Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSTATE OF THE ART

MARCH

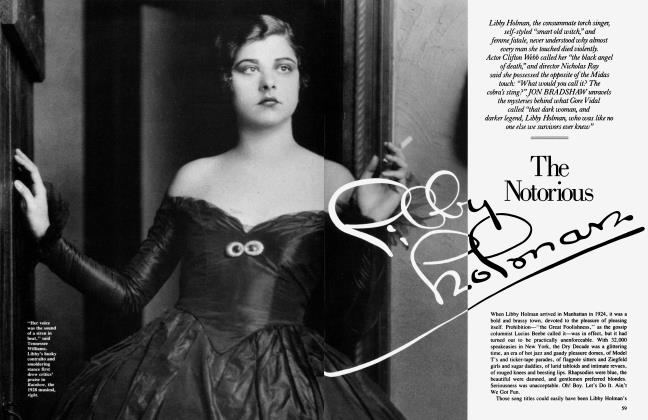

ARTS FAIR

High stepping with the Joffrey. High notes in Norfolk. High vice in Miami. High times at the flicks. High on a new writer. Art is all. All is fair.

Clemente Comes of Age

Paul Taylor

It is exactly a decade since Francesco Clemente, thirty-three this month, had his first major solo exhibitions, which opened at the galleries of Gian Enzo Sperone in Rome and Turin. A wide cross section of his recent artwork is on view in New York at the Sperone Westwater, Mary Boone, and Leo Castelli galleries this spring. With these shows, Clemente assumes the status of a significant international artist.

Like Vito Acconci, who in the art world of the seventies held a similarly exalted place, Clemente embarked on his creative life as a poet and as an artist working in the medium of books. The title of his first volume, Pierre Menard (1973), is a clue to the idiosyncratic thread that runs through his painting to date, for Menard was originally both a character and an author in a story by Jorge Luis Borges. Clemente's work resembles that of Borges—whose fiction conjures up territories in the imagination that seem more real than our world of the present—in its attempt to articulate the ways in which the imaginary and the actual intersect. In Borges's tales, the real is like a mirror of the artificial—the only point of contact is the written text. With Clemente's art, the point of contact is the canvas. His is a highly individual kind of autotelic painting.

Clemente's pictures are perverse maps of experience, charted with whatever tools are at hand. It has often been noted that he is adventurous in his use of various media—oil and watercolor, pastel and encaustic, drawing and fresco—and that he is well versed in a wide range of pictorial languages and styles, from Romantic to peasant to Eastern, although he never bothered with art school. As a Neapolitan, he says his artistic grasp reaches through sphincter after sphincter of civilization, through medieval to classical to pre-Socratic times.

His learning has been acquired in the manner more of a dilettante or tourist (he divides his time among New York, Italy, and India) than of a specialist, and his modest theorizations, which he keenly expounds, resemble the homespun philosophy of, say, Zorba the Greek, but laced with an acutely contemporary logic. Knowledge, he professes, has for too long been taught in a way that is certain to disappear—people inevitably "stop believing in one thing and start to believe in something else. The same way animals get tails, or horns, different kinds of colors.

... Knowledge... is an explanation in place of another explanation in place of another explanation, so painting is a part of this explanation."

Clemente's work, in its depiction of the multifluous circulation of energies, languages, thoughts, and excrements, is akin to Antonin Artaud's idea of a boundless body without organs. Figures consume other figures in a Rabelaisian cycle of being and becoming; orifices are pried open to reveal bodies or parts of bodies, as in his often reproduced painting of an open mouth with skulls in place of teeth. The exterior of all beings and objects is presented in relation to mirrors or from a curiously oblique, multiple point of view. Always repetitive, detailed, and eccentric, his imagery seems to represent chains of thought, but he says there is no fixed model for his art, only a wishful adaptability to change and adjustment. The pictures can perhaps therefore be said to refer to the continuum of past, present, and future in the manner of tarot cards, which are frequently cited in Clemente's work. The tarot is exemplary of an approach to knowledge which proceeds in an ever mobile fashion; as with a book, the meaning of the cards is divined by comparing the significance of the order within the pack against the order outside it. Yet Clemente's images, with their emphasis on skin, arrest for the viewer, at the material level, the giddying fluctuation between these orders. "Coming from a tradition of the resurrection of the flesh," he claims, "I want to see the body again."

Though still young, Francesco Clemente is already a vastly misunderstood artist. The most outraged critics of the new European and American art have discarded him with the same sweep of the hand they hope will dismiss all his peers and mentors, who challenge the authority of American modem and postmodernist art alike. But Clemente's insistence on multiplicity—"multiples of suggestions and possibilities"—suggests that we can consume his art with various appetites, that no one system of knowledge, and certainly no ideology, can be master.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now