Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Erotic Art of D.H. Lawrence

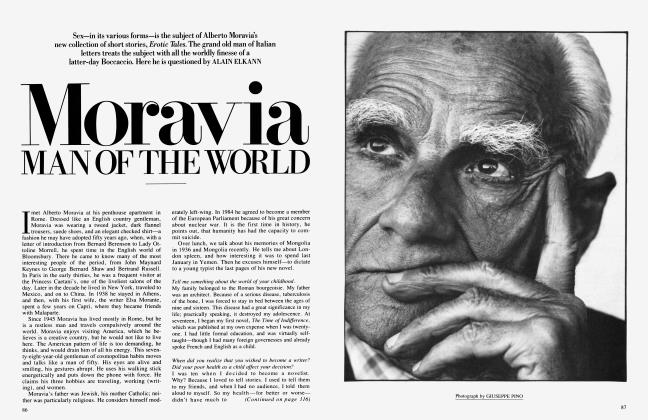

In his final years, D. H. Lawrence painted. Like his writing, the pictures present sexual encounters between big Germanic women and small but passionate men. Now scattered, many were once assembled by his widow, Frieda, at their Taos, New Mexico, ranch—where STEPHEN SPENDER saw them in 1947

In the summer of 1947 my wife and I went on a tour of the American Southwest. In Taos we met Frieda Lawrence, the widow of D. H. Lawrence; Dorothy Brett, the eccentric English painter; and Mabel Dodge Luhan, the philanthropist and author, with her American Indian husband, Tony Luhan. It was Mabel who in 1922 had enticed the Lawrences to Taos with tales of the dark instinctual life among the Indians, and of their tribal dances.

Frieda, who has been much criticized, was, whatever her faults, most generous and warmhearted. When I told her that after my wife returned to England I intended to stay on alone in America to write my autobiography, she at once offered me the loan of her ranch.

Situated above Taos at 8,600 feet, in the Sangre de Cristo mountain range, which the Indians regarded as sacred, the ranch had been given to Frieda by Mabel Dodge. (In return, Frieda had presented her with the manuscript of Lawrence's third novel, Sons and Lovers, about his adolescence in Nottingham.) Lawrence resided there, his health failing from tuberculosis, between 1922 and 1925, when he returned to Europe. He died five years later.

I stayed at the ranch through August and September, breathing the pure rarefied air which made my heart beat faster. The place was indeed so sensationally lonely that, paradoxically, solitude here became a kind of throbbing presence which one lived with. I worked all day, getting up with a sun that seemed to cleave the sky at dawn with a white steel ax whose blade hung there hard and brilliant the whole day. Then, suddenly, there were shadows, and I went to bed with the approach of night. Two or three times a week two young friends of Frieda's, sometimes accompanied by Frieda herself, would bring me supplies, mostly cans of Campbell's soups, of which I became a connoisseur.

Everything here reminded me of Lawrence: the little memorial chapel, looking very handmade, with its rather primitive mosaics done after Dorothy Brett's designs; the altar, allegedly containing his ashes; still more, inside the main house, which had been built after Lawrence's death, his and Frieda's books on the shelves. Near the house was the simple cabin where Lawrence had lived during his stay, and one could imagine him, sandy-haired, light-blue-eyed, stepping in through the door, having just milked Susan, the cow. Or, outside, where there was a little plateau, with its trees, and the immense view of the desert below, he might be watching a chipmunk, or be inspired to write a poem, entranced by a snake sliding toward the water trough.

But what made his presence most insistent were, hanging in the house, several of his paintings, aggressive as banners. They were all hot flesh and flaming or black hair—crude figures in crude landscapes of the Tuscan countryside near Florence, where Lawrence had painted them between 1926 and 1928. As pictures, they were amateurish, but they spoke out louder and clearer than most English paintings of the time. Among other things, they were protests against English good taste and politeness. The women in them were for the most part large—on the Briinnhilde scale of Frieda Lawrence—and had round, sagging breasts. The men were slender but muscular, hirsute and with beards or mustaches. Some of them crouched in postures which gave them a kind of haunchiness. There was a lot of swinging, pendulous love-dancing. Lawrence obviously loved painting the sexual organs—of men as well as women—complete with pubic hair. For some reason, in England at this time it was considered indecent to paint the pubic hair of female nudes. As late as 1930 an English painter friend of mine who happened to come from a wealthy family was cut off by his father for painting the pubic hair of a nude female model.

The sexuality in Lawrence's paintings is really no more exaggerated than that in Titian, or Michelangelo, or Rubens. In fact, Lawrence's pictures look impoverished in their view of sex when compared with those of the Italian and Flemish painters. This may be because he paints sexuality without procreativeness. There are no bambini. His seems a world of copulation without children. In this he looks back, as he does sometimes in his poetry, to centaurs, satyrs, bacchantes—the pagan Greek or Roman past. But he also draws on his childhood memories of the English miners with whom he was brought up—his own father squatting naked in the bathtub of their front parlor.

When, in 1960, there was the famous trial for obscenity of Lady Chatterley's Lover, which Lawrence had written at the same time as he was painting these pictures, the case was often referred to as "the trial of Lady Chatterley"—as though the novel's heroine herself were on trial. By a similar association I found myself looking at the pictures in the ranch as though the men and women in them had been put on trial for obscenity or indecent exposure, for I remembered very well the lawsuit brought in London in 1929 against the Warren Gallery, where they were exhibited, on the plea of a "common informer," who denounced them as obscene. On the instructions of a magistrate named Mead (probably remembered today only for that action), two detectives and six policemen marched into the gallery and took down certain pictures from the walls. For good measure, they also seized some of William Blake's drawings.

There was a tremendous scandal, and many distinguished people (Lytton Strachey, Roger Fry, Leonard Woolf, Virginia Woolf, Jacob Epstein, and others) signed a protest supporting Lawrence. Artists and writers probably prefer persecution to neglect— though Lawrence, who had suffered from censorship ever since the banning of his early novel The Rainbow, had probably had too much of it. Besides, he was now a very sick man. But some squibs he wrote directed against the English attitude toward his pictures show Lawrence enjoying himself, feeling that he is on the side of the young against institutionalized respectability. For example:

"GROSS, COARSE, HIDEOUS" (Police description of my pictures)

Lately I saw a sight most quaint: London's lily-like policemen faint in virgin outrage as they viewed the nudity of a Lawrence nude!

There were several more of this kind. Pornography is notoriously difficult to define, but in the days when there were very strict laws against it, the idea seemed to be that a work of art was pornographic if it aroused feelings of sexual excitement in the beholder. On these grounds Auden always said that Lady Chatterley was indeed pornographic, since he found that reading certain passages of it gave him an erection. (I would agree that they do have this effect.) He told me that if he had been called upon as a witness in the Lady Chatter ley case he would have said it was pornographic.

But the question of whether Lawrence's work was sexually arousing to the reader or the beholder is really irrelevant. What Lawrence believed was that art—whether fiction, poetry, or visual representation—-could excite the reader or beholder in ways that were either life-enhancing or lifedegrading, sick and corrupt. The distinction was as clear to him as that between living and dying—and, of course, as a consumptive (in an age when tuberculosis usually proved fatal) he knew a great deal about both. For him, the artist had to choose to be on the side of the living; and most of his contemporaries seemed on the side of death and corruption. When he considered that the wrong choice had been made, Lawrence was as puritanical and censorious in his attitude to his contemporaries as were those who censored him. According to Lawrence, the supreme crime was "doing dirt on sex." And, given the chance, he would certainly have censored the works of James Joyce, whom he believed to do this.

Always opinionated, he accompanied his pictures with a flood of words. For his volume of reproductions he wrote an essay, "Introduction to These Paintings." It contains a section on Cezanne which Kenneth Clark told me he thought to be the best criticism ever written on Cezanne. Inevitably Lawrence saw the history of modem European art as the history of the modem artist's fear of the human body. But it was the Romantic poets above all— Keats, Shelley, the Brontes—who tried to sublimate the body out of existence in what Lawrence calls their "postmortem" art, and so with the Victorian and Pre-Raphaelite painters. All this is rather predictable, but what is good about Lawrence is the marvelous flashes of interpretation in which he forgets his own theories. For instance, he writes: "Probably the most joyous moment in the whole history of painting was the moment when the incipient impressionists discovered light, and with it, colour." Of course, he then goes on to say that the Impressionists were afraid of the body.

Cezanne is seen as the great modem artist who returns to the realities of the sensual world, principally through his paintings of apples: "After a fight tooth-and-nail for forty years, he did succeed in knowing an apple, fully. . . .That was all he achieved. . . .The conflict, as usual, was not between the artist and his medium, but between the artist's mind and the artist's intuition and instinct." Cezanne, "with his apple. . .did shove the stone from the door of the tomb." Wryly appealing to the reader to join in this enterprise, he writes: "We, dear reader. . .we were bom corpses, and we are corpses."

Poor Lawrence was himself almost a corpse when he painted these pictures. Looking at them, I wondered whether their theme was not the yeamed-for resurrection of his own body. Perhaps the act of painting was itself the resurrection, for in painting them the writer escaped from the tedium of writing, publishing, controversy (that is, until the Warren

Gallery show). One day in October 1926, when the Lawrences were living at the Villa Mirenda, in Scandicci, near Florence, and happened to be painting some doors and windows, Maria Huxley (Aldous's wife) turned up with four rather large canvases an amateur artist had left with her. One of them, painted over a mud-gray background, showed "the beginnings of a red-haired man." Lawrence took the paints he was working with and immediately started to transform this "grimy and ugly beginning" into something of his own. "So for sheer fun of covering a surface and obliterating that mudgrey, I sat on the floor with the canvas propped against a chair—and with my house-paint brushes and colours in little casseroles, I disappeared into that canvas."

Disappeared—to be reborn again. Lawrence's paintings express the enjoyment he felt painting them; they grope toward a vision of an earthly paradise, before the Fall, in which everyone is free to disport his or her self.

At the ranch there was one picture which particularly fascinated me, an illustration for a story of Boccaccio's about some nuns who come out of their convent into the garden and peer at the sex of the convent gardener, who, sleeping under a tree at midday, has the smock of his gardener's costume lifted by the wind, revealing his nakedness. The peering figures of the nuns form a jagged semicircle, and the legs of the gardener are like those of a compass. There is an attempt here to make a pattern which moves beyond the subject of the picture and which evokes a world of pure painting, free of Lawrence's genital obsessions, though starting out from them.

After all, Lawrence might have been a painter.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now