Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Most Underrated Writer in America

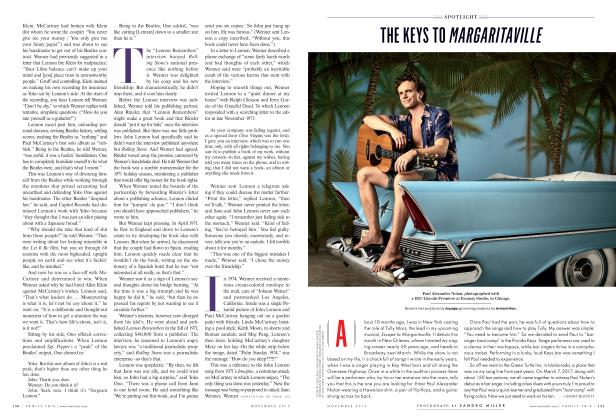

Louis Auchincloss leads a sort of double life. By day he's a Wall Street lawyer. Otherwise—like Wallace Stevens the insurance man, like E. B. White the farmer—he's a writer, whose twenty-second novel is just out. What's more, says SUSAN CHEEVER, "he is the only serious novelist writing about the rich and powerful from the vantage point of the rich and powerful"

Louis Auchincloss is never mentioned in lists of great American writers. He has won no important prizes and earned no Ivy League honorary degrees. Although many of his early novels were best-sellers, his most recent books have not been bought by the book clubs or sold to paperback houses, and he is generally reviewed with low-key deference as an observer of a narrow segment of New York society.

This is strange, because Louis Auchincloss is one of the best writers alive. He has probed the American character more boldly and more intelligently than many of his more celebrated contemporaries, and he is the only serious novelist writing about the rich and powerful from the vantage point of the rich and powerful. "Those who should be most in [his] debt have no idea what a useful service he renders us by revealing and, in some ways, by betraying his class," Gore Vidal, whose mother was married to Auchincloss's father's cousin, has written. "Almost alone among our writers he is able to show in a convincing way men at work... creating the American empire." Although Auchincloss writes primarily about upperclass life (as did Tolstoy, Proust, and Henry James), he has created an astonishingly wide range of characters, and he is one of a handful of male writers whose sympathy for women is so extraordinary that his female characters are as complete and convincing as his men. He writes about money, crime, sex, adultery, and ambition in a prose so deft, so elegant and clear, that it's often only after you finish an Auchincloss novel that you think about it—before that you've been caught up in the pleasure of reading it. He is also one of our few real men of letters: his work includes scholarly essays, criticism, plays, and biography as well as fiction.

So why has Louis Auchincloss failed to get the recognition he so clearly deserves? Do critics and readers secretly resent the rich, established upper class? Or is he dismissed because he fails to conform to the stereotype of what an American writer should be? Writing is supposed to hurt, damn it! We expect our writers to be passionate megalomaniacs, drained and agonized by their work, flamboyantly self-destructive, pouring their whole heart and soul into writing until they finally bum out, in one last long, pathetic, drunken gurgle. It looks as though we've never gotten over Hemingway.

Louis Auchincloss is not like that at all. A storybook aristocrat, he is the son of a wealthy corporate lawyer who married the socialite cousin of his Yale classmate Courtlandt Dixon. (Many of Auchincloss's friends and family have names composed of two last names.) As a youth Louis marched with the Knickerbocker Greys, attended Mrs. Hubbell's dancing class at the Colony Club, and went to Groton and later to Yale. At sixty-eight, tall and trim, with the hawk nose and receding chin that seem to be the genetic inheritance of the Wasp prince, he is a major figure in what's left of New York society, a society where discretion is still the first rule of manners. A serious clubman (the Century Association in midtown, the Down Town Association downtown), he is also president of the Museum of the City of New York. He is a witty and conscientious dinner guest who always turns to talk with the woman on his other side when the roast is served and who never drinks too much. Since 1954 he has practiced trusts and estates law at the Wall Street firm of Hawkins, Delafield &

Wood. (Trusts and estates law is a personal, relatively leisurely branch of the legal profession. It involves dealing with clients, often wealthy clients, and decisions which will affect their private lives. Auchincloss is superb at this.) A passionate Francophile, he is as erudite as he is privileged; this is a man who daydreams about the court at Versailles.

Everyone who is anyone is Auchincloss's cousin or classmate, or cousin's classmate or classmate's cousin. His wife, Adele, is a descendant of Commodore Vanderbilt. An artist, she also serves as a trustee of the Natural Resources Defense Council, the New York Botanical Garden, and the Central Park Conservancy. The 1890s journal of Adele's grandmother Florence Adele Sloane, titled Maverick in Mauve, was recently published by Doubleday, with a long introduction by Auchincloss; the editor was Jacqueline Onassis, another Auchincloss relative. (The Sloanes made their money in furniture, and Auchincloss calls their story "From rugs to riches.")

The Auchinclosses have lived for twenty-six years in the comfortable post-Victorian clutter of the big old apartment on upper Park Avenue where they raised their three sons: John Winthrop, now a lawyer in Washington, D.C.; Blake, currently in Europe studying architecture; and Andrew, a student at Yale. The living-room bookcases hold Auchincloss's books bound in leather, and the room is filled with bits of Auchinclossiana. In the window, sculptures of young girls by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (Adele's grandmother's first cousin) flank a bust of Louis Auchincloss's mother by the interior decorator Dorothy Draper. On the walls hang small portraits of Auchincloss favorites Edith Wharton and Samuel Richardson and a big oil of Auchincloss's greatgrandfather Charles Handy Russell painted by William Sidney Mount. The Auchinclosses weekend at their country house in Bedford and travel to Europe in the summer. Although he works five days a week in his law office—traveling from uptown on the subway—Auchincloss produces a book a year in his free time. His life is thoroughly organized, thoroughly conventional, thoroughly satisfactory. It makes terrible copy.

Most of Auchincloss's models are not famous; they come from a stratum of New York society above celebrity, from the class of people who think of publicity as something to be avoided.

This wasn't always so, of course. Auchincloss had to wrestle with his demons, and with his parents, to win acceptance for the idea that a man of his background could be a writer. Coming to terms with being a man and taking his place in the world of men was a long, painful process, and the conflict between hard-nosed workaday masculine values and the more compassionate, playful feminine values has shaped his character and given form to his work. Bom into a society where morals were firmly based on religion, Auchincloss has seen the subversion of the old-fashioned code that once seemed permanent, even sacred. "The ruling class here used to emulate the old aristocracies in Europe, which had a strong moral basis," he says to me as we lunch in the hallowed male purlieus of the Down Town Association. His

haughty manner and relentless upper-class accent are relieved by his self-mocking tone and the high cackle of amusement which punctuates his conversation. "Look at the houses they built! Chateaux and Tudor manors, and they sent their daughters off to Europe to marry dukes. Now that's eroded altogether and there's really no moral basis. Although an awful lot of the immorality that goes on went on in the past, one of the differences is the lack of hypocrisy today. The loss of morality is not even denied, and is that a good thing? Maybe the hypocrisy was some kind of protection. I think we're going to come to long for Victorian hypocrisy. People are so brazen-now. At least the Victorians bothered to wear a shirt!"

When Auchincloss was a little boy, his adored father took him downtown on an outing to Wall Street. "Never shall I forget the horror inspired in me by those dark narrow streets and those tall sooty towers and by Trinity Church blocking the horizon with its black spire—a grim phallic symbol," he recalls in A Writer's Capital, his candid memoir of his first thirty-seven years and one of the best books ever written about being a writer.

"I thought everything in that world was perfectly revolting," he says, sitting behind his desk in the comer office at Hawkins, Delafield & Wood. The office is hung with French marriage contracts from the reigns of Louis XIV, XV, and XVI; on one is the spidery little signature of Marie Antoinette. A glass-fronted bookcase holds some of Auchincloss's extensive collection of first editions; on top of the case is a framed portrait of Adele with their first child, and across the room is a glass-topped table covered with family photographs—John and Louis in France, Andrew perched on rocks in Wyoming. ''The women had all the fun. I didn't see that men had any fun at all. They had those awful sports. I didn't like golf and I didn't like tennis much and I didn't like any kind of ball throwing. Their business seemed so boring." In Auchincloss's emphatic, elegant accents, the phrases sound like this: Everything in that world was PERfectly reVOLTing. The WOMen had all the FUN. Those AWWWWful sports. Their business seemed so BORRRRing. ''When Father talked to his partners, I couldn't get out of the room fast enough. Mother and her friends had a lovely time; they read books and went to matinees and traveled. They were always laughing. I didn't know any men who did any writing whatsoever; that was a feminine thing." The conflict was not simplified by his father's instability. Joseph Howland Auchincloss was taken out of Groton and later law school by episodes which culminated in serious nervous breakdowns when he was in his fifties.

At Groton the battle was joined. Louis's mother had taught him to tell the truth, and when he and two other boys were questioned about a prank—they had thrown a stone at a train—Louis quickly confessed and named his associates. This was a breach of the fierce schoolboy honor code, and he was branded a snitcher and tormented and shunned by his schoolmates. Terrible in sports, bored and snooty, he was an abject failure as a Grotonian. Eventually he realized that academic excellence would win him respect and protection if not popularity. He describes the process in A Writer's Capital.

For the next three years marks were everything to me. I sought permission to rise before the waking bell so that I could study. I would fib outrageously, and without a qualm... stating... that I had done the required sports and then hide away on winter afternoons to do my Latin or mathematics. My marks rose steadily, astoundingly. I moved into all "A" divisions... .1 became first in my form.

Needless to say, my parents were soon alarmed. They saw that the cure threatened to be worse than the disease. Mother actually offered me a money bribe to drop my average. Could anything, I thought indignantly as I spumed her lure, more clearly prove that women, the privileged class, did not even understand the conditions of the workers? Not since Marie Antoinette had directed the poor to the patisserie had there been such evidence of female frivolity in the presence of serious things.

•When Auchincloss graduated from Groton in 1935, he won almost every academic prize the school had to bestow.

It was at Yale, where he was an editor of the Yale Lit, that he decided, after much deliberation, to try writing a novel.

The result was a four-hundredpage drama of love, suicide, and prep-school life modeled on Madame Bovary. His parents, to whom he showed it immediately, were appalled. His mother was afraid it would offend friends and family, and she was not reconciled to the idea of her son as a writer of romances; his father felt that such frivolous doings might well damage Louis's future, inevitable Wall Street career. Convinced of his genius, Auchincloss sent the manuscript off to Scribners anyway. Scribners rejected it. ''And then my life simply fell to pieces," he remembers in A Writer's Capital. "I was not indignant at Scribner's. I was not even surprised... .What in the name of all that was holy... [was] I up to... dabbling in literature, rushing around to every play on Broadway, dreaming of teaching, and, worst of all, writing a novel, when all the while I knew that my real destiny, my serious destiny, my destiny as a man, was to become a lawyer and submit to the same yoke to which my poor father had so long and patiently submitted?"

In a hysterical renunciation of his literary folly, Auchincloss quit Yale after three years and enrolled in the University of Virginia School of Law, the best school that would take him without a degree.

To his amazement, and his great good fortune, he found that he loved law school. The cases were fascinating studies of human behavior, and he was thrilled by the majestic clarity of the great judges' written decisions. In 1941 he secured a position in the prestigious firm of Sullivan & Cromwell, but as the United States entered the war he realized he would be drafted if he didn't enlist, so he applied for a commission in naval intelligence. He served in the Panama Canal Zone, took part in the Normandy landings as an executive officer of an L.S.T., and wound up as commander of an L.S.T. in the Pacific. Not until he was safely back at Sullivan & Cromwell, however, did he dare submit another manuscript—his third novel—to another publisher. Prentice-Hall agreed to publish The Indifferent Children in May of 1947. Auchincloss was delighted; his parents were horrified. He was twenty-nine years old, a graduate of law school, and a war veteran, but Mother and Father were still a critical influence; he was living in their big apartment at 66 East Seventy-ninth Street. A compromise was reached. He agreed to publish his book under a pseudonym. Angrily he chose the name Andrew Lee—an ancestor of his mother's who was said to have cursed any of his descendants who drank or smoked. It took five or more years of struggle, with his parents and his own doubts, and the writing of two books under his own name, The Injustice Collectors and Sybil, before Auchincloss decided to leave the practice of law for a while and write fulltime. His parents gave in and offered to support him financially. He moved out of their apartment and into his own bachelor quarters at 24 East Eighty-fourth Street.

(Continued on page 119)

(Continued from page 107)

During the two years he spent writing exclusively, he wrote two more books, A Law for the Lion and The Romantic Egoists. But the most important event of his sabbatical was going into formal analysis with Dr. John Cotton, head of the Department of Psychiatry at St. Luke's, himself possessed of a long pioneering American lineage. Psychoanalysis was a turning point for Auchincloss. It ended his frantic search for a personal and a professional identity he could live with. He returned to the law. He got married. Since then he has combined his two careers and the two sides of his nature with incomparable success. "A great step was taken when I ceased to think of myself as a 'lawyer' or a 'writer,' " he says. "I simply was doing what I was doing when I did it." In 1956 Auchincloss met his future wife, Adele Lawrence, at a dinner party in her parents' apartment. He and the senior Lawrences were active members of the Thursday Evening Club, a group of New York society families who met regularly for lectures and musicales with a view to broadening their cultural prospects. In 1959 he and Adele moved to their present apartment on Park Avenue. "After that," Auchincloss says, "things have been more or less in a groove."

It's a groove that might exhaust a less organized, less energetic man. Each Auchincloss work or article in progress is neatly stashed in a manila folder, and for thirty years he has kept complete scrapbooks of his career—every review, every story, every notice of a lecture or reading.

He writes on weekends in Bedford while Adele gardens, or after hours at the office, or in the evening at home, or wherever he happens to be. Using a No. 2 pencil, he works on oversize yellow legal pads propped on a lapboard, or on his knees, or on whatever is handy. "The special conditions some writers require are luxuries," he says. "I've learned to stop and pick it up. Have you ever seen an opera singer rehearse? Now, if I were singing Alfredo's aria 'De' miei bollenti spiriti' and I stopped, I'd have to go back to the beginning! But they pick it up at the exact note."

In 1964, ten years after he returned to practicing law, Auchincloss wrote his ninth novel, the one he thinks is his best, The Rector of Justin. A powerful story about a boys' prep school and its founder and headmaster, Dr. Francis Prescott, the book deals with the consequences of an idealism based on illusion. To write it, Auchincloss read every privately printed biography of great headmasters that he could find, and drew heavily on his memories of Groton and its indomitable founder, Endicott Peabody. Groton was an extraordinary school: Auchincloss's class produced a secretary of the army, an assistant secretary of state, ambassadors to the Philippines and Indonesia, a novelist, a Benedictine monk, a covey of successful doctors and lawyers, and presidents of the First National City Bank, the Mellon Bank, and the Celanese Corporation. But Peabody, for all his grandeur, was too simple a man for Auchincloss's hero; to create Prescott's character, he drew on his New York friend Judge Learned Hand, the chief judge of the Second Circuit of the Federal Court of Appeals and one of the foremost jurists of the twentieth centuiy. Auchincloss is one of a handful of fiction writers with the confidence to discuss their sources. His characters are sometimes taken directly from life, but more often they are made up of bits and pieces of people he knows—and doesn't hesitate to identify. Most of Auchincloss's models are not famous people; they come from a stratum of New York society above celebrity, from the class of people who still think of publicity as something to be avoided, and who watch television, if they watch it at all, on black-and-white nine-inch screens. Besides Judge Hand, Auchincloss has based characters on his grandmother, fellow lawyers, and Aileen Tone, who was secretary and companion to Henry Adams. Although he's often been compared to Henry James and Edith Wharton, the primary literary influences on him have been the nineteenth-century French novelists—Stendhal, Flaubert, and the Goncourts. The novel that has had the most profound effect on him, a book he knows almost by heart and from which he drew the plot and characters for his own novel A World of Profit, is the Goncourts' Renee Mauperin, an obscure classic about a French bourgeois family in which the price of social climbing is a lingering death.

Honorable Men, his twenty-second novel, which Houghton Mifflin has just published, is the first contemporary novel he has written since The House of the Prophet, which was based on the life of Walter Lippmann. Honorable Men is vintage Auchincloss, but the writing is leaner and meaner than in his other recent novels. There is less furniture and more action. "The book is different in that the two protagonists are more completely imagined, more completely created than my other characters," Auchincloss says. "I thought I was going to give some idea of how the Vietnam War had come to be. I used to tell my father that if my friends at Yale ran the country there wouldn't be any trouble, and they did run the country!" He laughs. I laugh. There was trouble. When Auchincloss finished the book, he despaired. He had not done what he had set out to do, and he considered abandoning it. A few days later he reread it and felt a tremendous relief. It wasn't what he had planned, but it was good. "I don't know what this book is," he says, "but it stands on its own two feet."

The novel's principal character is Charles "Chip" Benedict, the handsome scion of a Wasp glass-manufacturing family who eventually becomes special assistant to the secretary of state during the Vietnam War. Benedict marries Alida Struthers, a witty but not wealthy beauty who, on a lark, has become debutante of the year—seducing her away from the rich wimp to whom she is engaged. The other major figures are Gerry Hastings, the embodiment of naval masculinity, who is Benedict's commander on an L.S.T. during World War II, and the androgynous Chessy Bogart, a charming, self-confident scholarship boy whose brash seduction of Benedict one night in their dormitory at prep school reverberates through the book. Embedded in the story are the old Auchincloss themes. What has happened to morality without religion? What is a man, and what does he have to do to prove it in our society? Ironically, Benedict betrays his manhood in loving his friend Chessy and confirms it by destroying him. The massacres committed by American soldiers in Vietnam—that ultimate perversion of the masculine ethic—finally seem to humanize Benedict. Although Chessy and Alida are right in their assessment of Benedict as cold and inhuman, lightest of all is his mother. "From the very beginning, I could see that you were snuggling with yourself," she tells him near the end of the book, "and I was always afraid that you were snuggling with something bad in yourself. That was the puritan in me. A struggle had to be like that huge George Barnard statue they used to have in the main hall of the Metropolitan and that now, I think, is in the cellar. It represents the two natures of man, one good and one evil, wrestling with each other. What I couldn't see.. .was that a child might be simply snuggling to be himself." In a world without religion, Mrs. Benedict has seen that she and her son are moral leftovers, people cleaving to codes of behavior that have lost their foundation. "[Your father] told me once," Mrs. Benedict says, " 'You and Chip have a lot in common. You're both puritans without a god.' "

These days Louis Auchincloss seems supremely at home in the world. His sons are grown, his work is expanding, and at the end of next year he will reach mandatory-retirement age. His law career will be over, and he is looking forward to writing full-time again. Even the discrepancy between his critical reputation and the quality of his work doesn't bother him so much anymore, he says. "The critics' saying that I have a narrow focus used to make me so cross, but now I've gotten used to it." Perhaps he'll be recognized posthumously, this dedicated writer who has told us so much about ourselves. The narrowness of his focus is a false issue, and he knows it. Like all the great novelists, he has written about the human heart, the conflict between desire and morality, the mles people make for themselves, and the way they live out their lives. If the critics and the literary establishment don't get it, he's not going to make a fuss. It doesn't matter. As long as he can keep on writing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now