Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNorman

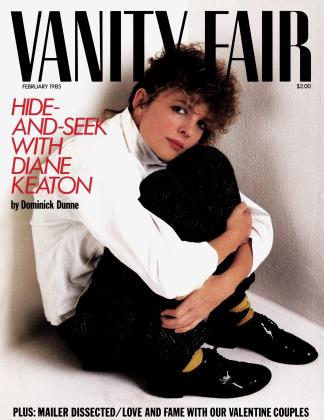

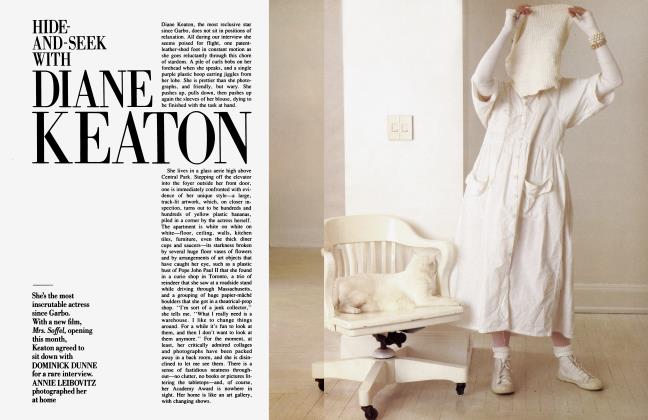

As our reigning literary tough guy, Norman Mailer has I swaggered through his own writing for years. Undaunted by the received version, PETER MANSO compiled a new portrait based on more than two hundred interviews. Excerpted here, Mailer: His Life and Times is due in May from Simon and Schuster

FANNY SCHNEIDER MAILER (mother): Norman was named Nachum Malech. Nachum is "Norman." Malech is "king" in Hebrew. We named him—he was our king. Even in the first grade his teacher recognized his talent and let him write whatever he wanted to. 1 remember her saying, "Mrs. Mailer, you have to realize that your son's pleasures in life are going to be solemn ones."

Norman shared a room with his sister, Barbara. I remember buying him a big square desk, also a chemistry set. Whenever Norman was doing something it was heart-whole; he gave everything and so his room was always a mess, but I didn't care. Bamey, his father, was very meticulous, and he would say, "Look at the mess he made." I'd say, "Leave him alone. He's going to be a great man."

MARJORIE "OSIE" RADIN (cousin): He started with model airplanes when he was about ten. He was so serious that his Aunt Anne and Uncle Dave decided he should be an aeronautical engineer, and his parents went along with it. I remember the models hanging in the living room. Anything that Norman did had to be on display.

FANNY SCHNEIDER MAILER: The snow was knee-deep that day, and Norman said, "Mother, nobody'll be here." I said, "To your Bar Mitzvah, everybody's gonna come, even the family from New Jersey." And they did. Norman gave his speech at the temple beautifully.

RHODA LAZARE WOLF (sister's closest friend): Before he went off to Harvard, Norman was usually in the back room of the apartment, studying chemistry. He'd call out, "Barbara, who's that?" She'd announce my name and he'd say, "O.K." He approved of my coming downstairs, but he didn't particularly like her other friends visiting. That he was bright 1 had no doubt. At his eighth-grade graduation the principal announced, "Norman Mailer, I.Q. of 165, the highest I.Q. we've ever had at P.S. 161."

RICHARD WEINBERG (Harvard roommate): I arrived at Harvard a couple of days early. On the bulletin board, I saw that I'd been assigned to Grays 11-12 along with one Maxwell Kaufer and one Norman Mailer. Although we were from different parts of the country, we had all gone to public schools, weren't from rich families, and we were all Jewish. It was the Harvard method that if you were Jewish your roommates were Jewish, and, as far as I was aware, Norman's social world was entirely Jewish, like that was the only thing he could relate to.

NORMAN MAILER: That summer I wrote my first half-decent story. Then in the fall, 1940, I enrolled in Robert Gorham Davis's writing class.

GEORGE WASHINGTON GOETHALS: (fellow Harvard Advocate staffer): Norman, I think, had already submitted manuscripts to The Advocate as a freshman, but he and I didn't make The Advocate until our second year, which was when we met. Even at age seventeen Norman was presenting himself as a professional writer. He would assign himself a theme, encounters on a subway with sexual overtones, say, and he'd proceed to ride the M.T.A. and watch people, then come home and write it up.

ANNOUNCEMENT IN THE SEPTEMBER 1941 ADVOCATE: Mother Advocate takes pleasure in announcing Norman Mailer won the National Short Story Contest sponsored by Story magazine last June. The story "The Greatest Thing in the World' ' appeared in the April issue of this year.

NORMAN MAILER: The prize paid $100, and I really started writing after that. My family had wanted me to be a doctor or an engineer, but with the prize they did a 180degree turn and suddenly saw me as a writer....

I once calculated I wrote a million words before I started The Naked and the Dead. Maybe not a million words, but probably three-quarters of a million, and a fair amount of this while I was still in college.

ORMONDE DE KAY (Advocate staffer): There was also another side of Norman, and it was a little bit like the figure he's come to cut over the years—the Bad Boy. He had this famous girlfriend, later his first wife, and God she was luscious. Zaftig, desirable. The impression was that Norman was sexually very precocious—it was part of his reputation—though, as far as I know, only with Bea Silverman. And Bea wasn't your proper Radcliffe girl. She was a proud woman, very much her own person and ahead of her time in terms of independence and women's rights. She played the piano seriously. Bea was definitely with Norman when I met her our junior year. They were already lovers.

MARK LINENTHAL (Advocate staffer): Bea was ebullient, gay. She would make a sexually explicit remark, and Norman would act mock-shocked but was really delighted. She was willing to make fun of it all, not in any way that was compensatory or defensive—that would somehow have spoiled the fun—and her debunking Harvard stiffness appealed to Norman, no question. One felt she was his companion in epater les bourgeois.

CLIFFORD MASKOVSKY (army buddy): There were thirteen of us that were to go to the Pacific, including Norman. We had what we call a delay en route, which means that while we didn't get a furlough we had ten days to report at Fort Ord, in California. We weren't traveling as a group— we could go out there alone. Norman said to me, ''Why don't you come into Brooklyn and we can go out to Ord together?" I did that and met his wife, Beatrice, whom I liked. Then, when we got into San Francisco, Norman said, ''Hey, we don't have to report to Ord directly. Let's be a little late." Again, his brashness, and I went along, even though by being "a little late" we were really AWOL.

It was also during our time at Fort Ord that Bea became a Wave, and I think he was angry that she'd enlisted in the navy. What he was saying was "She's an officer, dammit!" Again, his thing about officers. He had absolutely no use for them.

IS ADORE FELDMAN (army buddy): None of us knew he was a writer or that he was collecting information for a book, so The Naked and the Dead was really a bolt out of the blue. I read it in the early fifties and recognized little pieces of everybody, composites of people who'd been in our outfit.

BARBARA MAILER WASSERMAN (sister): Bea once told me that Norman wanted to go into combat so he'd be able to write the great American novel. The arrangement was that he'd be writing her long, long letters, so that even if he was killed, then at least there'd be the book.

NORMAN MAILER: When I got back to Brooklyn in '46, my neighbor was Arthur Miller. Unknown to me, Miller was writing his masterpiece while unknown to him I was slogging away at The Naked and the Dead. If anyone had told me that this tall middle-class type was writing something as powerful as Death of a Salesman, I wouldn't have believed it. Seeing him get his mail day after day, the two of us exchanging small talk, I can remember thinking, This guy's never going anywhere.

BARBARA MAILER WASSERMAN: At the end of 1946, I gave a New Year's party at Pierrepont Street. Norman was there; so was Alison Lurie, who was a classmate of mine, with William Gaddis—in other words, it was a writers' party. To all of us, of course, Norman was already a success, since he had the contract from Rinehart. The book was finished in September '47, and after turning in the manuscript he and Bea left for Paris, where he was going to study at the Sorbonne on the G.I. Bill.

MARK LINENTHAL: Harvard had been something to measure himself against; Paris was different. His mood was exhilaration when the book was about to be published. But he was infuriated by the pre-pub ads, which read: "My name is Croft. I'm one of The Naked and the Dead and you can meet me on...," giving the publication date. His feeling was that the ads were cheap, with their undercover sexual come-on, and I recall his asking me, "If you saw that ad, would you read the book?"

LONDON SUNDAY TIMES FRONT-PAGE EDITORIAL, MAY 1, 1949: ...generally their talk, reported at great length, is incredibly foul and beastly.... In our opinion, The Naked and the Dead should be withdrawn from publication immediately.

LILLIAN HELLMAN: At some point I took an option on The Naked and the Dead. It seemed to me I could make a play of it, so I used my own money, $500, which was the usual option money.... At our first meeting he was a very pleasant, interesting young man. I liked him immediately. So did Hammett, whom I had asked to read Norman's book, and he thought it was just as good as I did.

SHELLEY WINTERS: Norman then came out to Hollywood. There were two political meetings, the one at Gene Kelly's and then a big rally, also for Wallace, given by the Arts, Sciences and Professions Committee. That's where he met Marilyn Monroe. I know he says he never met her, but he's wrong.

FANNY SCHNEIDER MAILER: Barney and I went out to visit when Susie was bom. Norman was famous. They would be invited to all the top-name parties, but Bea never wanted to go. I said, "Bea, you have to go. You're Norman's wife." But Bea was the unhappiest woman in the world because all the praise was for Norman and nothing for her.

NORMAN MAILER (letter to Francis Irby Gwaltney, 1949, Hollywood): Dear Fig, .../ had a job for a while with Sam Goldwyn writing a movie for him, but Malaquais and I got fired, or that is we were going to, and so we resigned, and worse still, bought back what we had written. Now we're trying to promote it into some kind of big deal somewhere, and getting nowhere fast. Hollywood stinks.

SHELLEY WINTERS: I think he and Bea were a little intimidated by Hollywood. Like the Christmas party they gave, when they just sent out invites to everybody. Everybody wanted to meet him, so the party was chaos. Elizabeth Taylor and Monty Clift went, John Ford, Cecil B. De Mille. Burt didn't come because he knew I was going to be there with Marlon....

Norman stopped us at the door on the way out. Marlon had only talked to the waiter and Bea, not to anybody else, even though everybody wanted to meet him because he'd just done Streetcar. Norman said, "Where are you going? You didn't meet anybody." That's when Marlon said, "What the fuck are you doing here, Mailer? You're not a screenwriter. Why aren't you in Vermont, writing your next book?"

Norman began to develop those mannerisms, the accents, which he had never used with me before. He became a different person. Something was happening that was very, very, very wrong."

—Adele Morales Mailer

MICKEY KNOX: (actor and friend): Norman and Bea had spent the summer in Provincetown and in the fall gone back to Vermont, but then he started spending more time alone in New York. I was with him when he drove up to Putney to get his things.

Right after the breakup he was living in a fourth-floor walk-up, filthy halls, a horrible place... .He was desperate. 1 think he knew that Fan was going to take a long time to adjust to the divorce.

ADELE MORALES MAILER: It was a Saturday night, I had my nightgown on, was really in a good mood, and the phone rings. It's Dan Wolf. "Goddamnit," I said, "it's 1:30. What do you want?" He said, "Listen, you know I know Norman Mailer. He's a great guy, and we're here in his apartment. Why don't you come up?"

I said, "Are you crazy? I'm tired and I'm in bed. I don't want to come out."

Finally this voice comes on the phone—"This is Norman."

I said, "Oh, hi, Norman."

"Look, why don't you come up for a drink," he insisted. "Get a cab. I'll pay for it."

I started to object, but then he quoted a beautiful line from Scott Fitzgerald about adventure and getting up and going out into the night, and that did it. He was so charming that I got dressed and took the cab drive that changed my life.

FANNY SCHNEIDER MAILER: Why he picked Adele, I never could understand. She was no inspiration for anything. She didn't give him what he really needed—sympathetic understanding, encouragement, support.

BARBARA PROBST SOLOMON (novelist and journalist):

Adele was gorgeous, and of all his wives she was the most interesting. She had a fire, a sexual kind of heat.

KURT VONNEGUT: The following summer Norman and I met through Cy Rembar, his cousin. Norman would be down on the beach or walking along Commercial Street, and it was always an accidental encounter, typical Provincetown, and we'd have supper or drinks.

He was unbelievably young, as was I. He had had that extraordinary shock of becoming a world literary figure and been hanging out with Edmund Wilson and Mary McCarthy and that bunch up in Truro, the great literary tastemakers of the time, who were courting him. So sometimes he was confused, sort of feeling his way how to act. I'm just extrapolating from what it is to be human, what it's like to have that happen to you at the age of—what, twenty-five?

MICKEY KNOX: I think Norman had met Jimmy Jones in '51, and by '53 the three of us were hitting the bars on Eighth Avenue fairly regularly. Billy Styron used to join us, and one night we came out of a bar and Billy put his arms around Jim and Norman—he was really high—and he said, "Here we are, the three best young writers in America!"

ADELE MORALES MAILER: It was a terrible time. He'd finished The Deer Park, and the manuscript used to come back and Norman would get very upset. One after another, I don't know how many publishers turned it down. Norman would say, "Those motherfuckers. I'll show them."

Walter Minton was the one who finally took it, and he was very supportive. Of course, after Barbary Shore Norman knew he was on the firing line. The Naked and the Dead was a tough act to follow. The boy wonder, the money and fame—so people were waiting for him to fall on his face.

ALFRED KAZIN: I remember The Deer Park seemed to me utterly ridiculous, the idea that sex brought knowledge. Of course, I saw a connection here to Norman's bizarre flight from being a lower-middle-class Brooklyn Jew, since I've always thought the clue to the Jewish-American novel was the fact that we were the first Jews to get divorced, the first ones to have sex.

Years ago Jules Feiffer and I were talking about Norman, and someone asked, "How come these Jews get married so often?" Jules replied, "Because they can afford it."

ED FANCHER (co-founder, the Village Voice): The idea behind the Voice wasn't an original one. The existing paper, the Villager, didn't represent the cultural side of the Village at all, and at every party someone would say, "We oughta have a newspaper in the Village." Finally Dan Wolf said, ''Why don't we actually do it?"

We began to have discussions the winter of '54—'55. Dan and I were close friends—we'd met at the New School right after the war—and Dan was quite friendly with Mailer. My grandfather had left me a small amount of stock against which I could borrow, so I put in $5,000. Norman put in another $5,000. Dan didn't have any money but was a partner nonetheless.

We didn't have a polemical position, we certainly weren't Marxists, but we saw ourselves as ''the outs," as opposed to The Partisan Review, which was the Establishment. The Nation, The New Republic, and Partisan were all boring. Ideology bored us—not simply the Communist line, but the anti-Communist line too.

JERRY TALLMER (associate editor, the Village Voice, 1955-62): We were working ninety to a hundred hours a week, and my whole life was the Voice. Norman had very little to do with the process of publishing the paper in the beginning. He stayed away, basically, but he and I had had conversations the few times he came to the office before he started his column in January '56.

Each of us had his own idea about the kind of paper we wanted, including Norman, and this is where he and I had our falling-out. My concept, unlike Ed and Dan's, was to restore the "I" in criticism, in my own writing as well as other people's. Norman's idea, I think, was for the paper to be a hip shock sheet. He wanted the Voice to deal in a Daily News way with drugs, jazz, the swinging black scene, and sexuality, all under the aegis of ''anti-Establishment."

Now, among Norman's terms for writing his column was that we couldn't change a period; we were just supposed to print it as is. But he was congenitally late, and it would always be twice as long as the space allocated. We'd scream back and forth, especially me because I had to do the shit work of patching things together, forcing things in with a shoehorn at the eleventh and twelfth and twenty-fifth hours. Then I had to get into the car and drive to the printer, then proofread it, and from time to time amidst this chaos, this miasma, a typo would sneak in.

The typo that blew the thing was Norman's phrase about ''the nuances of growth" in a column on ''The Hip and the Square," April '56. This came out unbeknownst to me or anybody else as the ''nuisances of growth." We were all there and didn't catch it. We left the printers and drove back with another triumph, another issue... .We always treated the next day like a Sunday, so usually I'd be alone in the office, as I was that afternoon when the phone rang. It was Norman. He says, ''Tallmer, why don't you get your finger out of your ass."

There then followed a big scene in the back room between Ed, Dan, and Norman that night. Closed door. I think he was saying, ''It's Jerry or me," and they stood up to him... .So in his last column, Norman announced his departure from the Voice. But he also chose to write about a current production of Waiting for Godot. He began by saying, "I have not seen Waiting for Godot," then criticized it as a ''poem to impotence," announcing that he doubted he would like it since he, like Joyce, didn't believe we are doomed to impotence.

A shamefaced Norman came in a week later with a huge article which would have filled the entire paper, his second piece on Godot—he'd since read the play and seen the production and felt he'd been unfair to Beckett. But we told him we couldn't print it as a column. So he said, "What would it measure in agate?" We told him we could get it into one page. He said, "All right, I'll buy the page." Ed was so desperate for money he agreed, and Norman ran the Godot piece as a full-page ad in classified-size type, a paid ad, with a note above saying "Advertisement." Which I suppose is where he may have gotten the idea for the title Advertisements for Myself.

RHODA LAZARE WOLF: When he'd been planning The Deer Park, he'd started picking people's brains for their insights into the unconscious. He got involved with all kinds of primitivism, theories about devouring your enemy, timemachine stuff, and since he was very aware of the impression he was making, my feeling is that he deliberately brought on his own psychosis. He started getting wild with drugs, marijuana, then peyote and mescal. There was also Brubeck: he thought he was such a mensch when it came to jazz, but he was listening to the wrong thing—you don't listen to Brubeck when you want to go wild.

He was also recording his own voice with a tape recorder, and he'd have us listen, too, to analyze his accent and inflection. He'd say, "Isn't this interesting, it's coming out like a Texan..." Or "I'm doing this, I'm doing that.. .listen!" He was seeing how far he could push himself, how far he could extend the boundaries, and of course no one dared laugh at him to his face.

During the nine years with Adele, he made this tremendous change, went through all this shit, what he did to himself, other people, his parents. Those nine years were the most important years of his life, good or bad. Still, Adele couldn't have stopped him. Norman was absolutely sure his way was the correct way. He'd bully you. He was bullying everybody in those days, especially after The Deer Park and his columns in the Voice.

ADELE MORALES MAILER: Neither of us had roots, that was the problem, and I guess we thought we'd finally settle in Connecticut. The house we bought was beautiful, old, and white.

That first year I was pregnant, and I loved it. I wanted a baby, and so did Norman. He was very pleased, crazy about it, in fact. I went into New York Hospital to have Dandy on March 16, 1957, and I remember driving back up to Connecticut with her.

There were other people in the area we'd see, like John Aldridge and Bill and Rose Styron. Norman had a falling-out with Aldridge, whether about The Deer Park, though, I can't say. There was also the feud with Styron. But Rose Styron? What can I say? She's a very strange gal. I didn't like her and didn't get along with her. She was a pain in the ass.

JOHN ALDRIDGE (critic): I felt, and 1 think Norman did too, that Styron was being very, very calculating in his efforts to ingratiate himself with people who might matter to his career. He used to have weekend gatherings at his place and always managed to have people who could be counted on to help him, like Bennett Cerf. Scarcely a weekend went by that they didn't have a houseful of weekend guests, and Rose, who's the heiress to the Burgunder fortune, Burgunder department stores in Baltimore, was the perfect hostess.

LARRY ALSON (married to sister, 1950-61): It was a very bad time for Norman in general. There was great tenseness, which was observable to everyone who cared about him, and I know that Barbara tried to persuade him to see a therapist.

GEORGE PLIMPTON: I think Norman moved up to Connecticut really because of Bill Styron. They became very close. Then somebody said something, and in this case it was much worse than the episode that broke, for example, Hemingway and Fitzgerald apart. I heard there was a bitter argument in Styron's kitchen. Personal references had been made about wives.

ALLEN GINSBERG: Jack Kerouac's take on Mailer's "The White Negro" was that it was well intentioned but poisonous in the sense that it encouraged an image of violence. Mailer still saw some element of Dostoyevskian heroism in juvenile delinquents stomping an old man to death. Kerouac hated that. But myself, I didn't think Mailer was an interloper. I saw him as a knight in armor charging to the rescue. I felt there was a kinship, a sense of brotherhood.

MICHAEL McCLURE: We thought "The White Negro" was quaint, like the tail end of the hipster mentality. There was a social break between the hipster behind his shades and the post-Sartrean who's ready to act. Norman was a step beyond the hipster. The hipsters stayed behind their dark glasses, disconnected, but when Ginsberg stood up at the Six Gallery in '55 and read "Howl," that put us on the line. "Howl" was the trigger, and I'm sure Norman wrote his "Ode to Allen Ginsberg" because of that. The second part goes:

1 sometimes think That little Jew bastard That queer ugly kike Is the bravest man In America.

BARBARA PROBST SOLOMON: People like James Baldwin were saying, in effect, "Come on, Norman, you Harvard Jewish baby, you heterosexual, you ain't out in the big world of experience. We got something you ain't got—we know about crime, about being black, about being poor, about being homosexual." But Norman is also very shrewd. He knows when he's on the wrong train. It wasn't easy, to get caught short being a leftover Dreiser or Dos Passos— which is what he'd set himself up as—so when he looked over his shoulder and there was the Beat generation, he knew he had to do something to compete.

DIANA TRILLING: I met Norman at a dinner party at Lillian Heilman's in '57 or '58. I was seated at his left, and on the other side of him was Constance Askew, the wife of Kirk Askew, an art dealer. She was a big dowager-like lady with an ear trumpet—or that's the way I remember it—a bit forbidding, and I was enormously taken with Norman's behavior because he was so mannerly. He gave her his full attention. Then, when we'd got through the first half of dinner, almost as if he'd been given a signal at a Cambridge dinner party, he turned to me on his left and said, "Now, what about you, smart cunt?"

Ordinarily I'd have frozen out anyone who took that line with me. But with Norman I burst out laughing. It was such a challenging greeting, so boldly flirtatious; it was so outrageous and funny applied to me and coming right after this beautiful display of manners with Mrs. Askew. The contrast was wonderful, and we were friends at once.

IRVING HOWE: I always thought he was incredibly smart, and so did Lionel Trilling. And Diana even more so, meshuga but brilliant. The feeling we had was that we were essentially rationalistic people for better or worse, and while Mailer was crazy and sometimes dangerous—which I still believe—he was still able to get at certain things we could not. We admired it, I think even envied it. He was our genius, "our" meaning the New York intellectual group.

JULES FEIFFER: I suppose it was a special time because we were moving out of the period of Eisenhower suppression. Mailer was earlier than anybody to pick up advance notes on what was coming—he foresaw the sixties.

Why was there such an intense social life? Primarily, I think, because the people in that group, which later became known as the New York literary establishment, were all pretty much in the business of putting themselves on the map. There was always a very expensive buffet, tall, beautiful girls, East Side models, and then there'd be Mailer, Styron, Bruce Jay Friedman, Philip Roth, plus people like Bob Silvers, Jason Epstein, John Marquand, Donald Ogden Stewart, Terry Southern, as well as Doc Humes.

ADELE MORALES MAILER: In the fall we moved uptown from Perry Street to Ninety-fourth Street because Betsy had been bom the year before and we needed more space. It was when we moved that Norman began to develop those mannerisms, the accents, which he had never used with me before. He became a different person. Something was happening that was very, very, very wrong.. .but I can't talk about the thing, what happened. It's too painful.

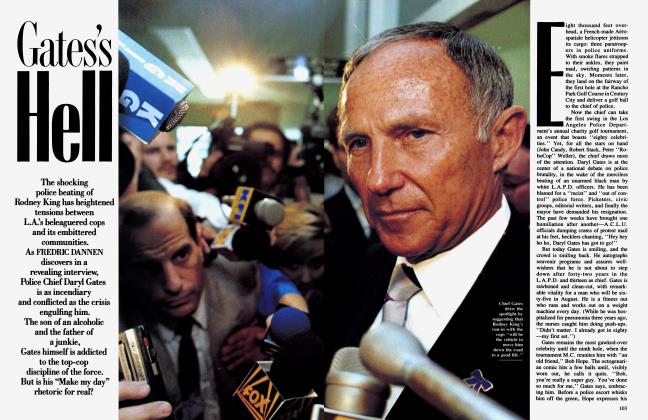

H. L. "DOC" HUMES (novelist): The party was on a Saturday night, November 19, 1960, in their apartment. The occasion was Roger Donoghue's birthday, but Norman was also testing the waters to see if he should run for mayor. There may have been two hundred people, a crazy mix including some guys off the street. I was Norman's campaign manager, and at one point in the evening I had told him, "Norman, you gotta run to lose," and he hit the ceiling.

GEORGE PLIMPTON: His campaign was based on the rather interesting idea that he was truly suited to represent the disenfranchised of the city. So my job was to get the "power structure" to his apartment so he could show its representatives off to the disenfranchised. Peter Duchin and I didn't stay very long. We went down in the elevator. Norman was out on Ninety-fourth Street. He was not in good shape at all. He was carrying a rolled-up length of newspaper, and he came up and hit me alongside the face with it. He was furious. I remember a police car across Columbus Avenue and two cops watching us, staring at the scuffling going on.

Everyone knows what happened then. He went back upstairs—the party-ground just about deserted—and in the kitchen Adele looked up, a glance at this disheveled figure, his coat tom, bleeding at the comer of his mouth, and she commented, I guess somewhat acidly, that he looked like some bum who had been rolled by a bunch of sailors in the port of Marseilles, something like that, and that was when he picked up the kitchen knife.

ROGER DONOGHUE (friend): Afterwards, what he was worried about was that if he turned himself over to a doctor who declared him nuts, then anything he'd write in the future would be questioned. He told me that the next day—"If I turn myself in it'll affect my work.''

SEYMOUR KRIM (essayist and critic): I went to the arraignment, when he made the speech to the judge: "If you put me in Bellevue it will be an indictment of my work as the work of a crazy man."

JEAN MALAQUAIS (friend and "mentor"): I read about the stabbing in the Paris papers and sent Norman a telegram to say I was standing by him. Of course, I was aware of his drinking and pills and marijuana. His purpose in smoking, he said, was to clarify his mind. He felt brilliant, he stated, capable of thoughts he didn't know he had in him. He claimed he switched from Marxism to his pataphysics of an embattled god when he started with marijuana.

LARRY ALSON: While he was in Bellevue for seventeen days, the family was gnashing their teeth. Fan always believes in him, so all she was concerned about was gaining his freedom. Barney too. Later, when Norman got out, his demeanor was that of somebody with a frontal lobotomy—flat affect, sort of disconnected.

DIANA TRILLING: Norman came to see me, and I felt very sad for him even though he didn't agree with me that he needed medical help. Anyway, I've come perhaps to agree with him that there isn't all that much useful psychiatric help to be got. What he said to me almost immediately was how awful it was always going to be, "because people will just gently move knives away so they're out of my reach." There was no question in my mind that he felt guilty for what he had done. Maybe not guilty enough, but guilty.

JUDY FEIFFER: Adele was angry, I'm not saying she wasn't, but she was a lady and her behavior towards Norman was admirable and loyal. Months after the stabbing, when life was normal again, I visited her and she told me she was going to try to make the marriage work.

HENRY GELDZAHLER (former commissioner of cultural affairs for New York City): I'd talked to Norman after the stabbing, and the following summer I was up in P-town staying at the Waterfront when he and Lady Jeanne Campbell first got together. I liked Jeanne, but I also felt she was suppressing much of her energy, subverting it to his energy. Remember, she's a Beaverbrook or Argyll.

MIDGE DECTER (writer and editor): Lady Jeanne's not an East Side lady, she's a British aristocrat, and that's a very different kettle of fish. We spent some time with them after they were married and living in Brooklyn. Her grandfather disapproved of the match, and at least at that point she was cut out of her inheritance. Mailer said, "She'll give up $10 million for me but she won't make me breakfast.'' After they split up, she said, "Here I married this terrific, powerful, dynamic, romantic literary man, and he turned out to be a guy who had to go see his mother every Friday night for dinner.''

ANNE BARRY (secretary): My diary should help get this straight, so let me see if I can find a date for Jeanne Campbell leaving. . .Aha!—"January 27, 1963: Jeannie is gone for good. She took off in an aristocratic snit."

Norman and Jeanne had been fighting. After she left he wasn't in good shape. The breakup was devastating.

ROGER DONOGHUE: I'd met Beverly in '56. A beauty. She could smile and show both rows of teeth, so they gave her one of the first big Colgate TV commercials. I used to see her every now and then at P. J. Clarke's, and that's how I came to introduce her to Norman.

At the time, he'd just separated from Lady Jeanne. We were in P. J.'s, standing at the bar, when Beverly came by with Jake LaMotta, quite high. Beverly made the crack "Well, if it isn't Norman Motherfuck Mailer!" and I guess it was love at first sight.

I don't know what happened to LaMotta that night, but a couple of years ago I ran into Norman and asked how the divorce from Beverly was going. He says, "Jesus Christ, she's gonna jump on my grave. It's goin' tough." Then we got talking about the movie Raging Bull—it had just been released—and he cracked, "Maybe I shoulda married Jake LaMotta."

WALTER MINTON {publisher, G. P. Putnam's Sons): After Advertisements he signed a contract with us for a big novel, 150,000 words or so, for a $50,000 advance. But Dick Baron at Dial offered him a contract for An American Dream for $100,000, which didn't make me very happy. I decided to step aside nonetheless.

JOAN DIDION {in the National Review): An American Dream is one more instance in which Mailer is going to laugh last, for it is a remarkable book, a novel in many ways as good as The Deer Park, and The Deer Park is in many ways a perfect novel. ...

In fact it is Fitzgerald whom Mailer most resembles. They share that instinct for the essence of things, that great social eye. It is not the eye for the brand name, not at all the eye of a Mary McCarthy or a Philip Roth; it is rather some fascination with the heart of the structure, some deep feeling for the mysteries of power.

E. L. DOCTOROW: I had lunch with Norman just before the October weekend of the Pentagon march. I was going down to Washington, too, and he said something very uncharacteristic: "1 feel I'm all washed up. I feel I'm out of it now, it's passed me by." He meant this in terms of his grasp of things, and he was really quite morose. Maybe the feeling was something as mundane as "Life has passed me by, I'm out of touch"; it could have referred to anything, perhaps his personal life, but it was the only time before or since that I'd heard him make that kind of statement. On the other hand, I know enough writers, myself included, to realize it's usually a good sign when a writer feels like that; you may have to hit bottom to find what you need.

(Continued on page 96)

(Continued from page 52)

MIDGE DECTER: Norman went to the demonstration, got himself arrested, and then, a day or two later, he called up Harper's and said, "I'd like to do a piece on it." I ran into Willie Morris's office, and the only question was whether we could raise enough money by putting together a book deal. In the meantime, Scott Meredith sold it to NAL and worked out a deal that Harper's could afford.

EDWARD DE GRAZIA (legal adviser and organizer, march on the Pentagon): After Norman's arrest, it became evident that he was going to be singled out. Everyone else was being released, sentence suspended. The deal had been worked out for everyone to plead nolo contendere, but Norman told me he wanted to plead guilty—he was refusing to take a nolo, because he wanted to say he had done it, that it was an act of civil disobedience.

JERRY RUBIN: Norman and I spent about ten to fifteen hours together back in New York. He was interviewing me, taking notes in longhand. What he was interested in was the behind-the-scenes of the demonstration, our manipulation of people.

MIDGE DECTER: Willie and I then went up to P-town to edit it, only there wasn't much editing; Mailer edits himself. He was never testy about any of our suggestions. He's an absolute pro.

The result was that the piece put Harper's squarely on the map. It was something extraordinary. An event, an editor's dream come true.

FANNY SCHNEIDER MAILER: When I heard that Norman got the Pulitzer Prize for The Armies of the Night, I said, "Umbashrien Got tsu danken," which freely translated means, "Keep the evil eye away." I had hoped he would win the prize, and then when he got two prizes, the National Book Award too, I said it again, a double Umbashrien. Still, I couldn't understand why he hadn't gotten the Nobel Prize. I figured he had a few enemies. I think he might've hurt somebody's feelings and that went against him.

IRVING HOWE: The time of the greatest tension between us was during the late sixties, when I was critical of the New Left. Norman did many foolish things, like signing appeals for S.D.S. fund-raising. He simply didn't see that there was a deeply authoritarian side to the New Left....

He wouldn't say I was wrong, but characteristically he put forward—from his point of view—a deeper, more fundamental consideration; namely, that it was not their opinions but their energy that mattered, that the S.D.S. was in the wake of history and what counted was that they'd push through.

SENATOR EUGENE MCCARTHY: In '68 there were a lot of liberals in the literary and artistic world who'd jumped in with Bobby Kennedy. Despite what some people were saying, though, I don't think Norman's politics were frivolous, his candidacy for New York mayor notwithstanding. His support of Bobby was psychological, personal with the Kennedys, and my guess is that it was Bobby's style that attracted him.

ABBIE HOFFMAN: He got up on a barrel in Grant Park and gave a little talk, then I got up and spoke, but we really didn't spend much time together, and not until later did we talk. His misgivings about the Yippies' destroying the culture were correct on an abstract level, but he wasn't talking as an organizer.

Three weeks later, I went up to Provincetown to see my first wife. I'd just finished Revolution for the Hell of It; I was kind of proud of what I'd done, and I guess I wanted to brag. I was manic. I hadn't slept in twenty days and had just been through the most apocalyptic moment of my generation—the Chicago police riots—and I was on my way to tell Norman, "I finished my book!" But a maid in uniform—a black maid, which of course was a shock—said, ''Mr. Mailer doesn't want to be disturbed when he's writing."

I'd heard the rumors about the rituals of his writing, and I shared none of it. My identity is not as a writer. I'm an organizer, so I started yelling, ''He won't see me? Well, tell him I finished my fuckin' book way ahead of his, goddamnit!" And I ran out. Later that afternoon, as I was getting on the plane for Boston, he appeared at the airport. He said, ''I'm sorry I didn't see you this morning, but I was working and I get lost in my work."

DIANA TRILLING: Norman ran for mayor, I suppose, because he wanted to make a statement about the modem consciousness. But being mayor of New York means you have to know about collecting the garbage, keeping the transportation going, getting your share of state and federal funds, learning how to allocate your money among the variety of clamoring factions, each of them representing an important vote, and, my God, none of that is a metaphor.

JOE FLAHERTY (novelist, critic, and Mailer's mayoral-campaign manager): The night of our defeat there was a party at the Plaza. Norman had rented a suite, and the two of us went into the bedroom alone. I told him, "You gave it your best shot. You were totally honest." But he still had the naive sense that we'd just missed a couple of tricks. That's the nice side of Mailer, his absolute belief in America. He never understood that unless you're some packaged shit lawyer they don't take you seriously. He was a romantic, and even as the returns were coming in he was looking for reasons.

JERRY RUBIN: In January 1970, Norman testified at the Chicago Seven trial, mainly, I think, for Abbie and me. He was on the stand maybe three hours, and described us as satirists of society, saying, "They're not criminals, they're not irrational. They're good people who believe in America and who think America's gone wrong...." Every sentence was quotable. Like The Armies of the Night, it was a statement of what the Movement was all about.

KATE MILLETT: I'd been asked to be in the Town Hall debate, in Germaine Greer's place, but I'd refused because the topic was supposed to be whether women should have their rights, which for me is not a debatable subject.

Then I read The Prisoner of Sex. I'd read all of Mailer's work because, after all, I did part of my doctoral thesis on him—Sexual Politics was a doctoral thesis—so The Prisoner of Sex seemed to be very inferior to his usual stuff. It was meanspirited and vitriolic. It made a great noise and a lot of people read it, but I don't think he did himself a service with that book. If you're an important writer, as he surely is, it's a tragic error to pit yourself against any progressive movement or any movement for human rights.

That's an interesting thing about Mailer—he always seems to understand what's the matter with masculine arrogance, but he can't give it up. He's locked into the system. He's not really a progressive person; he's so much more a conservative than a liberal.

GLORIA STEINEM: Norman and I ran into each other at an enormous antiVietnam War rally at the big church up by Columbia in December '71. I had already spoken, he was just coming in, and we were approaching each other in this long, dank, cavernous Gothic hall. I'd become more publicly identified as a feminist because I'd written pieces and taken part in demonstrations and so on, and from about fifty feet away he said, "Oh, Gloria, how are you? I'm glad to see you. You know, we ought to get together. Your people and my people ought to have a talk." I said, "What do you mean by 'my people'?" He said, "You know—women, women." To be funny, I said something like "Norman, I can't do that until you stop thinking your sperm is sacred," only he took it straight and, looking crestfallen, said, "I can't." Then he just walked on by.

JOE FLAHERTY: I didn't pay the fifty dollars to go to Norman's fiftieth-birthday party on January 31, 1973, at the Four Seasons because my friend from the Lion's Head, Frank Crowther, organized it. Wall-to-wall people. You couldn't move, you couldn't get a drink, the din was terrible.

JULES FEIFFER: It's always interested me that two people I venerate very much, Norman and Izzy Stone, seemingly take occasions when people are there to honor and adore them and make certain that the crowd ends up hating them. Which is exactly what happened that night at the Four Seasons. Everybody you'd want to see was there, everybody very happy to see each other, and then Norman got up to talk. He went up to the dais kind of jovial and spunky but quickly became aggressive and pugnacious. He tenses the crowd and polarizes them, as if he feels he operates best as a public figure, not even by dividing the room, but by turning the crowd against him.

LAWRENCE SCHILLER {photographer, book producer, and film director): Even though Grosset had lots of outside confirmation that Marilyn was going to be big, they still didn't know how to do P.R. They tell me they're just going to mail a copy of the book to Time and hope to get a review. I'm screaming, "Send the book in dummy form. We're gonna get a cover when they see it." But no, they said they couldn't do that, so I told them I was sending the dummy. We were having big fights, and meanwhile Mailer isn't talking to me.

I'd already shown the book to a few people, and one of them was a guy at Time. Then he just called—"You got your cover, Larry. But you've got a problem. Your whole credibility is gonna be lost on the Bobby Kennedy thing. Everybody's gonna have to attack it. Mailer's got no credibility."

ROBERT MARKEL {editor in chief, Grosset & Dunlap): After the book came out, Norman had the idea of holding a press conference. I was opposed to it, Schiller was opposed to it, but Norman went ahead anyway, again, putting himself on the spot.

LAWRENCE SCHILLER: I begged him not to do it. Begged him. "You're throwing yourself to the lions," I said. He replied, "No, I'm gonna hold it at the Algonquin. That's the writer's hotel; they'll respect me as a writer."

The two of us walked into the Algonquin and it's a teeny little room, a suite or a small conference room with the press and TV cameras packed in like sardines, and I was furious.

I'm thinking, Oh, my God, we're losing our sales. All the while Norman was challenging the press to go out and get the real scoop, namely, that Marilyn was killed by right-wingers in order to frame Bobby Kennedy. To top it off, he announces he's gonna rewrite the last chapter for the paperback edition—not because he's defeated by the attacks but because he's got new evidence to prove he's right!

DIANA TRILLING: Writers are always suspicious of other writers who make money, so there was nothing special in their suspicion of Norman. But starting in the seventies people began to call him to account—with some basis, I think— for dissipating his energies and writing so many different kinds of things, obviously just for money. Marilyn, I suppose, is the prime example.

NORRIS (BARBARA) CHURCH MAILER: When I'd been in college and pregnant with my first son, Matthew, I'd seen Fig Gwaltney in the English Department. I'd known who he was before I met him. The students knew that he had published ten or eleven books, and we all knew that he was friends with Norman.

By this time I was divorced and teaching art at Russellville High School. One day I'd taken my art class over to see a workshop given by a young filmmaker. Afterwards, somebody came up to me and said, "Guess who was in our class today? Norman Mailer."

He was visiting Fig, so I thought it would be terrific to meet him. I called up Fig and said, "I hear you're having a cocktail party for Norman Mailer. Can I come over?" Finally he agreed, and I went over to their house.

Norman was sitting by the window, wearing patched jeans. I said, "Hi, how do you do? I'm—" "Hello," he said, and turned and walked out of the room. I thought, "Well, I guess he really hates tall women. Forget it."

Anyway, people began to leave, and we went to friends of Fig and Ecey's and mine who live out in the woods. Norman and I stood out on the porch with the brook flowing underneath and talked for about an hour. I wasn't thinking anything, I had no plans. I liked him and he was fun. A few days later I wrote him a funny note and put in some pictures from the local modeling I'd been doing, because I wanted him to remember me.

And did he! He phoned me when he got the pictures and said he was coming back down, and I thought, Terrific!

I left Matthew with my mother, and Norman and I spent three days together at the Sheraton in Little Rock. What did we do during those three days? Mostly stayed in bed.

The next step was several weeks later, when he asked if I'd like to visit him in New York. He came into the city from Stockbridge, and we spent a week together in Brooklyn Heights.

He hadn't been with Carol full-time even before he met me. When he came back to New York at the end of August, he'd already made his decision to leave her. Me, I knew I wasn't going back to Arkansas.

When I decided to go up to New York, there were no conditions, no promises. All he said was "Don't bring any of your Arkansas polyester clothes."

ARTHUR KRETCHMER (editorial director, Playboy): I'd seen The Executioner's Song in typescript in Los Angeles. I went home and read it and called Schiller: "Listen, Norman has done an incredible thing here. He's changed his voice. Those are the most real people in American nonfiction that I know about." Five hours later Schiller called me back: "Norman says Playboy's the only magazine in the country who should even see the book. You're the ones to publish it, because you've understood so well what he was doing." Fine, only then Larry reminds me it'll cost only $100,000.

ALICE MASON (Manhattan hostess and realtor): With each of his wives, going back to Carol Stevens, Norman was a client of mine. He was always looking for an apartment in Manhattan.

I think one of the Kennedys referred him. He always wanted to rent, not buy, but even so I remember when Norris called and asked if I had anything I sort of laughed, because they need space and rentals in Manhattan are very high.

In any case, it was round this time I started inviting them to my dinner parties. Norman had stopped drinking, and his reputation for getting in quarrels was completely contradicted by his new manner. He had mellowed. . . and people recognized that. Certainly I did. I think Norris has made him a different person.

LIZ SMITH: Gore Vidal will always say to me, "Oh, I'm so glad to see you, the woman who thinks Norman Mailer is the greatest living writer." I reply, "I think you've written one of the best books ever written in America, so fuck off, Gore." Then he'll say, "Imagine, Norman Mailer calling a gossip columnist to give his side of the story."

One of the things that made him so angry was that I printed Norman's remark that he wanted his kid to take on Gore's boyfriend—this was at Lally Weymouth's the night of their fight. Gore thought it was beyond the pale, a pointedly anti-gay remark, and certainly from Norman's point of view it was— the suggestion that a fourteen-year-old could lick a pansy. I handled it by saying, "Gore, maybe you're right. Maybe it was a rotten crack. I think it was almost as bad as your calling me a cunt in public for using it."

JACK HENRY ABBOTT (author and prison inmate): When I'd first heard there was to be a book on Gary Gilmore, I didn't know who was writing it. Then I read it was Mailer. I'd been through a lot of the same shit as Gilmore, and my feeling was that no one ever said anything for us, our type of prisoner, the worst kind they've got in prison, so I thought it could be important for him to have an idea of what to pursue.

After The Executioner's Song was published and Norman was on the Donahue show in Chicago, he came to visit me in Marion, bringing a signed copy of the book. I met him in a visitors' room.... He was very gentle at first, and seemed nervous. I don't know at what point when we were talking, but there was a long span of silence. I caught him looking at me and saw the expression on his face, a real compassionate expression, like he'd seen something that made him real sad.

He said, "I showed my agent your letters. You have a book here," although he advised me I shouldn't try to do the book until I was out, because otherwise they wouldn't release me. I got the contract from Random House after The New York Review of Books published my letters.

DOTSON RADER {author): I first met Gilmore—I mean Abbott, I can't keep them straight—at a dinner at Norman's. Norris had asked if I could bring Pat Lawford, so Pat and I went together, and when we walked into the apartment there was this individual—Jack Abbott.

Dinner was a disaster. It's the only time I've ever seen Norman lose control of his own dinner party. He made the fatal mistake of seating Pat next to Abbott, at which point Abbott proceeded to attack the United States as a Fascist country, and then Malaquais, Norman's mentor, joined in. Pat demanded to know if either of them was registered to vote. Both said they wouldn't besmirch their political integrity. Norman had his head sort of down but was eyeing me once in a while, as if giving me a cue to calm Pat down. But Abbott continued his attack. It wasn't a Marxist-Leninist line, it was essentially Trotskyist, and Pat went into an absolute rage. Pointing her finger, she just exploded: ''One of my brothers was president of this country, my brothers gave their lives for this country, so how dare you criticize when you don't even take the goddamn time to vote!"

Norman tried to calm her and everybody else by changing the subject. But nobody wanted to change the subject.

Finally Pat said, ''Well, if you don't like it here, why don't you move somewhere else?" Abbott said, ''I want to." She asked where, and he said, "Cuba." "Good," she said, "I'll pay for your ticket."

JACK HENRY ABBOTT: I'd been with two girls, drinking and talking and listening to music. Then we decided to go to a disco. About three A.M. we went to the BiniBon cafe. After a while we're eating and I see Adan, the guy who gave us menus, looking at me. I turn away from him, trying to ignore him. I keep thinking he's going to come over to the table and upset us, so I say, "Look, if you've really got a problem, let's talk about it someplace else." Adan says, "Do you want to go outside?" That's when I start thinking, He's really coming on....

I get out the door and he says, "Go over there," pointing to the street corner. He was acting like he's got a knife in his pocket.... It was dark and there were broken bottles and garbage all over the place.... I'm thinking he's going to dive into me, take a shot at me with that knife and just jump back out. I hollered at him not to come any closer, and I pulled out my knife. I held it up so he could see it.... I shouted at him again, "Now stay where you are," and I'd just started to say "Don't come any closer" when he came right at me....

I was still yelling at him when he stopped dead on the end of the knife, when he said, "You didn't have to kill me."

DETECTIVE WILLIAM MAJESKI (New York Police Department): I was on the scene right after the stabbing, about twelve minutes later. There was a tremendous amount of blood... literally a pool going from the body across the sidewalk to the curb and out into the gutter.

Later that Sunday, we visited Malaquais and talked to him for about fifteen or twenty minutes. Abbott had been with him earlier that morning, and Malaquais was upset, almost to the point of collapsing. He invited us to search the apartment. After we left, I phoned Mailer in Provincetown.

ALFRED KAZIN: The biggest thing in my life is the Holocaust, and the basic fact about it is that a great many people killed without having any interest in whom they killed. And for my money, Mailer has done exactly the same thing with his obsession with murderers.

That's why, even before the Abbott thing, I'd hated The Executioner's Song. I wasn't impressed with the book's style. For me, it's very simple— I'm opposed to murder. And I don't see how anyone coming from a Jewish background with this terrible history of the Holocaust murders can defend murderers or be that interested in murder.

GLORIA JONES (widow of James Jones): When I first married Jim, he also had a prisoner he was interested in, so it could've happened to us too. Peter Matthiessen has a writer he's trying to get out, Shana Alexander is trying to get Mrs. Harris out. Bill Styron also once took a guy in, and then the guy went out and raped a girl. Jesus, how would you know that letting a guy out he's going to stab somebody?

JASON EPSTEIN (editor in chief, Random House): Over the summer of '83 Norman's agent initiated discussions with Random House, and we arrived at a contract for four major novels. The contract, running for nine years, is unusual since most authors don't want to be committed for that long. Here, though, Norman's O.K. until he's seventy. The $4 million—that's the figure the Times reported—was based on our hunch that Norman would pay out, and, indeed, not only is he one of the best writers in the world, my feeling is that he may be in his prime.

DIANA TRILLING: Actually, I once asked him when he was going to write his War and Peace. He wasn't thrown by the question or by its elaboration. I went on to say that his War and Peace should be a novel of middle-class life, firmly rooted in established society, but that where Tolstoy had made his excursions into history, Mailer should make his excursions into dissidence. Which, of course, is what I'd really like him to do, and it doesn't necessarily have to be a novel; it could be another Armies of the Night, or even autobiography. When you can see that somebody has the capacity to do something so uncommonly good, then you have to hold on to that and say, "Oh boy, please, please come through."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now