if any place was truly home, or left her with a feeling that she had genuine roots. "We did not grow up anywhere," she says flatly. She describes herself as a "difficult, withdrawn adolescent," adding, "I was very much of a loner. I just kind of found my own way, independently. I relied on myself as much as possible. We didn't grow up cozy-cozy. I don't know what a close family is. I only had my family, and then I've had my children, and our family isn't normal, either."

As a mother, Queen Noor has earned high praise from the Jordanian people, who appreciate the fact that she raised her children to be fluent in Arabic (unlike King Abdullah, whose British mother didn't stress that part of his education). "Her children are warm and extremely down-to-earth," says Ambassador Muasher. "They are not remote or detached from the people at all."

But the queen acknowledges that her first priority was always her husband. Last fall she told me, "We are pulled in many directions, and we're not always present, so we have to rely on the extended family for primary care for our children. We try to draw them into our lives and concerns as much as possible, so they can understand what's pulling us away, but there's no question that my primary responsibility has always had to be with my husband—by my choice, not his. In that way, I felt I was serving not only my children and their future, but our country. There are times when I wonder whether I served my children well enough in the choice I made, but only time will tell."

Now that their father is dead, she insists that the children are free to make their own choices in life—but their home is clear. "I would love it if one of my children wanted to be a doctor or an architect. My girls would like to be vets. But their lives are inextricably tied to Jordan," she says. "They see themselves as Jordanians; their future is in Jordan; they see their responsibilities as being to Jordan."

Although Hamzah is now the crown prince, King Abdullah could easily make his own son—who is four—the heir as soon as he's old enough. "People are saying that Abdullah is a transitional king, and that after a certain number of years Hamzah takes over—but there is no such thing as a transitional king," one government insider says. "The king calls the shots—period."

Would Queen Noor be disappointed if her son never became king? "I haven't even thought about it," she says. "Whatever is in the country's best interest."

The country's best interest will dictate her own course as well. "The dutiful aspect of my life, for the most part, was of my own choosing—not because of my marriage, but because of my nature," she says. "My marriage simply handed me a certain framework for duties. But the way I've gone about trying to fulfill the responsibilities I took upon myself was motivated by my own personal sense of duty, not by a queenly sense of duty. I felt all my life that those of us who had been privileged with a great education, with security and stability at home, had a responsibility to give what we could to make that possible for everyone."

She smiles wanly. "All I've been trying to do is lead a meaningful life and deserve my place on earth."

By now an evening chill has stolen into the air; the sky is darkening. As Queen Noor walks me out to my car, I tell her again how sorry I am for her loss. Her eyes unexpectedly well with tears. "I find it so much easier to comfort others than to be comforted myself," she murmurs, embarrassed.

For a moment we stand on the lawn, listening to the fountains splash and birds twitter in the tall pine trees. Surrounding us are jasmine-scented gardens and magnolias whose blossoms the queen took to lay on her husband's grave. The palace compound is lovely, but it is also an armed camp hidden behind locked gates and high walls, as circumscribed as the life of an Islamic queen.

My driver is a member of the Royal Police, so we will pass easily through the military checkpoints, each manned by olive-drab-clad soldiers, that line the road to Bab Al Salam, which means "the Door of Peace." Queen Noor will stay. The truth is that Jordan is the only home she has ever really known, and the thought of leaving it is as inconceivable to her as the thought that her life might have been otherwise.

She has no regrets. "If I had it all to do over, I wouldn't do anything differently," she says. Shivering, she turns and walks slowly back into the palace, alone.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

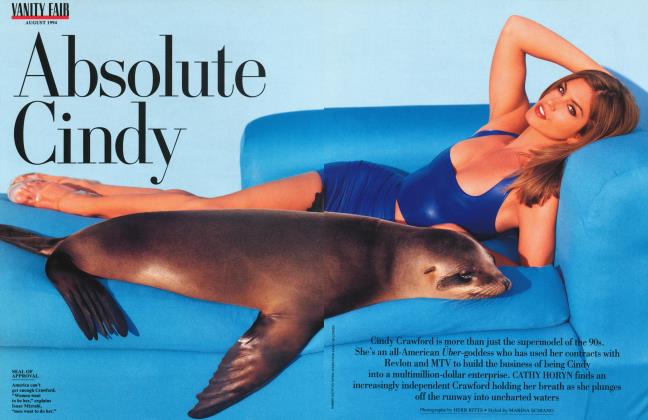

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now