Sign In to Your Account

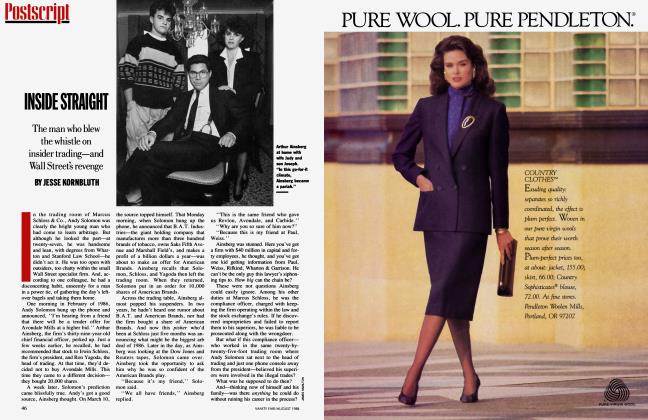

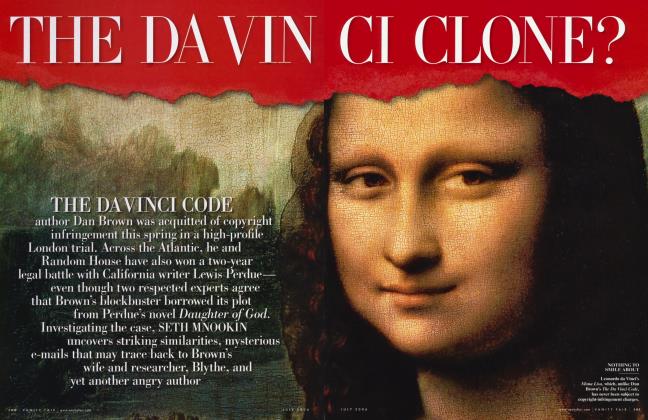

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDudley Has Moore Fun

GLENYS ROBERTS

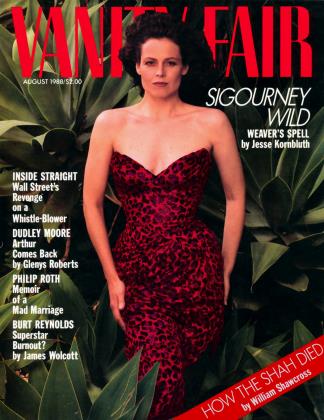

Nothing can sink the sex appeal of Hollywood's least likely heartthrob. And now, with his Arthur 2 and his shapely wife 3, Dudley Moore is set to hit the high notes again. GLENYS ROBERTS, a friend from the early days, visits him at his Marina del Rey playpen

SHORTLY BEFORE THEY WERE MARRIED THIS FEBRUARY, Dudley Moore and Brogan Lane were sitting in their den one Sunday morning watching the gas-log fire and the CBS news when the five-foot-two-inch comedian wistfully remembered the piano he used to play when he was five. It was a brownstained English Normelle upright with keys like nicotined teeth, and it had a very refined reproduction Sheraton stool with a broken handle which the child pianist had to keep banging back into place between bars so it didn't fall apart. "I wish I could see that piano again," he said.

Today it is sitting against the north wall of his Marina del Rey beach house. Brogan, who is given to endearing little acts of worship, called Dudley's sister, Barbara, in the London suburb of Upminster, and she traced it through the network of neighbors who had inherited it seven years ago after Dudley's mother died.

When his mother's piano came out of its airline crate, dud notes and all, Dudley was confronted by his whole past life. He had just finished Arthur 2: On the Rocks. This is the sequel, seven years later, to Arthur, in which Dudley's lovable drunk rolling haplessly around in his Rolls-Royce all over New York proved he could reduce audiences to helplessness by the merest tendency to slur his words. His brand of humor had crossed the Atlantic like a trade wind. The movie grossed $110 million and is still going strong. In this

era of serial Rockys and Star Treks, such box-office figures certainly called for a remake. Then writer-director Steve Gordon had a heart attack and died. So Arthur was laid to rest as well—until last year, when a young screenwriter named Andy Breckman, a Steve Gordon fanatic who knew every line of the original script, contacted Dudley with the idea of an update. The story Breckman wrote persuaded Warner Bros, to make an unprecedented two-day decision to green-light the $15 million sequel, which opens this month. In it Arthur puts an end to his drinking, solves his identity crisis, and cements his romantic relationship with Liza Minnelli.

As a piece of wish fulfillment it doesn't stray far from Dudley's real-life story. After two failed marriages and twenty-odd years in psychoanalysis, he now seems to have reached a happy plateau of self-acknowledgment and professional activity. It has been a long haul for a working-class lad from suburban England, though his mother seems to have had an inkling all along of what was to be. "You were bom on the day Byron died 111 years before," she used to tell him when he was a kid. It was an unusual link to make: the poet Byron was an aristocrat; Dudley was the son of a railway engineer. What they shared was a clubfoot, and that, for a while, was all that Dudley could see.

It is now 164 years since the day Byron died, and Brogan's "sex thimble," as she calls him, is fifty-three years old. The tall, zaftig Brogan is like a cushion between him and the outside world. She has made their California house into a great wooden playpen filled with toys and painted in primary colors. It is Munchkinland. There are CocaCola dispensers and pinball machines and rocking horses. The marital bedroom, overlooking the vast light-suffused seascape, is filled with teddy bears. When Brogan scoops Dudley up between her arm and her capacious breasts, he might himself be one of the bears.

Brogan has not obliterated past imperfections; she has glorified them. Over his favorite tuneless piano, she has hung Dudley's favorite gloomy picture, a Dutch old master of a bleak winter scene with children tobogganing. Near Dudley's other piano, a black Yamaha stretch grand, hangs a scruffy piece of handwritten sheet music she found in a trunk and has had blown up. Dudley had composed it when he was twelve. "Anxiety," he'd entitled it in a neat schoolboy hand, "Allegretto moderato sostenuto."

There are very few reasons to leave this wooden womb of a house. Sometimes Dudley goes to 72 Market, the restaurant in Venice which he owns with his director friend Tony Bill. Sometimes he goes to U.C.L.A. to see his psychologist friend Norman Cousins, who lectures on health and humor. Sometimes he is invited to make prestigious public appearances: to lunch with the Duke and Duchess of York on their recent U.S. tour; to be given his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (next to Louis Armstrong's); to play the piano at this year's Oscar ceremony.

Back home in Britain, television audiences felt a peculiar sense of loss when they saw their own little Dudley arriving chez Spago for Swifty Lazar's post-Oscar bash. This was stardom by world standards. Could this witty, self-effacing personality with the stunning Brogan towering beside him really be the same man who'd seemed content for twenty years playing the comic underdog in a cult British double act? How did he get from Dagenham, the bleak English home of Ford, where he was bom, all the way to sunny California? And why did he stay there?

Continued on page 166

Tall, zaftig Brogan, who calls Dudley her "sex thimble' is hke a cushion between him and the outside world.

Continued from page 128

Dudley Has Moore Fun

Teenage Dudley's first step was to win a scholarship to play the organ in an Oxford-college chapel. By day he studied classical music, and by night he discovered the freedom of playing jazz in student nightclubs. When he graduated he was offered a job playing the organ but turned it down. "No way could I accept that lofty post and do a nightclub act at

the same time," he remembers now.

In those days Dudley was a pianist in search of an act. He formed a musical trio, but his bass player, Hugo Boyd, was killed in a car crash. Then the director of the Edinburgh Festival introduced him to three collegiate comedians in search of some musical backing. It was a memorable meeting. The four original talents joined to create the milestone comedy show Beyond the Fringe. Alan Bennett, who went on to write brilliant plays such as An Englishman Abroad, had newly graduated from Oxford like Dudley. Jonathan Miller, now a controversial opera director, had studied medicine at Cambridge. The whip-tongued Peter Cook was a linguist at the same university, itching to bring to the London scene the sort of satirical cabaret he had seen in Ber-

lin and Paris. Edinburgh roared. London roared. Broadway roared. From 1960 to 1964 they were the wildly successful precursors of Monty Python. One American critic described it as "the moment English comedy went into the 20th century."

It is difficult now to remember the puritanical postwar Britain and its monumental sexual hypocrisy, which these four supremely literate humorists pinpointed just as the liberated society was taking off. National military service had just ended, the Beatles were still in Hamburg, Mick Jagger was practicing his gyrations in an out-of-town coffee bar. Though Dudley did not write the sketches himself, his working-class irreverence often inspired the other three. Even his height provoked one sketch, in which a ludicrous high-court judge could not see over the judicial bench to sentence the miscreant Dudley. I had never seen rolling in the aisles before, or since, but I saw it in that theater that night. All the stuffy pretensions of the English establishment were swept away in a sudden catharsis of laughter.

If any of the Fringe four seemed set for stardom in the early sixties, it was not Dudley but the tall, dark, and handsome Cook. Cook was already full of confidence and high-voltage spite. Bennett was already pondering the meaning of life. Jonathan Miller was already talking about giving up the stage and returning to medicine. "Miller has made more comebacks than Judy Garland," says Judy Scott-Fox, then Cook's personal assistant, now a William Morris agent in L.A. Dudley didn't seem to know what he wanted out of life. "He was always curled up in a comer not talking," says Scott-Fox.

That is exactly how I first remember him myself. Two graduate students had taken on the lease of an abandoned pub in Cambridge which became a literary salon for the alternative society. It was there I met Cook, who kept a room there with Wendy, an art student who became his first wife, and he introduced me to the rest of the team. As it happens, the foursome were not only neatly divided between the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, they also lined up on either side of the still-lingering chasm of the British class system. Cook and Miller, sons of privilege, would peak early. Moore and Bennett, the scholarship boys from the sticks, would take their time finding thenway in the world, but now that they have done so it is to greater acclaim. This is difficult for everyone to handle, but it's most difficult of all for Cook, who was closest to Moore professionally. Throughout the sixties and seventies Pete and Dud, as they were known, made a string of TV series, scandalous comedy records, and cameo movie appearances. Cook reacts to Dudley's absence from England like a jilted lover, and in all his stories America is the other woman.

Cook's life-style in London and Moore's in California perfectly illustrate the difference between the two places. Cook, who enjoys his smoking and drinking, lives alone with his goldfish in a historic house in Hampstead. He drops into the offices of Private Eye, the satirical magazine he helped found in the sixties and still part owns. For him, as for thousands of other British people, the freedom to be neurotic, even masochistic, greatly enriches the quality of his life. Cook sees Dudley's life in America as simplistic. He sees him lost to agents, star worshipers, and vacuous androids remade by the surgeon's knife in Venice, which is "a ghastly place full of factories, freaks, and health fascists."

Over lunch, with a cigarette in one hand and a forkful of kidneys in the other, he explained: ' 'The problem with California is not that it turns you into an orange, as they used to say. It's O.K. if you're an orange. You just hang there on the tree. You don't have to get up at 5:30 and go jogging. Brogan has Dudley white-water rafting, would you believe? Brogan has Dudley skiing at Mammoth." Peter Cook was revving up for one of his wicked comic riffs. "She has had a special boot made for his foot. She marches him up and down the side of the Grand Canyon before breakfast. So what if there is no room for a lap pool in Dudley's backyard? Brogan will find a way of installing one. It will be a vertical lap pool. Dudley will have to swim down it, not up, nothing easy. After he has done the required number of laps, Brogan will open a little hatch in the bottom of the pool and allow him in for a lightly boiled egg."

Cook, as usual, hits a nerve. Ever since I've known Dudley, people have taken this "Nanny knows best" attitude to him.

"He's always been latched onto by other people trying to make him do what they want," says Judy Scott-Fox, who remembers one typical New York evening during Beyond the Fringe. He was in a jazz club, of course, leaning against the back wall, nursing a drink and an aura of anticipation. He never appeared to have any plans, but when someone cast him in a role of their making, he always came up trumps. "A young actor, who has now become an infamous director, took him to the Village Vanguard and insisted he play. Everyone thought, Here goes this dreadful amateur. But Dudley sat down at the piano and you could just see the respect building."

Dudley played with all the jazzmen: Gerry Mulligan, Oscar Peterson, Eddy Duchin. Still, no one saw him as a star in his own right. Most people's reaction at the time was that of Sir John Gielgud (who was later to play his butler in Arthur, and who reoccurs as a hallucination in Arthur 2). They almost recognized him. Gielgud once met him in those days in the V.I.P. lounge at London airport when Dudley was off to Portofino for a holiday. "Darling," Gielgud said, "you must look up my friends Rex Harrison and Rachel Roberts, who have a home there. I will write a note introducing you." When the note was read out at the Harrison home overlooking the Gulf of Genoa, the absentminded Gielgud had written, "Darling Rexie, This is to introduce the brilliant young accordionist Stanley Moon."

Dudley never seemed to mind about this apparent facelessness. He kept saying he only wanted to be happy, and he went about it like most other people during the sexual revolution. His music hit the G spot every time. Girls hung round him when he played, and a succession of leggy young blondes were happy to share his bed. In 1963 he first met his future wife the child star Tuesday Weld. She was twenty years old, had already had a nervous breakdown, and had starred in The Five Pennies and Return to Peyton Place. Dudley, however, followed his work back home to London. "I get plonked down by life" is how he explains it. He married a knockout beauty, the English actress Suzy Kendall, with whom he starred in the film Thirty Is a Dangerous Age, Cynthia. "Mild star vehicle for a very mild star," wrote the cinema historian Leslie Halliwell.

So far, pretty predictable. Like every other successful British graduate, Dudley settled in Hampstead under the blue memorial plaques to those painters and poets they had studied in college. But there was a difference. "Even in those days Dudley and Suzy had a remarkable life-style," remembers Fiona Lewis, then an actress, now a Hollywood scriptwriter. "They had a secretary and a Ferrari before anyone else did. It was clear they intended to go places."

Come the seventies, and going places, Dudley was back in New York again, double-acting with Peter Cook in another stage show, Good Evening. This time, however, when Cook returned to London, Dudley married Tuesday and stayed in America. She found the house in Marina del Rey to make a home for the son she was expecting. Dudley gave her a budget and plonked off to work in New York. The budget at the time stretched to a twostory, three-bedroom house near the airport. "It also overlooks the public lavatory and a bird sanctuary," Dudley observes. The sanctuary is a barren acreage of wire netting and bare sand, the province of the California least tern, which behaves like something out of Hitchcock if you go near its eggs.

If the beach was Hitchcock, the house was Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The marriage to Tuesday, which split up more than twenty times, seemed doomed from the start, for I remember Tuesday too. By this time I had lived in Hollywood and returned to London to marry the English tailor Doug Hayward. All sorts of outsize person-

alities, including Tuesday Weld, would turn up at our house for fittings or fun. She left sucked cigarette butts all over Europe in an effort to give up smoking. She traipsed around like a gypsy with a small bundle under her arms, which turned out to be Natasha, her daughter by writer Claude Harz. I once found her sitting on my doorstep on the sidewalk in the middle of a crowded London street, drinking vodka. She would smile at you like an angel, but she was not easy on the nerves. "Why do you always leave the refrigerator door open?" one of her boyfriends once asked her when he came down in the morning to find everything melted on the floor. "Because I know it drives you crazy," she said.

Dudley was not up for being driven any crazier than he could drive himself. He was already in analysis trying to deal with the insecurities which he had always blamed on his clubfoot and which he had masked in humor. "I have seen Dudley almost suicidal," says Bud Yorkin, director of Arthur 2, "but he always rises." This particular resurrection was spectacular. It was 1978, and Blake Edwards, who knew Dudley from group therapy, cast him as the voyeur in search of the perfect girl in "10" when George Segal walked off the set three days before filming began. "Blake's made a new sex symbol," said Dudley's director friend Tony Bill incredulously. "Then Dudley will have to redefine sex in America," said his agent friend Lou Pitt.

At the time it looked like a bizarre piece of countercasting. The symbol was babyfaced as well as pocket-size. He made no attempt to hide the fact. There was no standing on a box a la Alan Ladd for shots with his leading ladies. The only time he had shoes with four-inch lifts made, he threw them away. He could be foulmouthed. He could be diffident. This was no traditional courtier. Yet these very imperfections made him perfect for liberated women, a vulnerable man who did not brag about his assets but turned out to be talented in all sorts of sensitive areas if you gave him half a chance. His music, for one. He could get on a concert platform with the violinist Robert Mann from the Juilliard String Quartet or the cellist Nathaniel Rosen. Or indeed with the conductor Pinchas Zukerman, the man with whom Tuesday eventually fell in love and married. "She saw his bottom when he was conducting and had to make it hers," Dudley told a mutual friend.

Where Pinchas is concerned, friends say, Dudley still gets personal. It seemed to make him mad that an imperfect mere musician could take his wife away.

Dudley had so many talents he did not even realize they were talents. It took other people to see them instead. Like Chevy Chase. "I am probably giving away my own notices," Chase had said when he called Dud in England in 1977 to offer him a small part in his first American film, Foul Play. "You knew Dudley would find his role," says Lou Pitt today. "You always know with certain people that they will; the only question is when." The pinching of Tuesday by Pinchas was the beginning of it. It drove Dudley, the winsome child showing off his scales, the brilliant organ scholar inhibited by centuries of musical references, the closet composer afraid of his own limitations, back to the Yamaha grand to find just how good he could become if he put his heart into it. He appeared at the Hollywood Bowl with a rendering of "Rhapsody in Blue" and went on to take part in a Weber trio for the Los Angeles Chamber Society. He performed Bach, Mozart, Bartok, and Delius in New York, and in 1980 he was at Carnegie Hall backed by the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra in the company of Robert Mann, who had been trying to encourage him since 1959. "He is the most amazing sight reader I have ever come across," Mann says. Meanwhile, he continued to knock out the films: Six Weeks, Lovesick, Romantic Comedy, Micki and Maude, Santa Claus: The Movie, Like Father Like Son. He had decided to use all the hurts, the foot, and the failures. He had decided to try harder. Significantly, he later confessed to fellow English comedian John Cleese that the whole reason he had moved to the beach in the first place was to try to break into Hollywood comedies.

Just as Arthur 2 was in the can, Moore's old friend Jonathan Miller came to Los Angeles with his gimmicky version of Gilbert and Sullivan's The Mikado for the UK/LA Festival. Dudley played Ko-Ko, the Lord High Executioner. "You will find Dudley not changed at all," Miller had told me before I left London, and in some ways Miller was right. There onstage, primping and posturing in his pin-striped suit with his greasy hairdo and vulgar, vulnerable bravado, was the secondhand-car salesman from Dagenham Dudley might have become. There too in the "Titwillow" song sung by tiny Dudley and the towering Marvellee Cariaga, as Katisha, was the memorable juxtaposition which explains his constant childish appeal to audiences.

"One day I suddenly saw in real life what Dudley was all about," remembers comedy writer-director Tom Mankiewicz (James Bond, Dragnet). "I was staying in one of my favorite hotels in the world, the Kahala Hilton in Hawaii, and there were two figures on the beach strolling hand in hand into the water in the sunset—Dudley and his latest girlfriend, Susan Anton. As I watched them from the rear with a mai tai in hand, they walked deeper into the water and suddenly the waves were right up to Dudley's neck while they were still lapping round Susan's crotch. As a comic image you could not get much funnier. ' '

Yet I, if not Miller, did find a slightly different Dudley. It had been hard to bridge the gap between his Los Angeles present and his British past, but he was finally succeeding in doing it. Brogan understood. She called it the period of the Three M's: "Marriage, Miller, and The Mikado." The Three M's left him longing for a delayed honeymoon doing something he has always liked—touring the French vineyards.

Susan Anton was nearly six feet. Brogan Lane is six feet in high heels, a wellmade drum majorette of a girl apparently perfectly suited to such acts of discipline as Peter Cook envisages. Yet it is clear she loves Dudley, and wants to take any pain away. She is twenty-nine, but when she curls up in the cushions wearing her floppy cotton socks, she looks like a big beautiful infant who might easily fall asleep at any minute with her thumb in her mouth.

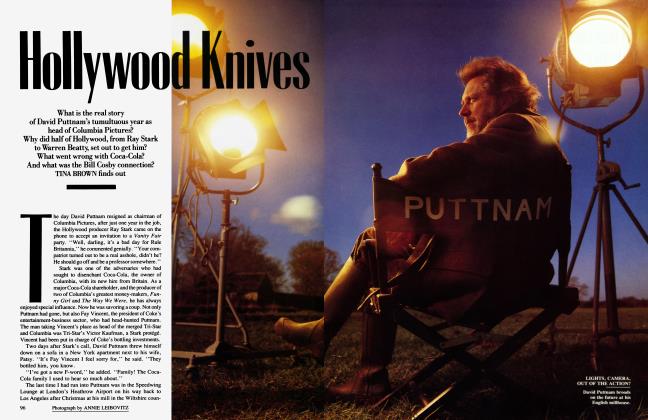

A couple of years ago, when it became apparent that the relationship with Brogan, whom he had met on a film set, was going well, Dudley had the beach house remodeled. It was dismantled to the ground, while the couple moved temporarily to the Greta Garbo house in the canyons which David Puttnam was to rent during his lightning tenure at Columbia. Gaylord Hauser had rented it from Garbo and Dudley inherited Hauser's immaculate Irish butler, Tom. Though Puttnam and Dudley both offered Tom a job, Tom preferred to go with Dudley. His job includes driving the keeshond, Chelsea, and the samoyed, Minka, to be shampooed twice a week, and making toasted hamand-cheese sandwiches for the kids. Brogan's boy, John, is fourteen, a pale, redhaired child she conceived back in Virginia when she was only a teenager herself. Dudley and Tuesday's boy, Patrick, wide-eyed and silent, is twelve.

As I entered, the house was tinkling with arpeggios. Patrick was sitting at the Yamaha, feet hardly touching the ground. For a moment I thought it was Dudley himself. Bud Yorkin told me he thinks it is hard for the eternal child to look in the mirror and acknowledge that he is no longer a child. Dudley's makeup girl on Arthur 2 was the protective Brogan. Yet

her husband, wearing a wedding band for the first time in his life, looks good for his years, with only a dash of gray in his Byronic hair. He still has the same blank innocence which allows him to be the focus of other people's dreams while digging in himself to find his own. Pamela Bell wood, the Dynasty actress, for whom Dudley played the organ when she married his best friend, dreams of him doing drama. Pitt suggests there is a wonderful side deep within him which could have played in Ordinary People or Kramer vs. Kramer. Yorkin says he is a pure comedian, and Yorkin has worked with all the lugubrious comics—Jack Benny, Danny Kaye, Dean Martin, and Jerry Lewis. "All serious people who don't sit and make you laugh. With any of them the first take is the most spontaneous, but if I had to say to Dudley, 'Try it again,' he would have us all in hysteria. Fuck it, he would say, and then fuck it in nineteen different accents from Pakistani to Japanese."

It somewhat surprised me, who has known this facility since his Fringe days, that when I went to see him this time he never did a funny voice. "Dudley gives people the Dudley they expect," warned Yorkin. Interviewed by a sex magazine, he had been shockingly explicit about sex. With me he tried to analyze what had happened to all our expectations along the way. For a moment he dropped the sweet, dissembling mask and involuntarily showed me the two clues to his success. They were complete professionalism and creative curiosity. The professionalism he had learned from his meticulous English education. New frontiers, on the other hand, were more difficult to cross back home. Two years ago Dudley took Lou Pitt and Brogan one Sunday to a service in the Oxford college where he used to play the organ. Pitt was amazed to see Dudley, alumnus and international star, standing demurely in line with the tourists. Pitt put it down to good manners, but it has to do with inhibitions as well.

"When I started to do well, I sent my mother some money," Dudley remembers. "I was earning more money in a week than she had saved during her whole working life. What did she do with my money? She did nothing. She never bought another house and she never came to see me abroad. When she died she left the money to me. When I said on television she had died in the same state-subsidized house she had lived all her life, the audience shouted out, 'Mean bastard.'

"I certainly did not expect to be living in a beach house in the sun, but there is no way that I feel out of place now that I do. I have my moments of patriotism. At Christmas I have a cassette of English carols in my car in L.A."

Tom the butler anticipated a chill in the California night and held a taper to the gas-log fire. Up above on the bookshelf, the Encyclopaedia Britannica rubbed bindings with the lives of Erroll Gamer and Schubert, and a compendium of magic. There was no trace' of Dudley's seventies reading, Montesquieu's essays, or R. D. Laing's "terribly uncomfortable world full of rich pain." Outside, through a peephole in the shutters, you could see the purple sunset and the last of the vol-

leyball games on the beach. Some California poseurs trundled their twin brindled Great Danes for an evening walk together with a brilliant blue macaw. The cozy playpen could convert quite easily again into the voyeur's paradise from "10." Now, though, there were his and hers cars in the garage with those personalized license plates with which Californians advertise their current preoccupations. Dudley's Bentley is labeled TENDERLY. Brogan's BMW reads YOGGIES for "Yo doggies," a good old southern exclamation for fun.

"I don't need drama in my life. I am not masochistic by desire," Dudley said. "One needs to work in an atmosphere of quiet, love, devotion, and patience. I don't get massively disappointed or elated

or become out of control. I think whitehot passion is something you feel when you don't deserve the object of it.

"I need less and less. I need my piano and the forty-eight preludes and fugues of Bach. I'd like to record them one day. I am not at all jaded. I don't want to be anybody else. Time was when I projected all my feelings of inadequacy on my foot, but now I would not change it for the world. I am more compassionate about my mother and more fond of my foot."

Brogan too looked at it fondly. Then, nursing the Princess Diana sapphire-anddiamond ring Dudley had given her in the Little Church of the West in Las Vegas, she did indeed fall asleep in the cushions and spread her infant peace.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now