Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSon of Brideshead

AUBERON WAUGH writes about his upstairs-downstairs life in various English country houses. And MARC caricatures some notable owners of stately homes

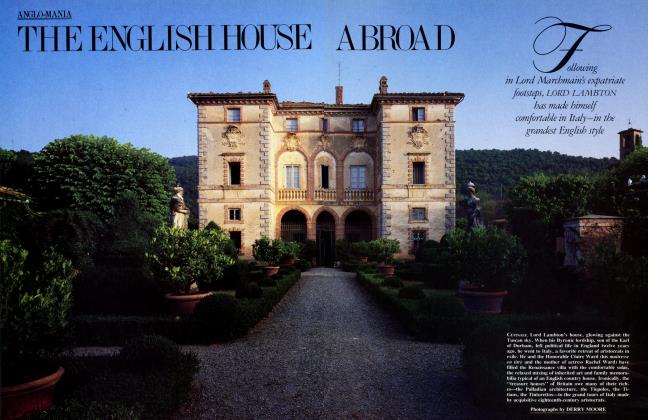

ANGLO-MANIA

he historian A. L. Rowse, who is now eighty-one years old and lives rmuch of the year alone in his surprisingly grand Georgian manor house on the Cornish coast near St. Austell, has decided that in the entire history of civilization the pleasantest form of human existence devised was that of the large English country house in its heyday. Even so, I could not help thinking when I visited him there a few years ago that it is a curious place for an elderly bachelor to live, especially one of no great wealth. The English country house, described in the National Gallery's catalogue of the upcoming exhibition as a "vessel of civilization,'' offers few joys to a solitary and aged inhabitant.

It occurred to me that Dr. Rowse was born a month after my own father, Evelyn Waugh, who made a sort of cult of the grand country house in Brideshead Revisited. Rowse, as he never tires of pointing out, was bom into the Cornish working class. Waugh's father was a London publisher. Both men saw it as a normal and natural aspiration in life to acquire a large country house to live in. That was the only life worth living. There was no other good reason for working hard being successful, acclaimed, famous.

Evelyn Waugh's first country house —Piers Court, in Gloucestershire— was an enchantingly pretty gentleman's residence in the classical taste, with all the attributes of a very grand stately home except size. It also possessed only forty acres of land by way of ancestral estate. He filled the house with his collection of Victorian paintings, with a butler, a housekeeper, a cook, a nanny, a nurserymaid, and another maid. He hired two men to look after the garden and small farm, and most of the village to come up and clean on a daily basis. Then he sat down and had himself photographed with all his household dependents around him. Perhaps it was his proudest moment. Thereafter the twentieth century began to exact its toll. With six children, he found the house, which had only nine bedrooms, oppressively small, the servants too expensive. It was a chastened author who moved to a much larger house in Somerset in 1956. An Italian cowman doubled as butler, but he never got himself into the butler's outfit of black morning coat and striped trousers. Instead, he waited at table in a sweater and jeans. His wife, the cook, was the only other live-in servant. She was given to various neurotic fantasies. Before long they left, and my father's last years were spent alone with his wife in the huge house, with no interest in rural pursuits, no great inclination to surround himself with roistering friends. By then the English country house, vessel of civilization or not, had become a place of retreat from the horrors of modem society rather than somewhere to celebrate its finest fruits. My father died in 1966. Since then, living in the house which he left, my wife and I have watched the pattern of country-house existence change from the pale shadow of its glorious heyday into a new form of sanity and enjoyment.

The English country house took a tremendous bashing in the Second World War. Many of the greater stately homes, like Brideshead Castle, were requisitioned by the military. Others became hospitals or were converted to some more sinister purpose, like Blenheim Palace, which became a center for military intelligence. My own family home at the time, Piers Court, became a convent boarding school, and I was sent to spend the war at the much larger house of my mother's family: Pixton Park, Dulverton, Somerset, standing in four thousand acres of magnificent Exmoor countryside with trout and salmon fishing and wild red deer wandering over the park for anyone who felt the urge to take a potshot at them. Unfortunately, Pixton had also been requisitioned. About forty evacuee children from the East End slums of London were sent there for the duration of the war. They lived on the top floor of the huge house with their keepers, while the family and its guests lived on the second and ground floors. The house was built around a large interior well which rose from the hall to a skylight in the roof. It was not long before the evacuee children discovered that by sticking their heads through the wooden balustrades around this well on the top floor they could spit on anyone walking across the hall two stories down. They seldom scored a direct hit, but anybody who walked across the hall did so to the accompaniment of little splashing noises all around. This was my first experience of the class conflict in Britain that was to occupy so much of the country's time after the war, and still occupies it now.

These large country houses, although monuments to the British class system—and, even more, to the cruel and unnatural system of primogeniture, by which the oldest son in a family inherits all the loot—were not, in fact, ever designed as fortresses or beleaguered outposts in a class war. Pixton, in wartime, may have been in the vanguard of social change, but after the war it returned to its original role as an oasis of social tranquillity. Until dramatically increasing wage levels and the imposition of a punitive level of income tax on the very rich led to the disappearance of servants, these large country houses, with their carefully graded hierarchical structures and impressive varieties of people all living under the same roof, were models of social coherence. They were more like cooperative community workshops than anything else: one large house would have its own bakery, laundry, flour mill, brewery, even its own blacksmith. It also furnished sustenance for innumerable gardeners, woodmen, gamekeepers, estate carpenters, and laborers in outlying cottages and farms. No doubt the purpose of these community workshops was to provide for the comfort of the squire or nobleman and his family, but all the other people in the business did very well for themselves, too.

And the country houses were also centers of endless hospitality. Pixton had practically no servants at all during the war—one woman upstairs to make the beds, one to tidy the ground floor, lay the table, wash up, and look after the fires, and a cook. All were elf derly and at least two were deaf. But the house saw a stream of visitors. One was Hilaire Belloc, the poet and writer, who became a family friend after being employed as my (maternal) grandfather's tutor. On one occasion, my father found him in the drawing room in a great rage, pulling on a long bellpull that had not been connected to any bell for at least twenty years. "Zee footmen, zay sit in zee pantry and zay say: 'It is a poet who has rung. We shall not go.' "

Evelyn Wiugh saw it as a normal and natural aspiration in life to acquire a large country house to live in. There was no other good reason for working hard, being successful, acclaimed, famous.

On another occasion Mr. Belloc found me, a scruffy four-yearold, in the library and decided I must be one of the evacuee children who had escaped from the top floor. He ejected me with a well-aimed kick. But I got my revenge on the evacuees before they left. After they had been there for about six months, the house was invaded by a swarm of rats. Whether the evacuees brought these rats with them from London, 150 miles to the east, or whether the rats had been attracted by their presence was never established. But the local ratcatcher was called in, with his bag full of poison and his long spoon. I watched, fascinated, as he laid down the poison, and then went and told my grandmother, quite untruthfully, that I had seen the evacuees eating it. At a hastily organized identity parade, I picked out about fifteen of them—some at random, others who had already established themselves as my particular enemies. They were all taken away to be stomach-pumped.

In the twilight years of the country house there was a complete reversal of the decorum and concordia ordinum that had existed in the servants' halls of England's great houses before the deluge. Host and hostess alike became worried if a man sat too long over his port after dinner. The servants had to be considered, poor things. Previously, in the heyday of the country house, servants rose at five o'clock in the morning to clear the debris (including chamber pots left full in the dining room), arrange the rooms, and lay the fires. In this twilight period, servants stayed up until ten at night only as a great personal favor. There was no question of their turning up for work before 8:30 or 9 in the morning. So everybody had to be put out of the dining room by 9:30 at night.

Today, under the new order, weekend guests can remain carousing until any hour. The host merely shuts off the room concerned, with all its dirty plates, full ashtrays, and broken glasses, until the daily cleaners arrive on Monday morning. He and his guests move into another room for Saturday and another for Sunday. It may not be very hygienic, but it works.

A few of the treasure houses—Chatsworth is the most obvious example—are still kept going on an incredibly grand scale, although the real comfort nowadays is chiefly to be found , in smaller stately homes, like Basildon Park, near Pangbourne, in Berkshire—the home of Lord Iliffe, a provincial press baron. In such places guests generally arrive after 6 but before 7:30. They have their suitcases carried upstairs and unpacked, their evening clothes laid out on their beds, and their baths run for them. They are given cocktails in the drawing room until about 7:30, when they go up and change for dinner.

On descending, in the best-conducted houses, they will be offered only sherry before dinner, but it is worth remarking that the English upper classes start drinking at six o'clock in the evening and do not stop until they go to bed after midnight. Women were expected to drink less at one time, but this has largely gone by the board. By normal medical standards, a significant proportion of the professional and upper middle classes of Britain are certifiable alcoholics, but the strict conventions of timing and personal behavior always prevented it from showing. Today, when the hostess is as often as not responsible for cooking, dinner may not appear until nine or even ten o'clock, and nobody changes, it shows rather more.

With dinner (in comparatively humble homes, until five or ten years ago, a large house party would always have been waited on at table) one drank and still drinks two or even three wines, followed by port, brandy, and liqueurs. Whiskey and soda appear at about ten o'clock in the evening and continue indefinitely. The convention that ladies wi withdraw to have their coffee separately, relieve themselves, and chatter about feminine subjects was somewhat undermined, as I have said, by the servant problem during the long twilight of the country house. It was further undermined, during the sixties, by the women's movement, which tended to ridicule men's preference for their own company. After half or three-quarters of an hour, the men would rejoin the ladies, redfaced and puffing, to be accused of having told each other dirty jokes all the time they were absent. In fact, nowadays they are as likely as not to have been talking about business— bankers, in particular, feel they have some divine dispensation to bore everyone else with their concerns; politicians and political journalists are as bad. But with the growth of a robust and articulate misogyny in response to the women's movement, the port habit seems to be coming back. At any rate, I have invested in vintage-port futures, to the extent of heavy purchases of 1970 Taylors, 1977 Fonsecas, and 1983 Cockbums, which will not be ready to drink for five, twelve, and fifteen years, respectively.

Once the house party has reassembled in one or at most two rooms, some go to make up a bridge four; others may play backgammon, billiards, snooker, table tennis, or sit around talking. Determined hostesses may organize charades or other party games involving pieces of paper, but these are rather going out of fashion. When the older generation retired to bed, the young people used to get up to all sorts of pranks—at a house party in the North of England, it was thought amusing to take a pony into one of the guests' bedrooms and leave it there. When my wife, as a young thing, was staying with Lord Bute at Dumfries House, it was decided that one of the guests had an objectionable hat. It was shaved, set alight, and carried on a stick through all the Adam saloons and galleries to the accompaniment of ribald songs. Today, one notices, young people seem more interested in sex and soulful conversation.

But the older traditions survive. After a dinner in the West Country recently, the host decided it might be amusing to hold a chicken shoot by moonlight. Chickens were tossed from a bam, squawking, while guests blazed away. When the late Sir Richard Sykes was staying at Wentworth Woodhouse with the Fitzwilliams, other guests shortsheeted his bed. In fury, he threw all his bedroom furniture out of the window and stormed out of the house.

Sir Richard, who owned Sledmere, in Yorkshire, was a man of notoriously evil temper. The above story gives some idea of the dangers faced through the years by these treasures of Britain in their vessels of civilization. A guest who was staying at Sledmere in Sir Richard's day sat on one of ten Chinese Chippendale chairs in the music room and broke it. He was so terrified of Sir Richard that he smashed it into little pieces and put it on the fire. Now there are nine. One of them is to be seen at the National Gallery show, along with Romney's portrait of an earlier Sir Christopher and Lady Sykes.

Breakfast has gone very much downhill since the heyday of the country house. Even now, in the grandest houses, married women have breakfast taken to them in their bedrooms, while their menfolk and younger, unmarried women go downstairs to face a huge array of dishes in the minor dining room. But in less formal modem surroundings, breakfast is a meal that starts at 9 and goes on until about 12:30, with guests wandering around sometimes dressed, sometimes in dressing gowns, burning toast and dropping eggs on the floor.

If it is a shooting or hunting party, guests then go about their various occupations. Unmarried females, desperate for husbands, sometimes accompany the guns. Lunch is usually taken in some remote lodge or hut on the estate. Other guests amuse themselves at croquet, tennis, swimming, or just wandering around. In the course of a famous house party at Glamis Castle, Angus— the home of the Queen Mother's family—the guests decided to investigate rumors that the castle contained a monster, said to be a hideously misshapen heir to the earldom of Strathmore, while their host and hostess were away. They hung blankets and sheets out of every window. Sure enough, there were three windows unaccounted for. It is said that every Lord Strathmore, on inheriting the title, is let in on the secret, after which he never smiles again. But the only time I saw the present Lord Strathmore he was laughing like a hyena.

Perhaps the greatest misunderstanding about the huge palaces that adorn the English countryside and survive, for the most part, as museums is to suppose that they were often the centers of a glittering world. In each generation maybe five or six of the great houses were inhabited by people who could be described in those terms, and it is around those five or six noble families who held court in each generation that the myth of aristocratic England has grown. The rest of the houses have always been inhabited by people of limited intelligence or interest in the outside world. Their lives revolved around agriculture, hunting, sometimes horse racing, and shooting. Apart from shooting parties, house parties for race meetings, and the very occasional ball, they would invite few people to their houses except poor relations, who came to stay, and neighbors, who came to lunch or dinner. Guests who came to stay would be likely to remain a week or a fortnight—the weekend is a comparatively recent invention, geared to a world where most people work in London during the week. Four huge meals a day were the main events, but it was only after dinner that the house party would really come together for charades or amateur theatricals, or even (if there were young people among the party) such childish games as hide-and-seek and murder in the dark—the opportunity for some harmless and tentative first sexual advances among the young, but seldom leading to much action.

Of all the vulgar misapprehensions about life in the great English country houses, the idea that is most pathetically far from the truth paints it as one great sexual orgy, with regular wife-swapping trips down long corridors in the small hours. No doubt a few louche, plutocratic Edwardian house parties degenerated in that way. No doubt a number of "Society" divorces started with a little flirtation over the bridge table, a stolen walk in the shrubbery. But in the vast majority of houses decorum was observed, and it would be thought immensely bad manners to conduct an affair in the house of a friend. Nowadays, of course, illicit couples regularly descend from London for the weekend and expect to be put in the same bedroom, returning to their husbands and wives on Sunday evening. But that is a development of the last fifteen years.

Our day started with breakfast in our nursery at 8 a.m. At 9 o'clock to the sound of a gong we descended to the Hall where we greeted the elder generations with awe and respect, not to say fear. Meanwhile the footman brought in a long bench which he placed in front of the billiard table and chairs at both ends for the upper servants. Then entered a very tall white-capped Mrs Atkinson, the housekeeper, followed by the ladies maids and a diminishing line of white capped maids, then the usher, the footmen and finally Mr Jack the Butler.

This account, written by my wife's greataunt Margaret Sophia, describes childhood visits—in the 1880s—to stay with her grandfather Sir Henry Dashwood, at Kirtlington Park, Oxford. Entertainment for the children at Kirtlington consisted of walking round the park and gardens, f visiting the laundry, with the "wonderful smell of ironing hot linen"; the cobbler's shop; the beehives; the gamekeeper's cottage, full of stuffed animals, including a chicken with four legs; the dairy; the flour mill; the bakery; the stable block; and the Park farm, "where we would gaze in awe and wonder at the bulls." (I fear that this study of the bulls may have been the only intimation of sex available in that melancholy house.)

One should always remember, in admiring great pleasure palaces such as Kirtlington Park and calling them polite names like "vessels of civilization," that they were sustained by appalling injustice. Daughters and younger sons of the nobility often spent their lives in penury, relieved only by an annual visit or two to the Great House, while their older brothers spent the whole year surrounded by treasures of art. One should also bear in mind that these elder brothers were often extremely stupid and primitive people who appreciated their dud ancestral portraits more than their masterpieces of the Italian seicento, and probably preferred their stags' heads to both.

No words can exaggerate the stupidity or boorishness of the late Duke of Marlborough, called Bert, who spent most of his time in the splendors of Blenheim Palace in front of a television set, insulting anyone who came close. The present Duke of Bedford's father, Hastings, was a lonely and embittered Fascist who shocked the House of Lords by making an impassioned speech to their lordships in defense of Hitler in the middle of the war. His father, Herbrand, was a mad recluse who lived alone in the splendors of Woburn Abbey on a diet of spring onions. The long gallery at Longleat, in Wiltshire, full of priceless paintings and statuary, was used as a bicycle track by the young children of Lord Bath. Even the present Duke of Devonshire, by no means a philistine, surprised the art world when he was asked to lend a seventeenthcentury painting to an exhibition at Burlington House. He revealed that it had been sawed in half to make a service hatch in the dining room at Chatsworth.

The vast majority of the English aristocracy throughout its history, or at any rate since the seventeenth century, has been interested in nothing but horses. A typical case was the late Duke of Beaufort—a man universally loved for his benignity—who, despite living in the unrivaled glory of Badminton House, Gloucestershire, reckoned that any time not spent hunting was time wasted. When he died, last year, a group of antihunt terrorists tried to dig up his grave. It was a signal example of the way the class war in Britain (itself, as I maintain, a product of the unnatural system of primogeniture) has spread to the English country house. Our spiteful inheritance taxes mean that those with even a modest property must be prepared to see 60 percent of its value confiscated on death. Mrs. Thatcher's second Conservative government has done nothing to relieve the intolerable burden of this tax—in fact, if anything, she has made it more difficult to avoid. One suspects that large sections of the British Conservative Party suffer from what might be called the younger sons' complex. With the preposterous values placed on works of art nowadays— largely as a result of Paul Getty and American foundations—it will not be long before few, if any, of the contents of Britain's treasure houses remain in private ownership, and few enough will remain in Britain, although a socialist government will probably prohibit their export without compensation to the owners. Every generation produces at least ten noblemen who are mined by these capital taxes and have to sell up, as well as a few—like Lord Warwick's heir, who decided to dispose of Warwick Castle with all its contents in order to live a life of luxury abroad—who opt out. My own view, which is hard to justify scientifically, is that at this late stage of the game every work of art which moves from private ownership into the public sector—whether becoming the property of a state gallery or of some great American foundation—represents a net loss to the sum of human happiness.

(Continued on page 121)

(Continued from page 71)

Conrad Russell, the friend of Lady Diana Cooper, who was a cousin of the Duke of Bedford, wrote to Lady Diana after the death of one of his ducal cousins: "Woburn makes anyone believe in the curse on Church property. There's been no happy normal life there since Great-Uncle Bedford died in 1861. Since then we've had old William, Uncle Bedford, Tavistock, Herbrand and Hastings. It makes six in succession all unhappy, tragic figures. If I had Woburn I'd make it a showplace with restaurants, swimming pools, dance-halls, car parks, guides for four summer months and let the public have a good time..."

Under the influence of people like Conrad Russell, the younger son of a younger son, this is exactly what has happened, of course. Wobum is now something between a museum and a funfair. Clandon, where my wife spent her childhood as the only daughter of the last Earl of Onslow to live there, now belongs to the National Trust. Go and stay with the bouncy young Duke of Roxburghe and his attractive wife at Floors Castle and you will find notices up all over the place pointing to tourbus parking lots and public conveniences. Longleat is now situated in the middle of a wild-game park; the small apartment kept private for Lord Bath's heir, the eccentric Viscount Weymouth, is decorated with his own mildly pornographic pictures, which he seems to prefer to the treasures of seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century art available to the public.

A part from these palaces and treasure houses, the English-country-house tradition survives, chiefly in the larger manor houses and minor magnates' seats, where life, mysteriously enough, manages to continue despite the disappearance of those ten indoor, ten outdoor servants once considered essential—and despite the vindictive and confiscatory tax system that the whole apparatus inspired. The penalties of living out this fantasy are severe enough. In my own modest, twenty-five-room home, the cost of heating became so astronomical five years ago that we now shiver throughout the winter, as earlier inhabitants did throughout the centuries, with two or three rooms heated by open fires and icy stretches in between. The burden of maintenance, where a slipped tile in the roof or a burst water main can cost tens of thousands of pounds without any warning, means that any pretense of continuity or permanence is a sham. Pictures disappear from the walls from time to time—or pieces of furniture from the bedrooms—and reappear at Christie's or Sotheby's as the only possible means of keeping the show on the road.

But in spring, summer, and early autumn, it all seems worthwhile. The pleasures of the English country house, as they survive, are not so different from what is available at some American country clubs: hunting, tennis, croquet, fishing, bridge, backgammon, billiards, table tennis, walking, bicycling. The big difference between English-country-house life and the American country clubs is that in the former everything is free (at least for the guests), everybody knows each other, and everybody is gathered together to celebrate a certain idea of what life should be about. It is a life dedicated to decorous pleasures, to good manners, and to the joys of civilized conversation.

In the last ten years, almost unremarked in the public consciousness, there has been an extraordinary diaspora of the educated English. Read any oldboys' list from the top twenty schools in England and you will find that about two out of every three people on the list are currently living abroad. In the United States or Canada in many cases, but chiefly in the Middle East: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the Persian Gulf. These are the regions where nobody in his senses really wants to live, but where there is quick money to be made. Talk to any of these exiles on the dry, inhospitable shore of Islam and you will find that they all sustain themselves more than anything else by reading the pages of three or four English magazines that carry advertisements of large country houses for sale: Tatler, Country Life, The Field, possibly Vogue or Harpers & Queen. They all dream of green lawns smelling of mowed grass, where the birds sing and the scent of roses drifts through their bedroom windows in the morning. They all still think of a world where those less fortunate than themselves are friendly and respectful, where newly laundered linen sheets appear as by magic on their beds every morning. It is the one vision that England has given to the world, and the vision to which much of England still clings.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now