Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

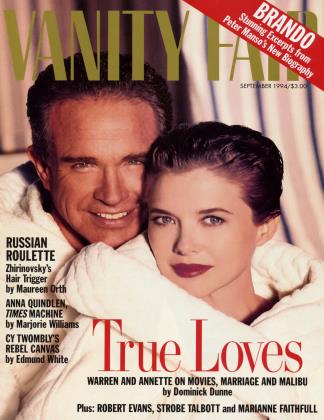

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBRANDO'S WAY

Marlon Brando's electrifying stage turn at the age of 23 in A Streetcar Named Desire put the world on notice that a new genius had arrived. But in the half-century since, his art has frequently taken second billing to his turbulent relationships, his to troubled children, and his mercurial temperament. In these excerpts from Brando: The Biography, PETER MANSO jump-cuts through the chaotic drama of Brando's outsize life

PETER MANSO

Marlon Brando was not the first choice to play Stanley Kowalski, and he was certainly not expected to steal the show from the play's heroine and turn his character into an American icon. A Streetcar Named Desire is the story of a neurotic southern belle, Blanche Du Bois, who after losing her family's estate is forced to seek refuge with her sister and brutal brother-in-law. The drama of her destruction was clearly Tennessee Williams's central vision, mirroring the defeat of southern culture by the harshness and vulgarity of the modem world.

At first, it seemed that two Hollywood stars, Margaret Sullavan and John Garfield, would play the leads. But Sullavan, who was producer Irene Mayer Selznick's choice, failed to win over Williams with her reading. Garfield was a problem, too. The short, tough-talking Group Theatre alumnus was eager to work with Elia Kazan, the director, but Garfield felt the part of Kowalski was not big enough.

Meanwhile, Selznick and Kazan learned of a revival of Williams's early one-act play Portrait of a Madonna in Los Angeles. The play's protagonist, an early version of Blanche, was being played by the British actress Jessica Tandy to excellent notices. Tandy's husband, Hume Cronyn, was the director, and he had in fact arranged the revival in lieu of a New York audition for Streetcar. After traveling to the West Coast, Selznick, Kazan, and Williams unanimously agreed to offer Tandy the role.

Next to be cast were Karl Malden, whose work Kazan knew, and Kim Hunter, who was offered the part of Stella. For the role of Stanley, feelers went out to Burt Lancaster, Van Heflin, Edmond O'Brien, John Lund, and Gregory Peck. Then Kazan got a phone call from the agent Edith Van Cleve, pressing for Brando.

Brando had already been rejected as too young—he was 23, and Williams described Kowalski as nearly 30. Also deemed too "pretty," Brando looked more like a poet than a beer-drinking mechanic. Kazan didn't hang up the phone, however. He knew from Truckline Cafe, a recent Broadway flop, that Marlon had animal magnetism. He also knew that Stella Adler, Brando's mentor, had predicted great things for him, even though he had failed to distinguish himself opposite two of America's leading actresses, Katharine Cornell in Shaw's Candida and Tallulah Bankhead in Cocteau's The Eagle Has Two Heads. Van Cleve admitted that "an audition would prove nothing except that Marlon was a lousy reader," but Kazan nevertheless offered the role to the enigmatic young man, who had grown up in a small town in Illinois and didn't even have a high-school diploma.

The monthlong rehearsal period began in the first week of October. Kazan's method relied heavily on making connections between Williams's script and the actors' personal experiences. Family, religion, schooling, sex, likes and dislikes—all were fair game for his probing, and he dug very subtly in order to draw his actors out. It was a slow process. Brando volunteered little, and Kazan gave him lots of elbowroom. At the end of the first week of rehearsal, Marlon moved a cot into the theater and spent nights there. By the middle of the second week, it looked as though he were losing the battle.

While the other leads were struggling to find their parts, Kazan let Brando proceed "with just muttered snatches of his speeches." It was a "team play," though, and Brando was so intent on his character that sometimes he'd break the tempo completely. The mild-mannered Malden was the first to explode. "We were rehearsing the bathroom scene, the one where I come out and meet Blanche for the first time and Stanley says, 'Hey, Mitch, come on!' Now, as we were working on it, every day would be different. Marlon would come in before you said your line, or way after you said your line, or even before you had anything to say. The beat was all wrong.

"Anyway, we were doing the scene and it was just beginning to go well for me for the first time, like when

you think, Oh, my God, this is it, and— boom—he hit me with one that just upset everything. I said, 'Oh, shit!' and threw something and walked offstage. Kazan said, 'What the hell happened?'

"'I can't concentrate,' I told him. 'I was going along beautifully and all of a sudden in comes this jarring thing. It throws me. It's impossible.' I was furious and explained that it had been happening regularly. He said, 'Wait.'"

Brando eventually began to focus on his lines. Nonetheless, his uhhh sounds still threw his partners off, especially Tandy. The product of a classical British training with almost 20 years' stage experience, she could not relate to Marlon, or his idiosyncratic behavior, or his drums and dumbbells backstage, or his cot, on which he would crash in his street clothes. It all seemed to be epitomized by a split seam in the back of his trousers, an ordinary tear that in the course of several days extended almost down to his crotch. This was brought to the attention of Kazan, who had to tell him to take his pants to the cleaners and have them mended.

A crew of Con Ed ditchdiggers provided Lucinda Ballard, the play's costumer, with the inspiration for the "undesigned" clothing that was to become part of Kowalski-the-icon. "Their clothes were so dirty," she recalled, "that they had stuck to their bodies. I thought, That's the look I want . . . the look of animalness." She modified a half-dozen undershirts, dyeing them a faded red, and created the first fitted blue jeans. "I thought of them as though they were garments in the time of the Regency in France," she said, "which meant fitting the Levi's wet, pinning them tight. I had seven pairs, and I washed them in a washing machine for 24 hours; then Marlon and I went to the Eaves Costume Company. He was up on a pedestal, looking at himself in the mirror, when he insisted on being fitted without any underwear."

Ballard left the dressing room. When she returned, the tailor had finished the basting, and Marlon "almost went crazy. ... He was leaping like a tiger in this costume that outlined his body," the designer recalled. The tailor smiled "as one would about a child," but Brando was unfazed, saying, "This is it! This is what I've always wanted!"

Excerpted from Brando: The Biography, by Peter Manso, to be published in October by Hyperion; © 1994 by Peter Manso.

"Marlon's going to school to learn the Method would have been like sending a tiger to jungle school"

He d created not only a standard of acting but a style; everybody after that wanted to act like Brando

Ballard had "painted" the trousers, strategically deepening the blue at the sides to get a straight up-and-down look, to "accent the maleness, the muscles." She had also removed the interior of the front pockets, which Marlon now pleaded with her not to put back in. "I think Stanley was like me—very physical," he said. "And I think that Stanley would have liked to put his hands in his pockets and feel himself."

By mid-October the script was frozen. About a week later Marlon "suddenly shot up," as Selznick's assistant Irving Schneider put it, in a run-through with both Stella Adler and Hume Cronyn in the audience. Afterward, Cronyn expressed his concern; his wife, he felt, could do better, and he asked Kazan to keep encouraging her. In fact, what he had intuited was that the meaning of the play had been altered; Brando's performance was beginning to shift the play's balance, and would make the young actor the star of the show.

"Perhaps Hume meant," Kazan wrote years later, "that by contrast with Marlon, whose every word seemed not something memorized but the spontaneous expression of an intense inner experience—which is the level of work all actors strive to reach—Jessie was what? Expert? Professional? Was that enough for this play? Not for Hume. Hers seemed to be a performance; Marlon was living onstage. ... A performance miracle was in the making."

On December 3, after tryouts in New Haven, Philadelphia, and Boston, Streetcar opened in New York. Irene Selznick later recalled what happened: "That night was the first time I ever saw an audience get to its feet. And for the first time I saw the Shuberts stay for a final curtain. . . . Round after round, curtain after curtain, until Tennessee took a bow on the stage to bravos." The audience applauded for a full half-hour, and when Brando came out, the house caved in. Backstage, it was a mob scene. Wally Cox, Brando's friend from childhood, managed to fight through the crowds to his dressing room and found Marlon holding a box of chocolates and several telegrams. One read, DON'T MAKE AN ASS OF YOURSELF. MOM. Another, from Williams, brought a smile to his face: RIDE OUT BOY AND SEND IT SOLID. FROM THE GREASY POLACK YOU WILL SOME DAY ARRIVE AT THE GLOOMY DANE FOR YOU HAVE SOMETHING THAT MAKES THE THEATRE A WORLD OF GREAT POSSIBILITIES.

Through the intercession of Georges Pompidou. Brando completed his purchase of Tetiaroa for e $270,000.

Although most critics were overflowing in their praise, not one of them saw that Brando's performance was likely to change the face of American acting. But the cognoscenti knew what was happening. "He'd created not only a standard of acting but a style," said Bobby Lewis, co-founder with Kazan of the newly formed Actors Studio, "which was unfortunate, since everybody after that wanted to act like Marlon Brando."

Williams got the Pulitzer Prize and Tandy won a Tony, but it was Marlon who became the darling of the press. Life, Look, The Saturday Evening Post, Vogue, Mademoiselle, the fan magazines and daily press—all clamored for interviews. Cecil Beaton and lesser lights took his photograph. People pointed him out on the street.

"It took me a long time before I was aware that that's what I was—a big success," he said years later. "I was so absorbed in myself, my own problems, I never looked around, took account. I used to walk in New York, miles and miles, walk in the streets late at night, and never see anything. I was never sure about acting, whether that was what I really wanted to do; I'm still not. Then, when I was in Streetcar, and it had been running a couple of months, one night—dimly, dimly—I began to hear this roar. It was like I'd been asleep, and I woke up here sitting on a pile of candy."

The roar of acclaim eventually made him uncomfortable. As the stress and strain increased and his anxiety worsened, he finally decided to seek professional help. When he approached Kazan for advice, the director recommended his own analyst, Dr. Bela Mittelmann. For the next 10 years Brando relied heavily on Mittelmann, and continued to consult him until the doctor's death in 1959.

As Harold Clurman, Stella Adler's second husband, who had directed Brando in Truckline Cafe, realized, Brando had erected walls of defenses in order not to have to confront

and acknowledge his deepest psychic scars. "Brando's mother was a fine, well-bred woman, but a hopeless alcoholic," Clurman acknowledged. "He suffered untold misery because of her condition, and the soul-searing pain of his childhood . . . lodged itself in some deep recess of his being. ... He cannot voice the deepest part of himself: it hurts too much. That, in part, is the cause of his 'mumbling.' "

Another sign of Brando's insecurity was his confusion about how to play Stanley performance after performance. As months passed, he was not only uncertain but also bored, and his rendition varied depending on his mood. Tandy was trying to keep the show the way they had rehearsed it, and was having one of the hardest times of her life. The reviews and sacks of fan mail, even her Tony, couldn't change the fact that people were coming to see Brando. Streetcar was Stanley's show, and Blanche's defeat was becoming more personal with every performance.

Tandy was the lady, chauffeured to her Upper East Side residence after each performance by a driver whom she'd inherited from Judith Anderson. Brando was the brute, taking off after an evening's performance with a girl on the back of his motorcycle. Selznick, who reportedly saw him fondling a young woman in front of the theater, was appalled: "It just looks terrible to have him out there on the street carrying on at the ticket window."

Worse were his pranks. In the middle of one of Tandy's most emotional speeches, she noticed giggling in the audience. Looking back at Brando, she saw him, stone-faced, shoving a cigarette up his nostril. Another time, the chicken in the birthday scene had mistakenly been undercooked by one of the prop assistants. Marlon gagged onstage, then came off swearing, "I'd rather have dogshit!" The next performance, someone left a mound of mock dog turds on his plate. For weeks afterward he retaliated in kind, leaving joke-store turds onstage in the most unexpected places—in the refrigerator, even in Blanche's trunk.

Brando's most demanding scene came after Stanley is beaten up by his poker pals, when he gives his famous cry "Stella!" which brings his wife back

into his arms. During one performance, he lost it completely. A group in the orchestra laughed nervously, and suddenly, as though something had snapped, he stalked to the footlights and screamed, "Shut up!"

In mid-April 1949, less than two months before the end of his contract, he broke his nose. He was boxing in the downstairs boiler room with a stagehand. "All of a sudden, the guy winds up and throws a haymaker from the floor," Brando told his actor friend Carlo Fiore. "I saw it coming, but I couldn't get out of the way. Next thing I knew, I was flying ass over heels into a pile of wooden crates . . . and I began bleeding from the nose like a stuck pig. ... I put some cold compresses on my beak, but I couldn't stop the bleeding. I heard my cue coming up and ran to make my entrance, and I held my nose, but from the break in the bridge a regular geyser of blood shot about 10 feet across the stage."

He whispered to a startled Tandy, "Broke my nose," and she hissed back, "Bloody fool!" When the curtain came down after two more scenes, it was complete chaos. Irene Selznick shrieked, "No more—this is the end!" Over Marlon's repeated protests, she had him rushed to nearby Roosevelt Hospital. During Brando's absence, Jack Palance, who had been understudying Anthony Quinn in the Chicago production, was brought in.

When Brando was released a week later, he had a different nose. Selznick was aghast, and urged him to have it broken and reset. Marlon refused, claiming that he liked it the way it was. He wasn't perfect anymore; he looked "rugged, like a fighter."

Despite a great deal written about Brando's involvement with the Actors Studio, his participation was sporadic. "He came into the Studio with whatever he had," said founding Martin Balsam, "and he left the Studio with the same thing." For the gritty-voiced Elaine Stritch, it was simpler still: "Marlon's going to school to learn the Method would have been like sending a tiger to jungle school."

Often, he'd sit in Bobby Lewis's class, "always next to some girl whom he couldn't keep his hands off," and finally Lewis laid down the law. "Marlon," he ordered, "you'd better do a scene or you're cut." To everyone's surprise, Brando settled on a scene from Robert Sherwood's Reunion in Vienna. In late 1948, after many postponements, Studio members assembled to watch the scene, and Karl Malden, at Marlon's request, asked them to close their eyes until the cast was ready.

"If Christian was b1ack if he was Mexican. he if he was poor, he wouldn't he in this courtroom."

When the eager group opened their eyes, they were astounded. Instead of the ruffian from Streetcar, they saw a real prince in uniform, with a monocle. Marlon's speech was perfect, his Austrian accent absolutely on target, and with his first line he got a big, appreciative laugh that worked like a "blood transfusion," Lewis recalled. "It was as if he realized, Oh, my God, I can really do this. I can be funny. He was like young John Barrymore."

1960: MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY

After Streetcar, Brando never returned to Broadway. Over the next five years, he made six acclaimed films, the last of which, On the Waterfront, brought him an Academy Award. Kazan, who directed it, as well as Viva Zapata! and the movie version of Streetcar, called Brando's scene in the backseat of the car with his brother, played by Rod Steiger, "the finest thing ever done by an American film actor. " John Gielgud, who acted with Brando in Julius Caesar, told Joseph Mankiewicz, the film's director, "This young man is magnificent, " and he begged Brando to play Hamlet on the stage in England for him. During the second half of the 50s, however, Brando made less and less artistically significant films, and his ego and personal life seemed to affect his career more and more. During Viva Zapata! he became involved with a Mexican actress named Movita Castenada, who would become his second wife. During the making of One-Eyed Jacks, a much-postponed, overbudget Western he directed and starred in, he was in court battling his first wife, the exotic actress Anna Kashfi. By the time he agreed to star in Mutiny on the Bounty, his difficult temperament was already an issue.

MGM's remake of the 1935 classic, budgeted at around $12 million, would ultimately cost more than $25 million and bring the studio to its knees. The picture marked the pinnacle of Brando's selfindulgence. During the laborious 13month shoot, he outdid himself with time-wasting tantrums, on-the-set script doctoring, and flagrantly irresponsible behavior. But if Mutiny represented a turning point in his professional life, it also introduced him to Tahiti, the island paradise that would become his refuge from Hollywood, and the symbol of his hopes.

To play Fletcher Christian, Clark Gable's role in the original, Brando was paid $500,000 against 10 percent of the gross receipts, $5,000 for every day the film went over schedule, and reportedly $10,000 a week in expenses. He was also guaranteed consultation rights for the film's final sequence, but he would wield a free hand in making script changes throughout the picture.

Carol Reed, the distinguished British director of The Third Man, was signed to direct. For the role of Captain Bligh, Reed and producer Aaron Rosenberg cast Trevor Howard, and Richard Harris, the Irish stage actor, was assigned the role of John Mills, the manipulative mutineer. With 95 percent of the film being shot on Tahiti, the movie would feature not only an international cast but also a 350-ton replica of the Bounty.

Arriving on Tahiti in late fall 1960, Brando rejected the stately manor provided by MGM in favor of a traditional thatched fare. He also began wearing a sarong and soon adopted the native custom of wearing a frangipani blossom behind his ear. "I love it down here. I'm not Brando the star, I'm Brando the man," he told assistant director Ridgeway Callow. Removing himself from the cast and crew, Brando liked to hold gatherings at his fare in the evenings. Alice Marchak, his secretary, would bring in local musicians, and Brando would reportedly play drums into the night with them, sweat pouring down his forehead, his face expressionless.

Brando and other members of the company also took up flagrantly with the local women. "It was out of control," said one staffer. To the crew's amazement and delight, the vahines weren't after money or husbands but merely romance. Old, fat, thin, alcoholic, or infirm, they loved to invade male cast members' apartments. Soon an epidemic of venereal disease—the so-called MGM flu—swept through the cast, crew, and extras. For Brando, sexual partners had never been a problem, but what he found particularly attractive about these women, aside from their extraordinary skin, was that by and large they "made no attempt whatsoever to tie him down," according to Bengt Danielsson, a technical adviser on the movie.

Most of the Tahitian women cast in the film had minor, nonspeaking parts, but there was one role of substance: Maimiti, the chief's daughter and Fletcher Christian's lover. Reed, Rosenberg, and Brando auditioned 100 candidates, finally choosing 19-year-old Tarita Teriipaia, a dishwasher at the restaurant Les Tropiques. Part Chinese, part Polynesian, Tarita was also a dancer in the floor show at Les Tropiques, which was managed by her Danish boyfriend, John Christiansen.

Heimata "Charlie" Hirshon, her former boyfriend, had to bring Tarita by three times before Reed and Brando made up their minds. Brando had first lobbied for Anna Gobray, another dancer. Then he turned to Vaea Benet, a teenager who also danced at Les Tropiques. But Tarita had caught his eye.

Soon Marlon had invested Tarita with his Rousseauesque notions of purity. While he had several other girls servicing him in what was basically a turnstile arrangement, he would "never go to bed with her," said Nick Rutgers, an American expatriate who served as a production coordinator. "He would sleep on the floor and she'd sleep on the bed. They'd hold hands, that kind of thing." Once the affair with Tarita was consummated, though, Brando continued his romance with another Tahitian dancer and juggled the two women.

Brando's professional relationships with the other actors were constantly on the verge of flaring into open hostility. His habit of forcing multiple takes quickly pushed Richard Harris past the breaking point. In one scene, according to Jimmy Taylor, one of the costume men, Brando was especially flat and finally said, "I don't know if it's going to work or not." Harris blew up. "Damn you! Look at me! Act! Who the hell do you think you are?"

It was the same with Trevor Howard. "Brando never knew his lines. He just made them up as he went along and always to his own advantage," said Hirshon. "There was one scene when Marlon asked for a retake maybe 18 times, because in 17 of the takes Trevor was better. But after they'd done it over and over, Howard got fed up, and suddenly Brando felt he was better, so the 18th take he kept."

In February, with only one-third of the footage shot, the cast and crew gave up in the face of relentless storms and departed for Los Angeles, where filming would continue at MGM's Culver City studios. Several of the Tahitian women, including Tarita, were installed at the Hotel Bel-Air, where Brando continued his amorous pursuits.

The cast was scheduled to regroup in Tahiti the third week in April, but Brando was delayed. On April 19 the actress Rita Moreno, with whom he had had a long on-and-off affair, suddenly re-entered his life by trying to take her own. "The peppery Puerto Rican actress was rushed to a hospital from the home of actor Marlon Brando Wednesday after she took an overdose of sleeping pills," stated an L.A. news story.

Brando was soon winging his way to Tahiti. During this same month, he telephoned Anna Kashfi, his ex-wife and the mother of his son Christian, to let her in on the secret he'd managed to keep for nearly a year. "He told me he had married Movita the previous summer and that he wanted their son, Miko, to be a brother to Christian," she recalled. "He suggested that I and Devi [her preferred name for Christian] should move to Tahiti to live." If Brando thought the phone call would appease Kashfi, with whom he was involved in a long custody battle, he was sorely mistaken. Instead, the fights in court continued.

Meanwhile, the troubled nature of the Bounty production had become one of the worst-kept secrets in Hollywood. "The multimillion-dollar epic is about one-third completed amid laments from MGM that costs have soared far beyond the budget," Hedda Hopper wrote in the Los Angeles Times. MGM executives were preparing to delegate the blame. But while Brando could be fingered and even set up, he couldn't be fired. Instead, director Carol Reed took the fall. At the end of February, he was replaced by Lewis Milestone.

On June 29, Brando left Tahiti for a 30-hour visit to L.A. to battle Kashfi in court in Santa Monica. The issue once again was Christian— specifically, Brando claimed, because a distraught Kashfi had barred the actor from seeing his three-year-old son in April. Immediately after the hearing Brando left for Tahiti.

On August 1, with only half the film shot, Brando's $5,000-per-day overtime fee went into effect. The sum would eventually reach $750,000 above and beyond his $500,000 base pay and per diem rate. Charlie Hirshon remembered Marlon's shows of temper. "He'd just go, 'Oh, fucking shit!' and take his costume off and walk away. It happened for any reason—either he was fed up with the directing or the stuntman wasn't doing something correctly; someone made eye contact when he was saying his lines; or he was too hot; or he wanted to go home and screw. Whatever it was, he'd walk off at 10 in the morning and we couldn't shoot anymore that day."

The only thing that interested him besides his women was Tetiaroa, an atoll that he had spotted during location scouting. Situated some 35 miles north of Papeete, Tetiaroa was composed of 12 small motu, or single-reef islets, enclosing a central lagoon. The property was not for sale, Brando learned, but he asked several people to look into the possibility of his buying it.

Meanwhile, MGM would suffer an operational deficit and a major drop in stock and would replace Joe Vogel as president, citing as the major factor "the full anticipated loss" on Mutiny on the Bounty. Sol Siegel, MGM's production chief, reportedly threatened to sue Brando for "throwing" his performance and trying to force his own ending on the picture. Brando publicly challenged all charges of misbehavior.

Late in 1983, Brando embarked on an extraordinary venture: giving acting lessons to Michael Jackson.

There was also talk that Brando had tried to add homosexual overtones to the role of Fletcher Christian. Brando's foppish portrayal annoyed Richard Harris, particularly during a scene in which Brando was supposed to slap Harris in the face. Brando merely flicked his wrist. Harris, taking the gesture as an insult, responded by kissing Brando on the cheek. On the next take, Brando tapped him again. "Shall we dance?" Harris yelled, and stomped off the set. The following day Brando stubbornly played the scene the same way, and Harris once again took his leave, this time refusing to reappear for three days.

Harris later told the American press that when he finally returned Brando approached him and said, "Dick, you shouldn't have done it.

I'd like you to know this: I'm the star of this picture and you're op posing me. Remember that, please."

"For six weeks Brando sabotage*

[the production]," Hedda Hoppe wrote in December 1961. "He'd sho\ up on the set when called and asl 'Where shall I stand and what do say?' Then he'd speak his lines in meaningless monotone. ... A millk words have been written about wha wrong with Hollywood. Well, her* the answer."

In August 1962, Tarita returned Los Angeles along with several ot cast's mutineers for a few days of reshoots. Milestone stayed on for appearance's sake, but refused to go near the camera or Brando. George Seaton, an MGM contract director, was nominally in charge, but, aware of the stigma attached to the project, he had agreed to take the assignment without pay and only on the condition that his participation not be publicized or credited. Essentially, Brando directed himself, and his death scene was more bizarre than anything he'd done to date.

"He was lying there naked," said Jimmy Taylor. "The makeup man had put bums on his exposed flesh, and I had this fabric with simulated burn marks that I was going to paste on his skin to cover up his genitals. Then he asked, 'Why doesn't my crotch burn?' I said, 'Well, I can't do that, Marlon. We've got a censor problem. Maybe we can use makeup to blend this in with the pants.' 'No, no. If the pants are going to burn, so is the cock. You've got to show it.'

"I then got to Rosenberg and explained what Marlon was demanding. Aaron's reply? 'Well, he's shown his cock to everybody else—now he wants to show it to the American public. Don't worry, I'll put a tarp over him.'

"I'd never seen anything like it in my entire career," Taylor added.

"He started at such a violent pitch that I said to rnvseff~ Mavbe I cannot work at iii level of this actor.'"

"An actor, a star wno is prepared to lie out in the middle of the stage with his cock hanging out. The whole crew was there—there must have been 60 or more people standing around— and he had no embarrassment."

To help Brando prepare for the scene, Seaton told him that when a person is severely burned the loss of body fluids leaves him in a state similar to that of being frozen. "Get me a couple of hundred pounds of cracked ice," Brando ordered. "Spread it out and throw a sheet over it."

Ridgeway Callow brought out the ice, and Brando lay down on it for 45 minutes. "I want to get the death tremors," he

announced as his skin turned blue. Through chattering teeth he gave an enormously effective rendition, even though he couldn't remember his lines. This time, a human cue card in the person of Tarita was utilized. The camera was shooting over the back of her head, and Brando was supposed to murmur a couple of words in Tahitian as he died. As Callow recalled, "We got a grease pencil and wrote the words on Tarita's forehead."

Brando attended the star-studded, $100-a-ticket benefit opening in Los Angeles with Movita. Rosenberg escorted Tarita, who seemed indifferent to the presence of Marlon and Movita. Marlon then made an appearance at the New York premiere, where die-hard film buffs booed him. After 15 minutes of the film, he left.

Around Christmas, Brando volunteered to be present at the premiere in Tokyo, and arranged to meet up with Tarita. She was four months pregnant, and he asked the wife of one of his Tahitian friends to accompany her to , where the question of an abortion could be discussed.

Tarita refused to go through with ⅛ it. After the birth of a son on May 30, 1963, in Tahiti, Tarita told the friend's wife, "I had my baby and Marlon was very mad after me." i The baby was named Teihotu, but he was not given the Brando name. Later, Brando would change his mind, laying his reluctance to acknowledge paternity on the complications of his ongoing legal problems with Kashfi; at the time, he probably did not want to upset Movita, either.

In early 1967, through the intercession of French premier Georges Pompidou, Brando completed his purchase of Tetiaroa for $270,000. During his sporadic visits to Tahiti, usually a week or two in duration, he would stay with Tarita and their son in the waterside compound he had bought for them in the wealthy Punaauia section, just south of the Papeete airport. But often he would make the two-hour voyage across open seas to Tetiaroa to wander the bone-white beaches of the atoll alone.

1972: LAST TANGO IN PARIS

Brando had hit the $1 million salary mark with The Fugitive Kind, a failure based on Tennessee Williams's play Orpheus Descending, and then for a decade he found himself trapped in mediocre—or, at best, interesting-films with some of the greatest directors in the world, from Charlie Chaplin (A Countess from Hong Kong,) to John Huston (^Reflections in a Golden Eye,). During this period, Montgomery Clift, Brando's rival as an actor for many years, said, 'Marlon isn't finished yet. He's just resting up. He'll be back—bigger than ever." Indeed, Brando's artistic integrity was redeemed temporarily by two films he made back-to-back in the early 70s, The Godfather and Last Tango in Paris.

When the Italian director Bernardo Bertolucci gave Brando the script of Last Tango in Paris to read, he emphasized that he wanted much of the movie to be improvised. Hoping to explore questions of isolation, despair, and sexual obsession through Brando's character, he asked the actor about his memories of his childhood, his feelings about his parents, his deepest sexual fantasies. Remarkably, Brando seemed to open up to him.

In due course both acknowledged their experiences with psychoanalysis. As the director explained, "I wanted him to forget [the character of] Paul and remember himself and what was inside him. For him it was a completely new method. He was fascinated by the risk, and afraid of the sense of violation of his privacy." Brando and Bertolucci developed a pattern. Each day they huddled privately for several hours to discuss what they'd been thinking about, and their talks seemed to evolve into mutual psychotherapy sessions, with each man energizing the other.

"He was wonderful," Bertolucci later said. "I always fall in love with my actors and actresses, but especially with Marlon." Once, holding a photograph of Brando, the director exclaimed, "Isn't he beautiful? Just look at that face." He then brought the picture to his lips and kissed it. "Oh, Marlon," he said, "you are good enough to eat."

Brando's character is a world-weary, desperately lonely, and disillusioned man who, after the suicide of his wife, becomes obsessed by Jeanne, a beautiful 20-year-old woman. In the opening scene, in which Brando is standing on the Bir-Hakeim bridge while the Metro roars by overhead, Bertolucci chose to shoot the actor's back as he clamped his hands over his ears. "I can't believe this," Brando told an assistant director. "Bernardo is completely crazy. He wants me to play this with my back to the camera." However, he went along and did the director one better. Brando not only put his hands over his ears but also erupted in a heartpiercing scream. "I was shocked," said Bertolucci. "He started at such a violent pitch that I said to myself, 'Maybe I cannot work at the level of this actor.' I was very scared."

Several days into the shoot Brando finally met Maria Schneider, the actress chosen to play the young woman. Schneider was the illegitimate daughter of French stage actor Daniel Gelin, one of Brando's apartment-mates during the summer of 1949, which he spent in Paris. Now Brando was to enact on film an obsessive, sadomasochistic affair with his old friend's daughter, who was not yet 20. The director had interviewed more than 100 actresses, and although Schneider had little acting experience—she'd left home at age 15, danced in a French stage comedy, worked as Brigitte Bardot's stand-in, and appeared in two small movie roles—Bertolucci thought she was the personification of the hip but bourgeois student. "She was a Lolita, but more perverse," he explained, adding that when he had asked her to take her clothes off during the screen test, "she became much more natural."

Later there would be much speculation about whether Schneider and Brando actually had an affair. Schneider confided to her father that she and Marlon had indeed begun one. It would seem that there was some residual bitterness, however, because later Schneider was quite outspoken about Marlon's age and flabbiness. "I never felt any sexual attraction to Brando," she said. "He's almost 50, and he is only beautiful to here," she added, gesturing to her neck. "He was very uptight about his weight; he kept pulling curtains whenever he changed clothes."

During the filming, as Bertolucci watched Brando with Schneider, he urged them to become more sexually explicit. "You are the embodiment of my prick," he told Marlon. "You are its symbol." Brando would diminish the importance of the movie by exclaiming in an interview, "I don't think Bertolucci knew what the film was about. And / didn't know what it was about. He went around telling everybody it was about his prick!"

Schneider, meanwhile, claimed that she understood what was happening, since she shared the same sexual proclivities that both Brando and Bertolucci were rumored to have. In her usual, unflinching way, she announced that she and Brando got along together because "we're both bisexual and it's beautiful." The sexual scenes, she added, were a way of "acting out Bernardo's sex problems."

On the day that Brando was to give his monologue over the body of his dead wife, Bertolucci saw new and extraordinary depths in his affect. As scripted, it was a genuinely moving and painful

episode, but afterward, Brando acknowledged that the scene had brought him to real anguish, because, as Daniel Gelin recalled, "he was remembering the death of his mother." Dodie Brando had tried to commit suicide at least once, and there was also the love and grief mixed with anger and a sense of betrayal in his character that paralleled Marlon's own ambivalence toward his mother. All of it pushed him beyond anything he'd ever done before. In front of the camera his pain, grief, and indignation were extraordinary, as if the inner Brando, propelled by a spring, had jumped out of a box.

For the scene in which Paul sodomizes Jeanne, the butter was Bertolucci's idea. "Get the butter!" Brando commands before he mounts Schneider from behind and forces her to repeat vile epithets against convention, religion, and the idea of family. "I'm going to tell you about the family. . . . Repeat it after me. . . . Holy family, church of good citizens. . . . The children are tortured until they tell their first lie. . . . And freedom is assassinated. . . . Family . . . you fucking, you fucking family," he rants in an orgasmic gasp as Schneider sobs out the black litany until he falls spent on top of her.

Bertolucci pushed Brando even harder when it came to the monologue in which his character was to reveal his past and cry with bitter revulsion. "Give me some reminiscences about your youth," the director instructed him when the moment came, and then told his cameraman to load 900 feet of film. "The scene was completely improvised, and Marlon was truly naked at that moment," he later explained. "I had no idea how long it was going to last."

The improvisation was framed by Schneider's asking Brando's character about his memories of America. Brando paused and rubbed one eye, as if he were going into a self-induced meditation.

"Oh," he said with a sigh, "my father was a drunk, tough whore-fucker, barfighter, supermasculine, and he was tough. My mother was very, very poetic, and also a drunk. And uh-h . . . All my memories of when I was a kid was of her being arrested, nude. We lived in this small town, a farming community. ... I'd come home after school. . . . She'd be gone, in jail or something." He stopped after a while, as if blocked. "I don't know,

I can't remember very many good things." Then he began to describe another image from his troubled boyhood—the spring he was thrown out of military school and returned home in shame, totally at the mercy of his father's stem discipline. In contrast to earlier scenes, in which he had faked his sobs, real tears welled in his eyes.

When he mentioned his old dog, Dutchie, his voice faded away. It was not another bit of business. He was unable to go on. In the silence, Bertolucci exclaimed, "Wonderful, wonderful."

Last Tango was presented on October 14, 1972, the final night of the New York Film Festival. Pauline Kael registered the shock of the audience by announcing that Tango was "the most powerfully erotic film ever made, and it may turn out to be the most liberating." She asserted that the date of the screening "should become a landmark in movie history comparable to May 29, 1913—the night Le Sacre du printemps was first performed—in music history. . . . Bertolucci and Brando have altered the face of an art form."

Last Tango would prove to be a true gold mine for Brando, since he earned a percentage of the gross. "It cost about $1.4 million to produce and its breakeven was about $3 million," explained producer Alberto Grimaldi. "The movie grossed more than $45 million, and it was still making money 20 years later. I would guess that Marlon earned at least $4 million from it, probably more."

SOCIAL CONCERNS

On March 27, 1973, Liv Ullmann and Roger Moore stood onstage at the annual Academy Awards ceremony, reading the nominees for best actor: "Marlon Brando for The Godfather, Michael Caine and Laurence Olivier for Sleuth, Peter O'Toole for The Ruling Class, and Paul Winfield for SounderThen Ullmann announced, "The winner is .. . Marlon Brando!"

As the audience broke into thunderous applause, a statuesque Native American woman made her way to the podium. The clapping dwindled away into gasps of surprise and audible groans when she moved to the microphone. "My name is Sacheen Littlefeather," she said. "I'm Apache, and I am the president of the National Native American Affirmative Image Committee. I'm representing Marlon Brando this evening, and he has asked me to tell you . . . that he very regretfully cannot accept this very generous award. And the reasons for this are the treatment of American Indians today by the film industry and on television in movie reruns."

"There was one scene when Marlon asked for retake maybe 18 times, because in 17 of the takes revor was better.

As the broadcast's closing credits rolled across millions of TV screens, Littlefeather handed the press copies of Brando's 1,000-word statement scoring America and the film business alike for their treatment of Native Americans. She also confirmed that Marlon would soon be on his way to Wounded Knee, South Dakota, to support the American Indian Movement (AIM) protesters who had been under siege there for four weeks.

As it turned out, Brando did not go to Wounded Knee, but for more than a decade, beginning in the early 60s, he committed himself to protesting social injustice. He rallied with Martin Luther King Jr. 's Southern Christian Leadership Conference, CORE, and, later, the activist Black Panthers. But most of all, he pledged himself to supporting Native Americans. He was shot at in Gresham, Wisconsin, during the takeover of an Alexian-brotherhood novitiate by a group of Menominee Indians. Throughout this time, he was inordinately generous with not only his time but also his money; his contributions were estimated to exceed $500,000. Unhappily, as a result of what AIM leaders Dennis Banks and Russell Means saw as Brando's unrealistic expectations for social change, by the end of the 70s his participation proved as frustrating to the actor himself as to the Indians.

LAWSUITS AND DREAMS

During the 1980s, Brando became more and more reclusive in his Los Angeles home on Mulholland Drive, and seemed to enter into more lawsuits than movie negotiations. After Apocalypse Now in 1979, his performances were taken less than seriously, and he frequently voiced his desire to make money and support his growing family by means other than acting.

With the release of Superman II in 1981, Brando revived his long-standing 1978 lawsuit against the film's producers, in the amount of $50 million. On April 6, 1982, the suit was quietly settled out of court when producer Alexander Salkind and Warner Bros, agreed to pay Brando a share of both Superman films' earnings estimated at between $10 and $15 million. Brando, wrote one columnist, "made more money in the courtroom . . . than he did on screen."

A few weeks later, Brando filed a suit against Francis Ford Coppola, who had helped him win his second Oscar with The Godfather. The issue was Brando's 11.3 percent of the adjusted gross from Apocalypse Now. Brando claimed that in addition to $8 million in residuals he was due $40 million in punitive damages.

In March 1983, Brando tried to organize his life by hiring yet another assistant, someone to run things at his house on Mulholland Drive, including construction and security. This time he turned to Tom Papke, a techie with a background in films, computers, and electronics, whom he had met through a friend. Papke remained in Brando's employ for 14 months, after which he would work for the actor on individual projects for another six years. As with everyone coming into contact with Brando, he would experience the usual periods of excommunication and temporary disfavor. But what struck him the first day he reported for work was the inspired craziness of the actor's lifestyle.

"The first thing he said was 'I want to see if you're really as good as I think you are,"' Papke recalled. "'Do you have lockpicks?' I was afraid to say yes, but of course I did, and he led me outside to the building where he kept his motorcycles, the welding gear, and tools. It took me a while—two steel doors. I was standing there picking the lock, the lock went click, and then he said, 'Can you open anything else?' Eventually he had me working on all the locks in the whole place."

The 48-year-old Papke was exactly Brando's kind of guy, zany enough in his own right, bright, loyal, eager to please, but also unconventional, even though his usual outfit was a Botany "500" suit. "Throughout my relationship with Marlon, what he wanted to do was use technology to make lots of money," said Papke. "Money, though, wasn't ultimately what was pushing him. What motivates Marlon is the opinion of other people, and he wanted to do something on his own, a high-tech project that would gain him the respect of the world as someone of intellect and high achievement, not just some actor."

By Hollywood standards Brando was not living opulently. The main house of what was often described in the press as a sprawling Beverly Hills estate was in fact quite modest—3,000 square feet of open, whitewashed Japanese-style space. Yet, as Papke was beginning to see, the actor's impulse buying could be disastrous. On the weekends, spur of the moment, Brando was capable of sending Yachiyo Tsubaki, a Japanese heiress who was his serious girlfriend at this time, down the hill to pick up $2,000 worth of tape recorders. When it came to cameras, radio equipment, and tools, he was unstoppable.

"I could be browsing somewhere," recalled Papke, "then come back to Mulholland and say, 'Gee, Marlon, I saw this device which I think is pretty nifty.' He'd ask, 'What's the phone number?' and grab the phone. 'Hello? This is Marlon Brando. Do you have—yes, Marlon Brando. No, I really am Marlon Brando. . . . Uh-huh. Listen, do you have so-and-so?' "

Just for effect, Brando would sometimes dribble food out of his mouth while eating. Like a musician challenging his audience, he might also let loose long, rippling, glissando farts in the middle of a conversation, waiting for the other person's reaction. The apotheosis of Brando's "poo-poo, ca-ca, wee-wee stuff' was called "Dial-a-Fart." Brando and Papke were sitting around one day trying to think of something to do with the newly available 976 telephone numbers, a local variant of commercial 900 numbers. "Why not Dial-a-Fart?" said the 11-year-old daughter of Brando's personal assistant, Caroline Barrett. "You'd have to identify famous movie stars' farts."

Brando came unglued. "We were going to call up Charlton Heston and see if he'd fart for us," Papke recalled. "Marlon would call up all the movie stars."

"We rig it up so people would fart into the phone, and there's another contest there," said Brando, excited. "We'll call it Fart of the Week, Fart of the Month, Fart of the Year. And we could give a big prize."

Dial-a-Fart was a recurrent topic of conversation for weeks. Brando thought of sending a safari to Africa to record elephant farts. This, said Papke, degenerated into talk of the smallest audible fart, a mouse perhaps. Finally, with the solemnity of negotiating a film deal, Brando called Allen Susman, his attorney, to discuss the legalities of the plan. "Here are our ideas," he told Susman, running down Dial-a-Fart from A to Z. "What are the liabilities? The federal laws here, and the local ones?"

Soon the attorney was laughing, said Papke, who was on the extension. "Finally he said, 'Marlon, if you'll excuse the expression, if anyone gets wind of this, you're finished in Hollywood.' And then, click, he hung up the phone."

An equally comic scene occurred when Brando, in one of his frequent attempts at losing weight, decided to try stretching exercises and asked Papke for help. He had already purchased a rotating hoopframe device and special hooked boots, from which he would be suspended, but, due to his girth, he found that he was unable to flip over and hang upside down. He sent two of his employees out to the garage for a winch that had been mounted on his truck, then had them bolt it to the ceiling of his bathroom.

"In the meantime," Papke recalled, "Yachiyo had come over to cheer him on. She was all in favor of it, since she'd been making him every kind of salad, even though he'd been paying employees from McDonald's in the Valley to come up on the sly and toss him stuff over the fence. You'd find the mess in the morning. Several Big Macs, French fries—the whole thing."

By late in the afternoon, after six hours had been spent locating the joists in the ceiling and setting up a 12-volt power supply for an on-off switch, Brando's two helpers had the apparatus in place and had tested the mounting. Soon Brando was hanging in the air. A new problem quickly became apparent, though. "He was hanging head down," Papke explained, "and because of his weight the blubber started to roll forward, almost choking him. He was coughing and muttering, unable to speak."

They immediately lowered him to the floor. Brando, however, was determined to stretch, and the solution he proposed was to try it horizontally. Detaching the winch from the ceiling, the two employees fixed another heavy screw eye into the wall of the bathroom opposite the doorway. Once again, Brando readied himself. "He wanted Yachiyo to straddle the doorway and hold on to his hands while the winch pulled from the opposite direction," said Papke. "But the winch was so strong that she couldn't hold on. But Marlon wasn't letting go either, so Yachiyo was being pulled through the door into an almost inverted position. When he finally released her, she popped through the doorway like a cork, and the whole megillah collapsed."

Then there was Marlon's touching attempt to reach out to his son Christian, who had had serious problems with drugs and drinking, by proposing that the two of them, together, get their high-schoolequivalency diplomas. Brando had never graduated from the military school he attended, and Christian, now 25, had gotten only as far as the 10th grade. Unfortunately, after only several weeks, their lack of application sank the program.

Just before the holiday season of 1983, Brando embarked on an extraordinary new venture: giving acting lessons to Michael Jackson. Brando's connection to the singer had come through Quincy Jones, whom he had known since the late 60s. "He wanted to take his kids to Michael Jackson's concerts, especially when Cheyenne [Brando's daughter by Tarita] was visiting from Tahiti," said Pat Quinn, an actress who was for years a friend and assistant of Brando's.

Quincy Jones had also been indirectly involved in the hiring of Miko, Brando's son with Movita, as Jackson's bodyguard. In January 1984, Miko saved the singer when his hair caught on fire during the filming of a Pepsi commercial. It was not unusual for Miko to bring Jackson up to Mulholland, and soon the young singer regarded Brando not merely as a father figure but as an idol. Jackson taped their sessions.

After a year of working for Brando, Pat Quinn was told that "there was no more work." The reason Marlon let her go, she later felt, was that Yachiyo had become jealous. "That's when he arranged for me to work as Michael's secretary," said Quinn, "and he took me over to the house where [Jackson] lived with his parents in Encino."

When they arrived, Jackson greeted them at the door dressed in a Pinocchio outfit, complete with long nose. "It was quite surreal," said Quinn. "He was standing there like a character you see at the Disneyland parade, and he spent the entire meeting in this I getup. Marlon's idea was that since Michael was starting a production company I could get in on the ground floor. But after six weeks I couldn't bear it any longer. One day I asked myself, Wha am I doing here? I was in M chael's bedroom, with him lookii over my shoulder as I was changi his chimp's diapers. That's whei decided to leave. But Marlon was rious at my decision. He was su: could have had this wonderful ca in Jackson's film company."

Brando's failure to lose weigh reported by British tabloids as th son for Yachiyo Tsubaki's stormii of the house during the spring c after devoting her life to Marlon for seven years. But more than likely it was the culmination of many disputes and Brando's increasing interest in his housekeeper, Cristina Ruiz, a young Guatemalan.

When Cristina became pregnant, Brando summoned Tom Papke and told him to locate a house in the San Fernando Valley to buy and to work out the financial and legal arrangements. On May 13, 1989, Brando accompanied Cristina to Saint John's Hospital in Santa Monica, where he watched her give birth to a daughter named Ninna Priscilla Brando. "I can't believe I can feel all this love at my age," he reportedly announced.

1990: THE SHOOTING AND THE TRIAL

Two hours after Marlon Brando reported a shooting at his home on Mulholland Drive on the night of May 16, 1990, homicide detectives arrived at the house. Paramedics had pronounced the victim dead of a single .45-caliber gunshot wound to the face, and Christian Brando, Marlon's 32-year-old son, had been handcuffed and was on his way down to the station for questioning, having blurted out to the police that he'd accidentally killed his pregnant half-sister Cheyenne's Tahitian boyfriend.

Marlon Brando explained to a detective that Cheyenne, her mother, Tarita, and her boyfriend, Dag Drollet, had been living in the house at his invitation. Cheyenne had been having severe psychological problems for the past year, owing to an automobile crash and resultant plastic surgery. The actor had brought the girl from Tahiti to Beverly Hills a week earlier to see a psychiatrist.

"He cannot voice the deepest part of himself: it hurts too much. That, in part, is the cause of his mumbling."

That evening Christian had visited the house for two reasons, Brando said: to bring his pistol for safekeeping and to take Cheyenne out to dinner. About 15 minutes after their return, Brando became aware that they were in the living room. He had not heard the shot, but in the living room he found Christian holding a large handgun, and his son told him that he had just shot and killed Dag.

Nine months later, on February 26, 1991, defense attorney Robert Shapiro (who is currently defending O. J. Simpson) called Brando to the stand to testify at his son's sentencing hearing. As the actor rose from his seat, his face was expressionless. For the most important performance in his life, he had chosen to wear a rather old, somewhat frayed-looking black turtleneck and a rumpled blue cashmere blazer, its tailoring pulled out of shape by his enormous girth. Slowly he walked across the front of the courtroom to the witness stand. The clerk completed the recitation of the oath with the usual "so help you God?" I will not swear on God," announced abruptly. "I will wear on God, because I don't bein the conceptional sense and in nonsense. What I will swear on is children and my grandchildren." 'We have a different oath we can e him," the judge said quickly, sturing to the clerk.

After the oath, Brando sat in the itness chair, but because of his 'eight—more than 300 pounds, it ippeared—he had to shift sideways it times, his arm draped over the railing to support himself.

Announcing his name as "Marlon Brando Jr.," he responded in a muted, almost choked voice to Shapiro's request that he describe Christian's childhood years, including "any traumatic experiences." Brando began a rambling narrative about his relationship with Anna Kashfi. He called her "as negative a person as I have met in this life," adding, "I think the tincture of what her character is can be encapsulated in the fact she is not in this courtroom today."

Brando told the court that he had married Kashfi ("probably the most beautiful woman I have ever known") because she was pregnant and he didn't want his child to be illegitimate, but that the marriage soon ended. His voice grew angry as he described how she had lied to him about her Indian parentage.

He recalled one ugly battle with Kashfi after she had gotten a court order requiring him to send a chauffeured limousine whenever Christian was to be brought to Mulholland Drive. One time he drove himself and Anna became irate with his explanation that he had done so because the limo was late. "She took a fencing foil, and beat me on the back with it, and it hurt a lot. I pretended that it didn't mean anything at all. ... I have never said anything bad to Christian about his mother. I have always tried to tell him that his mother was ill."

He announced, "I think perhaps I failed as a father," and though "the tendency is always to blame the other parent," he admitted that "there were things that I could have done differently had I known better at the time, but I didn't."

Asked how far Christian went in school, Brando didn't answer directly. "As far as I am concerned, Christian is still going to school." He then spoke warmly about his son's going to technical school, where "his tactics in welding were very good." He was invited to be a teacher, "for which I was very proud, and he had to take his written tests, which scared him to death."

"Some people have reported that Christian is the son of a rich and famous man. What would be your comment to that?" Shapiro asked.

Now Brando flared up again. "Then either they are a lying son of a bitch or they don't know what they are talking about. Of all the children I have," he continued, "Christian is the child who, from the beginning, has been the most independent. ... He wanted his own identity, and he works hard to get it."

As Christian silently wept, his father's anger returned to the fore, and he lashed out at the reporters with whom, he said, Christian "is still struggling. This is the Marlon Brando case," he said heatedly. "If [Christian] was black, if he was Mexican, or if he was poor, he wouldn't be in this courtroom. Everyone wants to get a cut of the pie, including the—" He stopped himself abruptly.

"I want to direct your attention now to the events of May the 16th," Shapiro said, "and I want you to relate to the judge when you first saw Christian that day, the day of this horrible event."

"What day is that?" Brando asked.

"The day of the death of Dag Drollet."

"Oh."

There were gasps in the courtroom. Jacques Drollet, the victim's Tahitian father, who had been staring at Brando intently, now shook his head in angry despair. Later in his testimony, after Brando had recounted the events of the evening of the shooting, Shapiro asked, "Did you see the body being taken out?" Again Brando was confused, substituting Dag's name for that of Dag's father, Jacques Drollet.

"As much as it may not be believed by Dag, Lisette [Dag's mother]—that is, I loved Dag," he said. "He was going to be the father of my grandchild, and I talked to him a lot and about taking dope and giving dope to Cheyenne. . .. That was about a week before, because I had to find out from him what kind of drugs Cheyenne took." Then he returned to the removal of Dag's body, the scene that Shapiro had prompted him to describe. "When they brought him out," he recalled, "I asked some officers to unzip the bag, and I wanted to say good-bye and admire him properly. I kissed him, told him I loved him, and that is all."

Throughout, Jacques Drollet stared back at him, and even though he, too, had tears in his eyes, there was not the slightest sign of forgiveness on his face.

The judge turned to Stephen Barshop, the prosecutor, expecting his cross-examination. But for the past several hours the prosecutor had been watching Brando carefully, calculating his own moves. He was deeply distrustful of the testimony, suspecting that all the confusions, all the deflections, all the inability to answer a direct question, were Brando at his best. "He may be acting," Barshop was overheard saying, and by the time Shapiro finished he had made up his mind. He was not going to ask for an encore or take the chance of allowing the greatest actor in the world to elicit more sympathy for himself and his son. "I have no questions," he told the judge, who then excused Brando from the stand.

Several days later, after extensive plea bargaining, Christian Brando was sentenced: 6 years for voluntary manslaughter and an additional 4 years because a gun was used in the commission of the crime, a total of 10 years in a state prison. He would be eligible for parole in about four and a half years.

Christian was hustled from the courtroom by the bailiff, and Brando followed after him through the rear exit. The area in back was caged off, with heavy barriers and chain-link fences surrounding the driveway. Hundreds of photographers and reporters were massed on the far side, shoving cameras and microphones through the bars. Brando walked out into the slight drizzle that had started to fall, his eyes hidden behind heavy wraparound sunglasses. He stepped into a Mercedes, the gate was lifted, and he was driven away.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now