Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHot Type

BOOKS

After nearly a decade, Philip Roth now brings to a close his trilogy about the life and times of Nathan Zuckerman, the quintessential Jewish-American novelist. The three previous Zuckerman novels {The Ghost Writer, Zuckerman Unbound, and The Anatomy Lesson) have just been re-bound, so to speak, with a new epilogue, in Zuckerman Bound (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). There is a certain, well, chutzpah in republishing this work so quickly and in such a grand format—but chutzpah has played an important part in Roth's career ever since Goodbye, Columbus (1959), when he satirized suburban Jewish life with merciless detachment.

Roth later attracted a huge, if antagonistic, audience with Portnoy's Complaint, his portrait of the Nice Jewish Boy as masturbator. In retrospect, the work remains a comic masterpiece—the ultimate post-Freudian novel—but it sent Roth into an artistic tailspin. Wealth and fame, the twin horses of the all-American chariot of the soul, dragged Roth down. He churned his way through several flawed novels until hitting upon Nathan Zuckerman, his fictional alter ego. Though Roth would doubtless say it isn't so, Zuckerman Bound is something of an autobiography; what isn't factually true is nonetheless emotionally true.

And the trilogy is dazzlingly good. In The Ghost Writer, a miniature hall of mirrors that imitates, at least in form, a Henry James story ("The Lesson of the Master"), Roth paints an exquisite portrait of the artist as a young man. Zuckerman Unbound is less intricate but funnier, the chronicle of how success ruined Nathan Zuckerman's sleep. With The Anatomy Lesson, Roth sees his hero through to his wit's end, in a hospital, his tongue swollen to a point where the man who lives by words can no longer speak them. The new epilogue, a Zuckerman diary set in Prague, recapitulates many of the themes laid out in the earlier novels and brings the trilogy to an affecting conclusion. Roth is clearly one of our best writers, and this is his finest moment.

Jay Parini

In her novel Love Always (Random House), Ann Beattie has finally transferred out of the School of Malaise. Gone are the enervated latter-day hippies and aimless story lines. Beattie, like her character Lucy Spenser, continues to exhibit "a morbid fascination with being facile," but in her latest book she has latched onto the perfect subject both for her talents and for the 1980s—the entertainment industry, which by definition doesn't have any depths to plumb. Lucy Spenser seems to speak for Ann Beattie when she says that "since you [can] get away with anything, it [is] necessary to start your own fun." And Love Always is fun. It is also a spunky send-up of the trends and media hype we embrace and those who create them.

Hildon, a preppy-ish kind of guy in his late thirties, has hit on success by founding the satiric, Vermont-based magazine Country Daze, "the hit of tout New York." Hildon is married to unbalanced Maureen, but in love with Lucy, his oldest friend and the voice behind Country Daze's Cindi Coeur, a wickedly witty Miss Lonelyhearts. The main action, however, revolves around Nicole Nelson, Lucy's niece and the star of the soap opera Passionate Intensity. (See Yeats's "The Second Coming" for the reference.)

As always in Beattie's work, an abundance of disposable characters and scenes dilutes the story's pacing and power. And, of course, there remains the gratuitous littering of names from current events that has become a Beattie trademark. Despite these flaws, she has used her considerable intelligence, sharp eye, and arch humor to rip into media madness and the so-called glamour professions. Best of all, she gets seduced by her own creation. Closing in on Lucy, Nicole, and a family tragedy, the last third of Love Always develops into a moving exploration of love, responsibility, and family ties, wonderfully evoked and quite perfect for a TV Movie of the Week.

Cheri Fein

The subtitle for this collection of articles from the influential journal Cahiers du Cinema could be "group portrait of the artists as young critics," or, as many of their critical targets would have said, " . . .as young punks." For this volume, The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave (Harvard), the first in a projected series of four in English translation, is dominated by the fiercely polemical writings of the very young Turks who were soon to become famous as the "New Wave" directors. Founded in 1951 by Andre Bazin and others, Cahiers gave Truffaut, Godard, Rivette, Chabrol, and Rohmer their first opportunities to test the theories and prejudices that later, through their films, transformed the entire French movie industry—and, indeed, profoundly affected the way movies were made and viewed throughout the world.

The critical cornerstone of Cahiers in the fifties was, of course, the famous (or notorious) politique des auteurs, first formulated by Truffaut. He and his colleagues argued passionately (with bad manners and sometimes worse grammar) that the best films expressed the personality of a single man, the director, and that the best of these film auteurs deserved to be ranked with the best novelists, poets, and painters of their age. That these ideas sound commonplace today signals the extent to which the battle in behalf of the film auteur has been won.

The fiercest and most significant fight in the pages of Cahiers during this period was not, as has sometimes been supposed, over the commercial American cinema, but rather over the future of the French cinema. Truffaut and his colleagues saw the same qualities in Hollywood films of the forties and fifties that they admired in the neorealist films of Rossellini and early films of Renoir. But these qualities, they felt, were pitifully lacking in the established French cinema of their day: formal experimentation, an attention to personal concerns, a humanist worldview, and, perhaps most important, a direct engagement with contemporary society. And these are the precise qualities that the New Wave returned to French films with a vengeance.

In these early essays, the budding French auteurs painted portraits of their American and Italian idols that became, in time, self-portraits.—Steven Simmons

Should you come across a copy of Gossip (Knopf) and think you've found this summer's beach read, be forewarned: it's not written by a tabloid tipster, and you'll search in vain for references to Lynn Wyatt, Monaco, or the von Billows. Gossip is the work of Yale professor Patricia Meyer Spacks, and is anything but lightweight. The author is obviously a woman with a mission—to have gossip taken seriously in literature as well as in life.

Spacks set about her herculean (or was it Sisyphean?) task by tracing gossip's career through the pages of English and American letters, from Chaucer to Toni Morrison. Exhaustively researched and copiously annotated, Gossip illuminates numerous examples of its subject at work, relentlessly arguing that genuine gossip fosters intimacy between gossipers and thus performs a most useful social function.

Of course, not all gossip is highminded, and Spacks is quick to separate "serious" gossip from the garden variety, exemplified, in her view, by People magazine. Dismissing it and its ilk as mere "parodies" of gossip (because they foster only the illusion of intimacy), she inveighs that "such texts cast lurid light on gossip as a phenomenon." Indeed, she continues, "I would find it in many ways more convenient for my argument simply to ignore People and its shady relatives."

Would that we could, Professor Spacks, but in gossip, as in anything else, one must take the seamy along with the sublime. To her credit, however, the author does consider both. Gossip may be one of the more tedious reads of the season, but the voyage it charts through the plots of Anthony Trollope, Jane Austen, George Eliot, and the like is worth the ride. It may not be what you expected, but read Gossip anyway. Just take something else to the beach.

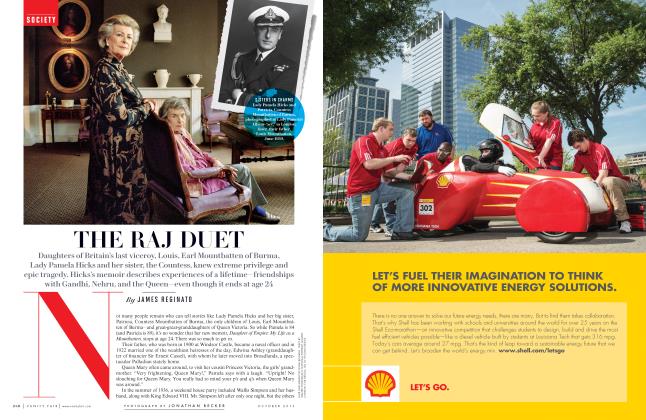

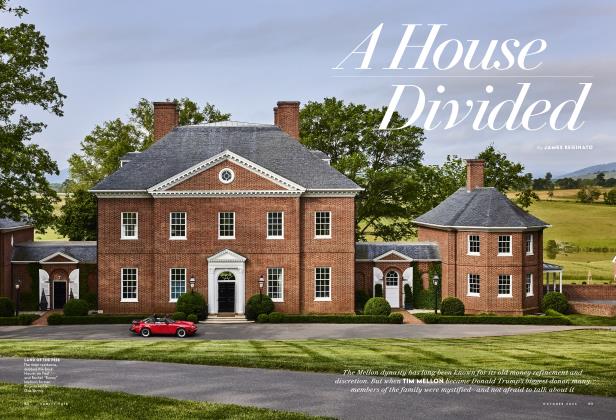

James Reginato

With the recent, acclaimed publication of his memoir The Periodic Table, Italian writer Primo Levi proved himself not only a chemist (which he is by profession) but also an alchemist, turning the base materials of his trade into literary gold. In If Not Now, When? (Summit), he proves himself as deft with fiction as with autobiography.

''Nobody has ever heard of Jewish partisans," says Levi's Russian lieutenant, but indeed they did exist. In fact, Levi's adventure-filled chronicle follows just such a group across wartom Russia, Poland, and Germany as they snipe at and sabotage the German troops—arguing, laughing, loving, and betraying one another. Under the surface, Levi probes the much explored but still unexhausted theme of Jewish resistance during the war, as the ragtag group of strays and stragglers get their first taste of freedom and dignity, as Jews fighting without fear.

Levi depicts the circumstances which could turn a doubtful watch mender, Mendel Nachmanovich, into a man of action. Or Gedaleh, the band's lighthearted leader, who can't part with his violin, into a man who won't part with his gun. Death is inevitable in any war tale, but Levi's book is more concerned with life, and how to live it with dignity and decency in a world bereft of both.

Sarah Gold

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now