Sign In to Your Account

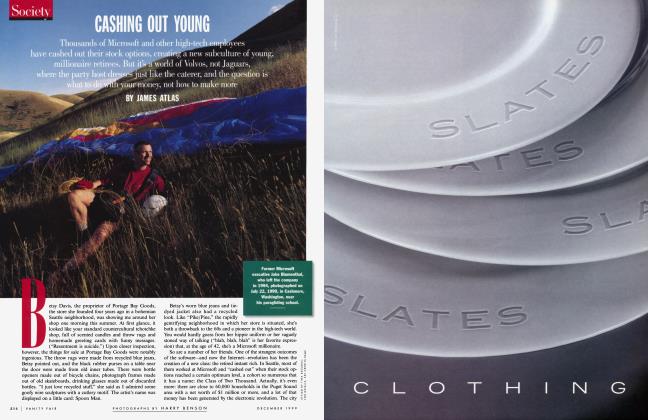

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE WOUNDED EXTILE

"Poetry comes to our aid..." It is literature that holds out the only promise of survival for Czechoslovakia as a nation, says Milan Kundera in a discussion in Paris with JAMES ATLAS

Not the curse of solitude, but the violation of solitude, is Kafka's obsession!" I came across this observation of Milan Kundera's in a British literary magazine called Granta the morning I was due at his Paris flat for lunch. Before we'd even sat down at the table, I saw why it was Kundera's own preoccupation. He was showing me around his top-floor atelier near Montparnasse, a simply furnished room with skylights in the sloping roof and contemporary artworks on the whitewashed walls, when the phone rang. It was a French journalist, with the news that the Czech poet Jaroslav Seifert had won the Nobel Prize. Within minutes, a reporter from Liberation was at the door to get down Kundera's testimony on his compatriot, Vinconnu de Prague—as the next day's headline put it. A man from Agence FrancePresse rang the bell; Kundera was "out of town," his wife, Vera, shouted over the intercom. The reporter from Liberation and I hovered around him like the two assistants who attach themselves to the surveyor K. in The Castle.

"It's always like this now," Vera Kundera complained as we sat down to lunch. (She speaks excellent English; Kundera and I spoke in French.) "We have to change the phone number every few weeks." Resident in France from 1975, when the Kunderas left Czechoslovakia for what was supposed to have been a temporary lectureship at the University of Rennes and ended as permanent exile, Kundera has been a celebrity there since the early seventies; his novel Life Is Elsewhere won the Prix Medicis in 1973. In Paris, where there are more bookshops than patisseries and the daily newspapers carry features about Corneille, Kundera's latest novel, L'Insoutenable Legerete de TEtre, was on the bestseller list for months before it was published here. An appearance on the popular television show Apostrophes last spring confirmed his status as a literary hero, Edmund White reported in The Nation: "Anyone who had watched the program with no other literary guidelines at his disposal would have come away from it convinced that Kundera is Kafka's equal and the leading author of our day."

In America, though, he's just arrived. During the seventies, he owed what reputation he had to Philip Roth, who brought out The Farewell Party and Laughable Loves, a collection of Kundera's erotic stories, in his "Writers from the Other Europe" series. It wasn't until four years ago, when John Updike praised The Book of Laughter and Forgetting in The New York Times Book Review (with an interview conducted by Roth), that he began to acquire a wide audience. The Unbearable Lightness of Being got the same treatment when it appeared last spring—a respectful front-page review from E. L. Doctorow and an interview by Jane Kramer, The New Yorker's European correspondent. Then came the Paris Review profile. Suddenly Norman Podhoretz was writing "An Open Letter to Milan Kundera" in Commentary. And this month Kundera's play Jacques and His Master has its American premiere at Robert Brustein's American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge. The director is Susan Sontag. Have I missed anyone?

Kundera claims to be less gratified than distracted by the attention. Tall and lean, with the muscular stoop of a Marlboro Man (the normally restrained French press is in the habit of describing him as "virile"), he strides about the low-ceilinged room in blue jeans, imagining what his life would have become if, as was widely rumored before the announcement, he himself had won the Nobel Prize. "The house is already like a bordello," he declares with vehemence. "I would have been vampirise, castrated, and it's a little early in my life for that. Maybe when I'm older. When he talks about Seifert, it's without a trace of envy. He describes his countryman as a poet ' 'of immense moral prestige," emphasizes Seifert's opposition to the regime, admires his reputation as un vrai play-boy: "He must have slept with everyone there was to sleep with in Prague." Seifert's Nobel wasn't "the worst choice from the point of view of the Czech authorities," Kundera says. (He doesn't need to say who would have been worse.)

It's the kind of remark that gets Kundera's heroes into trouble. Like Ludvik in his novel The Joke, who sends an ironic postcard to his girlfriend making fun of the Party and finds himself on trial for his cynical attitude, Kundera has never been very good at submitting his playful intelligence to Party discipline. Bom in Bmo in 1929, the son of a famous pianist, he joined the Party in 1947, a year before the Communists seized power. "I too danced in a ring," he confesses in the largely autobiographical Book of Laughter and Forgetting. It was a time of enthusiasm, a time when half the population—"the more dynamic, the more intelligent, the better half"—enlisted itself in behalf of the devolution. Within two years, he'd been expelled from the university for "ideological differences," only to be reinstated in 1956 and expelled again in 1970. "It was always the same," he recalls. "Some banal conflict occurs, and all of a sudden your opinions are considered undesirable; you're out of favor, then you're rehabilitated again."

Kundera came late to fiction. "I tried a lot of things: cinema, painting, music, poetry, criticism, theory, aesthetics. But none of it was serious; I think of all that now as a kind of prehistory." It wasn't until the early sixties that he wrote his first novel, The Joke, and submitted it to a Prague publishing house. In 1967, after much elaborate negotiation with the authorities, it appeared uncensored; three "incredibly large printings" sold out in a matter of days. A year later, the Russians invaded Czechoslovakia. The Joke was promptly banned, removed from libraries, "erased from the history of Czech literature." Then a professor at the Prague Institute for Advanced Cinematographic Studies (one of his students was Milos Forman), Kundera lost his job and became an "unemployable."

Silenced in his native land, he wrote for publication abroad. "Everyone was in the same boat," he recalls. "It wasn't that a few Czech writers were banned; Czech literature was banned." But Vera, who had worked in television, could no longer get a job, and eventually what money they'd saved up was gone. When the University of Rennes invited him to teach, the Czech government had no objection. "They were glad to see us go. Intellectuals were a nuisance." The Kunderas packed up their car and drove across the border, not knowing if they'd ever return. "When I left Prague I was forty-five. We arrived in France with nothing: two suitcases, a few books and records, and that was it."

Four years later, Kundera published The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, aware of the probable consequences. You don't call President Husak "the president of forgetting," the official chosen to preside over "a massacre of culture and thought," and get away with it. "It was that book that decided me. When I started to write it, I knew the book itself had settled the matter. I was never going back." Kundera's citizenship was revoked, and he was a man without a country until Mitterrand made him a French citizen in 1981.

Happy and at home in Paris, Kundera seems entirely reconciled to his fate. He and Vera have their flat, their books, their friends. Whom does he see in Paris? "Oh, writers, journalists," he says vaguely. "And of course I have—" he gestures toward Vera with an open palm—"ma femme." The rather brutal skirmishing that characterizes the marriages in Kundera's novels is nowhere in evidence. Vera, her dark hair cut girlishly short, is tender, solicitous, protective. When Kundera is overwhelmed by phone calls, she speaks soothingly to him in Czech. She worries about lunch, frets over the sauce for the ortolans and the baked apples that have come apart at the seams. Kundera praises her cooking, calls her maternelle, but she's clearly more than a writer's wife. She deals with correspondence, translates, arranges interviews. While Kundera is occupied with the carpenter who is renovating his study, she talks to journalists about Seifert. She's devoted but hardly deferential; Kundera, she jokingly confides, is a "monstre," "a character out of Dostoyevsky."

I would have said Turgenev—one of those querulous, courtly, mercurial souls with a tragic sense of life. One minute he's denouncing his translator, opening one of his novels to a page dense with corrections in his own hand, or railing against an aggressive journalist who persisted with her questions even after a telegram arrived informing him that his mother had just died. The next minute he's childlike, mischievous, gay, showing me his artwork—a papier-mache bottle, a gouache of a wild-eyed couple ("me and Vera"), a Picasso-esque sketch on a lampshade of two old men talking with their pants down.

With his pale, vigilant eyes and glowering brow, Kundera is a vigorous, attractive, yet somehow melancholy figure, the very embodiment of litost—an untranslatable Czech word defined in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting: "It designates a feeling as infinite as an open accordion, a feeling that is the synthesis of many others: grief, sympathy, remorse, and an indefinable longing." The youth whose girlfriend is a better swimmer experiences "the resentment, the special sorrow which can only be called litost. ' ' The child reprimanded by his violin teacher sinks "deeper and deeper into his bitterness, his litost." It's a spiritual condition peculiar to Czechoslovakia, a nation that has been deprived of its cultural identity by the Hapsburgs, the Nazis, and now the Russians; that has been under virtual domination for hundreds of years; that is in danger, Kundera contends, of disappearing from the face of the earth.

In such a world, literature is a serious business. It holds out the only promise of survival. "When there is no way out of our heartrending litost, then poetry comes to our aid." The revolts in Budapest, in Prague, in Warsaw, Kundera notes, were instigated by novels, poetry, theater, cinema— "that is, by culture." His essay last April in The New York Review of Books, "The Tragedy of Central Europe," provides profound meditation on the significance of literature in his native land. Czechoslovakia, Kundera argues, has nothing in common with Russia. What the so-called Prague Spring represented was a last determined stand to maintain his country's allegiance to European culture. It's not "a drama of Eastern Europe, of the Soviet bloc, of communism; it is a drama of the West."

Kundera's real affinity is with the great culture that emerged out of Central Europe in the early decades of this century—the culture of Freud and Mahler, Robert Musil and Hermann Broch. Like Conrad, who abandoned the Slavic language of his birth for English, he has never reconciled himself to being a writer from a small nation. His tradition is the tradition of Sterne's Tristram Shandy and Diderot's Jacques le Fataliste (on which his new play is modeled). "I am attached to nothing apart from the European novel, that unrecognized inheritance that comes to us from Cervantes." Kundera, then, is no dissident writer. "I'm apolitical by nature,'' he stresses. "For me, politics is a spectacle; it fascinates me, but I have no wish to become an actor. I'm not made for politics, I have a horror of politics. I like to lead a quiet life. I'm more an egoist than a militant." Podhoretz's "Open Letter" imploring him to acknowledge that his books are really about the horrors of Communism baffles him: "My early conflicts with the regime weren't ideological; they were those of an artist who didn't want to conform, who couldn't adjust to the idea of art engage, political art, that was required then. But in defending the right to live the way you want and create the kind of art you want, against your will you enter into a conflict. And when that happens, you become a political writer in the eyes of the West."

Still, to be driven from one's homeland is a devastating experience. "What separates The Joke from The Book of Laughter and Forgetting is the wound of exile," says Philip Roth. "The later work is informed by the kind of emotions that were probably somewhat alien to the exuberant farceur and defiant thinker when he was standing on native ground." The novels Kundera has written in France are more somber, more elegiac, more abstruse. They reflect the experience of living in a world where anything can happen. A "rehabilitated" Stalinist murders a nurse for no reason. A poet in the grip of patriotic fervor turns his girlfriend's brother over to the police. A group of mourners attending a funeral are distracted from their grief when someone's hat is blown into the grave. Or this scene from The Book of Laughter and Forgetting: Party leader Klement Gottwald stands on a balcony to address the people; it starts to snow, and a colleague puts his fur hat on Gottwald's head. Four years later, the colleague is charged with treason and hanged; he's airbrushed out of the photographs. All that remains of him is the cap on Gottwald's head. Even death is robbed of tragedy: "Pistol shots turn into kicks in the pants!"

Nowhere is this sense of thwartedness, of emotional diminishment, more evident than in Kundera's treatment of the relationships—if they can be called that—between men and women. The coupling in his novels is sordid, exploitative, sad. The women are embarrassed by their bodies; the men make jocular remarks about breasts and penises and getting enough ass. A reject from the Party avenges himself by raping the wife of the man who got him expelled; a repressed

school principal with a secret lust for one of the teachers in her charge offers to help him overcome his impolitic belief in God and ends up on her knees before him, reciting the Lord's Prayer—an act that revives his flagging passion. Even happily married men are forever on the prowl. Tomas, in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, finds adultery a torment, womanizing "an 'Es muss seinV—an imperative enslaving him." Martin, the uxorious husband in "The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire," collects women he could seduce, eager to sustain the illusion that "nothing has changed, that the beloved comedy of youth continues to be played, that the

labyrinth of women is endless, and that it is still his preserve." For men, sex is a deadly game; for women, another form of oppression.

"The male glance," writes Kundera, "...is commonly said to rest coldly on a woman, measuring, weighing, evaluating, selecting her—in other words, turning her into an object." Many women find his books offensive for that very reason; they reflect Kundera's male glance. "If I write a novel in which a man is mistreated, no one objects that I don't like men," he says heatedly. "If you speak ill of a man, you're told that you're a misanthrope. If you speak ill of a woman, no one says you speak ill of humanity, they say you speak ill of women. Men automatically represent humanity; women represent their sex. It's the feminists who read literature in a sexist way."

For Kundera, sex doesn't liberate us; it imprisons us, reminds us of our mortality: the unbearable lightness of being. "Everything we experience in life is so evanescent, so insignificant, so... " He finds the right word: precaire. "When it comes right down to it, what you do weighs nothing; it leaves no trace. After your death you leave no trace. It's the tragic condition of man. But in a way, it's a kind of liberation too, a relief to leave no trace. It liberates you from responsibilities; you can rejoice in your own lightness. Because if you leave a trace, you're suddenly responsible for what you are."

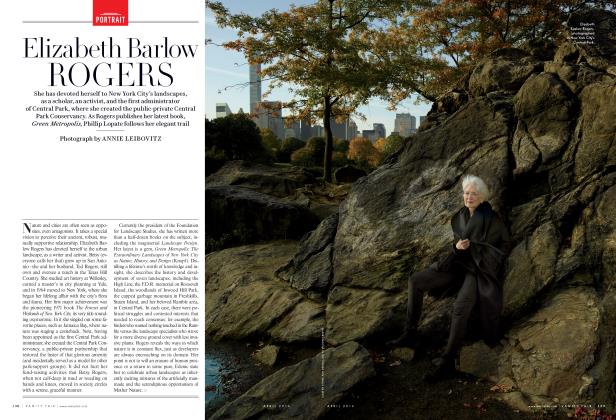

It's late afternoon by now, and the sun has come out over the rooftops. Kundera offers me some photographs, and we stand at the dining-room table leafing through his album. Kundera in a trench coat, looking like a spy; Kundera in a black turtleneck, the Parisian philosophe; Kundera in a faded work shirt, brandishing a cigar—a vrai play-boy. But his eyes in each of them are the same. They reflect sadness, anger, wisdom, vanity.. .litost.

"I'm apolitical by nature," Kundera says. "For me, politics is a spectacle; it fascinates me, but I have no wish to become an actor."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now