Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTango—Mania

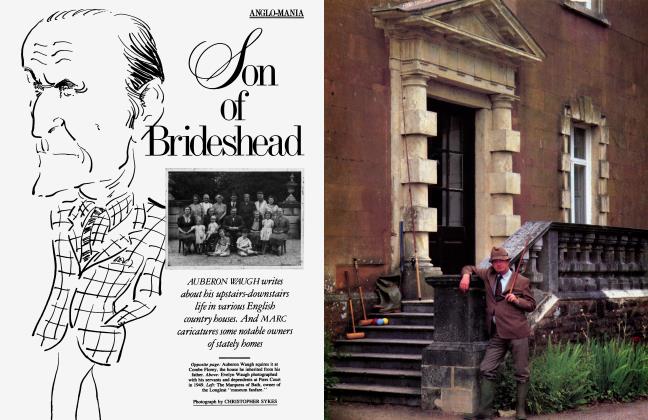

The tempestuous Tango Argentino troupe, which wowed New York during its lightning visit last summer, hits Broadway this month. JAVIER ARROYUELO and RAFAEL LOPEZ-SANCHEZ tell the sensuous story of el tango, from its low-life origins to its high-society success

This is how we remember Buenos Aires, in nineteensixty-something: oppressive jasmines, invisible in the dark, and the faint sound of a tango in the distance. It is a summer night, somewhere a suburban radio is playing. We were teenagers then, helplessly devoted to rock V roll; yet when memory rewinds its sound track it is the melody of a tango—"Vida mia, vida mia"—that comes out, sweet and soft and inebriating.

In those days we thought of tango as a relic, worn but cherished, a stack of touching black-and-white postcards turning to sepia. It seemed valuable (older people treasured it) yet vulnerable (only older people treasured it). It was a Norma Desmond kind of thing, both fascinating and pathetic, glorious and tacky, still alive in spite of its many deaths. The aura—it possessed an aura—would flicker and we could not determine whether he (in Argentina the tango is a he: el tango) was a wise old man or just an aged roue. Or both. Or something else.

Then, like in a tango, we left home, flew far away, grew up, and grew homesick. Our turn came to keep up the memory of tango. And one day, we were suddenly gratified with a fantasy present, a show, Tango Argentino, sleek, exalted, and soulstirring. The terse title masked a jewel.

Two Argentinean set costume designers, Claudio Segovia and Hector Orezzoli, created Tango Argentino. Theirs is a Cinderella sort of tale, the kind of story that feeds the mythology of show business, although it took them a long ten years of patience and tenacity to turn their improbable venture into a Broadway property. They had been living bi-continentally, in both Buenos Aires and Paris, designing operas and plays and putting on their own musical productions, when they got the idea of making a show with the tango singers and dancers who perform in Buenos Aires' nightclubs and on TV shows. But adequate financial backing was not forthcoming in Argentina—which would have been the show's natural birthplace—and the project was put on a back burner.

A man and a woman, trapped in a felted embrace, unravel with their bodies the figures of a ritual

Then in 1983 Segovia and Orezzoli decided to try Paris. When it comes to exotic cultural products, Parisians like to think of themselves as broad-minded. (Parisians encounter exoticism as soon as they cross the city gates.) In any case, Tango Argentino promised to be tangy enough for the Festival d'Automne's international menu, and the show got its first booking. The festival would provide—besides its prestige—a suitable promotion, minimum wages, small hotels. But no airfare. The thirtythree members of the company were flown in from Buenos Aires by the Argentinean air force in a big clunky plane that was also transporting a defective Exocet missile back to Paris for repair.

Many of the singers and dancers were discovering Paris for the very first time. They felt like a zillion pesos. Performances were to take place at the Theatre du Chatelet, a grand house, in both size—over two thousand seats—and history: in 1909 Diaghilev's Ballets Russes made its debut there. They sensed they could have a glamorous run, although barely two hundred tickets had been sold in advance. Resorting to an old gaucho tradition, friendship, Segovia and Orezzoli and a handful of fellow Argentineans summoned potential tango lovers to the opening night. It became a thrilling, enrapturing, memorable event. The day after, word was passed all over town. Parisian critics raved and the house was solidly sold out.

The triumph was to be confirmed throughout the Continent. The uproar even reached North American impresarios. Tango Argentino became a seasoned traveler, although there was one stop that Segovia and Orezzoli preferred to skip. They dreaded—who wouldn't?— that ultimate test, New York. But then, on very short notice, they learned that they had lost their theater in Washington, D.C., and were suddenly being booked into Manhattan's City Center at the end of June. Both organizers took a stiff drink and a tranquilizer.

Their fears were uncalled-for. New York responded just as Paris had. Tango Argentino glided silently into town, and by the second night of its six-day run it had become the hottest ticket in the city. Every performance was filled with cheering crowds of tango lovers. Jacqueline Onassis was there on the second night. Martha Graham, the doyenne of American dance, came twice. Gloria Vanderbilt, Mica Ertegun, the fashion press, the literati. Everyone loved the Argentineans, and everyone agreed they had never really seen the tango before.

Tango Argentino follows the chronology of the history of the tango, each sequence illustrating a special moment. Appropriately, the curtain rises on "Quejas de Bandoneon," a highly emotional orchestral piece and one of the purest examples of the distinctive tango beat. (The bandoneon, an accordion-like instrument, is central to the plaintive sound of the tango.) Pungent and melancholy, this ''Bandoneon Lament" establishes, right from its first chords, the atmosphere that prevails throughout the show. As it unfolds, you are taken to Buenos Aires. For, as Jorge Luis Borges noted, ''it might be said that without Buenos Aires evenings and nights no tango can be made." That city and this music mirror each other.

Buenos Aires resists the postcard format. No sombreros, no venerable ruins, no Club Meds. Packaged tourists bound for Latin exotica wouldn't risk dropping dead from picturesqueness there. They would be puzzled instead. For Buenos Aires rises unexpectedly at the southern end of the Americas with all the signs and symptoms of a metropolis. The sights are familiar: the busy and bustling downtown, the leisured suburbs, the rough edges, the subway crowds, the Lacoste shirts, the junkyards.

If it could have chosen its place on the map, Buenos Aires would have located itself conveniently in Europe rather than at this other end, between the vertiginous vastness of the pampas and the overlarge estuary of the taffy-colored Rio de la Plata. A sense of remoteness clings to the city. It is a port, open to all nostalgias. Not long ago, the portefios, the people of Buenos Aires, still secretly felt like vague distant cousins, seldom mentioned and never visited, who nurture in their estrangement unjustified doubts and a wounded pride. Far from Europe, far from the world perceived as real, they flirted with the idea of their own improbability.

As a popular joke goes, the portefios are Italians who speak Spanish, think they are British, and wish they were French. A quick glance at the names in the cast of Tango Argentino reveals the diversity of roots of the true portefios: some sound Spanish, others Italian, others Jewish or Polish or Lithuanian. Immigrants built Buenos Aires, and their children and grandchildren gave it its major emblem, the tango.

When we trace the tango to its elusive, muddy origins, another rich influence becomes obvious: that of blacks. It is thought that in the nineteenth century the word tango meant the social gathering places for ex-slaves. But time and history were to sweep away the black community. Blacks and mulattoes nourished the frontline troops of the independence wars and of the internal conflicts that ensued. In 1871 an epidemic of yellow fever further decimated them. The handful of survivors blended into the ceaseless stream of immigrants.

Basic steps of the tango, such as the corte and the quebrada, sprang from the carnaval street parades of the blacks. The hoodlums of the city, the compadritos, were a mocking but admiring audience for these quaint celebrations, and they adapted some of the figures—with a twist: unlike that of the blacks, theirs was a dance in which a couple held one another. Called the milonga, it was the prototype from which the tango evolved. A few decades later black pianists improvised, in shabby courtyards and dubious saloons, the perky music that accompanied tango steps.

The tango in the making belonged to a turbid, pernicious milieu at the edges of society. By 1880, Buenos Aires was a thriving port, the window on the world for a country of giant ranches and the last stop for hundreds of thousands of European expatriates. By 1895, foreigners made up 53 percent of the city's population. It was also full of ex-soldiers, for Argentina had entered an era of peace and stability and the disbanded armies rushed into the capital.

Buenos Aires was sharply divided into irreconcilable halves: the opulent fief of the elites—a studied emulation of Belle Epoque splendor—and then the outskirts, die orillas, where the lower classes and the newcomers dwelled. Over the geography of squalor the underworld spread its net. Prostitution reached significant proportions. International traffickers in white slaves took possession of the depths of the city. A police report of the time, known as the Red Book, enumerates in a sad, stark litany the provenance of the women: there were "Polish, Australians, French, Germans, Belgians, Turkish, Egyptians, Swedish, Persians, Circassians, English, Russians..." They had been lured to Argentina with promises of prospective husbands. They ended up in brothels. The tango was in the beginning restricted to the brothel. Only the hoodlums would take it into the open: agile male couples dancing on street corners were a regular feature of the slums.

One is tempted here to conjure up Pabst-like visions. Ideally, the tale should be told through the halting, tinny images of a silent movie. Theatricality pervades the brothel. It is a confined space where the same elementary passions are enacted again and again. As a self-contained universe, it establishes, logically, a code—a jargon, rules for dress, a hierarchy—that completes and secures its autonomy.

Among the characters on this infamous stage the pimp is the most conspicuous. The first tango lyrics glamorize him and chronicle his life from rise to fall. Just as some male birds flaunt their plumage, the pimp showed off in garish attire. His virility didn't prevent him from making up his face, Sarah Bemhardt-style, with white powder and kohl. As for his girls, they used to carry knives in their garter belts, and they would often fight each other for the exclusive attachment to a hustler.

Such is the first couple of the tango. In its primitive form, the dance symbolized their relationship—quite graphically so. And it was thus that the dance was transmitted to the patrons of the brothel, the working-class hoodlums who idolized the pimps. Later, men from the upper class penetrated this marginal institution and practiced the tango as a thrilling low habit, a trophy to bring back from their nights of debauchery. But the tango remained for a long time forbidden music, a damned dance. Eventually, it would jump out of the underworld into respectability—but not without first being stripped of its wicked characteristics when the official city gradually dissolved its depraved tumor, those outskirts that lodged, among other iniquities, 30,000 prostitutes and two opium dens run by Chinamen.

A large part of Tango Argentino is devoted to the colorful years of foundation, but Segovia and Orezzoli avoid the many obvious anecdotes. They proceed with strictness, never overelaborate, just let the tango be and the images flow: two thugs entwine and dance el apache argentino, men and women unite in the humble joy of some of those milongas of the struggling days, then Elba Ber6n sings, or rather bursts into, "El Choclo," a signature tango, frisky and blazing. The passage from shame to luxury, from the slums to the cabaret, is told in Tango Argentino through the history of Milonguita—another classic: a neighborhood ingenue, pretty but poor, of course, Milonguita is lured by the glitter of the posh nightlife and ends up a B-girl.

The tango became a tuxedoed bravo, began to drink champagne, sniff cocaine, and babble in French.

The furor over tango in Paris was the vogue that topped all vogues.

On its way up the tango itself had to overcome its past in order to be accepted. It lost some of its bellicosity, became a tuxedoed bravo, started to drink champagne, sniff cocaine, and babble a few words of French. As a dance, it toned down its overtly sexual mimicry. As music, it became more abstract, acquired a wider scope, and was capable of reflecting on all situations of life. By the 1920s the tango had already evolved into a highly refined musical form.

In the meantime, it had been to Paris— and driven the Parisians frantic. The selfappointed Argentinean aristocracy had little passion for passions. The implacable emotion of tango had left them unruffled. They would throw in the towel, with typical provincial snobbery, and embrace the tango only when the tango had received Paris's seal of approval.

The furor over tango in Paris was the vogue that topped all vogues. Sem, the brilliant caricaturist and social observer, wrote on the subject for L'Illustration in 1912: "This neurosis has made a terrible progress.... It has spread all over Paris, has invaded the salons, the theaters, the bars, the cabarets de nuit, the big hotels, the guinguettes. There are tango tea parties, tango exhibitions, tango lectures. Half of Paris rubs against the other half. The whole city jerks: it's got the tango under the skin."

A freak was bom: le tango—with the stress put on the last syllable. When after the horrors and miseries of war the Roaring Twenties erupted, with its strings of pearls and its strings of parties, le tango was alive and kicking. Kicking in a bizarre way—for this was a tango-for-expoit, played by orchestras in gaucho disguise and danced in an extravagant manner by gigolos and femmes du mo tide, a tango cosmeticized to the point of forgery. Fatally, it reached the Hollywood wonderland, where it became "curiouser and curiouser" in the flitter-flutter variations of Rudolph Valentino.

By then, the burgeoning middle class of Buenos Aires, now a prosperous town, had adopted the tango as a social and aesthetic experience. The tango entered its classical age. During the twenties Julio De Caro and Osvaldo Fresedo, each a musician, conductor, and composer, established its archetypal form. In cabarets, music halls, and caf6s an increasingly sophisticated audience admired the richness of the harmonies, the sumptuousness of the new sound, its elegance, the virtuosity of its interpreters. The orchestra triumphed. Fewer people danced the tango, but more and more listened to it, almost religiously. The lyrics increased in importance, and the radio brought an abundance of new voices. The public identified immediately with the Rositas, Azucenas, and Mercedeses singing over the airwaves, taking tango to its highest peak of popularity.

But Argentina is a macho country, and the dreams of the public crystallized on a man: the singer Carlos Gardel, whose rags-to-riches climb to the top seemed to have all the sweetness of revenge. He was a hoodlum and a bastard, bom to be a loser, but he magically flew to the rarefied heights of society. He was both the kid from the slum and the darling of the beau monde. Curiously, this supposedly quintessential porteno spent most of his working life abroad. One of his biggest hits was "Blondes of New York." The Lights of Buenos Aires, one of his many hit movies, was shot in Joinville, not far from his Parisian apartment. The fervor of Gardel's Argentinean fans cooled considerably over the years, but when he was killed in a plane crash in Colombia in 1935 his death plunged the whole country into a stupor of grief. Buenos Aires gave him a delirious funeral, and he was instantly frozen into pop immortality.

In 1930 a military coup had put an end to Argentina's liberal experience. The bleakness and desperation of the years that followed, years of poverty and unemployment coupled with repression and fraud, are the subjects of the tangos of Enrique Disclpolo, a popular poet of the period. In Tango Argentino, Carlos Gardel is evoked through "Mi Noche Triste" and "Cuesta Abajo" ("My Night of Sadness" and "Downhill"), while two of Disc6polo's classics—"A Desperate Song" and "Without Words"—are sung by Marfa Grana, today's rising tango star.

During the thirties, the Infamous Decade, the tango almost disappeared as a vital popular form but was preserved as an object of cultural importance. Its history was traced in theatrical shows, and in 1936 the first history of the tango was published. The talkies found the tango an ideal subject, and Argentinean tango singers were the brightest stars of Latin cinema.

In the forties new orchestras began to emphasize the rhythmic element in tango, and it was adopted as a social dance. Ballrooms proliferated. The key figure of this period was Anfbal Troilo, heir to the great masters of the twenties and a consummate bandoneon player. He held undisputed reign over the whole tango scene until his death in 1975. As a composer he created masterpieces to the words of the poets Homero Manzi and C&tulo Castillo, and his orchestra nurtured some of the most outstanding tango singers. Two of these appear in Tango Argentino: Elba Ber6n—who revives "Desencuentro," one of the songs specially composed for her by Troilo and Castillo—and Roberto Goyeneche, the veteran star who provides a dramatic crescendo to the show's grand finale.

Anfbal Troilo maintained the tradition and the purest qualities of tango intact, becoming a living legend even after rock 'n' roll had burst upon Argentina in the fifties and the tango itself had gone into a permanent partial eclipse. Today, purists treat it as a cult and wouldn't be caught dead in the caf6 concerts where tango is offered to tourists—even though these shows are usually first-rate. On a popular level, the tradition is kept alive on a few star-studded prime-time TV shows.

Now, at the very end of this story, comes Tango Argentino, a dream made of tangos and nothing but tangos. It comes to us bare of all embellishments, coated only with a shimmering elegance.

The tango is a tease—but a well-mannered tease. It is wicked, its insolence conceals an innate finesse. The tango is somber too. The Argentinean novelist Ernesto Sdbato speaks of "the gloomy ec/ stasy of bandoneon." The tango is grave, dense, whimsical. It says "no more tears" and then it weeps; the next minute it is smiling. Tango lyrics need no translation. Their emotional impact is such that when Jovita Luna, a female matador with a nocturnal, throaty voice, sings the "Ballad for My Death" audiences from Paris to New York know some central mystery is being approached.

And then there is the dance. When the couples in Tango Argentino (Juan Carlos Copes and Marfa Nieves, N61ida and Nelson, the Dinzels, Carlos and Marfa Rivarola, Gloria and Eduardo, Mayoral and Elsa Marfa, and the soloist, Naanim Timoyko) take possession of the stage we realize that we are sharing a precious secret. Their dancing is more than impeccable technique, acrobatic feats, the ebb and flow of sensuousness, more than an enthralling ballroom routine. One senses that they are accomplishing an act of faith. A man and a woman, each wrapped in their own reverie, both trapped in the same fated embrace, unravel—or attempt to unravel—with their bodies the figures of a ritual. One thinks of Jean Cocteau's advice to all artists: "Consider the metaphysical as a prolongation of the physical."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now