Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

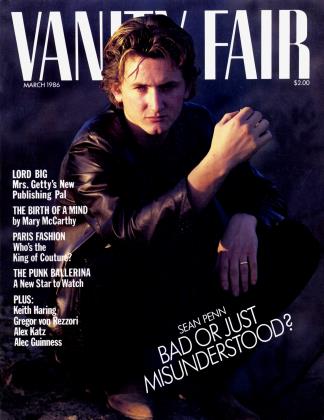

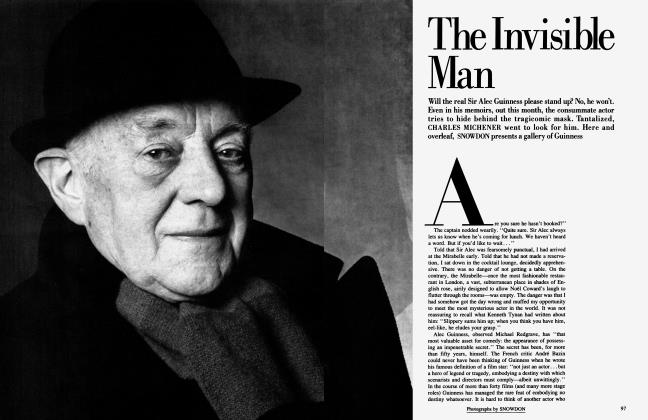

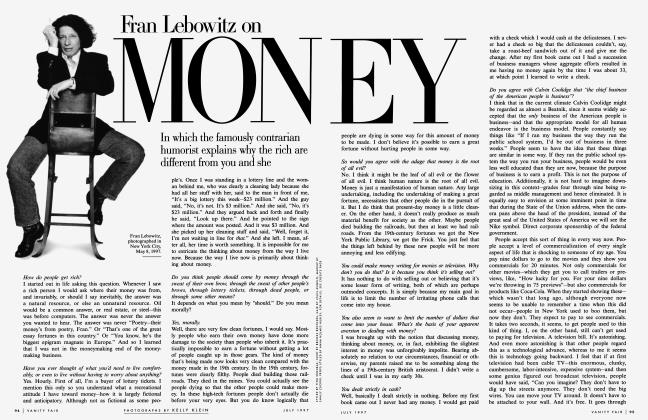

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThere has always been a king, or queen, of Paris fashion. Poiret, Chanel, Balenciaga—each in turn ruled a couture court. Today, it's more like the Wars of the Roses, with continually jousting princelings. JAVIER ARROYUELO examines the claims of three of them

March 1986 Javier ArroyueloThere has always been a king, or queen, of Paris fashion. Poiret, Chanel, Balenciaga—each in turn ruled a couture court. Today, it's more like the Wars of the Roses, with continually jousting princelings. JAVIER ARROYUELO examines the claims of three of them

March 1986 Javier ArroyueloWhen covering the fashion scene in Paris, one is sometimes tempted to borrow from the vocabulary of war historians. Attacks and counteroffensives, betrayals and revenge, convulsions and revolutions can be woven into a tortuous, impassioned plot, a living tapestry reminiscent of the tumult of feudal France.

But one can also tell the story in the abridged manner of TV Guide. Egos collide, fortunes are made, pills are swallowed, and nerves break down—just like in one's favorite prime-time high-trash soap. Glamour and champagne overflow—both exactly chilled. Huge parties are given and private planes boarded with unreasonable, alarming almost, frequency. Joan Collins shows up. Catherine Deneuve passes by. Of course nobody looks poor.

The passions intensify four times a year, twice for haute couture and twice for ready-to-wear, when the Paris fashion world, unionized though not necessarily united, reveals its latest concoctions during a weeklong marathon known as la semaine des collections. The events are attended by an inflammable crowd—more than two thousand journalists, delegations of buyers and store representatives, and a few, but highly visible, cliques of assorted celebrities, rich ladies, fashion addicts, and fashion freaks.

Late this month, under three tents erected in the Tuileries Gardens, the créateurs de mode will unfurl the winter ready-to-wear collections. It will be fashion mumbo-jumbo time again— fashion talk and fashion lunches and teas and cocktails and dinners and parties for which one puts on one's fashion face (and as many different costumes as is humanly possible). Paris will be swept by a delightful lunacy. Between shows sumptuous models in full runway makeup will stroll under the arcades of the Rue de Rivoli. Weary fashion editors armed with notebooks and pens will hurl themselves into the hectic schedule (over fifty presentations) and get their seasonal OD. For a while the real world and its real wars, Gorbachev and the nuclear menace, will disappear from the collective consciousness, to be replaced by the heroes of the fashion saga.

Ever since Louis XIV, short and balding and majestically conceited, made towering, elaborate wigs and high scarlet-heeled shoes de rigueur for his courtiers, fashion in France has thrived under one-man rule. Paul Poiret, Coco Chanel, Christian Dior, and Balenciaga reigned, each in their own time, over a mock Versailles concerned exclusively with frivolity and froufrou, and dependent on tight, recognizable hierarchies. During the sixties, Pierre Cardin and, more briefly, André Courrèges enjoyed their respective moments. But in its unending quest for the newest and the most salable, the fashion monster machine gulped down every King and Queen.

The latest Roi Soleil, sanctioned by the press, ratified by the industry, copied by his colleagues, and idolized by the ladies who shop, is Yves Saint Laurent. He has repeatedly created fashion drama during the last decade, making it his very own sparkling era. But the exclusivity of his reign seems now to be threatened. In fact, the role of the absolute monarch itself seems to be a thing of the past, no longer an archetype but a faded clichd. Those who in earlier eras would have been regarded as crown princes have gone deliberately democratic, pretending not to the crown but to the idea that has no crown.

"There is no major figure, no determining style, no signature prevailing over the others. There is no first place anymore,'' says Karl Lagerfeld, the protean talent behind Chanel and Fendi and his own KL line. "Thank God, the era of Monsieur Dior and his Y line is definitely over." Lagerfeld, a polished Dark Prince whose public image is a studied version of the grand sophisticate, has been a major designing force for the past fifteen years. Next to him among princes stands only Azzedine Alaïa, a diminutive conquistador (naughty Parisians call him le designer de poche) who burst upon the fashion landscape a few seasons ago. Paris shouts out Alaïa's name, and that dernier cri, you may have noticed, is already echoed at every comer boutique.

Lagerfeld and Alai'a, the Dark Prince and the Conquistador, both encourage the fashion-conscious to mix and remix looks in order to achieve a personal style. Alai'a likes to link his work to that of such disparate designers as Rei Kawakubo (of Comme des Gargons), Yohji Yamamoto (another Japanese purist), Jean-Paul Gaultier (an enfant terrible), and Thierry Mugler (an enfant terrific). This is no hypocritical invention of a phony fraternity but a tactical and realistic appraisal of the many directions fashion has taken. Saint Laurent, on the other hand, perhaps in spite of himself, has incarnated—or at least conveyed—the tradition of uniqueness.

The mystique of Yves Saint Laurent has endured for twenty-five years, and by now he has achieved fashion sanctity. Today only the profane, or the downright heretical, would question Saint Yves's stature. You don't dismiss Notre Dame cathedral—even if monuments bore you to tears.

Everything about the House of Saint Laurent is redolent of religion. Sweet incense is burned and blind faith required. (Actually, the faithful believe so blindly in His perfect taste that their fanaticism passes unnoticed.) Classicism and simplicity are the basic commandments, but in his obstinate pursuit of purity, Saint Yves has fallen upon austerity. Gone are the extravagantly brilliant days when he conjured up the Ballets Russes in a vertiginous, breathtaking parade of dramatic, lavishly colored taffeta ball dresses, with skirts in full bloom. The genius who was once inspired by the slapdash looks of the street and restyled them, in a flash, into high urban chic appears now lost in a drawing-room reverie—perhaps in a tête-à-tête with the improbable ghost of the Duchesse de Guermantes.

Azzedines clothes hug, wrap, shape, and exalt the body. He has reinvented the notion of curves— and he even invents curves where there are none.

Like an ayatollah, Saint Laurent appears in public only for official occasions. There is no chance of catching him at such hot fashion spots as Les Bains, the rackety rendezvous for fashion veterans and younger things. He seeks seclusion and finds it at his Parisian house among Goyas, Picassos, Delacroix, and Matisses, or in his Marrakesh gardens, or at Chateau Gabriel, his estate in Normandy, where each bedroom is dedicated to a different character from Proust's "Remembrance of Things Past." Concentric circles of middle-aged priestesses—publicists and assistants acting as confidantes—further insulate him from the ordinariness of the world, that place where trendy women might be found wearing other designers' dresses.

Saint Yves inhabits extremely rarefied heights indeed. In an interview with Le Monde two years ago, he said: "My job takes up all my time and energy. Creating is a harrowing business. I work in a state of anguish all year. I shut myself up, don't go out. It's a hard life, which is why I understand Proust so well; I have such an admiration for what he has written about the agony of creation." He sounds light-years away from the gifted boy whom Karl Lagerfeld, a close friend in their youth, describes as "cheerful, very funny, très drôle."

Saint Yves was born in colonial Algeria to a middle-class French family. In the Le Monde interview he recalled that "on one side there was the cheerfulness of our home and the world I created for myself with my sketches, sets, costumes and my theater. On the other, there were the trials of a Catholic school. . . where my fellow pupils mocked, terrorized and bullied me.... In my mind, I would tell them: 'I'm going to get my revenge; you'll be nothing, I'll be everything.' " In 1954, when he was eighteen, he shared first prize in a trade association's design contest; Lagerfeld won for the best coat and Saint Laurent for best dress. He became the precocious right-hand assistant to Christian Dior, then basking in full New Look glory. When Dior suddenly died, Saint Laurent took his place as the house's chief designer. In 1958, when he was barely twenty-two years old, he showed his now historic "trapeze" collection, the first in a long series of smashing fashion hits.

The arts proved a rich source of inspiration for Saint Laurent's nervous, vehement sensibility. Almost defiantly, he turned his haute couture collections into vibrant, highly emotional homages to Picasso and Matisse, Cocteau, Shakespeare. He lifted haute couture—the main purpose of which is the merely decorative—to unexpected heights. Yet he never ceased to contribute essential elements to the basic wardrobe of the contemporary woman. The tunic, the daytime pantsuit, the smoking du soir—to mention only a few—acquired, thanks to him, the status of classics. But it is in the use of color that Saint Yves revealed an undisputed artistry. He opened our eyes to an exquisite, audacious palette.

In 1962 Saint Laurent founded his own couture house in partnership with his companion, Pierre Bergé, a bossy figure of tempestuous moods who has ever since fueled the flame of the Church of Saint Yves with Gallic ardor and unfaltering tenacity. He serves on the front lines of the fashion battlefield, turning back enemy troops with gusto. It was typical of Bergé to dismiss the foreign designers who show their collections in Paris with the remark that "you don't bring coals to Newcastle."

Bergé is usually credited for the impressive business accomplishments of the Saint Laurent label, although many close collaborators insist that Saint Yves himself is commercially acute. In spite of the agonies of creation, he pays great attention to even the pettiest details of packaging. In 1966 he and Berge launched the Rive Gauche ready-to-wear line, and now the Saint Laurent empire includes nearly two hundred boutiques worldwide plus a plethora of "designer" products, from cosmetics to cigarettes.

Saint Yves and his Pontifex Maximus have piled up honors as well as cash. At an intimate ceremony held in the Élysée Palace last year, with Saint Laurent's chums Françoise Sagan and Paloma Picasso looking on, Mitterrand graced him with the Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur. Bergé has astutely secured for himself a key role in fashion politics by getting elected president of the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter des Couturiers et des Créateurs de Mode, a rather baroque institution, as the name indicates. President Berg6 is at the moment deeply involved in the birth of a Musée des Arts de la Mode, to be housed (where else?) in the northwest wing of the Louvre. Predictably, its second exhibition will be devoted to Saint Yves's oeuvre. This comes three years after the major retrospective staged by Diana Vreeland at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which was also shown in Beijing.

After so much pomp and circumstance, the affair of mere clothes may strike Saint Yves as quite anticlimactic. A rumor heard a few seasons back in Paris, now re-emerging, holds that the House of Saint Laurent is about to set up a team of young designers who would carry on with the Rive Gauche ready-to-wear line, while Saint Yves would consecrate himself to the hallowed high-couture fantasies at which he excels. Such a move would automatically take him away from the fashion race and put him on a splendidly solitary track of his own. Rather than come round again and again to the same nononsense basics, he could fulfill his dream of the theater and its illusions, creating dresses for the fabulous creatures that haunt his imaginary stage.

It would be a wise, dignified decision. Perceptive as he is, Saint Yves may have guessed that his emblematic woman has begun to show her age. An ice cube in black velvet and an iceberg in sable, she and her master are locked together in a tableau of frozen elegance.

Karl Lagerfeld has no emblematic woman to worry about. More chameleon than Pygmalion, he designs three distinct looks: the updated Chanel wardrobe, the Fendi fur extravaganzas, and the witty and chic KL collection. He is, at forty-eight, probably the only designer who combines highfashion savoir faire with an ability to adapt to the trends in ready-to-wear. He started as Pierre Balmain's studio assistant, was later chief designer of the House of Patou, and in 1964 entered the field of ready-to-wear, designing for Chloé, a small firm where he kept a low profile while driving it single-handedly to the top of the market.

At Chloé he perfected ready-to-wear de luxe. But rows with his Chloé partners plagued his rise, and after several rounds of punching he moved on. The company is, to this day, afflicted with creative numbness, while the avenging Dark Prince proceeds on his speedy way up, a fashion Rocky eager for yet another sequel.

The Dark Prince lives up to his title, and you cannot avoid noticing it. The glossy pages have repeatedly exposed us to Grand Champ, his Brittany castle with its manicured gardens, his hip apartment in a Monte Carlo high rise filled with Memphis modernissima, his house in Rome decorated to look like the interiors in late-eighteenth-century Danish paintings, and his Paris apartment, a fastidiously exact triumph of eighteenth - century French taste that occupies one wing of an hôtel particulier on the Rue de l'Université. You certainly cannot have missed the master of these places, a stocky man who sports tinted glasses, a ponytail—plus a fan on some occasions—and impeccable three-piece suits, tailor-made in Milan, cela va sans dire.

The German-born Dark Prince is the son of a Swedish businessman who made a fortune with Gloria, a brand of condensed milk. The Prince grew up in a manor in northern Germany's countryside, a golden, though lone, boy. One imagines the child, an avid reader, putting on a pout as he leafed through magazines and books—for the pout as well as the leafing has remained. "I don't want to be 'cultivated'—that word is too pretentious—but extremely well informed," he says. "My curiosity, my voyeurism are absolutely frightening."

"There is no major figure, no determining style. There is no first place anymore," says Karl Lagerfeld.

Behind the grand seigneur—the collector of splendid houses, antique furniture, and paintings—lurks a skilled fashion professional with the alertness of a shark. Karl Lagerfeld is the man who broke the spell of the Chanel mummy. He likes to picture himself as an emergency doctor who was called to the rescue of the ailing house on the Rue Cambon and made business increase, so he claims, over 300 percent in just three years. He rejuvenated the famous Chanel suit, the exhausted uniform of the grandes bourgeoises, through repeated shock treatments (he brought leather and even denim to the kingdom of gold-trimmed tweed) and intensive corrective surgery (wider shoulders, roomier jackets, a sharper silhouette that includes even pants). Saint Yves—an heir to the Chanel aesthetic—had already prescribed quite the same medicine to quite the same patient, but in the claustrophobic Chanel mausoleum such audacities had been forbidden. In any case, Chanel's Chanel now looks modem and refreshing, and women have adopted it again as a basic classic.

This fashion feat brought to the Dark Prince increased notoriety and respect. Yet there has been trouble within. The fashion press has been full of speculation about internal disputes, conflicts between Lagerfeld and die Chanel management. Lagerfeld has his own reasons for being dissatisfied with Chanel. ''They take themselves very seriously there. Ça m'assomme—that's too boring. Of course, it amused me to put Chanel back on the map. I enjoyed it. I felt like an actor performing a new role. But I'm not going to go on forever with four pockets, two gold buttons, and a gold chain."

Lagerfeld speaks mischievously about his couture stint. ''I came in, a wolf among the lambs," he says. "And now I'll very probably leave—out of boredom. The mood of the 'salon de couture' doesn't suit me." He puts on a phony accent, mimicking an unctuous couturier: " 'Has Madam chosen? Is Madam happy? We'll give you 10 percent off... ' Some of my colleagues do that sort of thing, which seems to me the height of mediocrity. " And he adds, "Then there is a solemn side to haute couture. All those honors and homages. .. .It reminds me of the pompier painters, who were so revered by the bourgeoisie and the state in the late nineteenth century while the Impressionists were being ignored. Naturally, one doesn't want to be a pompier, no?" But whichever school he chooses and whether he stays at Chanel, with more power, or prefers to expand the KL venture, one thing is certain: the Dark Prince is plotting a bright future for himself.

Lagerfeld seems never to switch off. He throws out quotations from the classics, funny anecdotes, and nasty remarks in submachine-gun tempo. In a typical week, back from New York, where his sportswear line was presented, he stops in Paris for less than fortyeight hours, flies to London for three days, returns to Paris for an afternoon with the press, and rushes the same evening to Monte Carlo—just to sleep, though, for he is in Rome the day after. "Change, perpetual change, that's what keeps me going," he explains, seated under a portrait of Mile, de Charolais, among the eighteenth-century splendors of what he calls his workroom. "I don't live to build a career. I just do for the pleasure of doing. Pretentiousness runs high in this business. One is supposed to suffer. The slightest ease, any dexterity, are seen as a symptom of superficiality. Well, I love superficial and artificial things. This is just dressmaking, after all, not the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel... Actually, fashion is the apotheosis of flimflam. You can make it work with no real knowledge ... Many people in fashion think that instead of stylists they should have been... " and as he pauses for effect, he places one hand on his forehead in a silent-movie gesture, then whispers, ".. .Architects.. .Architects! They don't seem to even suspect that one has to study, I mean really study, in order to become an architect. If a house falls apart, people get killed. If a dress doesn't fit, you just don't put it on. There's quite a difference, no? I don't understand these people. They should realize how incredibly lucky we are. We can put our names on a bottle of perfume without knowing a thing about perfume and we make fortunes with it. But no, there they are: suffering."

For a long time, the Paris fashion houses maintained the prestigious couture sides of their operations to enhance the appeal of such by-products as perfumes and cosmetics. Then, as a consequence of the erratic economic policy of the socialist government, the French franc plummeted and that mythical figure, the Rich American Lady, reappeared and multiplied. Quite unexpectedly, couture was financially sound again. But this bonanza could fade just as abruptly as it came.

Couture as a métier requires exactness of execution, skilled artisans, endless hours of work. Extravagant, aberrant prices for the product result. Couture prices start at $5,000—for a simple, unadorned day ensemble—and easily skyrocket to six figures when outlandish ball gowns and intricate embroidery enter the picture.

Then there is the question of the aesthetic survival of haute couture. There are only a few designers, like Saint Yves and Hubert de Givenchy, who continue to reiterate its aristocratic principles. Ready-to-wear, on the other hand, bristles with creative talent and is, from the business point of view, perfectly attuned to the realities of the day. Just as haute couture responded to the needs of the ostentatious rich, ready-towear addresses itself to the unequivocally prosperous. Paris is overwhelmingly middle-class, and ready-to-wear has always conformed to the juste-milieu, absorbing in time even the most outrageous fashion follies—exemplified these days by Jean-Paul Gaultier.

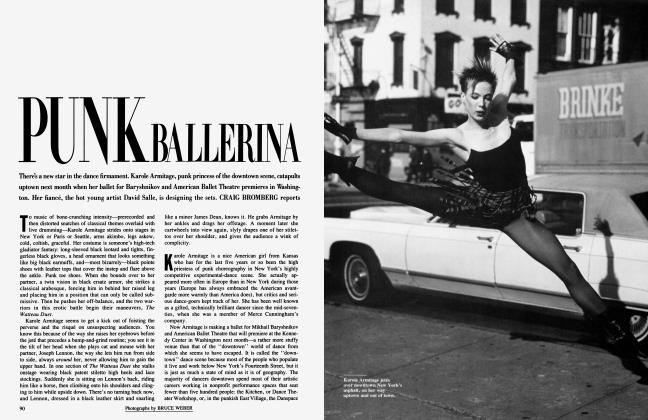

Now, as usual, it is from the street that the strongest message emanates. From the energetic "Don't walk, run!" streets of fitness-conscious America. And it is once again from Paris, fashion's grand laboratory, that the reply comes, brought by Azzedine Alaia, the man whose clothes fit fitness and build the body.

To follow Saint Yves, a glorious stroke, a masterly touch, are required, and Azzedine seems to be the only contender gifted enough to achieve such a thing. Tunisian-born, Paris-reborn, he is a man of singularities. His size strikes you first, for he is a tiny sprite, and then his garb: a black Chinese outfit complete with tiny shoes. His only accessory is a saddlebag in which he carries his pet Yorkshire, Patapouff. If understated cuteness can be carried off, Azzedine has done it.

He conducts his career in the most unconventional manner. No ads, no tinsel shows, no luxurious private life. About fifty—his age is one of the many secrets he manages to withhold from the press—he is hitting the limelight late. For two decades he designed for a special clientele, far from the hurly-burly of fashion, in the privacy of a small apartment doubling as atelier and fitting room. Azzedine is almost alone among his peers in the mastery of every technical aspect of the intricate process of dressmaking. He drapes, cuts, and sews to perfection. Like the legendary, and still active, Madame Gris, Azzedine is a superb craftsman in the classic manner. But his finesse would remain only a minor accomplishment without the fecundity of his imagination.

A farmer's son, Azzedine grew up with his grandmother, who fed him on Arabian tales of magic and romance and eventually helped him to enter the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Tunis, where he studied sculpture. The effect of the grandmother's tales is visible today in his amorous, bewitched vision of women, while the sculptor's eye and touch are revealed in the flawless structure of his clothes. They hug, wrap, shape, and exalt the body. Azzedine has reinvented the notion of curves—and he even invents curves where there are none.

The prudish regard Azzedine's clothes as excessively erotic, when in fact they are simply sexy in an alluring, natural way. His rigor and refinement temper even his more risqu6 creations. He provoked an uproar with a swimsuit cut high over the hips, a true homage to the derriere. Azzedine couldn't see the reason for the fuss. He had simply revealed the exquisitely bare buttocks of his models to be "like a pair of apples, ripe and gleaming in the sun.''

Last year, le petit Azzedine moved from the crammed apartment on the Rue de Bellechasse, where he had slept on a mattress under a desk, to grander headquarters, more in keeping with his eminent position. He operates now from a five-story house in the Marais district, an old hotel transformed by interior designer Andr6e Putman, one of his biggest fans, into a minimalist jewel. The kitchen is in the basement, the boutique on the first floor, and up the narrow staircase you find, successively, a reception room, then Azzedine's studio, then his living quarters, and, in the spacious attic, the studio of his friend Christophe von Weyhe, a German painter. The place, needless to say, is hardly reminiscent of a couture house— or of an ordinary house, for that matter. It is the frenzied set of a lively fashion comedy. Pert young assistants run up and down the stairs, dogs and models bark and trill, friends drop by. At lunchtime everyone joins Azzedine at a big marble table in the kitchen, where the gathering includes shopgirls from upstairs and seamstresses from the atelier around the comer.

One afternoon last summer, Regine, the godmother of international nightlife, was trying on (in eighty-degree heat) Azzedine's celebrated reversible mink jacket, while the telephone rang nonstop. Putting on a mock voice—highpitched French with a strong American accent—Azzedine himself answered some of the calls. Through her secretary, Elizabeth Taylor was ordering three sweaters. Paloma Picasso, one of the most prominent Alala addicts, was expected for a fitting. Azzedine's list of clients includes, besides practically every young French movie star, Tina Turner, Raquel Welch, Grace Jones, Iman, and the créme of models.

Azzedine has enraptured the press and set the street on fire. His original look is being shamelessly reproduced to the last seam by some American designers—and with dangerous unconsciousness by top Parisian names. Next summer, when girls whip by in their tight new Alai'a denim minis and sculptured, zipped denim blousons, men will gasp for air and the fashion industry will peer closely at what the Conquistador has made of what everyone else thought was a worn-out theme.

Azzedine's unpredicted blitz has reinjected aggressiveness and vitality into the Paris scene. But his ensuing conquest has yet to be confirmed by the U.S.A., a crucial market where, far from the subtleties and intrigues of the court of fashion, Saint Yves remains His Majesty. Last fall video-maker Jean-Paul Goude staged, with Azzedine's blessing, a blockbuster parade of his clothes at the Palladium. New York's glitterati attended en masse. The two-hour-long show, spiced with ethnic references and set on a gigantic staircase, left them blowing hot and cold. Although these New Yorkers are professional sophisticates and blas6, they are not used to the boisterous runway antics much in vogue in Paris. But neither is Azzedine, for that matter. In

fact, back home Azzedine refuses to comply with the prevailing razzle-dazzle. His collections are shown in a small bare salon far from the brouhaha of the Tuileries Gardens. He has ruled out music and special effects. Calculated modesty restrains Azzedine even from taking his bows. Unlike his colleagues, he has never stepped down the runway amid loud cheers and throbbing paparazzi flashes. Those details notwithstanding, Azzedine possesses all the signs and symptoms of success, and he has taken his place among pop royalty.

For pop royalty is what fashion designers have become, the newest attraction in the media-hype circus. The craft, once revered only by the elite, has entered the stage of mass adulation previously reserved for movies, sports, and rock 'n' roll. Fashion no longer lives for fashion's sake alone. More realistically, clothes are now fodder, produced to be consumed off the rack. At a time when Coca-Cola is Classic and pizza is chic, fashion has had to transcend its old notions of classic and chic. So fashion has gone global, and its traditional wars,

with short versus long, spare opposed to luxurious, nouveau poor fighting old rich, seem somehow obsolete. Hot trends and fresh ideas, instant fads and ephemeral rages, keep popping up in Milan, Tokyo, London, and, yes, even New York. As a consequence, the central position that Paris once occupied on the fashion map as the Holy See of the rag trade, the charmed landscape where Beauty and the Bitch go hand in hand, has been diminished. Designers now fly worldwide, with jet-lag-proof stamina, glamorous pilgrims of chic with Paris in their satchels. They have no time for nostalgia, no reason to complain that Paris was yesterday, since the spirit of Paris fashion is present everywhere.

One is tempted at this point to conclude with a futuristic vision, à la Marshall McLuhan, of a big bang. For there is no need even for a summit meeting among fashion's powers now. The bomb has already softly and quietly been exploded. It is fashion's Day After. Everybody's got his piece of the cake, and, big bang notwithstanding, they all look unruffled—and perfectly groomed, of course.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now