Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

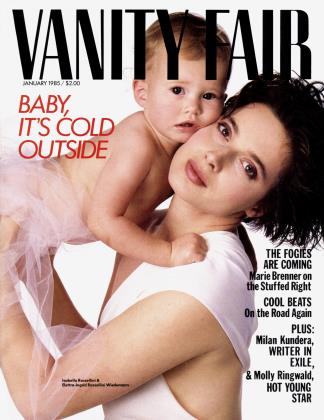

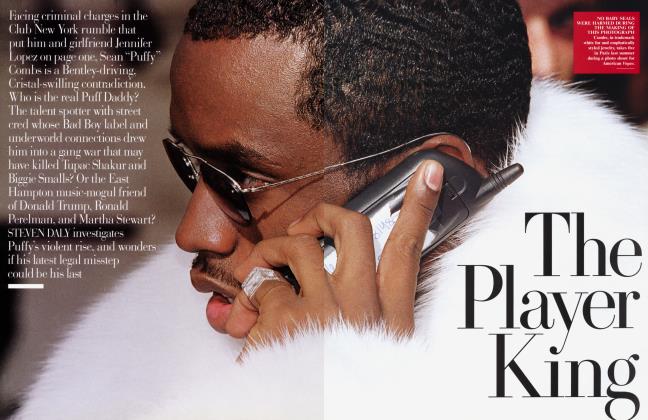

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCRICLING THE SQUARES

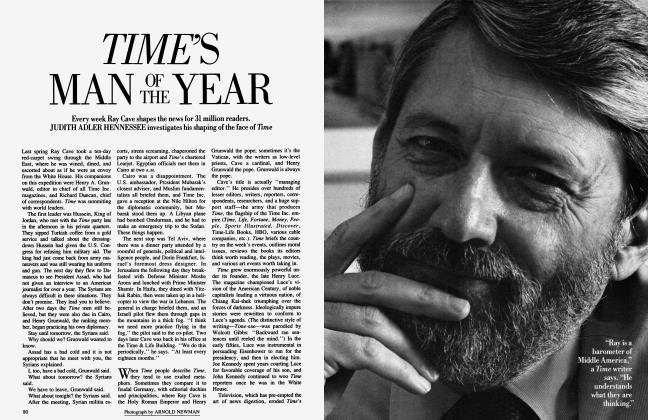

As the nation embarks on four more years with Ronald Reagan, MARIE BRENNER finds its "I Like Ike" all over again

They had come together in this splendid Georgetown house many times before on election night, to watch the returns, to share the pleasure of seeing friends vindicated and old enemies defeated, to confirm their way of life. This year, at Averell and Pamela Harriman's house on N Street, there were senators and congressmen, a former presidential candidate, a mayor who happened to be black, columnists, and Washington hostesses. The house they were gathered in seemed frozen in time, as set in its grace as the picture near the Chinese lamp in the living room of young Averell and Pamela posed on a sylvan hill, caught forever in a silver frame. In fact, these rooms had probably changed less in recent decades than the guests or their host, the former ambassador to Moscow, secretary of commerce under

THE YOUNG OLD.BOY NETWORK

"Does it bother you that we' re so conservative,and that we' re going to be running things soon?"

Truman, career diplomat and adviser, who, at ninety-two, had long since gone to bed.

Small clusters of the weary stood around the TV sets, one of which was placed near a van Gogh rendering of white gardenias, another by a Picasso study of a mother and child. The watchers seemed worn down, as weathered as the chintz on the furniture. The news coming from the screens was bad, Very bad. As the large, dread numbers rose and the terrible percentages flashed by—59%! 63%!—a barrage of television anchorspeak filled the room: "mandate," "landslide," "history-making." On Ronald Reagan's second presidential election night, the vile phrases rained into this drawing room of elite, liberal privilege. This was far more than a simple Republican victory. Among the guests, there was the profound realization of a sea change, almost as if their very way of life had been betrayed. Everything they had built their careers on—their concern for the underclass, their hatred of meritocracy and monoliths, their battles for human rights— all of it had been undone by a lousy candidate and by prosperity. Four more years! They were being told by the newsmen that out there in America all the high proles and the middles, the young, the old, and the collars of every color, wielding new credit cards and driving Buicks, had suddenly united to mow down the make-the-world-betterites.

Defeat showed on the faces of Evangeline Bruce and Clark Clifford as they moved around the room, but others at the Harrimans' searched the TV screens for lessons, for enlightenment, for any clues as to whether there would be a way back in 1988. They were rationalizing: Good, let the Republicans take the blame for the coming recession; it was all Mondale's fault. But when the results of the Hunt-Helms race, the most vicious of the Senate campaigns, came on CBS, the rationalizing stopped, and the faces in the room fell. Beside the van Gogh, Ed Muskie stood and watched the numbers coming in from North Carolina, and his features seemed to run together as it became clear that Helms, the storm trooper of the southern right, was once again confirmed. Muskie slumped in his tweed jacket and looked as aggrieved as he had the night he resigned from his own presidential run. His wife, Jane, took his arm. "I am going to get a drink," she said. "I think you could use one too."

"Come away; poverty's catching," the writer Aphra Behn instructed the English Roundheads three centuries ago. Today, in an era of extreme conservatism, Americans across the country, united by money and propriety, have come away from the elitist left. The traditional upper-class affection for the concerns of the underclass has been cast off by a middle-class revolt. Suddenly, it's hip to dress up in your Bill Blass best to go to church. Nowhere is the trend more apparent than in Texas and Alabama, as James Robison, Reagan's main-man evangelist, breaks bread with ministers at Hyatt hotels and shows off his twenty-year-old daughter, as remarkable for her innocence as Tricia Nixon when she greeted school tours on the White House lawn.

Everywhere, everyone is so correct! Fashion magazines are churning out miles of copy on The Importance of Looking Proper. Time decreed, in a cover story, that manners were back, just a few months after it had announced, defined, maybe even created, in another cover story, the "I Love America" mood. In Philadelphia, David Eisenhower, Ike's grandson, was laboring over his study of his grandfather and hoping that the book would be published in time to cash in on the national mood. In Chicago, the Marshall Field's executives were cashing in too, on such items as Steiff animals and Madame Alexander dolls, identical to those the Korean War-baby customers had bought, for onefourth the price, thirty years ago. And in New York Peter Duchin, the pianist and bandleader, was so swamped he could hardly return a call. For him the era was a return to "touch dancing." In thirty days his bands had seventy-five engagements, and Duchin himself had bookings on twentyseven of the thirty-one nights in December.

In these supply-side times, everyone is so busy. Richard Perle, the architect of the anti-arms-control cabal, scurries from the Pentagon to NATO to the White House, while Ted Forstmann, of Forstmann Little & Co. in New York, arranges another $650 million leveraged buy-out.

Such movement! The high proles are swamping the Royal Hawaiian in frequent-flier package tours, while the uppermiddles inhale the Forbes 400 issue, delighting in the news that Kyupin Philip Hwang has barely hung on to his $150 million net-worth stature.

On the campuses, ponderous young men act older than their years, dropping names and talking resumes. "Everyone is trying to think, look, and act just like the rich," one Harvard senior says. In response, the intellectuals have had to rethink, regear, nip in. Even their cartoon darling, Michael Doonesbury, faltered when he reappeared in the comics still talking sixties liberalese in 1984. Jules Feiffer's liberal dancer in the leotard has faded; now a Feiffer Babbitt speaks to the conservative eighties. "I'm a neo-have. Someday I hope to be a full have," the Feiffer man announced recently. Then his cartoon mouth turned down and he added sadly, "I don't have to identify with the have-nots anymore. In tough times like these, I don't want to be fair, I want to be safe."

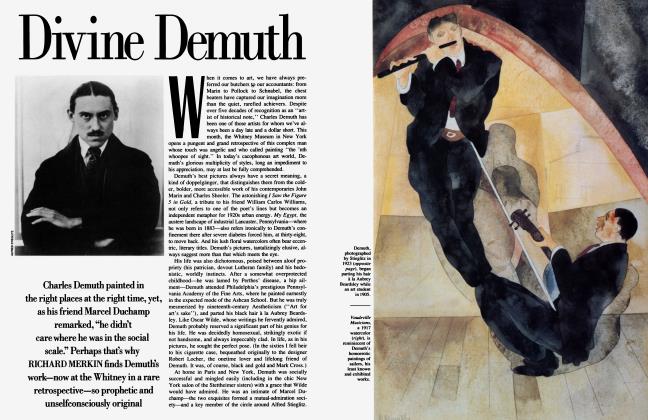

THE IKE REVISIONIST

David Eisenhower pursues his grandfather's ghost

"I think people of our era had a sense that we were experiencing things that could not be re-created, that we were experiencing things for everyone. It comes as a surprise to see that events move on and that nobody cares." The speaker is David Eisenhower, no longer the cartoon kid, the Howdy Doody of the fifties White House, or the apologist for "Nixon," as he calls his father-in-law. For a while, Eisenhower sought relief from his family's personal crisis, "that period," as he calls Watergate, by burying himself in work on the sports pages of the Philadelphia Bulletin. Now Eisenhower is thirty-six and grown-up, living a rather hermetic life outside of Philadelphia with his wife, the former Julie Nixon, and their three children. He is buried once again, this time not in baseball statistics but in historical documents, as he struggles to finish an immense history of his grandfather, the general and president.

For years David Eisenhower's name conjured up an image: a lopsided face with glasses slightly askew, as if he had just fled from a bully. He was the adolescent ambassador of Republicanism in a leftist era, the cum laude Exeter graduate who managed to get out of that institution without the slightest touch of East Coast liberalism infecting him. Then, marooned at Amherst at the height of Vietnam, he joined the navy and enhanced his stature in the conservative diplomatic service by marrying Julie Nixon. His contributions to the oped page of the New York Times further added to his reputation as the Hobbes of the young right.

"Student revolution will be doomed by the radicals' tendency to seek self-gratification,'' he once wrote, and he proved to be right. Relief, which first came in a trickle, is now a flood, and the revisionist tide has carried David Eisenhower along with it. He is no longer Four-Eyes, the outsider. He is now taken seriously, and his first volume of Eisenhower history, which covers 1944—45, will be published by Random House this year.

"Of course the revision of Eisenhower is connected to the political wave,'' David Eisenhower says. His grandfather's first term began when the country was prosperous and optimistic, just as it is today. Time magazine, in the January 1954 issue covering his second State of the Union address, described America as being "frisky as a colt." Who can resist making parallels between then and now? David Eisenhower can't, and the logic shimmers: Ike to Reagan, Reagan to Ike, an interpretive historian's dream. He says the comparison can be in the form of "a straight line or a circle," with history doubling back on itself like a bit of applied physics, a Mobius strip. But this Mobius strip is one of style: unlike Reagan, Eisenhower was opposed to the "militaryindustrial complex," as he called it, and he successfully maintained a balanced budget.

"What is really going on," says David Eisenhower, "is the revision of Eisenhower revisionism." Originally, the working-class general with the Ipana smile, "the farm boy and the last of the aristocrats," as James Salter once described him, was considered the postwar savior. He was, for his grandson and the country, "a figure of great hope and competence." Walter Lippmann analyzed his popularity by saying, "But for the Twenty-second Amendment (which restricts a president to two terms), Ike could be reelected even if dead. All you need do would be to prop him up in the rear seat of a car and parade down Broadway." Then, with the second term, Eisenhower began to be thought of as the soporific duffer with a putter, snoozing away in the pink king-size bed with Mamie, dreaming perhaps about Kay Summersby, indulging occasionally in prune whips, getting up early only to tee off with Bob Hope on the White House links. The president had become an old man who had been used up by the war; as a statesman he would be a fashionable target in the coming liberal decades.

Now, everywhere, there is a new version of Ike. Stephen Ambrose's recent biography, a Bible-size tome characterizing its subject as being "everything most Americans wanted in a President," was reviewed on the front page of the New York Times book section. The Washington Post headed its review of the book "Why Ike Was Liked." In addition, a whole cluster of new studies have appeared, including Who Killed Joe McCarthy? by William Ewald, Jr., who postulates, according to Ike's grandson, that "Eisenhower in fact saved the liberals by getting rid of McCarthy for them, the theory being that only a conservative in the White House could have pulled that off."

"We've been through six presidents since Eisenhower, when we thought we had a two-term tradition," says David Eisenhower. "Kennedy was elected with a two-term expectancy, L.B.J. couldn't manage, Nixon collapsed, Ford lost, and Carter lost, and now people think about Eisenhower and say, 'Maybe there was something in his administration that we didn't see before.' "

"The more conservative the political climate, the better he'll look," said John Eisenhower, David's father and Ike's son, who served as assistant staff secretary during Eisenhower's years in the White House. John Eisenhower made that observation in Newsweek in 1982, when the revisionist trend was just beginning, and his father's reputation has since been enhanced by far more than American prosperity and the presence of another amiable duffer on Pennsylvania Avenue. As the children of the baby boom grew up in the seventies, they looked back with longing at the fifties and developed a nostalgie du Hula Hoop. Pink plastic flamingos sprouted once again on lawns; circle skirts and pins appeared in the windows of Saks. The virtues of tuna noodle casserole were extolled in chic new cookbooks, and it seemed as if Kraft macaroni and cheese had been elevated to the status of a madeleine. Frippery at first, this fifties fad also had a ripple effect. It conjured up an affectionate feeling for a conservative era and a benign general whose "stem view of the civilian world," as his grandson phrases it, imposed a kind of order and security on another long stretch of peacetime, one that carried the A-bomb as its ominous burden.

David Eisenhower has theories about presidential styles. He matured into a historian just when the pendulum was ready to swing back, fast and hard. The pendulum knocked down the idea of an elite presidential style, that style possessed by Roosevelts and Kennedys. Eisenhower's lower-middle-class background, his struggle to power, according to his grandson, "fits in with the current wave. That is the powerful element behind the Reagan administration as well."

It is early afternoon, and David Eisenhower is strolling through the campus of the University of Pennsylvania, where he works as a poli-sci lecturer while he researches and writes. The young are all around him on the campus, scurrying into the Wharton School, ambition in their eyes. Eisenhower has been remembering the arc of a baseball as it hurtled through the Washington sky, the sound it made as it dropped into his grandfather's mitt. He also remembers a funny note he stuck in his Grandma Mamie's bathroom mirror: "I shall return." Metaphorically, he was right, but he doesn't dwell on that. Instead, he moves on to other memories and recalls that his grandfather imposed order and a this campus reaching but for standards, harmony, order. Here is another Mobius strip, the young looking to the old, the old looking back to the past, back to lawns and easy catches, wondering what's coming next. Eisenhower had a grandfather to guide him, and the country had a president, and today the young are looking once again to balance sheets and bottom lines. With the right amount of distance and understanding separating him from his youth, the historian can look around him and say, "I think the young just want to learn the rules."

THE GOD SQUAD

James Robison faith-heals the mute and counsels the president

"The sinners in Zion are terrified! God is not playing games anymore! The Carnegie Christians are shaking in their pulpits!" James Robison, Ronald Reagan's evangelist of the hour, frequent White House visitor, and star of the Praise the Lord network, was preaching to 125 Baptist pastors at a prayer lunch held this fall in the Aegean Ballroom of the Birmingham Hyatt. Not a chair in the room was empty, and as the black waitresses scrambled to whisk away the remains of the turkey Marco Polo combos, Robison went on at full tilt, hitting all his usual themes— lust, ego, demonic oppression, secular humanism, the Pha isees—and indicting everyone who placed ideas above religion. The pastors were responding nicely, hallelujahing to beat the band, while Robison's lieutenants, as manicured as est trainers, slouched against the walls, seemingly inured to the evangelist's vibrato, the spectacle, the noise. Clearly, for them, this was just one more show, one more town, God business.

God business is very good at Robison, Inc. Ever since Brother James, as he is called, was rescued from the snakeoil fringes of fundamentalism, toned down, and anointed with the invocation duties at the 1984 Republican convention, the crusade department of his suburban-Fort Worth headquarters has been busy booking him well into 1986. Even the waitresses at the Hyatt had picked up the excitement of being in the same room with James Robison. As they scurried about, refilling pitchers of iced tea, Robison decried "the Judaizers who had beaten Paul's body."

They tried not to make too much noise when Robison got to the great story of Bob, the grocery-store package boy who had been "mute, couldn't say a word," until he met Brother James in a parking lot. Robison has antagonized many a moderate Baptist by his heals-and-cures approach to religion, but not this group, who sat transfixed as he described how he had laid "a gentle hand" on the boy's neck. Nobody seemed startled by this image, even though Robison is an unwieldy size, rather like Elvis Presley on the decline, and his hand looks about as gentle as a frozen capon. "Rebuke the stuttering and the stammering tone! Go away, Satan! I rebuke thee!" Robison had screamed at the mute in the parking lot, while his wife prayed in the car. "Thank you, Brother James," the healed boy had uttered as the Robisons pulled out and cruised off, according to Robison, "in the awe of God's glory."

"If God made you sick, it is a sin to go to a doctor," Robison told the Birmingham pastors. Then he invited them to come forward, "to rebuke Satan and denounce ego," to feel his gentle touch on their neck. A good third of the room stampeded for the lectern, all those white pastors in leisure suits, teary-eyed, almost knocking down the waitresses in their haste to get near the man who, as they say, "has been given the prophetic word."

Besides the prophetic word, God bestowed upon James Robison a birth that was "the product of a forced relationship," a childhood in which he committed a near-homicide when he went after his alcoholic father, and then rescue in the form of a foster father, a Southern Baptist pastor who "showed him the way." The way turned out to be an evangelical career that was forged out of equal parts of carnal charisma and Jew-baiting rhetoric. He once described antiSemites, for example, as "those who hate Jews more than they are supposed to," and he has defined non-Christians as people who are "unable to understand spiritual things."

These unique turns of phrase have not made Robison a pariah—far from it. They have brought him to semi-canonization, to electronic fame. In this new conservative era, James Robison, forty-one years old, up from the mud flats of Texas, has an immense TV ministry, a monthly magazine called Life's Answer with a circulation of 170,000, production deals for documentaries, and a guiding spirit in Jerry Falwell. He is sought out constantly for his political opinions and especially for snippets from his conversations with his friend Ronald Reagan. "The Lord brought us together," Robison says in speaking about the president.

i AM THE WAY! bannered Life magazine twenty-seven years ago, in the first week of July 1957. On the cover was a young evangelist named Billy Graham. The occasion was Graham's first New York crusade; he had preached for thirty-seven days at Madison Square Garden, and in that time 21,000 people had responded. Life found those numbers disappointing, but then, in the second term of the Eisenhower presidency the country was fairly benign. There was a certain degree of worry about the Communists making inroads into China, but Chiang Kai-shek himself, in the same issue of Life, revealed his plan to "roll back Reds." The teamsters had been acting up, Life reported, and a young Washington lawyer named Robert Kennedy was making his reputation as the chief counsel of the Senate's select committee to investigate the unions; his brother the senator was on the same committee.

The drumbeat of history. How simple it all was in 1957! Young Billy Graham's intent in New York that summer was so basic, so innocent: he wanted to instill in people "a decision for Christ." He wanted his followers to forsake tight sweaters, lipstick, and the telling of dirty jokes, and to feel the "instantaneous supernatural rebirth during which the Holy Spirit comes to live in your heart." In other words, to become Christians. He was asking every individual to make a personal decision; he had no collective notion like James Robison's vision of "Christianizing America." In October 1984, The New Republic detailed the method used by the new religious right to register Republican voters. Hordes of Christian soldiers had rallied around the issues of abortion and school prayer, and the right wing had seized control of the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest Protestant sect, with a membership list of over 14 million. From Graham's 21,000 to Robison and Co.'s 14 million! "State by state... movement evangelicals are succeeding in taking over local Republican organizations," Sidney Blumenthal reported in The New Republic. "The Republican Party is a tool," said Gary Jarmin, the legislative director of the evangelical New Right group Christian Voice.

THE GOD SQUAD

THE PEPPER SHAKER

"The national consciousness has got to start thinking that wealth is good. " —Ted Forstmann, financier

THE IKE REVISIONIST

"Now people think about Eisenhower and say, \Maybe there was something in his administration that we didn't see before.'"

—David Eisenhower, historian

"You have to learn to go home andlooooveyour wife. Every night."

—James Robison, evangelist

THE DARK PRINCE

"The question is, how do you avoid a war that everyone agrees would be an unimaginable catastrophef"

—Richard Perle, assistant secretary of defense

In American tides of social fashion, certain people get their moment, and this is clearly the moment for James Robison. The religious delegation of the new conservative era has been able to capitalize on the country's growing dissatisfaction with what is now seen as that crazed, self-indulgent, hog-wild "liberal" society of the Vietnam era—as remote today as the innocent world depicted in the summer of '57 in Life. The buzzwords are vague and general—"rugged individualism," "the flag," "I love America"—and for the religious New Rightniks, it is a quick hop from loving America and the flag to taking up the cross. Unlike Billy Graham, James Robison and his colleagues Jerry Falwell and the Reverend W. A. Criswell, pastor of the enormous First Baptist Church of Dallas, do not distinguish between religion and politics, religion and government, or religion and education. Nor, it would seem, do their millions of adherents.

So it is no wonder that the prayer lunch in Birmingham was packed, and that James Robison could feel quite comfortable saying, "I endorse no candidates; I just want everyone to get out and vote." Like the candidate he didn't need to endorse, Robison has an adoring wife who is a kind of semipermanent appendage. Betty Robison is a petite woman with a face that seems forever cocked toward her husband, rather like a Madonna in a van Eyck triptych. The adoration pose is accentuated by the fact that her hands never stray far from a well-worn Bible. Without that Bible, she could be any well-dressed clubwoman in this country, except for her feet, which are shod in tiny, tiny mules with stiletto Lucite heels and a spray of silvery glitter—the perfect footwear for a woman who doesn't walk very far on her own.

Betty and James married when they were teenagers, and when Robison talks about sex, as he frequently does, Betty is right by his side to confirm his teachings. He rests his ample hand on her trim thigh and says softly, "You have to learn to go home and loooove your wife." His hand moves almost imperceptibly, and then, as if that were too subtle for the crowd, it moves a bit more as he adds, "Every night." In response, Betty blushes becomingly and covers James's hand with her own.

A principal theme of the Robison campaign is education. Robison will accept nothing less than a revamping of the entire American education system. "The best education is private rather than public," he says, by which he means that he wants no more equal opportunities and government schools. In Robison's view, schools should teach that God is the center of life. For history and (Continued on page 100) (Continued from page 40) science education, he says that one need look no further than Noah Webster, who received his dicta straight from God. Robison adds, "A man who doesn't believe in God is not going to get excited about any of this, because he is not going to want to send his children to a school where this is taught."

Circling the Squares

It would be easy enough to dismiss these Robisonian visions as the futile rantings of a latter-day Boer, a man who could attract only the uneducated invisibles from out-theresville. It would be easy, but it would be wrong. Robison's followers cut across the social strata. Just around the corner in the Hyatt lobby, for example, an attractive woman in her mid-thirties named Karla Lett couldn't wait to meet her idol. She and her husband used to run a talent agency in Los Angeles, but they tired of the spiritual desert on the Coast and returned home. Now she owns an elegant shop in the Hyatt, a business she would not have been able to start, she said, ''without all the help I got from watching James Robison on the Praise the Lord network. I can't tell you what his teachings have meant to me." Even though Brother James, on his way to the prayer lunch, brushed right past her when she tried to introduce herself, Karla Lett was still intrigued by him. ''He treated me like dirt. Sometimes I think this whole religious business is just that, a business," she said, but she was nevertheless determined to be at the Robison crusade that night.

James Robison sat in the front seat of his car, hurtling through the Birmingham twilight to the fairgrounds, nervously switching rock stations on the radio. His daughter, Rhonda, the twenty-year-old Princess Caroline of the evangelical set, sat with her mother in the backseat. She said, ''I help Daddy any way I can," which means that during crusade time she greets the cripples and the mutes, ministering to them with an imperial smile that is like an indictment. Robison told the story of Rhonda's ''terrible affliction with asthma," from which she suffered for a good decade until Robison decided that it was time for her to be cured and to rebuke Satan. ''She couldn't run, she could hardly walk," he said, and his strapping

daughter in the backseat nodded in agreement.

As the car moved through the deserted fairgrounds, where a silent Ferris wheel rose like an eerie skeleton, Robison instructed his aide-de-camp about the evening's gate receipts. ''How's the crowd?" he asked. ''A typical Monday night," the prayer-and-worship leader answered; ''slow." No matter. By the time the cameras moved in for his weekly TV broadcast, the few thousand gathered had been rearranged to look like a solid block. ''You'll be doing the Lord's work if we can show America there are no empty seats," one of Robison's men told them.

Then the crusade began, and the worshipers waited for the moment when a cripple might hurl his crutches in the air. Brother James, with the chorus and Betty and Rhonda behind him, was perhaps thinking about his next date with Ronald Reagan and his plans to tell him about his coming crusade. "I am praying that the Lord is going to show me a way to go to the campuses and start preaching to the students," Robison says. "The whole world is sick of being manipulated by the humanists, and the students I see are now in the new mood." Robison is planning incursions into Harvard, M.I.T., and Boston University. "Students who are already there have told me that the students will come by the thousands," he says. "We are just going to go and communicate love to them."

THE YOUNG OLD-BOY NETWORK

The mood on campus is unenlightened self-interest

The tasseled loafer was hitting the Regency tea table with the steady ferocity of a metronome. The foot tapper, a bored, somewhat sullen young man, resented having to be in black tie for the dance going on downstairs. "As the outgoing president of the fraternity, I don't have to," he explained. It was Saturday night at St. Anthony Hall at Columbia University, and Arthur Altschul, the outgoing president, was sitting with a handsome junior named John Tonelli, the new president of the house, talking about the press. "Traditionally everyone writes about us as if we were the Century Association," said

Altschul, whose father and grandfather were discreet, proper figures on Wall Street. "My grandfather wouldn't even see the press," he continued, his voice swelling with pride. He seemed oblivious to the fact that it was close to midnight, and that downstairs girls in net dresses, clutching tumblers of vodka, were waiting patiently in the dim light for the presidents to join the fun.

Oh, the psychological comfort of a membership in St. A.'s! Described as a private club and definitely not a fraternity by one member, St. A.'s is so traditional, so familiar, it seems eternal— Gothic panels, dank stairwells, bottlegreen walls, dust balls, sign-in books, and mystery stews for dinner.

Members at Columbia take immense pride in the organization, with its history of preppy elitism, its four Ivy League chapters, and a house which physically predates the campus. St. A.'s has modernized, of course: the club rolls are now dotted with public-school boys, blacks, and Jews. But the snobbish pleasure of being a St. A.'s boy remains as keen as ever. It is even enhanced by the knowledge that their brand of fogy ism has become the national fashion. "You have connections for life," a member explained. St. A.'s boys are concerned with making the right move, being on the career track, functioning like adults. Even their role models are telling. Ask whom they admire most in society and they are likely to name Felix Rohatyn, the banker who turned the New York fiscal crisis around.

There is a terrific amount of smugness at St. Anthony Hall. Youth is inevitably smug, of course, but usually out of a belief in its own values as opposed to those of its elders, not the other way around. This is different. Here, imperiousness abounds. There is also an epater la haute bourgeoisie factor, as if these young fogies were already forty and bored with black tie. They seem so assured of themselves that they speak in shorthand about their future, as if they were already there. "We are hardly elitists," declared Arthur Altschul. "Lots of us choose not to go into investment banking. There are lots of us who take jobs at Sotheby's or Christie's."

St. A.'s boys would consider this attitude realistic, not pompous. They would say they are quite simply futureoriented, too savvy to be idealistic or iconoclastic. And in that they seem macrocosmic, no more studied in their ambitions than all the other young fogies of the current era, but very different from their predecessors of the sixties and seventies. Their conversations are filled with the material and the specific, and they are attractive to adults because they so resemble them. If their predecessors were full of cavils and questions—all those Yippie accusations!— the new young fogies are the reverse: they are full of answers, and seemingly without any questions at all.

Circling the Squares

Fitzgerald defined a generation as "that reaction against the fathers which seems to occur about three times in a century." Clearly, this is not a time of reaction. Now, though there may be a "gender gap" in the culture, at least there is no longer a generation gap. The margin of disagreement between old and young has closed. You could see that last fall in the election polls. Students everywhere took pride in their conservatism, and the trends they represented were not just political. Drugs have become a nonissue, and Peter Duchin is booked regularly for college proms. "They all want to dance to the same kind of music their parents like," Duchin says.

The statistics and the headlines in the papers all confirm the trend. The Christian Science Monitor reported that nearly thirty conservative newspapers were started on colleges between 1981 and 1983. COLLEGE STUDENTS HECKLE MONDALE, declared the New York Times in September. The Times also ran a study of the massive enrollment in theology classes, another "antihumanist" barometer, as James Robison would say; and this trend should enable Brother James to rack up the frequent-flier miles in his forays into the Ivy League.

Implicit in the blizzard of words on the subject is a tacit incredulity, as if the reporters had discovered a tribe of youths as strange as African Bushmen. Presumably, this is explainable by the average age of men in the city rooms, roughly in their thirties and forties, or a good half a generation removed from college age. Perhaps these reporters get wistful for their own don't-trust-anyone-over-thirty days as they turn their eyes campusward and wonder at the startling events that have come to pass: Students crossing picket lines at Yale!

Students who are apathetic about the nuclear freeze! Students who vote three to two for Reagan in the polls! The reporters seem dismayed that their values are no longer emblematic. Like the Harriman crowd, they feel betrayed. And this bunker attitude is not restricted to stories in the daily papers. A recent piece in Esquire, called "The Thrill of Owning," read as if the concept of capitalism had never before occurred to the writer.

"Does it bother you that we're so conservative, and that we're going to be running things soon?" asked Eric Zucker, a member of the class of '85. Fifteen years ago the question would have seemed loaded and open to various interpretations, but there was no hidden meaning in Zucker's tone. He was eating dinner with his friend Ralph Taddeo, who was equally self-assured. "People our age have become extremely self-oriented," he said. "We are getting back to rugged individualism. Anyone in this society who is not making it is choosing not to."

"Rugged individualism" St. A.'sstyle precludes a concern for society at large. The young fogies are not turning their backs on social issues, they are unaware of them. They are dispassionate. Naturally they cannot filter out what they cannot see. If you bring up the specter of nuclear war, St. A.'s boys change the subject. "Has anyone been killed since Hiroshima?" asked Morgan Laughlin. Most of them didn't even tune in to the presidential debates last fall.

Apathy is not the right word for this phenomenon. Perhaps it is unenlightened self-interest, carried to the nth degree. Perhaps these students are baby Howard Roarks all over again. They are different from their fifties forebears, who were "silent" as a generation. They aren't silent; rather, they are laissez-faire. How about those liberals at Brown University, you ask them, who wanted the health center to stock cyanide tablets in response to nuclear policies? Fine, say the St. A.'s guys, let the Brown people do whatever they want. Clearly, part of the young fogies' smugness comes from their lack of desire to change anyone's heart or mind.

Life is easy when you know just where you're headed. You get the right job and the gold American Express card; you manage to pay $1,500 a month in rent. Then you meet the right girl to share a dual-career life with, and

you take off on a wedding trip to some place where your parents would feel right at home, an idyllic spot, say, like Caneel Bay, the Rockefeller resort on St. John in the Virgin Islands.

There, recently, on a sailboat, was a honeymooning couple in their late twenties, a pair of grown-up young fogies named Rick and Chris. They had met through business. Chris, a lawyer, had been restless in her job, and a friend had told her to call this guy Rick, who was "good at networking." As they sailed along on the azure Caribbean, they chatted about interest-rate swaps. Chris had recently switched from law to banking, and Rick was proud of her. "She took a three-hour exam the week before we got married," he said. "We deserved this trip," said Chris, and her teeth peeked through a slash of a mouth in a determined jaw.

The presidential campaign was in progress, and their talk turned momentarily to politics, but they soon moved on to other topics. Staring over the side of the boat, Rick said he was "counting the days left" on this last fling before "life really starts and we have to go back to work." For a moment he considered the mood on campuses, how it was changing; then he dismissed that topic too. "What difference does it make what these kids are like?" he asked. "It doesn't affect my life the least little bit."

THE PEPPER SHAKER

Ted Forstmann thought big and bought up Dr Pepper

It used to be so easy to understand how rich rich was, who "we" were and who "they" were, but in the new conservative era nothing is simple, no standard measures apply. For years rich meant $5 million. You didn't talk about it if you had it; you trusted in old-money standards, good pearls and a few stones, and a decent tailor. To behave otherwise meant you were from Texas. Now $5 million will get you, in New York anyway, a rather grand apartment at 720 Park Avenue. If you invest it, you become mere hoi polloi, upper-middleclass. In the innocent, pre-OPEC days, rich was the Gettys, the Mellons, the Rockefellers, checking in with over $150 million net-net. Rich was a mink stole in the fifties, a Blackglama coat in the sixties, a few Monets and maybe a private jet in the seventies; now it's all those things and a private satellite dish at your own private game preserve on your spread near Kerrville, Texas.

Circling the Squares

An ad in the New York Times in September read: "If You Have Less Than $150 Million, You Didn't Make It." The reference was to the annual Forbes list of the four hundred richest people in America, and the point was that the bottom line had risen by a good $25 million from 1983. The tone, although ironic, was perfectly suitable to the times: "You didn't make it" was suddenly an accusation, since the goal sounded perfectly possible and within clutching distance of the country's 638,000 millionaires. New words have entered our vernacular to indicate today's rapid economic changes. Liz Smith reported that in Dallas they now say "the unit'.' to mean $100 million— as in "When I dropped six units on that oil deal, I made sure I had a unit in trust for my kids." Then there's "greenmail," a term coined by the financial press to describe the money paid by a company to fend off a hostile takeover.

The nouveau megamillionaires are hard-pressed, however, to describe their occupation as anything but investment banking or making deals. The deals can be all on paper, a matter of shuffling vast amounts of zeros in "M. and A." (mergers and acquisitions), or they can be tangible—real estate, electronics, computers, takeovers. Why specialize? The drift-down stories of our era's excesses, frequently comic, are traded by connoisseurs like rare Armenian stamps.

About a house purchase in East Hampton: "They didn't even pay a million dollars for it! It was something like eight or nine. Of course, it needed work."

About a $500-a-plate charity event to purchase some archaeological shards, at which the social ladies were out in massa, their taffeta Blass gowns rustling noisily: "Fifteen hundred dollars for something that's two thousand years old? Why, I can't even get a blouse at Saint Laurent for that."

Or Ivana Trump holding forth at lunch on decorating her new limousine: "What do you decorate a car with? Black leather, chrome, and marble. Why marble? For the sink and the hotand-cold-running-water bar."

A possession is now a "property"; a purchase has become an "important acquisition"; and charity has been elevated to "philanthropy." A few years back, Andrew Tobias shocked readers with a book called Getting By on $100,000 a Year, a startling bit of prophetic journalism which now seems merely quaint.

Fancy merchandising geared to the rich goes on from morning to night. Four-dollar home magazines instruct America's upward bourgeoisie on beautifying their houses, and catalogues for the wealthy offer everything from Ferris wheels to ermine comforters. The gold American Express card now has a platinum brother, which enables the bearer to get $10,000 in cash on demand. It was made available immediately to 300,000 Americans with superior credit ratings. At a benefit sponsored by Tiffany's, which had just been sold to Investcorp, an executive showed off a terrific present for the coming holiday season, a flawless, colorless diamond necklace priced at $2.9 million.

The phrase "status symbol" has become as anachronistic as the Vuitton bag. Because too many people can afford all the symbols, true status now means being "a role model" and having your $500 million deals reported in the business press. Society's role models today are the entrepreneurial billionaires. A recent description by an associate of the oilcratic Bass family of Texas—net worth $3 billion—is paradigmatic of the times: "They're the perfect capitalists. Everybody is supposed to work hard and amass as much money as he can and also be a good guy, and that's the Basses."

The rich boys from out of town love to swagger into New York's "21" and talk about their holding companies. In photographs, these men always seem to be squinting tensely. Take Irwin Jacobs and his megamillion squint; at fortythree he controls Jacobs Industries, Inc., in Minneapolis, a holding company which deals in real estate, sugar, snowmobiles, accounts receivable, and boats. Recently, Jacobs squinted in the direction of the Aegis Corporation, another holding company, but his $51.5 million was rejected.

Then there's Charles Hurwitz, a Houstonian who says he prefers the quiet life, while running MCO Holdings, Inc., which specializes in oil and gas as well as the hostile takeover. Last spring he tried a takeover of Castle & Cooke, Inc., the Hawaiian food company. He didn't get it, but his 11.8 percent stake was bought back by Castle & Cooke for $70.8 million. In Miami, Victor Posner, the troubled self-styled billionaire, sixty-six years old and a high-school dropout, bought out Royal Crown for $241 million last year. At the same time, he also offered $2.4 billion for City Investing.

The supply-side atmosphere has created a positively festive spirit among the deals people. The venture capitalists are jubilant because the tax rates on capital gains have dropped as the time period to utilize them has been shortened, so large sums have been freed for new investment. Some of the deals are absolutely Proustian in their creativity and complexity, and the New York Times business pages have become the hot read of the eighties, rich in Judith Krantz subplots as companies fight takeovers and new players emerge from the dim veil of anonymity that concealed the rich in times past. Besides Victor Posner and the Bass brothers, there are Carl Lindner, Saul Steinberg, Carl Icahn, Henry Kravis, Gordon Getty, and Sir James Goldsmith.

Of all the new permutations, none is more controversial or complicated to pull off than that most stylish of the big deals, the LBO, or leveraged buy-out. It is the deftest way of taking the control of a company out of the hands of the many, the public stockholders, and putting it into the hands of the few. This privatization of capital, in which companies, instead of going public as they did in the past, go private, is the fashion of the eighties.

"The leveraged buy-out has been done since Socrates," says Ted Forstmann of Forstmann Little & Co. "Anytime you went to anyone to borrow anything to acquire something, you could call that an LBO." He adds: "Real wealth is a property of the mind."

Ted Forstmann is the kind of man who in another era might have had the Robert Evans role in The Sun Also Rises. There's a look of the perpetual chase about him; you can see in his eyes all the models, the cars, the nights of poker, the early mornings at Le Club. Forty-four, never married, handsome, dark, and lean, Forstmann's idea of a good time is to carry on a dialectic about economics. Although he was reared in a rather grand Catholic family in Greenwich and became an All-Eastern hockey goalie, Forstmann was a misfit. He had to talk his way into Columbia Law School, then into an assistant's job on the homicide bureau, and later into a series of smallish deals. Meanwhile, his older brother had made a fortune and married Charlotte Ford. What was Forstmann to do? Like a true supply-side thinker, he began to think, and soon an idea occurred to him that was so simple, so pure, but so significant: Think Big.

Circling the Squares

That meant no more small deals. If a man wanted to acquire a company worth $300 million or more, he had to go to the people who had that kind of money to invest—the pension funds. "Everybody told me this was ridiculous," Forstmann said, "even my own brother, who managed pension-fund money. But I had a need not to be wrong. Ideas are where wealth is."

And so, in the late seventies, Forst-

mann started agitating, found the money, found the deals, spent most of his time on planes sifting through annual reports and proxies, meeting management, learning what was a bargain, and for whom, and how. He and his two partners, his brother Nick and Brian Little, have so far orchestrated nine sizable LBO's. The largest of these is their most recent acquisition, Dr Pepper, the Texas soda that vies for third after Coke and Pepsi, "the friendly pepper-upper," as it once was called. Somehow, however, the deal generated considerable unfriendliness in a phalanx of financial writers, who indicated that they would like Forstmann to fail with his $500 million debt, and Dr Pepper to go down the drain.

Forstmann is annoyed by what he considers to be unfair treatment by the press, but he agreed reluctantly to talk about Dr Pepper, with the proviso that he could also speak about what he really likes to dwell on, economics and conservative philosophy. "For years, we lost our heads about economics in this country," he said, and he spoke about "active" and "passive" riches and the notion of "creating value" rather than

just accumulating a pile of dough. Dough piling is "inactive," according to Forstmann. Investments are active. LBO's are active. Active means keeping the mind open to new theories, as Forstmann always does when he lunches with Jude Wanniski, author of The Way the World Works, or George Gilder, the neo-con Tocqueville, or when he flies down to the White House to chat with Ed Meese and Ronald Reagan. Having arrived at "active riches" through their own daring and initiative, Forstmann and his colleagues have a favorite intellectual punching bag: all those "well-meaning elitists" and demand-side monetarists like Milton Friedman and Lester Thurow, who was influenced by that Satan of Satans, John Maynard Keynes.

Keynes! The supply-siders are almost as vociferous in their hatred of his "zero-sum" ideology, as Thurow called it, as James Robison is about the secular humanists. "The national consciousness has got to start thinking that wealth is good," Forstmann said. "There is a classic case of zero-sum thinking. Let me explain. Two kids are going to the same piano teacher. One has talent, the other doesn't. The zerosum advocate says, 'Give the student who has no talent the lessons, because that's fair.' So that means not only do you not get a Horowitz by developing the one kid who might have talent, you don't get a potential lawyer or a boxer by figuring out what the other kid might be good at."

Circling the Squares

Ted Forstmann turned out to be very good at the LBO, and was finally recognized for his talent when he took the ''friendly pepper-upper" private for $650 million. ''Everyone wanted to believe we were stupid," he said. "They thought we had vastly overpaid." Forstmann Little put in $150 million, the banks $500 million. "In the year we bought it, the company had made all of ninety-three cents a share, but we saw something other people didn't see."

Assets! Dr Pepper had a smorgasbord of companies attached to it, bottling plants, real estate, properties that stretched through Dallas and Boston, and when these were sold off, the price of the company was reduced to something like $200 million, "which was a bargain," Forstmann said.

That's where his think-big philosophy came in. It's not that no one else on Wall Street had noticed Dr Pepper. For months, Lazard Freres had been offering the company around, and seventeen corporations had turned it down. "Nobody was interested," Forstmann said. "To sell off $500 million worth of assets would have required these corporations to have opened entire new departments. We wanted it more than anyone. We were willing to put in fourteen-hour days to get it."

He had just returned from a weekend in Dallas, where he had been helping his new acquisition celebrate its hundredth birthday. Now that he is management, he was a little concerned by the spectacle he had just witnessed, a Texas-style extravaganza that featured dinners for four thousand bottlers, distributors, salesmen, and friends as well as concerts by Crystal Gayle and Kenny Rogers, off-color toasts by Bob Hope, and round trips to Leningrad for the bottlers who had capped the most soda. The price for this Dr Pepper centennial weekend was $2 million. Forstmann blanched slightly. "Let's just say it had been planned before we took control of the company," he said.

But anyway, what's $2 million for a weekend? "There really is no limit to what can be made in this country," Forstmann was saying as his car and driver moved slowly up Madison Avenue. The glass of the skyscrapers sparkled mightily, and inside, American capitalism was hard at work. Forty-four floors due north in the G.M. Building, a long list of messages and appointments awaited Forstmann.

As they paused in traffic, the driver handed him a small package and said, "The picture is back from the framer, sir." Forstmann ripped open the brown wrapper and took out a photograph that was a perfect document of these supplyside times. It was a picture of Ted Forstmann, forty-four years old, gripping the hand of Ronald Reagan at the White House. Both men, young and old, were smiling, very, very widely.

THE DARK PRINCE

Richard Perle torpedoed SALT II

Richard Perle, the "Dark Prince" of the Defense Department, is under siege. Though he calls himself a mid-level official, and though on the books he is a mere assistant secretary of defense (and there are almost a dozen of these), leaks from the White House indicate that in the second term of the Reagan administration he will be the first to go. His area is international security policy, and his area of expertise is arms control. According to the New York Times, he is the leader of the "anti-arms-control cabal," and according to Strobe Talbott in Deadly Gambits, he has become so powerful that he was able to destroy

SALT II.

Just back from several weeks of soothing the Allies in NATO, he sits in an ominously silent office and waits for the phone to ring and the inevitable adversarial play to start up—Defense versus State, State versus White House, in the endless debate over arms control. One thing is always certain: The more talk of treaties with the Soviets, the more complicated life gets for Richard Perle.

Power in Washington shifts constantly. In the first Reagan administration, it was generally believed, Richard Perle came to dominate our internal armscontrol deliberations mainly because his superior, Caspar Weinberger, had not sufficiently mastered the complex issues to deal with them himself. It was left to Perle to hold the line and take the doctrinaire approach. As Perle himself said, "In arms control, there is always the danger of sliding into an agreement for its own sake, regardless of its terms and the impact of the agreement itself. ' '

A similar situation existed at the State Department, where George Shultz salaamed to the arrogant brilliance of Richard Burt, his assistant secretary of state for European affairs. The two Richards, as Burt and Perle came to be known, were friends, of sorts; in fact, Perle had recommended Burt for his job. But their philosophical differences could not be read immediately in their contrasting personal styles. Perle looked soft, but his ideology was somewhere to the right of Genghis Khan's. Burt looked so hard-edged he might have been an anchor on the news. And here was the conundrum: It was tough-looking Burt who thought soft, or softer than Richard Perle, at any rate. And it was Burt, not Perle, who was credited with wanting to start talks on arms control.

Their debate on the subject raged, but quietly, for they were both generally skeptical of any agreements, and their dispute was a matter of degree. They both had a deep distrust of the Russians and a great ability to speak like diplomats. Especially Richard Perle. He filled the air at the Pentagon with his objectives and programs, and his catchy era-defining labels like "new realism," which camouflage trillion-dollar defense budgets and make reality seem as far away as the next galaxy.

Perle believes that he has history on his side. "I don't want to make too much of this," he says, "but if you go all the way back and look at arms control, let's say back to Carthage, you will see that after all the agreements Carthage made with Rome, Carthage was destroyed anyway. ' '

As a "new realist," Perle is lucid about the models for failure, and if Carthage is too archaic, he needs only to look at the Hague in 1899, when the nation-states agreed to meet because they were trying to draft "an agreement to prohibit the dropping of projectiles from balloons because the conferees were terrified at the notion of.. .air power." His eyes sparkle with the irony of that particular history lesson. He settles back in his chair, surrounded by pictures of his four-year-old son and his country house in Provence and a number of Indian miniatures resting on easels, and smiles as if he had just inhaled a fine claret.

Circling the Squares

Perle is the son of a Hollywood textile converter, and he has the training of a scholar. He was thrown out of private school in Palos Verdes for general misbehavior, probably, he says, because he was bored. He found himself only after he enrolled in a course in international relations at the University of Southern California. From there he headed for the London School of Economics, and there his special form of ideology germinated. It was 1962. "I had no trouble defending America's role in the Cuban missile crisis," he says. Research for his doctoral degree led him to Washington, where he met Scoop Jackson, who immediately hired him as his arms adviser.

Perle knows that he is no longer anonymous in the government, and as Reagan focuses on arms control and on attempts to sit down with the Soviets, it is clear that a movement has started: Perle Must Go. ''It would make a catchy bumper sticker," he says. ''There are disputes within the policy committee in Washington," he adds, ''but the differences between Rick Burt and me are minor when compared to the differences between the two of us and the Soviets. The reason why there is no treaty is that the Soviets are not going to sign a treaty that is going to satisfy Richard Burt or me or any other official

in this administration... .The question is, how do you avoid a war that everyone agrees would be an unimaginable catastrophe? Do you believe that the way to do it is by signing agreements with the Soviets? Do you believe that the way to do it is through strength so that the Soviets are never tempted to start a conventional war that could lead to an exchange?" The questions hang there, ominous and remote, for a moment. Then Perle says, ''My own view is that we have to rely on sufficient strength to deter. ' '

''Sufficient strength" means, for Perle, an arms buildup, the development of star wars, and billions spent on testing that might provide, in his words, ''a cost-effective defense." For Perle and for his president, the endless possibility of American technology beckons. Reagan even suggested, in the last presidential debate, when he was talking about the star-war theory, that we share our breakthroughs with the Soviets.

In this era there will be no treaties for their own sake, and the rationale for that is the failure of SALT I. SALT I is to the Defense Department what Keynesian economics is to the deal-makers; it is the visible proof of where we have gone wrong, ''SALT I permitted a very sizable buildup of strategic weapons but gave the appearance of monitoring the Soviet buildup, an appearance that was unmatched by reality," says Perle. In other words, a disaster: "So far, since SALT I, the Soviets have added over eight thousand strategic nuclear warheads to their inventory. The agreement created an unduly optimistic sense that we

were, at long last, cooperating."

And so, for Perle and his sometime adversary Richard Burt, no more SALTS. The two Richards understand recent history this way: "Here, a dozen years after the U.S. was superior to the Soviets in many areas, the Soviets are now superior to the U.S.," Perle says. "A transformation of the strategic balance has taken place in a period when we have been negotiating and living by arms-control agreements."

The direct Pentagon line of Perle's telephone rings, and he picks it up. His voice becomes serious. "You need a fill? I thought we would spend some time on sea-launch cruise missiles and then move on to emerging technologies. .." Perle is talking hardware. It is business as usual at the Department of Defense.

Outside Perle's office, down the long marble Pentagon hallway, a gaggle of schoolchildren are studying a display in the General Hap Arnold corridor, in the E Ring of American military headquarters. They are pressing their noses and cheeks against a diorama of American technology. The technology they see is, so far, all in the artist's imagination, but the mural impresses them. Moving across the idealized acrylic galaxy, the cobalt-and-navy stratosphere, they see golden ornaments, like immense Erector Sets with projectiles and dangling missiles. The children recognize the artillery immediately. "Star wars!" one yells, breaking the tranquillity, and the echo from the yell reverberates down the marble halls, past the office of the chief of staff of the air force. Then the clatter of small feet resumes. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now