Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDESPERATELY SEEKING SUSAN

Journalist Susan Crosland left Baltimore to take British politics and society by storm. Now she sails home with her sexy novel to make waves in the U.S.

AUBERON WAUGH

Boohs

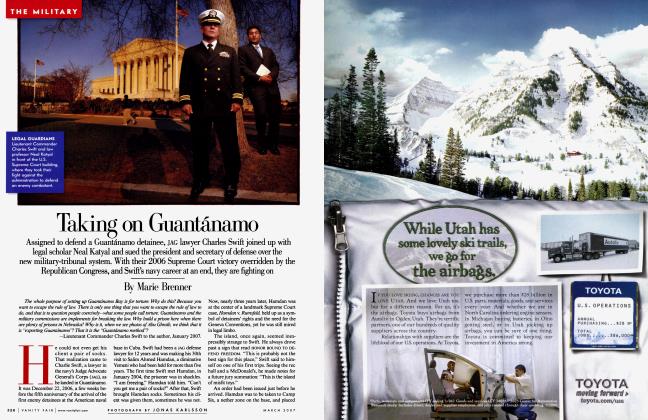

Who is Susan Crosland? America lost sight of her when she left her Maryland home as a very young woman to seek freedom, fame, and fortune in Britain. Never mind that she was a young woman with two infant daughters in tow, and an English husband she had found in Baltimore. She is a rare example of the buccaneer female returning from the New World to conquer the Old.

Other American women have broken through the rigid lines of London society, but they have nearly all been heiresses married into the aristocracy. Susan Crosland had no fortune: a pretty face, a pretty wit, and an engaging old-Baltimore manner carried her to the top of one of the meanest and most competitive professions in Britain. Journalism is also considered one of the least-loved callings, but her place in London society remained serene.

When she married her second husband, the brilliant young Labour politician Anthony Crosland, in 1964, he immediately soared off to become a Cabinet minister. At the time of his sudden death, in 1977, he was secretary of state for foreign affairs. Her long period of mourning produced the strange, haunting biography Tony Crosland (Cape, 1982), which can be found in nearly every intelligent, literate English household, but was never published in the United States.

America caught at least one glimpse of her in the course of her dizzy rise in London. In 1976, at the time of the U.S. bicentennial celebrations, the Queen of England visited the former colony on the royal yacht, Britannia. Apart from her husband, Prince Philip, various ladiesin-waiting and court officials, and one Foreign Office mandarin, the only guests on board were the foreign secretary, Anthony Crosland, and his embarrassingly attractive, much younger American wife, Susan.

Susan distinguished herself on this

visit at an official banquet given by the Queen for President Ford at the British Embassy in Washington. Sitting one down from the Queen, between Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, she found the heat oppressive, passed out, and broke her jaw. This was scarcely her proudest moment, but messages of condolence soon arrived from the U.S. president, vice president, and secretary of state, and the Queen and prime minister of England.

It was not a bad way to return to the little old country—a young woman who had left it virtually penniless to seek her fortune in England only a few years earlier, returning aboard the Queen of England's yacht to entertain the president of the United States at dinner.

America will get another chance to see her in May, when she arrives to promote her blockbuster erotic thriller, Dangerous Games. Five years ago, Crosland decided to try her hand at writing best-selling novels. The first, about a coltish American sculptress of twentythree, newly arrived in London in the middle of an affair with a Jewish American academic who seems dangerously to resemble Dr. Kissinger, was called Ruling Passions. The heroine, Daisy Brewster, marries an English politician who later becomes defense secretary in London just as her American lover becomes secretary of defense in Washington. . .

That book went straight onto the bestseller lists in Britain and did well in the United States. But it is the second novel, Dangerous Games, which is being geared up to hit the big time in America.

This time she spans the power structures on two continents. Her heroine is Georgie Chase, attractive, successful editor of a well-known New York newsmagazine at the dangerous age of thirtytwo, awkwardly married to a famous Washington political columnist and languidly considering an affair with Jock, a gorilla-like lobbyist and power broker who may be the most powerful man in Washington, and whose amoral assistant, Lisa, seduces Georgie's husband. Georgie's best friend is married to (dare we guess?) an English Cabinet minister, whose philandering habits get him into a serious mix-up with the I.R. A_In ad-

dition to some memorable sex scenes and a terrorist double murder, somebody (one of the more attractive characters, I thought) comes to an appalling, sticky end between two Doberman pinschers.

When Random House publishes Dangerous Games in May, a woman who is famous in Britain will be launched in the land of her birth and upbringing. American readers will want to know more about this countrywoman of theirs, whose story is no less bizarre than anything that has tripped off her pen since she became a novelist. Who on earth is she?

To be asked to compose a profile of Susan Crosland is rather like being asked to sing an operatic aria before Pavarotti, or dance a pas seul in front of Dame Margot Fonteyn and Nijinsky. Long before she became the thinking reader's Jackie Collins, Crosland more or less pioneered her own style of journalistic profile, which has since been imitated everywhere. It relied upon the distinguished, usually male subject's discovering a new joy in talking about himself to an attractive interviewer who was sympathetic and challenging simultaneously. She wrote these profiles mostly for The Sunday Times, and her subjects included Lord Hailsham when he was Britain's tetchy lord chancellor, King Juan Carlos of Spain, the King of Morocco, the Sultan of Brunei and his wives, and Prime Ministers Shimon Peres, Yitzhak Shamir, and Felipe Gonzalez. The pieces were later collected in two books, Behind the Image in 1974, and Looking Out, Looking In in 1987. An example from the first shows her ease and perspicacity with a man as prickly as Gore Vidal:

He remains utterly mystified as to why the Western world will try to combine lust and compassion. "The two are separate and most people know it. But they won't face up to it. Instead they put themselves through all this misery about 'love.' "...

Supposing, I said, you had some human beings who apart from romanticism might intellectually choose to combine body and soul in order to heighten a relationship. "Then they're putting all their eggs in one basket," he replies. He would never let himself in for the extreme pain that attends one partner in such an intertwined relationship.

Three years later, a widowed Susan would discover at first hand the pain that Vidal chose to avoid.

Her White House interview with Nancy Reagan in the second volume illustrates her eye for the telling detail:

She crosses her legs and folds her arms—not in the aggressive way, but instead tucking her hands under her upper arms, seeming almost to be protecting herself. In our hour-plus together, she unfolds her arms only to make a graceful gesture to illustrate a point. Then she wraps herself up again. It's her face that shows the most response. The enormous eyes are fixed on me throughout—except when she laughs or speaks of an acutely painful subject.... Then her face withdraws its expression. "The early childhood certainly left its mark," she says.

When I put the question to her about the rumored appearance of Henry Kissinger in her first novel, Crosland gives a soft laugh. "All that speculation about Henry K. being the original for Carl Myer in Ruling Passions was rather hard on Dr. Kissinger. Just because in real life he and Tony were their countries' foreign ministers at the same time, and Henry ate in our kitchen and so on, why should that lead readers to suppose the real-life situation was remotely like the

Long before she became the thinking reader's Jackie Collins, Crosland pioneered her own style of journalistic profile.

sexual triangle in my novel?" Methought the lady did protest too much. "Apart from anything else, in the novel the American Cabinet minister conducts his clandestine affair with Daisy in that high-security suite at Claridge's. So far as I can recall, I've never in my life visited a gentleman in his suite at Claridge's, though I once interviewed Porfirio Rubirosa in his suite at the Ritz and barely escaped 'with my clothes undisturbed'—as the police like to phrase these matters.

"I had to ask Ray Seitz to tell me in detail how on earth an American Cabinet minister in charge of the nation's defense—all those guys with their walkietalkies perpetually outside his door—is able to keep an affair private. Ray said the aide is the key."

Raymond Seitz's latest manifestation is as the American ambassador to Britain. "When I sent him the final draft to make sure I had got the security arrangements right, obviously I sent only the relevant pages. Ray complained bitterly at the bottom of one page, where I had no more security questions and broke off just where Daisy begins to remove her clothes." Susan begins to laugh again. " 'Holy cow! You cut me off just at the good part!' was scrawled in his red ink."

The Susan Crosland who can call up such high-level assistance when composing her torrid blockbusters is a blonde, feline, very attractive, very high-class single woman in her fifties. She lives in a large and beautiful London apartment in one of South Kensington's garden squares. She also has an old millhouse by a stream near Oxford, where she goes on weekends.

In her smart London apartment, she gives small but costly dinner parties of great elegance, waited on by a smiling Spanish maid. At them, one is likely to meet such normal people as Ray Seitz or Ewen Fergusson, the British ambassador in Paris; a serving Cabinet minister, perhaps, like Michael Heseltine, with his wife, Anne, or one who has just resigned in dramatic circumstances, like Nigel Lawson; Britain's most glamorous TV anchorwoman, Anna Ford, perhaps; a publisher or two, a shadow minister from the Labour opposition, even a journalist. What is memorable about these parties is that despite the grandeur of the guests they are always happy events, full of laughter and friendliness; the guests seem to be mysteriously united by their affection for the hostess who brought them together, with her soft Maryland voice, her southern hospitality, and her reckless sense of enjoyment.

Her apartment is also her office, where she writes, and she refuses to meet anyone for lunch. "I work in the day and play in the evening"—although even then she insists on waking up in the morning alone. At all other times, she lives by herself in that large and beautiful apartment, without even a cat to disturb her solitude. Mrs. Crosland is alone. And she loves it.

Just as she struck out as a young woman to make her way in England, her two daughters have chosen to move on—one slender, dark beauty to Los Angeles, the other slender, dark beauty to Greece—and, while remaining on the warmest sisterly terms with them both, Susan is free.

"It is a terrific sense of freedom when your daughters have flown the nest. 1 love my freedom. I love the irresponsibility," she says. At the time of writing her most serious work to date, the moving biography of her husband, written while she was still in mourning for him, she announced that she was "monoerotic"—incapable of being sexually attracted to two people at the same time. Now she is not so sure. She is very happy to keep her friends in separate compartments, allowing them to call on her, but she is equally determined to live for the present, to make no commitment to anyone.

Somewhere in her fifties, she reached the position most fervently desired by a large part of modern womanhood. She can do what she likes. Her erotic thrillers are a success. She has the respect and admiration of her friends, and anyone who inquires into the private compartments of her life is likely to get short shrift: "What's it got to do with you?" (always said in that soft, musical voice). What remains to be said is that her route to this happy state has been a somewhat circuitous one.

It was in the mid-fifties that a clever young English politician named Anthony Crosland published a book called The Future of Socialism. The book caused something of a sensation because, although it was written by one of the leading socialist thinkers of the day, a bulwark of the English Labour Party, it seemed to say—thirty-five years before Boris Yeltsin reached the same conclusion—that socialism, although undoubtedly a very beautiful idea, did not actually work. It had no future, at any rate in the sense that Marx, Engels, and Lenin defined it. Crosland retained some romantic notions about liberty and equality, believing that increased prosperity would somehow be able to finance them both in a Keynesian mixed economy, but he accepted that the old Marxian idea of class struggle leading to the dictatorship of the proletariat had been discredited. The effect was instantaneous. Nobody paused to consider that liberty and equality might be uneasy bedfellows, not to say mutually exclusive. Where previously it had been considered rather smart to be left-wing, it suddenly became rather smarter to be slightly less left-wing. Crosland was the hero of the hour.

Just then, Susan Catling set foot in England for the first time. Born Susan Watson, daughter of a distinguished, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and holder of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Susan had divided her childhood between Maryland, home of her maternal family, called Owens, since the seventeenth century, and the Vermont shore of Lake Champlain, where the Watsons had settled. The Owenses were tobacco growers who went to Baltimore after the Civil War. One of them became editor of the Baltimore Sun. Mark Watson, Susan's father, also became an editor of The Sun, although he was chiefly famous as the most read and most highly respected defense correspondent in America.

Nothing could have been more natural than that on graduating from Vassar at the age of twenty the popular "Sunie" Watson should marry a tall, handsome, sardonic Englishman on the staff of the Baltimore Sun, Patrick Skene Catling, soon to be posted on a temporary assignment to the London bureau, with the new joys of an expense account.

"All that speculation about Henry K. being the original for Carl Myer in Ruling Passions was rather hard on Dr. Kissinger"

Sunie, now Susan Catling, accompanied him, with their two baby daughters. The marriage was in a somewhat rocky state. Now, with a nanny to look after her daughters, Susan had the first taste of a freedom she had never known. When the Suez fiasco erupted, Patrick was sent to cover it for the Baltimore Sun, on the time-honored American principle that Britain and Egypt, being both abroad, must be pretty well next door to each other. While her husband was away, Susan went to a small cocktail party in South Kensington, where for the first time she met Anthony Crosland.

One afternoon, near the end of the Catlings' stay in London, as Susan records in her biography, Tony Crosland said to her, "I'm putting my promiscuity aside until you leave England."

"Why?" she replied. "You've taken trouble enough to make me understand that it doesn't diminish what we have."

"Which it doesn't," said Crosland. "But I want to make the most of this."

The year after this endearingly brusque English courtship, the Catlings were back in London, but under different circumstances. Patrick had left The Sun and gone to work for Punch. Money was short. Susan presented herself to the editor of the Sunday Express, apologizing for having no evidence that she had been a practicing journalist in America. "I left my cuttings in Baltimore." Whether he believed this blatant lie or not, she got her first job as a journalist, and within months her profiles had begun to make her name nationally. "The real miracle," she says, "was discovering that my earnings made it possible— just—to support my two children on my own." She separated formally from Patrick—which may confirm male fears that if a wife goes out to work she can manage quite well without a husband.

Her marriage to Crosland was an extraordinarily happy one—very rare in the upper rungs of British politics. "It is odd to find yourself suddenly at the center of power," she says now. "Most wives have a long time to wait for this and think about it. With me it happened only months after I married Tony, when, at the beginning of 1965, he became secretary of state for education. And except for 1970-74, Labour was in power throughout the thirteen years of our marriage. So when people asked what it's like to be a Cabinet minister's wife, they might as well have asked what it was like to be Tony's wife. Boring it was not."

As head of education, Tony Crosland could put into practice his belief in greater equality. "Obviously," Susan says, "nature will ensure that an elite keeps rising in a democracy, but the state should do its utmost to make it possible for those without money or position or a literate family background to have equal access to the opportunity that a decent education bestows. That's why Tony introduced comprehensive schools in Britain. In things like socialized medicine, Britain is ahead of America. But Americans have always led the way on state education. My American friends could hardly believe it when they discovered that British comprehensive schools are no more and no less than the public-school system that Americans have taken as their right as long as anybody can remember. Yet in 1992, if you please, some Tories are still trying to reverse the comprehensive system.

"Thirteen years of Tory government, eleven of them under Thatcher, have had this curious sponging effect on the public memory. You have to make a conscious effort to recall the time when the Labour Party was exciting, heavyweight, sexy. What excited so many of the intelligentsia and brought them into the Labour Party was the rigor of Tony's argument for greater equality. He wasn't proposing a gray egalitarianism that would free individuals from gross injustice only to lock them into bureaucracy." She laughs. "He was all for us having a healthy trace of the anarchist and libertarian, and not too much of the prig and the prude."

The high point came in 1976, when Crosland was made foreign secretary. ' ' Henry Kissinger was, of course, the secretary of state, and just embarking on the shuttle diplomacy with southern Africa. He made a detour to London in his specially fitted plane, imagining the new British foreign secretary would be happy to drive to Heathrow and join him for a talk. Instead he was told that the foreign secretary was busy in his Grimsby constituency—hundreds of miles away in a hinterland, so far as Henry was con-

cerned." Kissinger was forced to change planes and fly to an R. A.F. field near Grimsby. Susan Crosland smiles at the initial reactions of the two men. "At the meeting, Tony was taken by Henry's intellect and humor. The feeling wasn't mutual.

"Nor was it mutual when they next sat beside each other, at an O.E.C.D. meeting in Luxembourg. 'Tony absolutely refused to go along with convention,'

Henry told me later. 'Meetings are meant to be of two hours' duration. Each time a minister repeated himself, Tony said, "We've already heard that; let's move on to the next point." The meeting was over in half an hour. He treated me with great respect—that is to say, with less disdain than he treated the others. I thought of him as a colossal pain in the neck.' 'I may fall in love with Henry,' Tony told me when he got back from Luxembourg.

"I forget when the love affair became mutual—what Henry described as a unique relationship between foreign ministers: 'We got along, not because we agreed or disagreed, but because we were on the same wavelength, two odd-

"You have to make a conscious effort to recall the time when the Labour Party was exciting, heavyweight, sexy."

balls intellectually interested in problems not just because we were foreign ministers.' "

For a moment, the bluegreen eyes look off. ' 'Tony and I were to visit President Carter early in 1977. Just before we were to fly to Washington, Tony died."

Crosland was struck down in almost unbearably poignant circumstances while still at the height of his powers. Ten months after he became foreign secretary, he and Susan had a first weekend to themselves. She was writing in the same room where he was working on his papers, when he said, "Something has happened." As she turned in her chair, he said, "I can't feel my right side." After a massive brain hemorrhage, he lay in a coma for six days, with Susan lying by his side. The description of these events in her biography of him must be one of the most harrowing sequences in modem literature.

"When Henry and Nancy Kissinger came to see me in London afterwards," Susan resumes, "and learned I'd be going to see my sister in Washington in May, they said I must come to a small birthday dinner the British ambassador

was giving for Henry. I said I wasn't going—I led a very withdrawn life for a long time. Henry said it would just be a family affair. It was the strangest birthday party I have ever attended. Three people's lives had altered dramatically since we had all dined at the British Embassy in Washington with the Queen ten months earlier. Kissinger was now out of office. Tony was dead. And the British ambassador had learned earlier in the day that he had been sacked by the new British foreign secretary."

It took her six years to return to normal life, three and a half of them spent writing the biography. She refers to those six years as "gray" years. "It wasn't until I finally returned to the world of the living that I discovered colors can be drained by one's state of mind. Driving along a country road past a hill of trees I had seen a thousand times during those six years, I thought, What fantastic colors— and realized that throughout those years the trees had been gray."

Asked about the effect of the Tory years under Margaret Thatcher, Crosland says, "Margaret Thatcher hit a populist chord with a lot of her policies, and the Labour Party has had to accept that a number of them—trade-union reform, people being able to buy the council houses they have rented from the state—are here to stay. So Labour has had difficulty in asserting boldly how its values differ from those of the Tories. The result has been a kind of fluffiness in British politics—which God knows you didn't have under Thatcher—and too many Britons have been left with the uninspiring feeling that they might as well vote for the party that 'does the most for me,' as if one were deciding which is the most competent accountant."

So far, however, she hasn't considered transplanting herself back to the United States. "I love going back to visit my family. But I also love the independence you have in another country. And in the present climate in America, I think I should go mad with all the political correctness."

his gloomy view of her home country is not reflected in Dangerous Games, in which leading politicians on both sides of the Atlantic are flawed, to say the least. "Yes," she says, "but it is only the sinister Washington lobbyist and his beguiling young sidekick who are totally amoral. Actually, I developed a soft spot for both of them. However awful Jock is, he has an extraordinary vitality, and he's funny. I can excuse a lot if the person is funny enough. And the amoral Lisa is gutsy: her calculating deceitfulness is the only way she knows to pull herself up in the world. But I didn't want her to win in the end."

Each of Susan's novels has produced guessing games: Whom are the characters based on in real life?

"Groan. O.K., a lot of the characters are inspired by real politicians and real media people I know. But then my fantasy takes over. The trouble is, nobody quite believes me when I say it is fantasy, because the worlds I describe—how power brokers in Washington, New York, and London behave behind the scenes—are the worlds I know intimately."

In an interview with Rosemary Carpenter, of the London Daily Express, when her first novel came out, in April 1989, Susan Crosland produced one explanation for why she has not married again. No one could ever replace Tony, she said. Hence her separate compartments.

Carpenter concluded, politely enough, that there can't be many men who wouldn't be pleased to fill one of these compartments, and no doubt she is right. But the interview had started on a slightly more puzzled note, as befits a young reporter approaching a senior figure of the British left.

"Susan Crosland is a truly sensual woman. She has just written a very raunchy novel set in Fleet Street and in Westminster, and the sex scenes, of which there are many, are arousing and adroit. . . . Susan Crosland is discreet, but one gets the impression that she is writing as much from her own sexual experience as from imagination."

I tremble to think this may be the case with her latest novel, Dangerous Games, which contains descriptions of several situations—handjobs in the office and the like—in which no friend would like to imagine her. If we analyze what makes Susan Crosland a successful practitioner in a crowded profession, the first quality that shines through is that she is a brilliant storyteller. Whether from narrative tension, sexual tension, or involvement with the characters, she makes us want to keep turning the pages. It is comparatively unimportant that, when she writes about presidents, monarchs, secretaries of state, and the rest of them, she knows the people she is writing about. The other important ingredient is her charm, her enjoyment of life, and, yes, let us face it, her wonderfully sporting attitude to sex.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now