Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

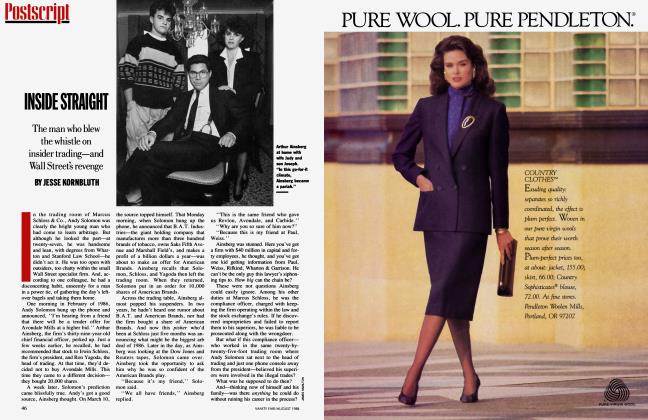

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowART BREAKING

ANTHONY HADEN-GUEST

Why did Sandro Chia fall from grace? And how was Saatchi involved?

Art

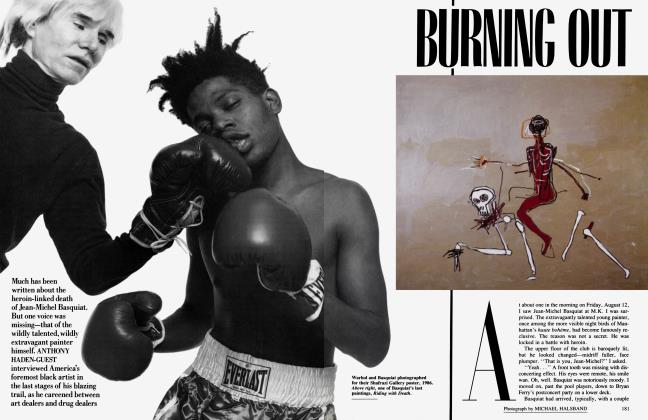

The young painter had lost his East Village gallery, he told me. The owner had left town. "He's selling shoes at a mall in the Midwest," the painter said. All over you hear talk of art people going through grim times. Consider Futura 2000, a.k.a. Leonard McGurr, a highly touted member of the graffiti group. He was photographed by magazines, appeared in documentaries, sang with the Clash, toured Germany, Japan, and Hong Kong—and the nightclub 4D had a Futura Room, "a multi-colored, fluorescent spray-painted melange of clouds, orbiting planets and rocketships," as they put it. Futura was by then showing with the Shafrazi Gallery, alongside Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf. "My

presence there seemed to give a little credibility to the whole graffiti movement, which they were pushing Keith and Kenny as," he says. "But then it seemed like the prices for the other guys were skyrocketing, and they were being asked to show in the Whitney and at the Modem, and I sort of got lost in the whole thing.

Futura left Shafrazi for the Semaphore Gallery, where he had a biting review in Artforum. Soon the Semaphore itself folded. Futura, married, with a child to support, went back to being a bicycle messenger. Then he was hit by a bus outside Macy's, and was impressed by the helpfulness of the cops—so impressed that he decided to become one. "I've taken the test," he says.

Now, the frailty of reputation, the cruelty of the winnowing are not, in themselves, anything new. Robert Indi-

ana, even Mel Ramos, used to be spoken of alongside Oldenburg, Lichtenstein, Warhol. That said, the giddying speed of the information flow does represent a change; in degree, perhaps in kind. Nothing grows stale quicker than the New, except the Neo, and in a time when artists find themselves, willingly or not, treated as fashion folks or rock 'n' rollers, surprise should be muted at finding them describing similar career paths, slow fade or flare-out included.

The most brutal example of late has been Sandro Chia.

There of Chia's is something career about that seems the trajectory to demand treatment in the meringueweight tragicomedy of one of his own canvases. He was bom in Florence in 1946 in what he describes as "the lower middle class," the son of an engineer, the salesman for an American heavyequipment company. He decided to become a painter in his mid-teens after innumerable visits to the Uffizi and the Pitti. In the sixties he was, naturally enough, caught up in the political ferment of the time, and speaks nostalgically of such radical groups as Lotta Continua, which means The Struggle Continues. "I liked very much to be in the streets in the riots," Chia says. "But I was not an activist." Chia went through a period of making "installations" and the like, but his heart seems not to have been in it. Soon he returned to figurative paintings, and the deployment of his splendid natural talents for "traditional" drawing and painting. The work was crammed with art-historical quotes, but vivid and fluent, a sort of painterly bel canto. He moved to Rome, and began showing with Gian Enzo Sperone, together with such other young converts to figuration as Enzo Cucchi and Francesco Clemente. Yes, the other two of the three C's. A critic dubbed them the transavanguardia—Italian, more or less, for "postmodernist." Then Sperone suggested a show in New York. He didn't expect to sell anything, he told Chia, the New York art market being conceptualist, and quiescent, but a New York show would look good on his resume.

Actually, the timing was excellent. It was early 1980, the year after David Salle's first one-man show at the Mary Boone Gallery, and two years after Julian Schnabel's. There was a real zing in the air, but the art world had not yet taken on its uncanny resemblance to the market in currency futures. Chia's show at Sperone Westwater on Greene Street, a dozen canvases priced between $8,000 and $15,000, opened four days after he arrived. It sold out, which, he says, "at that time was very rare."

Art

4rf/7Hfsdescribed Chia in spaghetti-Westernizing terms as "The Last Hero... like a brush-wielding Clint Eastwood."

Chia's success was an early sign of a new internationalism in the art market. He stayed on in Manhattan, which he described in rapturous terms to Interview: "There's no city in Europe comparable to it. When I look out of the window here, I don't see anything wrong. No building is vulgar." He was

with his girlfriend of many years, Paola Igliori (her mother is a della Rovere, the family of the pope who commissioned Michelangelo to redecorate the Sistine Chapel). His press coverage was superlative, rising to a zenith with an April 1983 Artnews cover story, in which he was described in spaghetti-Westemizing terms as "The Last Hero... like a brush-wielding Clint Eastwood."

Charles Saatchi, the British advertising magnate who is the single most influential collector of contemporary art, was soon buying Chia, and other collectors quickly went into a feeding frenzy. His output was prodigious—a couple of dozen canvases a year—and he was getting $60,000 to $90,000 apiece.

Chia was also living the life. He made a Mudd Club video, and won that peculiar mid-eighties accolade, a birthday party in Palladium's Mike Todd Room. Barbara Jakobson, the MOM A trustee, gave him a blow-up doll, as a comment on both his burgeoning success and the weightless figures—usually the Artist, meaning Chia himself—who float or bound across his canvases. He was also, incidentally, acquiring a reputation for enjoying the delights that art stardom makes available.

Did he believe in all this success?

"It's like wine," he told me. "You don't believe in wine. You drink wine."

The same spring as the Artnews feature, Sandro Chia had a one-man exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam—a sign of acceptance into the heavy squad (Schnabel had had his Stedelijk show in 1982). The catalogue carried an appraisal in the form of an open letter to the artist by a former director of the museum, Edy de Wilde:

Lucky the young artist who comes up at the right moment with an art that blends in with current needs. He is hailed by all the

world as a prophet, he is launched on a brilliant career. However, the artist of an older generation whose art is only too well known will have a hard time to end his career as a still successful painter. For him the impact of surprise has passed.... As a young artist who has come on the stage at the right moment, you find yourself in a favourable but at the same time unrealistic situation. You are offered exhibitions everywhere, you are surrounded by adulators who have only their own interest in mind. The situation you are in calls for character rather than talent.

In fact, the testing of Chia's character began with a telephone call in early 1984 to Sperone's Manhattan partner, Angela Westwater, from Charles Saatchi. Saatchi, who owned six Chias, wanted to beef up his Warhol holdings, and suggested a swap. He offered to exchange Melancholic Camping for a more expensive artwork, a Warhol silk-screen diptych, Blue Electric Chair. The difference would be made up in either cash or further art.

Melancholic Camping, a 1982 canvas, is an admired work. It had been in the 1982 "Zeitgeist" show in Berlin. Westwater was happy to agree. Shortly afterward, Gerry Elliott, a Chicago collector, spotted a transparency of the painting

on Westwater's desk, and instantly wanted it. This was on a Saturday. They agreed on a price in the very low six figures, and Elliott paid a deposit of $10,000. "It was a deal," Westwater says.

Meanwhile, Kynaston McShine, the curator who was organizing the whopping overall show that was to inaugurate MOMA'S handsome new expansion, decided to include Melancholic Camping. Saatchi telephoned Westwater, but couldn't reach her. Westwater is convinced that Saatchi was trying to call off the swap, and that when he found he had lost one of Chia's best paintings it soured him on the rest. Saatchi and his staff are as mute as the tomb on the subject, but the feeling that has wafted from their London museum is that the decision to "de-accession" Chia had already been taken, and that there had been no second thoughts on the subject.

Chia has another view. "Mr. Saatchi told me he only collects in depth," he said. "In depth" means collecting the work of favored artists in quantity over a period, like, for instance, twenty Salles and thirty-two Schnabels. Chia, who talks darkly of "monopoly" and "market control," says he let Saatchi know this would not be possible in his case. Whereupon, according to the painter, Saatchi decided to unload such Chias as he had.

Chia asked to buy the paintings back himself. He was told it was too late; negotiations were already under way with his dealers. At this point, Chia fired off a telegram denouncing Saatchi as a negative influence in the art world.

In a subsequent letter to Artnews, Chia wrote, "I believe the result of that telegram was Mr. Saatchi's campaign to publicize his sales of my work as a 'dispersal,' with all the resulting innuendoes, rather than the purely profitmaking operation that it was."

Julia Ernst, the curator of the Saatchi Collection, wrote her own letter, pointing out that returning the Chias to Sperone Westwater, rather than dumping them on the auction block, showed that "care was taken to avoid offending Mr. Chia or publicizing the 'dispersals.' " Ernst also wrote that, "sadly, it transpires that Mr. Chia's relationship with his dealers had deteriorated to the point where he was apparently unable to acquire his paintings from them."

Westwater says this isn't true: "I thought of replying, but why prolong the ordeal and make it worse?"

Sperone Westwater sold another of Saatchi's six Chias to a German collector, Dr. Erich Marx, for six figures; subsequently sold two others; and absorbed the remaining two into stock. Unquestionably, though, Saatchi's action threw a scare into some collectors. "Those ambulance-chasing fashion victims have got the guts of earthworms," as Robert Hughes, art critic of Time, and the Demon Barber of SoHo, put it. "They got out of Chia."

"They were offering me the work, but it was not easy to resell it," says the dealer Annina Nosei, a longtime friend of Chia's. "Also, they were offering minor pieces. So there was a moment when there were a lot of works on the market, and nobody wanted them so much."

Soon after the Saatchi affair, Chia had a sizable show at the Castelli Gallery. This was January 1985, and Leo Castelli says the show sold out, but the response, both critical and word-of-mouth, was overwhelmingly negative. "At that point, everybody was ready to talk against him," Nosei says, "the collectors, and all the people that make the art mafia of New York."

"I was aware of the change in the market," says Lucy Mitchell-Innes, who runs Sotheby's contemporary-painting department, but she adds that the rumored collapse in prices was not reflected at auction. By and large, owners seem to have decided to hang on, like savvy investors during a market panic, hoping for better days.

There is also the fact, of course, that many collectors bought Chias because they actually like them. Asher Edelman, who owns several, observes that the artist had been going through "a dry patch," but describes Chia's recent work as "very exciting." "The ups and downs are never finite," says MitchellInnes. Chia's production is way down, and his prices are somewhat softer than in 1983. (Apart from one painting in the Warhol sale, inscribed "To one of the best artists of the century," which was estimated at $20,000 to $25,000, but fetched $71,500. This may have been a symptom of the dizziness that transformed Sotheby's into Oscar night. Sperone Westwater is still asking $150,000 for the large early works.)

But what Westwater calls "the campaign of backbiting" has not much abated. One New York painter, not famous for his humility, saw a Chia on the wall facing him at a dinner party and insisted on a change in the placement. How could such a naturally accomplished artist get into such a fix? Can it be still just the aftermath of the Saatchi dispersal, or was Edy de Wilde more able a diagnostician than he could have guessed?

Chia's "dry patch" coincided with a turbulent passage in his private life. After ten years together, Chia and Paola Igliori married. They have a son, Filippo. But the marriage soon deteriorated, with Sandro Chia himself becoming the target of much art-world scuttlebutt. He discussed that, and the reverses of his career, at a couple of meetings— one in his gallery, the other in his capacious loft-cum-studio on West Twenty-third Street—not only freely, but with a sort of gloomy pleasure. "They were talking about my reputation," he told me. "When does an artist have a good reputation? It's very bourgeois. When does he care? Van Gogh, Cellini, Caravaggio—what reputation did they have?"

The marriage to Paola sundered. Chia then had a child by another woman, but is, at time of writing, according to Westwater, alone. "It's a terrible disease, marriage," he told me somberly.

This conversation took place during a small retrospective at Sperone Westwater, which another dealer described as "a defensive show—as if people need to be told how good the paintings

of Sandro are." Michael Kimmelman gave the show a thirty-two-line review in The New York Times, tacked to the end of his column. Adjectives Kim-' melman used included "depressing," "self-conscious," "strained and obvious."

Sandro Chia is not the man to take this sort of stuff lying down. "According to what I've been thinking, probably they don't want me here anymore," he said, with sardonic relish. "I am receiving the signals of refusal—almost hate. This slimy behavior—I can't stand it. Why should I stay in a place where I am not loved and appreciated?"

It should be made plain that it is the artscape that Chia is contemplating leaving, not his loft, or his country house at Rhinebeck, up the Hudson. "I like it here for other reasons," he said. "But I'm not really encouraged to have another show in New York."

Chia has, on the other hand, been energetically restoring a thirteenth-century castello at Montalcino in Tuscany, which formerly did duty as a jail for erring priests. Chia's work is thoroughly Italianate (as opposed to that of the very international' Clemente). I observed

that Enzo Cucchi had remained, painting in Ancona, that Anselm Kiefer was in his German forest, Georg Baselitz in his schloss. Might Chia have made a mistake in coming to New York in the first place?

"Yes. Probably I should have stayed —if I had been more strategic. I would have gone for this sentimental image of the artist that needs to stay close to his roots, and all this kind of bullshit, which I hated. But I was prepared to risk my arse, going somewhere else. And I don't think that any wrong has been done. No mistakes have been made. I'm pleased at the fact that the big game is, in some way, continuing. In a deeply poetical sense, I think boredom is what would kill my energies, my inspiration—and the situation in this moment is anything but boring.

"I actually think, in the back of my brain, that I tried to escape from the vulgarity of this success—this attention. Of this recording anything I was doing, thinking, or producing—the date, how much they paid for this painting—that was really scaring me. It was scaring me with the bad face of the monster of boredom! So to be out of this control is an intense subtle pleasure. It gives me a very peculiar position that I hope not to lose too soon. I mean, I wouldn't like to go back to that time."

What time?

"It was called success."

Didn't the attention have its positive side? Like getting a restaurant table.

"Now I have the privilege of having the same attention," Chia said. "But instead of being positive, now it's negative. It's a very exceptional position. They give me a table anyway—the restaurants, I mean. You never go back to zero. There is no way. Unfortunately."

What reactions has he been getting from his fellow artists?

"Unfortunately, I don't talk to other artists," Sandro Chia said. Indeed, he supplied an interesting photograph to this magazine a while back. It showed the artist on a sofa alongside Allen Ginsberg. The poet is squatting yogafashion, while an unsmiling Chia is holding a shotgun. Above them on the wall is an oval portrait of the poet Rimbaud, but this, according to the photographer, was pasted on later. What it covers is a portrait of Chia by Julian Schnabel.

The strategy is a brilliant one in its way. Chia, the artist/victim in so many of his own canvases, assumes the same role in real life with a certain morbid gusto. Clearly, though, another gust of acclaim wouldn't come amiss, and much did indeed come Chia's way with the "Palio" paintings. These four enormous canvases, executed for the restaurant of that name in the Equitable Center on Seventh Avenue, occupied the artist between May 1985 and January 1986, and they are "public" paintings, executed with great verve. So much bonhomie hasn't been seen since the canvases of Raoul Dufy.

It is possible that it is in this direction that his future lies. Indeed, he will be starting a mural for John Jay College of Criminal Justice on West Fifty-ninth Street, but he says he is no longer even returning most of the "strange telephone calls" that the Palio paintings have generated, including the one asking how much he would charge, per square foot, for a mural depicting Frank Sinatra.

The thing is that Sandro Chia hasn't really changed that much. It was the art world that changed, but then, change, devouring change, is what the art world

is all about. In the meantime, Chia is having a forty-painting retrospective at the Spoleto Festival in Italy this summer, five new canvases in the Italian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Another show will open at Vienna's Museum of Modem Art in November. "It will be a big show, with fifty or sixty pieces," says Thaddaeus Ropac, the Salzburg dealer who is organizing it. Chia is painting many of them right now in Montalcino. Ropac knows about Chia's reverses but seems indifferent. "In Europe, reputation comes more slow, but it is more strong," he says. After Vienna, the show travels to Brussels, Bogota, and maybe Caracas.

Ropac is optimistic about bringing the show to the United States. As Andy Warhol, predictive in this, as in so much else, has demonstrated, comebacks do happen. Futura 2000 sold reasonably well at his last show with his current dealer, Philippe Briet. Angela Westwater is still doing business with Saatchi: "If I disliked Charles, I wouldn't have sold him one of the best Rothenbergs from my last show," she says. Sandro Chia, anyway, strikes a characteristic note of anguished combat: "Lotta Continua."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now