Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

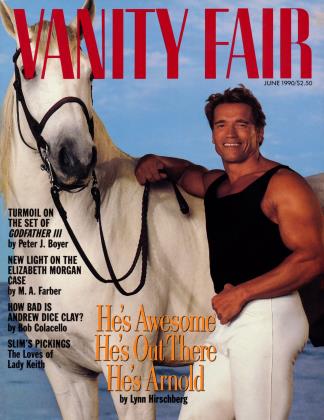

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIn Your FACE

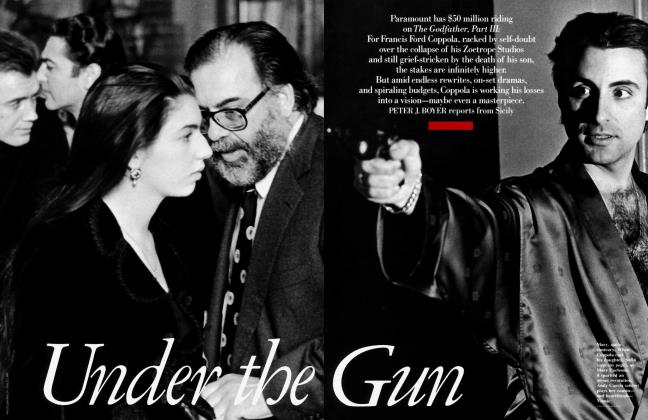

Andrew Dice Clay's X-rated, sexist, racist, homophobic humor has something to offend everyone—except Holly wood, which handed him a three-movie deal. The first, The Adventures of Ford Fairlane, rips open next month. Is the Bad Boy from Brooklyn just a mocking backlash to yuppie rule, or is he our worst nightmare? BOB COLACELLO reports from the bleachers

First there was Lenny Bruce. Then there was Richard Pryor. Now there's Andrew ' Dice Clay."

That was how the office of Sandy Gallin, one of Hollywood's reigning talent managers, beckoned ;how-biz bigwigs to the Roxy on Sunset Boulevard for "a special presentation performance" by his newest client, the controversial comic who bills himself as "the Brooklyn Bad Boy." Gallin had launched Pryor in the early sixties, so his hype had heft. "And the last time Sandy sent out invitations for an unknown was Whoopi Goldberg," says Linda Lyon, another manager at Gallin Morley Associates. "The Roxy holds four hundred. Seven or eight hundred showed up. And they were howling."

In the eighteen months since that S.R.O. send-off, Andrew Dice Clay has left a lot more people howling—not all of them with laughter. "I'm the most successful stand-up comic. Ever" is how "Dice" sums up his rapid rise. He is also the filthiest stand-up comic. Ever.

"I got my tongue up this chick's ass, right. . . you know how boring it can be when you're on line at the bank" was the opener on his hit HBO special, The Diceman Cometh, which aired on New Year's Eve 1988, and has since become a best-selling video. That same startling opener propelled him through his twenty-seven-city ''Dice Rules" tour last fall, filling 17,000-seat arenas and grossing more than $4 million—a sum unheard of for a comedy act. This February, Dice Clay became the first comic to sell out Madison Square Garden to its full capacity two nights in a row, offering 36,000 fans the cathartic thrill of chanting in unison dirty verses like ''Hickory dickory dock / Some chick was suckin' my cock.

A Jack Spratt rhyme with an oral-anal twist, ad-libbed in his intro to Cher on last year's MTV Awards, got Dice Clay banned for life from the rock cable channel. But the ensuing publicity helped push his debut LP into the top hundred, and now Def American Recordings has released The Day the Laughter Died, a double comedy album. Conspicuously absent from this new album are two longtime Dice Clay standards: gay jokes and jokes about Asian immigrants. But with X-rated riffs on everything from hunchbacks to incest, it should go gold, too.

Heavy-Metal Comedy. Outrage Comedy. The Comedy of Hate. Call it what you will, it's what sells today, and Andrew Dice Clay is not its only practitioner. Sam Kinison, Eric Bogosian, and Sandra Bernhard all get laughs off sleaze and shock. ''Take Fonzie's jacket, Stallone's attitude, and my jokes," snaps Kinison, who bills himself as ''the Outlaw of Comedy," ''put 'em in a blender, and that's Andrew Dice Clay."

Of course, it all goes back to Lenny Bruce, who was brought to trial for using the word ''cocksucker" in his routine. Bruce savaged the square oppressiveness of Eisenhowerism. Andrew Dice Clay mocks the progressive ideals Bruce and his followers fought for— sexual liberation, racial tolerance, all the sacred cows and fashionable causes of the last thirty years. He has consciously perfected the blatantly tacky anti-elitism of Roseanne, Married. . . with Children, and The Simpsons.

Dice Clay also brings to mind the nastier aspects of Don Rickies, Joan Rivers, and Rodney Dangerfield, who gave him his first national exposure— an eight-minute stint on his HBO special—nine months before the Roxy launch. A week after that triumph, Dice Clay was embraced by the cream of American comedians at the annual Big Brothers benefit, a stag night of blue humor attended by Red Buttons, Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau, and most of the studio, network, and agency chiefs. His shining moment came in the middle of his big-black-dick shtick, when he spotted Sidney Poitier sitting at Marvin Davis's ringside table. "C'mon, Sidney," he hollered, ''you know what I'm talking about. Throw it up here. Show it to 'em." Poitier guffawed, and so did the rest of the room.

"I'm just filthy. And the filthier I am, the funnier it is."

Next month, Twentieth Century Fox will release The Adventures of Ford Fairlane, a Silver Pictures production starring Dice Clay opposite Priscilla Presley. It's the first film of a three-movie deal he has with Fox. In August the studio will release The Andrew Dice Clay Concert Movie, a documentary intercut with ''home movies," written by Dice Clay himself. This summer, he's shooting the title role in The Gossip Columnist, which is being produced for Fox by Charles and Lawrence Gordon. The latter is best known for sparking Eddie Murphy's movie career with 48 Hrs.

Michael Levy, the executive producer on Ford Fairlane, thinks it will do the same for Dice Clay—make him a major movie star. He plays a ''rock 'n' roll detective" who drinks sambuca milk shakes and considers his guitar his best friend. ''If this movie makes it," says Levy, ''there's no stopping him."

For many in Hollywood, and elsewhere, that is a horrifying prospect. David Letterman won't let him on his show, and star managers Bemie Brillstein and Buddy Morra refused even to consider representing him. When Gallin signed him, his client Bob Goldthwait, a comedian whose dirty jokes target rednecks and bigots, left the agency in protest, accusing Dice Clay of fueling intolerance and ''gay-bashing," and Gallin, a generous donor to AIDS charities, of hypocrisy. Jay Leno, the Mr. Clean of contemporary comedy, telephoned HBO senior vice president Chris Albrecht after the Dice special and ''expressed outrage."

Meanwhile, Dice Clay's ex-wife, Kathy Swanson, has hired Marvin Mitchelson to slap him with a $6 million breach-of-contract suit.

And then there's the press, in which Dice Clay has appeared as everything from a Morton Downey Jr. of comedy to a neo-Nazi. Last December, The Village Voice ran the quintessential anti-Dice piece, decrying his ''Bensonhurst-style racist-homophobic-classist act" and calling him ''a demagogue playing to the random rage of the decade. ' ' By that time the self-crowned ''king of fuckin' comedy" was refusing all requests for press passes or interviews.

'Once I heard you was from Brooklyn, I said the guy's gotta have a sense of who I am." Andrew Dice Clay is sitting in the dining room of the Four Seasons Hotel in Los Angeles, explaining why he is giving me his first and only interview in almost a year. "He's cool, right?" he says about me to his boyhood friend and road manager, Hot Tub Johnny West, who nods his Aerosmith hairdo in agreement. I decide not to mention that my parents left Brooklyn—Bensonhurst to be precise—when I was eight, in part so that their children wouldn't have to deal with people like Dice Clay, or, at least, like the person he is onstage.

The night before, at the Los Angeles Forum, I had seen him live for the first time. The audience surprised me. There were guys in leather jackets, L.A. Laker jackets, and Armani jackets, gay guys, and lots of women, on dates, in groups, some covering their faces in embarrassment, others hooting as Dice taunted a young woman in the front row: "Look at that face—I bet she's got a bush that would knock my Aunt Tilly's socks off. ' ' There were a few blacks and a few more Asians, laughing along to dumb jokes like "What's a fat chink? A chunk." As far as I could see, only one kid, in a V-necked sweater and pressed white jeans, was thrusting his fist in the air and shouting "Dice!" It was hardly Nuremberg revisited, though a German word did come to mind: Kindergarten. When the naughty nursery rhymes started, I felt as if I were trapped in a day-care center run by Salvador Dali. The only time the widely varied crowd seemed to turn into a single-minded mob was when Dice lashed out at the press. "Only they can't see how funny it is," he yelled, "for 15,000 people to get together to tell dirty Mother Goose stories. You know what the press can do with their fuckin' papers? They can wipe their fuckin' assholes with their papers!" Fifteen thousand kids stood up and cheered, and I slipped my notebook into my Paul Stuart jacket.

(Continued on page 188)

(Continued from page 148)

After the finale, an Elvis impression with Dice backed up by a band of Brook-

lyn buddies, I was taken to the star's dressing room by Carl Stubner, the tour coordinator. What do I call him? I wondered. Dice? Andrew? "I call him Andrew," said Stubner. "I like Andrew better than I like Dice." I would hear various versions of that line, from various people in the star-making machinery behind Dice Clay, again and again: The guy onstage is not the same guy in real life. Dice isn't Andrew. Andrew isn't Dice.

Out of the silver-studded black leather jacket, he appeared smaller, softer, flabbier than he had onstage. Dice is cold and slick. Andrew was warm and likable. Dice barks. Andrew schmoozed. He introduced me to his girlfriend, a pretty blonde he calls Trini Benini, but whose real name is Kathleen Monica, and to his father, Fred Silverstein—Dice's real name is Andrew Clay Silverstein. "My dad does everything with me," he said. Dad was wearing a light-blue sports jacket, a beige-on-beige shirt, beige slacks, and black Gucci-style loafers. Warily, he asked me what part of Brooklyn I was from, and then said that they were from Sheepshead Bay but had made the mistake of moving to Staten Island for five years. "We moved back," he added. "I missed the candy store on the comer." He said he was in construction for years. "Until I got involved with this kid."

"Trini," said Andrew Dice Clay, collapsed on a couch, "I think I should have a turkey sandwich now." Trini went to the buffet of cold cuts wrapped in yellow cellophane and made it.

"He has to have a turkey sandwich after every show," explained movie producer Howard Rosenman. "No drinks, no drugs—just a turkey sandwich." Rosenman was just one of the phalanx of executives congratulating their rising star: Joe Roth, chairman of Fox Film Corporation; Joel Silver, Michael Levy, and Barry Josephson, all from Silver Pictures; Rick Rubin, the producer of Dice's records; Michael Rotenberg, from the Gallin agency; and Sandy Gallin himself.

"We can hang in L.A.," said Dice Clay as he escorted me to the door. "And I'll tell you how much I hate it. Then, next week, we can hang in Brooklyn, and I'll tell you how much I love it."

So now we're hanging at the Four Seasons—Andrew, Hot Tub, and me. Dice Clay has on one of his 350 black leather jackets, a black T-shirt, baggy jeans, black boots. A gargantuan silver eagle hangs from a thick silver chain around his neck. "I'm into silver," he says. "To me, gold's too showy, you know what I mean?" He tells me with startling self-confidence, "We just saw a rough cut of Ford Fairlane. It's the hit of this summer. A big hit." He also predicts that The Andrew Dice Clay Concert Movie will earn him an Oscar nomination. "I'm not sayin' I'm gonna win it. But I'll be nominated, because it's that good, and I'll be that good."

So I guess he's looking forward to Swifty Lazar's party at Spago?

"I don't even know who that is. Never heard the name. I've been to Spago once. I'm never goin' again. This is when I actually had to diet to get ready for Ford Fairlane. I was with Joel Silver, and he goes, 'I'll order for you.' And I go, 'Look, tomorrow I go into training—up till then I'll eat what I want.' And I ordered a pizza. They bring this little thing, it's not even pizza, it's like melted cheese on pita bread or something."

When his cappuccino arrives, he takes another long drag on another Marlboro 100 and informs me that he also "can't stand" the Polo Lounge or Le Dome. "If someone said, 'Meet me at Le Dome,' it's like, 'Wipe your ass with it—you go to Le Dome.' "

Is he serious? It's hard to tell. Sometimes there's a wink in his voice, other times a snarl, and he controls the switch. Perhaps he's aware that his ambiguity about the Hollywood establishment is matched by their ambiguity about him. Though they're backing his movies and records, they're slippery when it comes to backing him in print. David Geffen, whose company distributes his records, wouldn't talk. Sandy Gallin said little more than "He's the most haimisher guy I know. Nobody's nicer to his mother and father." Barry Diller, the chairman of Fox, said he doesn't find his comedy offensive, and gave most of the credit for the three-picture deal to Fox movie chairman Joe Roth, who was more forthcoming in defending Dice Clay's artistry: "He's a very good actor, and the part he plays onstage—the Diceman—is a very well-thought-through character." Joel Silver adds, "Andrew's a sweet, smart guy who found that the more outrageous he got, the more response he got."

Dice Clay lights another cigarette and says, "Let's milk this horror town good." He takes a drag. "Look, I love what I do.

I love to entertain. And I love bein' successful. But when you talk about this city, Hollywood, I just despise it. And I despise most of the people in it. ... I've been out here ten years. It's a rough town. The roughest place I've ever been, you know what I mean? It's like you just see that look: I got to make it. They don't care about anything else. There's nothin' wrong with havin' a goal. It's just a matter of how you get there. Out here, it's a lot of leeches and parasites. It's just kissasses. I was at the Comedy Store for about eight years before it started happenin'. Never once did I go over when I saw Richard Pryor or Robin Williams and look to kiss ass. Never once.

"I just bought a beautiful home here, and my parents look at each other when I go, 'I love the house, I just hate where it

is.' If the house was in Brooklyn, I'd love

it. I just can't like it here. . . . These people have no heart and soul. All they know is money. I don't need $100 million. I don't want it. And I'll make sure I don't have it, because it's all too much. They can't build houses big enough. If one guy's got three Mercedes, they gotta have five. I can't figure it out. I'm not like that."

How many cars does he have?

"I got a Lincoln Town Car and a '70 Cadillac Coupe de Ville, the original Dicemobile. And a '70 Cougar. I love old cars, but I was on the phone with my dad about a year ago and he goes, 'I wanna see you get a new car already.' I hung up, I went to Lincoln in Beverly Hills, I took this black Town Car. I come home, I said, 'I bought the car.' And they loved it, my parents. ..

"I mean, money's great to buy shit. But you don't need everything. I just want to take care of me, my family, that's it. That was always the aim."

Andrew Clay, as he called himself then, left Sheepshead Bay for Hollywood in 1980, when he was twenty-two. He'd started doing comic impressions when he was seventeen, first at a local club called Pips, then at the Comic Strip in Manhattan, until the owner got tired of letting his mother, father, sister, and assorted aunts and uncles in free. That's when his father took charge of his career, calling discos like Xenon, the Electric Circus, and Blossoms on Staten Island and, as Dice Clay tells it, "giving them the rap: 'He's Travolta, he's Rocky, he's Elvis, he's un-be-lievable!' You know, I would come on as Jerry Lewis in The Nutty Professor and end up as Travolta in Grease."

That was the act he brought to Mitzi Shore, whose Comedy Store on Sunset Boulevard and its Westwood branch were also proving grounds for Garry Shandling, Howie Mandel, Yakov Smirnoff, and Sam Kinison. "I met him in the driveway

at the Comedy Store," Shore tells me. "He said he wanted to audition, and I said, 'Good, because you're gonna be a big movie star someday.' It was his whole demeanor, the way he walked in that leather jacket. He had it. Dice wasn't in his act then, but he was Dice. He had that persona."

So he is the guy onstage?

"No!" She laughs. "I don't know anymore. It's not a Jekyll-and-Hyde transition. There might be a little bleeding in between."

Linda Lyon, who met Dice Clay about 1981, says, "He was very driven. If Mitzi had him on early at the big club, then sent him to the small one, then back to the big one for the two A.M. show, he would do it. He always put his all into it. The sex stuff hadn't started yet, but he was extremely sexy and charismatic. And the audience responded to him right away. The girls did."

According to Dice Clay, the promiscuity of women in Los Angeles amazed him. "I always had a steady girlfriend like since I was sixteen, but I'm not going to say that every chick I met in Brooklyn, I would nail her. Because I didn't. But I come out to L.A., and it's like any girl you meet, they're goin', 'Hey, why don't you come over?' I just couldn't believe it. They were filthier than the guys. I'd have guns pulled on me by chicks—I used to have this fake gun, like a starter pistol. I woke up another time handcuffed to my window. And she's laughin' like some real sicko."

It was misadventures like that, he says, that led to the birth of "the Diceman" in 1983. "I just started talkin' about things that went on, you know, the decadence out here. It wasn't a gimmick. I did it because it was on my mind. It was like, 'Do you believe last night?' It was just twistin' stuff around."

Dice Clay doesn't see why some people take offense at the Diceman's idea of the perfect woman: "Two tits, a hole, and a heartbeat."

"Look, it's like if I get hassled by someone in the crowd, I'll say, 'I don't write this material. You do.' It's that simple. I'm not talking about anything that doesn't exist. ... I think Dice is a comedic hero. You know, comics always get onstage and go, 'I can't get a date. I can't get a girlfriend. ' I come up and say, 'Hey, if I meet 'em, I bang 'em.' And that's any guy's fantasy. And it's some girls' fantasy. It's hilarious. I know I'm funny. Clean or dirty. My timin' is great. So no matter what I say, it's gonna come out funny."

Many gays, I tell him, don't find his gay jokes funny. He is at pains, he says, "to say this right."

"Before I came out to L.A., I didn't really know from gay people. And the first time I walked outta my house, I saw two guys kissin' in the street. To me this looked strange. And to me, as a comedian, it's a joke. And with my persona onstage, this would be something he would talk about. But I didn't get vicious with it. I don't really get too vicious with anything. I'm just filthy. And the filthier I am, the funnier it is. And anyway, I don't do the gay stuff anymore. I'm bored with it. I did it. I'm doing the handicapped now. It's like you go to the mall and every parkin' space says, HANDICAPPED. How many fuckin' handicapped are drivin' around the mall? And another thing, why don't they have parkin' spaces for midgets?"

By the time the sexual material took over his act, Dice Clay was going with the girl he would marry in July 1984, Kathy Swanson. "He brought her into the Westwood Comedy Store one night," recalls Linda Lyon. "She looked as pure as pure could be—long, straight blond hair, blue eyes—you know, the epitome of what you would take home to your Jewish mother and father."

To hear Dice Clay tell it, the marriage, which ended in divorce in 1986, was a disillusioning experience. "Complete horror show," he says. "Marriage scares me because of that. Because it was a girl I went with for like four years before I married her, and then, like, nine months after I married her I come home one day and she goes, 'I think I've lost feelings for you.' And I'm lookin' at her like, 'What? Why couldn't you tell me this before we got married? Now you lost them?' "

Kathy Swanson tells a different story. Bom and raised on a farm outside Fort Dodge, Iowa, she moved to L.A. in 1979, when she was twenty-two. She is currently employed as a receptionist in L.A., while trying to revive the acting career she claims she gave up to help support her husband's. In fact, she tells me, the marriage went sour when she "stood up" for herself and told him that she wanted to pursue her career. She says he exploded and told her, "Absolutely not. It's you or me. When I make it big, I'll put you in all the movies you want. What are you worried about, Doll?"

"That's what he called me, Doll. It was always Dice and Doll. Nobody at the Comedy Store even knew my real name for the longest time. And I was not allowed to tell anyone we were married. He said it would hurt his career. It's not that I'm bitter about Andy leaving me. What upsets me is the way the whole thing was handled."

According to the complaint filed by Mitchelson, Dice Clay "deceived" Swanson by persuading her to use his lawyer for the divorce. He agreed to pay her $1,000 a month in alimony for eighteen months, plus an additional $4,000 to cover debts. She is now seeking $3 million in shared property and another $3 million in punitive damages.

Dice Clay's response: "No comment. Other than it's ridiculous."

Swanson is extremely reluctant to discuss her ex-husband's offstage feelings toward women, gays, and blacks. "Let's just say he's got a very strong attitude about those kind of subjects. He definitely thinks women have their place. I didn't always agree with the humor. But when I said it, he didn't like it. He doesn't appreciate any criticism of his act. ' '

Kathy Swanson's lawsuit, and the hoopla that Marvin Mitchelson is creating around it, including an appearance on Geraldo, can only fuel the ire of those who see Andrew Dice Clay as a misogynist monster. Some women, however, don't see him that way. "He treated me as an equal," says Julie Warner, who appeared on his HBO special. "Unlike many men in this business, he wanted nothing from me other than to do well. And his girlfriend Trini is smart as a whip. He's a committed guy to a good woman."

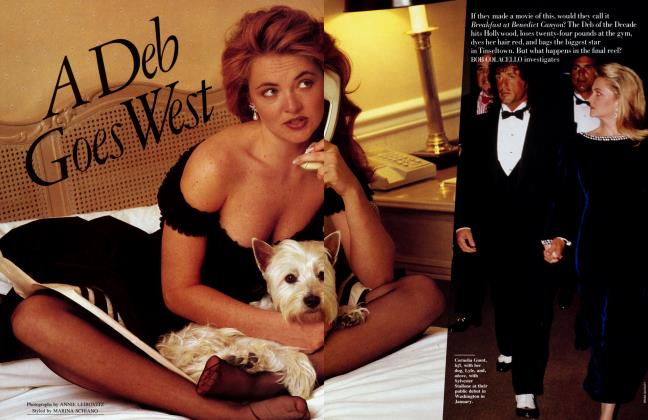

Jacqueline Stallone, mother of youknow-who, says, "There's nothing foul or crude about Dice. He loves his mother, he's a one-woman man, and success hasn't gone to his head. Sylvester asked him to come around to the house, and it was Easter, and all the rest of us are dressed up like the Easter Parade, and Andrew comes in a T-shirt and shorts. He kept saying, 'I can't believe I'm really in Stallone's house.' He couldn't function."

Back at the Four Seasons, Dice Clay is explaining how he comes up with his material. "I don't write. I do it onstage. And I don't have no writers or anything. You know, we just come up with these off-thewall lines," he says, nodding in the direction of Hot Tub Johnny West. "What was the line we came up with today? The new name for testicles? Yeah, my pit sack." He slips into his stage voice. "So anyway, I meet this chick last night and I knew she dug me, 'cause when we was dancin' slow she moved her hand between my legs and started jigglin' my pit sack." He slips out of it and adds, "It sounds funny, you know?"

He lights yet another cigarette and says, "I'm just watchin' this couple over there. She's so bored to tears it's frightening, and all he cares about is that prime rib on his plate. He's gonna get her. The music's perfect, she's failin' in love with the wine—now that's it, tank her up. Three hours from now his pit sack's bouncing off her buns."

As we leave the restaurant, four career women in Chanel suits raise their eyebrows in unison. "Don't worry," Dice Clay says, barely looking at them. "I'm with somebody."

A week or so later, we're hangin' again, this time at Andrew's threebedroom Brooklyn apartment, right around the comer from his parents' apartment and his sister's apartment, in Sheepshead Bay. The angry edge that was in his voice in Hollywood is gone. "Last year, I called my dad," Dice Clay says. "I said, 'Dad, I've got to have an apartment in Brooklyn.' I said I just wanted it clean and carpeted. I sent him a sample of the carpet from L.A."

The carpet is light gray, wall-to-wall, and the curving leather sectional sofa is light aqua, the navy blue of Brooklyn. There are only two other pieces of furniture in the living room, a very large TV with a VCR and a bookcase bursting with audioand videotapes.

We met that morning at the South Street Seaport, in lower Manhattan. Dice Clay had to pick up the Get-A-Way Chair, a computerized massage lounge, that he had ordered for his father. He was with an old Brooklyn buddy, Robert Santa, a roofer by trade, now the keyboardist in Dice's backup band. As we crossed the Brooklyn Bridge in Santa's van, Dice Clay told me that he had originally wanted to be a drummer, "the next Buddy Rich." He said that when he was fourteen he played in a trio at the Hotel Delmar in the Catskills. "The youngest person there was like seventy-seven. I called myself Andrew Silvers then. I thought it was a cool name for a drummer."

As we drove through Borough Park, the neighborhood where my grandparents lived, and which is now a battleground for Hispanics and Hasidim, I asked Dice Clay if he had been in a gang when he was growing up. "I got my ass beat a couple of times," he said. "It was good for me. It made me tougher to deal with life. I fought back. But not with a gang, just one-on-one. I don't go for the bully stuff. We used to call them T.W.'s—short for Toughie Wuffies. It was like, 'Here come the Toughie Wuffies. Big deal.' "

We stopped at M & M, a sportswear store on Kings Highway, the Main Street of what's left of middle-class Jewish Brooklyn. People recognized Dice Clay, and kids gave him the thumbs-up sign. He stocked up on his "addictions, other than gum, coffee, and cigarettes—sweatshirts, sweatpants, socks. I see socks, I go outta my mind. I'm also hooked on sunglasses, wristbands, watches—they can't make watches big enough and fast enough for me to buy." He was wearing what he called "the Dice Watch." It was black plastic and almost as big as an alarm clock.

As we headed down Coney Island Avenue toward Sheepshead Bay, I asked him if he had been good at sports as a kid. "I'm horrible. I can't dribble a basketball, and I'll be the first to admit it. Maybe that's why I turned to creative things that I found myself good at. Music. Impressions. Seven, eight years old, I was already into the drums. I watched more TV, and that's how the impressions started. Jerry Lewis, John Wayne, Louis Armstrong, the Beatles, Elvis—I used to do them from watchin' them on TV."

And now we're in his apartment, a few blocks from his old high school. "I recommend to anyone in Hollywood," he says, "who lives high up on a hill, Go back to where you come from and live like a normal person. And if you do that from when you start, you'll be O.K. when it's over. Let's say I have my ten-year run. I live high up in Beverly Hills, go out every night to posh restaurants. And then what? You do that for ten years and how are you gonna know how to walk in the mall? How are you gonna go back to normal life?"

Meanwhile, in Hollywood, the debate rages on. Is Andrew Dice Clay a dangerous symptom of the rising tide of racism and homophobia sweeping the land? Or a harmless example of the new blue-collar chic popular with the public after a decade of Dallas, Dynasty, and Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous? The David Duke of comedy? Or the nineties' Archie Bunker? A threat to Asian immigrants? Or an antidote to nouvelle piss elegance? Is Andrew really Dice? Or is Dice really Andrew? The questions linger.

Someone who has known him a long time says, "The character has totally taken over Andrew Clay. I'm not sure he even knows who Andrew is, or who Dice is."

Joel Silver disagrees. "Just like Paul Ruebens invented Pee-wee Herman, Andrew Silverstein invented Dice. Instead of a bow tie, it's a leather jacket."

"Unlike a lot of the other guys who do angry comedy, Dice's act is really an act," says Chris Albrecht, the HBO senior vice president. "He's almost a caricature, a cartoon. I don't think Dice is trying to get people to hate other people. If people were going out after Dice concerts and beating up blacks or burning down Chinese laundries, I'd be the first to object, but they're not. I think Dice is perceived as coming down on liberal values, and because of that he is perceived as being hateful. If he were making fun of conservative values, I'm not so sure that these same people who attack him wouldn't see him as a hero."

"Andrew Dice Clay doesn't bum me out," counters Bob Goldthwait. "It's his audience that bums me out. The audience isn't going to see a parody; they're going to see someone who's finally saying what they want to say. They're cheering along with the intolerance, and he's just contributing to their stupidity. I would love to believe that he was a release valve, but I find it hard to believe. Once you dehumanize women to that degree, why not slap them around? I just think there's a thin line between comedy and dictatorship these days, and he crosses it."

I called some fans at random, from a list provided by the Andrew Dice Clay Fan Club. The first one I reached was Keith Allen, twenty-two, a black customerservices man in Woodbury, New Jersey. I asked him what he thought of Dice doing black jokes. "I don't take it that seriously. I just think it's funny. I think he's making fun of the type of people who talk that way."

Joely Desjardins, twenty, a Pawtucket, Rhode Island, receptionist of Italian descent, said, "It's show biz. It's funny. I just think he's doing it for the money, and if I could do it, I would too."

"If you take him, quote unquote, seriously and you see 18,000 people cheering him," says Joe Roth, "then it's the end of Western civilization. But I think the audience sees it as a goof. ' '

And what does Andrew Dice Clay think?

"I used to actually get guilt," he says. "I used to feel guilty about the act, about everything I talk about. But then I say, Hey, you don't go out and kill people. You know what I mean? You tell jokes, whether they're dirty or not. You're makin' people laugh. And that's the bottom line."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now