Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

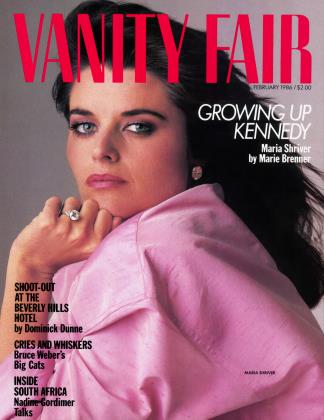

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowINSIDE SOUTH AFRICA

This morning I learn that one more black man has been hanged in South Africa; this one was a poet, Benjamin Moloise. At noon my radio will report shops looted, whites attacked, cars burned. This evening, my television will flash pictures of every white man's nightmare—police firing shotguns at blacks marching on white suburbs, killing black children who'll be buried as martyrs, seeding endless generations of replacements. The reporter will inevitably say, South Africa is in flames. Then I'll turn off the set and the flames will die until tomorrow.

A year ago, I visited South Africa. A white middle-class Midwesterner, fresh from college, writing a first novel, I imagined South Africa as a testing ground—an embattled land confronting one of the most explosive dilemmas of our time. I spent seven months driving across the country, seeking out ostrich farmers, revolutionaries, Communists— anyone, black or white, who would talk. My most rewarding days were spent with writers.

Though ruled for nearly forty years by one of the most hated regimes in modern times—one that has placed all but intolerable pressure on dissenters—South Africa, has not produced an influential literature of white exiles in Paris, London, or New York. Instead, extraordinary work—fiction, plays, and poetry—has been written inside South Africa by] white writers who remain in their beautiful, tormented land,, fighting the enemy at close range. Some are bomb-planting revolutionaries; others settle for the quiet but inexorable language of revolt.

Novelist Nadine Gordimer and poet Jeremy Cronin were both born into South Africa's "big white country club'—the 5 million whites who rule 24 million blacks. Instead of seeking a safe literary exile, both have stayed inside their benighted country. And they corresponded when Cronin spent seven years inside maximum-security prisons. DANIEL VOLL interviwed them in Jo'burg and Cape Town

Nadine Gordimer—sixty-two, the author of sixteen books—is South Africa's major international literary voice and an unrelenting critic of the white regime. Jeremy Cronin, thirty-six, is an important new voice in South African poetry. He has spent seven years in prison for supporting black revolution. His award-winning collection of poems, Inside, was published after his release. Both writers remain in South Africa, continuing the fierce logic of their battle against government tyranny.

The day I visited Nadine Gordimer in her quiet, sylvan neighborhood in Johannesburg, the black townships that ring the city were in flames. Police, moving in with tear gas and rubber bullets, were calling it a "revolutionary situation." It was the start of the bloodiest year in South Africa since 1976, when hundreds of black children were killed by government forces in Soweto, the notorious township ten miles from Gordimer's home.

The two-story house sits behind a high white wall on a street lined with lavender-petaled jacarandas. I was escorted from the front gate by a gardener, who showed me past neat flower beds to the house, where Gordimer's husband, a cordial man trailing a glossy hunting dog, ushered me into a museum-size front room. Bookshelves lined one wall, art magazines lay on small tables, steady winter light streamed through tall windows. It seemed an eerily perfect place from which to bear witness to the final years of a dying white order. When Gordimer entered smiling, in taupe cords and a sweater, I was surprised: I had prepared for a rapt bird. (Alan Paton, author of Cry, the Beloved Country, told me that when he wrote Gordimer that her novel Burger's Daughter "expressed warmth," she responded, "It is not warmth that makes a good novel.") But I find her lithe and hospitable, with the dark, intent eyes of an affable llama. Before starting the interview, I present her with a gift—a Polaroid of Eudora Welty celebrating her seventy-fifth birthday at Bill's Burger House in Jackson, Mississippi (a friend has sent me the picture). "Goodness," Gordimer says, "I first went to see Eudora in Jackson back in 1959. I've always admired her work. You know. I've just finished that book on her childhood." Standing near the window, Gordimer reads the inscription on the cake: "God Bless America and Eudora on Her 75th Birthday." Then, eyebrows arched in elegant reproach, she says, "I would have put Eudora first."

Gordimer serves tea, then perches in her chair, knees hugged to her chin, and talks about the similarities between growing up in the old American South and in South Africa. "There was some kind of relationship—there still is—between white people and black people in the South that doesn't exist in New York even today. Many of my friends in New York, they just don't know any black people." She takes a quick breath, then states firmly, "But I don't think that's important. I think it's much more important for people to have their rights than to have white friends."

Such talk about rights is not just easy talk. Not here in South Africa, where the white Nationalist regime has promised to use whatever force necessary to keep 24 million blacks from sharing equal political and cultural rights with the country's 5 million whites. So far that promise has been kept with brutal efficiency: the morning of my meeting with Gordimer, three more blacks died in clashes with government forces near a small gold-mining town thirty miles away, where as a young girl Gordimer wrote her first stories.

TWO POEMS FROM JEREMY CRONIN'S VOLUME, INSIDE

FOR COMRADES IN SOLITARY CONFINEMENT

Every time they cage a bird the sky shrinks. A little.

Where without appetite— you commune

with the stale bread of yourself, pacing to and fro, to shun, one driven step on ahead of the conversationist who lurks in your head.

You are an eyeball

you are many eyes

hauled to high windows

to glimpse, dopplered by mesh

how-how-how long?

the visible, invisible, visible

across the sky

the question mark—one

sole ibis flies.

A STEP AWAY FROM THEM

There's a poem called that by Frank O'Hara, the American, it begins: It's my lunch hour so / go for a walk.... I like the poem, sometime

I'll write it out complete, but just for now I've got this OK Bazaars plastic packet

in my left hand, and my right hand's in my pocket (out of sight), how else to walk lunch hour summertime Cape Town with one gloved hand? And now I'm going past The Cape Clog —Takeaways, it says it's The Home of The Original ham 'n cheese—Dutch Burgers, past the unsegregated toilets on Greenmarket Square. A cop van's at the corner. On a bench 3 black building workers eat from a can of Lucky Star pilchards. They're in various shapes & sizes.

It's a fact.

Though you'd think

post boxes'd be all just one size. I'm sweating a bit, heart pumps, mouth dry, umm Gone one, I say slipping past the Groote Kerk when an Iranian naval sailor asks What's the time? IRANIAN?

—yessir,

it's 1975, the shah's

in place, the southeaster blows,

there're gulls in the sky,

two cable cars are halfway

up or down (respectively) and

outside the Cultural Museum

an old hunchback tries

to flog me 10c worth of unshelled

nuts. He's been here

since I was 15

trying to be Baudelaire,

I'd maunder

round town watching women's legs, but now I've only

eyes for postboxes and my heart's in my packet: it's one thousand

illegal pamphlets to be mailed.

"The problem in South Africa,'' she says, "is that we're still one big white country club. 1 should know. I'm a member, perforce born into it.'' There is none of the moral evasion in her voice that I've heard from other, less honest South Africans—liberal politicians, Afrikaner farmers, assorted businessmen. She confronts her complicity, exposes her cowardice; and in life and work, she prepares for the day when there will no longer be an exclusive country club.

"The terrible thing is,'' she says, "that you become accustomed to living in this permanent state of violence being done to people all the time. In that way apartheid has been so very successful, terribly successful.''

"Can you imagine a day of political judgment—for whites?'' I ask.

" 'What did you do in the Great War, Daddy?' I think there is a kind of death-wish longing in many of us, for something to be as clear-cut as that. Just as people talk about a night of long knives—that it will all happen with fear and horror, perhaps, and with great relief, that our struggle will be over.''

Gordimer does not see herself as particularly heroic for staying. "Exile as a mode of genius no longer exists,'' she said in a recent lecture. "In place of Joyce we have the fragments of works appearing in Index on Censorship. These are the rags of suppressed literatures, translated from a babel of languages; the broken cries of real exiles, not those who have rejected their homeland but who have been forced out—of their language, their culture, their society.''

White writers in South Africa, she stresses, do not face the pressure that her friend Milan Kundera, the exiled Czech novelist, faced in his native land, where he was banned from publishing anything. "It's so wrong,'' she says sternly, "to say to Athol Fugard or Nadine Gordimer, 'You're so brave.' We're not brave at all. They tolerate us because we're white. We're disliked, and we're a thorn in the flesh, but we have a certain liberty.''

Three of Gordimer's books have been banned in South Africa; her novel The Late Bourgeois World was banned for ten years. The bans are now lifted, largely because of her international reputation, but censorship laws remain in active force. She is a fierce champion of black writers in South Africa, many of whom have suffered detention, frequent bannings, and exile.

Long an admirer of Bishop Desmond Tutu, winner of the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize, Gordimer supports the United Democratic Front, the liberation movement, much of whose leadership is in jail, charged with treason against the state. With her son, a graduate of Columbia University's film school, she recently completed a documentary on resistance in South Africa. The film was shown at the United Nations, and has been distributed worldwide. "There are things a writer can do, between writing and going to jail,'' she says. "I feel you should do what you are particularly fitted to do. I just felt, since I'm a writer and my son is a filmmaker, here was something I could do.''

Being a dissident, she admits, gives her life a schizophrenic quality. "There I am spending a Sunday afternoon at a political meeting in Lenasia, one of the townships—which I do often—and then, coming back, I'm invited to some white friends' for supper. And you feel quite disoriented: you don't know where you are the tourist. Sometimes it's possible to feel like the tourist at the white supper.''

In America recently, Gordimer noted that she is often asked how she has avoided jail in South Africa, and whether this means she has not written the book she should have written. "Can you imagine this kind of self-righteous inquisition being directed against a John Updike for not having made the trauma of America's Vietnam War the theme of his work?''

"Art,'' she declares unabashedly, "is on the side of the oppressed.'' But she refuses to turn her art into propaganda—for any side. "There are some writers who became writers because they became so indignant and were stirred to creativity. I began writing out of a sense of wonder about life, a sense of its mystery, and also out of a sense of its chaos.''

Having kept that sense of wonder, despite the entanglements of white privilege and liberation politics, is Gordimer's brilliant advantage as a writer. In the novel The Conservationist she sympathetically portrays a shameless white South African capitalist. In Burger's Daughter she explores the radical legacy of a white Communist's daughter after her father dies in a political prison. In her 1982 story "A City of the Living, a City of the Dead,'' a black woman betrays a black revolutionary. How does a white woman write of this?

She crosses to the bookshelves. "One of my very first stories concerned a man who'd lost his leg. Now, what do I know about what it feels like to lose a leg? From an early age, I simply accepted that writers are very strange creatures,'' she says, reaching into the shelves. "How did Faulkner know so much about blacks in the American South?'' She pulls out an early volume of Eudora Welty's stories, opening it with great affection. "How did Eudora know so much about that traveling salesman? You see, writers have this queer extra faculty, or we wouldn't be writers—we could only sit down and write autobiography."

When I ask if there is a chance of peace in South Africa, she listens to my earnest question, and then, like all great storytellers, she tells a story from her own day, her own people, and allows her listener to draw his conclusion. "I was talking by chance to someone yesterday—in fact, he was cutting my hair. He recently became very religious. Having been a wild man-about-town, he now spends every evening poring over the Bible; it's the most wonderful book in the world, and he's now learning it backwards. He's so full of a sense of sin, wanting to be a better person, going through self-doubt and self-examination. But he stops absolutely short of anything outside his behavior toward his own personal circle. Which I find very interesting. I said to him, 'Have you read anything in black liberation theology ?' He'd never heard of it!"

(Continued on page 109)

(Continued from page 87)

Jeremy Cronin personifies the unsleeping vigilance of the young and radicalized white in South Africa. The first time I met Cronin was in a black ghetto outside Cape Town. It was a bright Sunday afternoon. Table Mountain, four miles away, was wreathed in clouds. Yachts sailing the turquoise Atlantic were visible on the horizon. The ghetto was just off the airport highway, in an area known as the Flats. According to apartheid laws, whites were not allowed in without police permission. But there were no police present as hundreds of blacks, and maybe two dozen whites, gathered for a political rally in a gymnasium. When I arrive, banners reading RELEASE THE PRISONERS OF APARTHEID and TAKE FORWARD THEIR FIGHT are pinned to the door. Onstage, a black woman wearing a purple beret is leading the swaying crowd in a familiar song. Though the words are in Xhosa, one of the dozen languages spoken in South Africa, the tune is familiar.

This land is your land This land is my land From the Great Limpopo To Robben Island From the Indian Ocean To the Kalahari

This land was made for you and me.

After three hours of songs and speeches by black leaders just released from prison, and by mothers with sons in prison, and by union leaders who know they'll soon be going to prison, Cronin is introduced. The woman in the beret calls him "comrade" and informs us that Cronin has just spent seven years in prison for operating underground in the African National Congress, the outlawed black liberation movement. There is a reverent hush in the gym. We all lean forward as Cronin, with jug ears, cleft chin, and hair banged short as a monk's, reads his prison poems. But he doesn't just read; it's a cajoling, stalking performance. Perhaps it's his stark looks, or his need to bring his art to the ghetto, which remind me of Brecht acting in his own epic theater.

He tells of staying in Pretoria's hanging prison with death-row prisoners. "On Wednesday mornings, you'd hear the woosh, woosh, woosh as the trapdoors below the gallows were opened and three more were gone. One day I heard the voices of three black political prisoners singing militant freedom songs as they waited for the gallows. The guards called them fokken terrorists,' not realizing what I was. Those heroic voices challenged me to learn how to speak with the voices of this land." His final poem, "Death Row," pays homage to those prisoners. When he finishes, the crowd, hands clasped high, surges into an anthem.

Later, when Cronin and I talk, his voice is quiet and measured, distinctly South African, with its long a's and clipped i's. The son of an officer in the South African navy, Cronin had been writing poetry before his imprisonment under the Terrorism Act. "At first I adopted a poetic distance from white society, letting my poems speak for themselves. I had yet to find a way to link my lyrical interests to my growing need to become more politically responsible in the South African situation. The poetry became more difficult, and I became much more serious about my politics."

In 1971 Cronin left South Africa for Paris with his wife to earn a master's degree in philosophy. Instead of exiling himself, he secretly joined the African National Congress, trained for underground work, and returned to South Africa to start a clandestine propaganda cell. "I was very aware that the likelihood of ending up in jail, at best—if not dying in some torture chamber—was in the cards. But it was the path that needed to be followed if one wanted to stand shoulder to shoulder with blacks in the liberation struggle."

Back in Cape Town, Cronin worked at night in a rented garage with two other activists. "We had several typewriters and an old duplicating machine. Everything had to be done very carefully—rubber gloves, illegal names, mailing thousands of anti-apartheid letters while police were watching the mailboxes to track us down. Our function was to prepare, politically, the people, to steel them for more resistance."

Pamphlet bombs, made by attaching explosive charges to buckets, were also used. "We'd leave these at bus stations, timed to go off at rush hour, when many blacks had to catch buses to the ghettos. The buckets would explode into the air, hundreds of pamphlets scattering all over. It was a spectacular way to distribute literature—people rushing and grabbing the pamphlets quickly and distributing them on the buses before the police arrived," he explains, smiling.

In July 1976, Cronin was arrested by security police. A month earlier, the police killing of the Soweto schoolchildren had sparked nationwide riots, leaving approximately one thousand blacks dead. At Cronin's trial, he and other "white Communist agitators" were blamed for causing the riots. "I honestly think the government was surprised to see huge mass hatred for apartheid," he remembers. "They felt that the stirring amongst blacks could not be a result of black leadership, let alone black anger or unhappiness."

Six months after he was sent to prison, Cronin's twenty-six-year-old wife died. "I had been able to see my wife for a half-hour through a little glass plate once a month while in prison. Something was wrong—she was getting very thin and having severe headaches. One Saturday she didn't arrive. She had collapsed on the plane coming to visit me. At the hospital a huge tumor was found on her brain, requiring an operation."

After the operation, his wife's mother came to see him in prison. Through a plate-glass window with two guards present, Cronin learned that his wife had died. "My mother-in-law was weeping and couldn't get the words out. She just held up her finger and showed me the wedding band."

He was not allowed to attend her funeral. Kept in solitary confinement, he began writing poetry again, which, he says, "allowed me to locate my suffering in a world in which other people suffer as well."

According to prison regulations, all poetry was forbidden unless submitted to prison authorities. "Those were conditions I was not prepared to comply with," Cronin says. "I composed mostly in my head, whispering and memorizing, walking three steps up, three steps down my cell. It gives many of my poems a three-step rhythm. Once out of prison, it was really a process of getting the poems down on paper."

He talks quietly, a knuckle in the cleft of his chin. There is no self-pity in his voice. I ask why, and he explains, "For someone as political as I am, it's hard to feel self-pity. There is the magnificent heroic example from millions of ordinary South Africans who don't allow the frightening conditions of the country to beat them down."

When Cronin was in prison, he had an extensive correspondence with Gordimer. In 1981, two years before Cronin was released, Gordimer published in The New Yorker "A Correspondence Course," a story inspired by those letters. "Jeremy taught me the art of writing prison letters, and it really is an art," Gordimer recalls. Cronin says, "We weren't allowed to write about politics, or the prison, only about family matters. To fool the censors we created imaginary uncles, and told fables." The letters were checked by censors for hidden meanings, encoded messages, and invisible ink. Two of Gordimer's letters did not pass the censors, and were cut to ribbons. "Nadine's writings have never been submitted to such perusal—not even by the most analytical of literary critics," Cronin says.

Now that Cronin is out of prison, he is back in the liberation movement. He has also married again. "I regard myself as an ordinary foot soldier in the African national struggle," he says. "Sometimes," he admits, "I slip away from my comrades for a few hours to write. With the boycotts, the strikes, there is so much to do, and just finding the time to write is a form of exile.

"I'm concerned," he says, "that our literature does not simply become a kind of export business, like the old ivory trade. We must ask ourselves what it means to the people here if our theater simply becomes the latest rave on Broadway, or our literature gets frontpage reviews overseas. The most important audience is here.

"Some of my poetry belongs to a white poetic tradition. But if you're performing in a fairly noisy hall where the people have just listened to a fiery political speech, you have a problem with the white poetic tradition.''

Cronin knows that freedom is not around the comer. As sunlight plays across his face, he looks toward Table Mountain. "The regime remains vigorous in its racist policies. But there is a place for writers in that struggle. We must move beyond simply smashing idols. We are faced with the aesthetic task of assisting and strengthening an emergent national culture. The talent is there—we see it each day in the poetry and drama of the black townships. Under apartheid that culture will not flourish. The struggle for political and social freedom is also, of course, a cultural struggle."

When I last see Jeremy Cronin he is dressed in a turtleneck, keeping a vigil from the sidelines of a trade-union rally in another black township. He is not here just to read; he is here to organize. Thousands of blacks are seated in rows in front of him. In three weeks they will go on strike, igniting South Africa once again. I feel I'm watching the poet at the edge of his poem "A Naming of Matches."

Row upon row in closed ranks they wait for their baptism of fire.

This one, Single.

This one, Spark.

This one.

Prairie Fire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now