Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE OTHER GUGGENHEIM

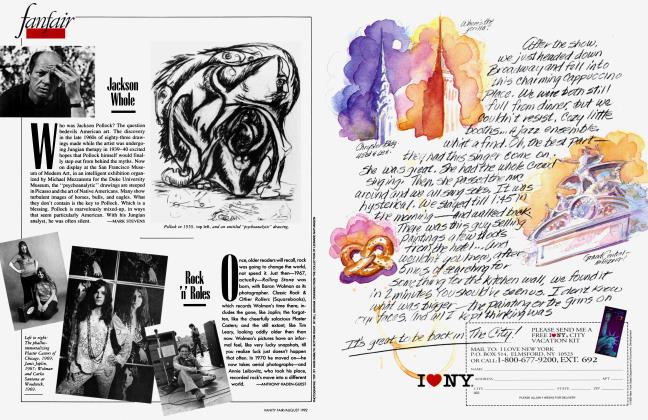

Art

Barbara Guggenheim tells the stars (e.g., Stallone) what art to buy

ANTHONY HADEN-GUEST

Three years ago, Candy Spelling and her husband, Aaron, the hugely successful producer (formerly Love Boat, still Dynasty), decided to embark upon what has become a consuming passion in Los Angeles: the acquisition of Important Art. She let it be known that she was in the market for good pieces, took the plunge, and bought her first painting—"a very small Boudin"—at Sotheby's. "Then," she says, "it started."

What started were the telephone calls. ''Some were from people that had a Van Gogh or a Van Dyck. It was hidden away in Germany or somewhere, but they can bring it out," Mrs. Spelling says. ''Really weird, crazy people. Then there was the Monet..."

One caller sent a photograph of a Monet, plus some documentation. The canvas showed Paris, and the Seine. The Spellings were told it would be theirs for $1.7 million. The Spellings said no.

A bit later there was another caller. Different name. Different price. Same Monet. ''It went through about three people," Candy Spelling says. ''Whenever I would say no to one, another would offer it to me for a couple of hundred thousand dollars less."

A friend put her in touch with David Nash, head of the Impressionist department at Sotheby's. Nash told her the Monet had actually been stored at the auction house the whole time. "Somebody hadn't picked it up, because they couldn't afford to pay for it," Mrs. Spelling says. "The price it had gone for was $900,000. Then I realized that there are a lot of weird people out there, and they are all ready to make a deal. And if I didn't have somebody to advise me who was really, truly honest, we could get really majorly ripped off."

Nash recommended an adviser. His choice—endorsed by two close friends of the Spellings, both well-known Los Angeles collectors, producer Ray Stark and Spelling's agent, Michael Ovitz— was Barbara Guggenheim.

Art consultants are nothing new. Specialists have been employed to nose out finds since collecting began. European monarchs sent out art acquirers. Bernard Berenson was a consultant, and the slippery devices that the Florencebased aesthete and his salesman partner, Joseph (later Lord) Duveen, used to milch their Gilded Age magnate clients have been part of art consultancy from the beginning. That said, the art boom of the last decade has spawned self-described art consultants in frightening numbers—one young woman recently told me that she planned to sell "Impressionistic and Post-Impressionistic art" to rich Japanese, then got in a bit of a muddle identifying the artists. There are, of course, some thoroughly qualified consultants who put together corporate collections. There is also the consulting that Barbara Guggenheim specializes in. "A fresh field," she claims. "I invented it."

What she does is assist well-heeled individuals in building their collections. Corporations—especially those with stockholders to listen to—tend to build worthy, unadventurous collections with single pieces by big names, the sort of collections that look like a liquid asset. Most art consultants claim to be leery of dealing with private collectors, who are a more willful bunch. This is Guggenheim's specialty. She says she places about two hundred artworks annually, and Stuart Pivar, an astute collector, believes that Guggenheim's annual turnover may be as much as $50 million, though Guggenheim, after some hemming and hawing, refused to confirm this.

We were talking in her office, which occupies a floor of a town house on the Upper East Side. It is carpeted in gray, and dotted with a few bits of chinoiserie left by a departed co-tenant, who used to deal in the stuff. Prints, drawings, and canvases, in or out of containers, are stacked against the walls and up and down the stairs. Guggenheim owns none of them. "That's one difference between a consultant and a dealer," she says. "I have no inventory." Meaning no vested interest in making a specific sale.

She was sitting next to the telephone and three bristling Rolodexes. Slender, with green eyes, flyaway cheekbones, and shoulder-length blond hair. She is somewhere in her late thirties, and she comports herself not exactly as if unaware of her striking good looks, rather as if they were irrelevant in the working day. Her manner is academic, even shy—except that it is often subverted by explosions of thoroughly urban humor. In short, Guggenheim doesn't have a Manhattan attitude, much less a Los Angeles one. She was bom in Philadelphia, the elder of two daughters of an art-loving mother and a father who was moderately successful in the retail trade. Unlike many in this field, she never dreamed of being an artist herself, but fine-tuned her ambitions early. "I was at a summer camp in my early teens," she says. "One of the counselors gave a lecture, and talked about a friend of his who was a curator. I raised my hand, and stood up in the middle of the room, and I started to scream. You mean, somebody gets paid to look at paintings?"

"Stallone had been collecting avidly for a long time. He likes heroic images...physical things, things with drama."

Guggenheim went through various Quaker schools in southern New Jersey, then Columbia. Her father was "no great believer in higher education for girls," so she supported herself, at first with a nocturnal job at PB 84, where Sotheby's used to stack up its secondrate material. "It was the perfect job," she says, "a wonderful hands-on education. I got to help catalogue porcelain, glass, sculpture, paintings. .

Guggenheim got her M. A. in one year flat. "I thought, That wasn't so hard, now I'll go after a Ph.D.," she says. While she went after that—in African art—she was recruited to give lectures at the Whitney Museum by Helen Ferrulli, who was launching a free lecture program there. "Barbara was the one everybody wanted," Ferrulli says. "Not only was she beautiful, but substantially well informed. She talked on the modem material, the folk-art material, even the American Indian material. You're really putting your head on the chopping block. Hilton Kramer may be out there. Or John Russell, or any number of artists. But it's a gift, and Barbara has it."

Guggenheim moved from Sotheby's to Christie's, which was then opening in New York. "I headed their primitive-art department," she says, "and they had engaged somebody to do their American department, who wasn't coming for however many months. So I took on that, too." She was still lecturing at the Whitney. At the end of one lecture, a woman asked if Guggenheim would take her and a group of friends on a—paid— tour of the Manhattan art world.

Thus Art Tours of Manhattan was bom, its two first employees being Guggenheim and her sister, Eileen, who had also now arrived in town to study art history, and whom Barbara was supporting. "I realized I didn't want to work for anybody else," Guggenheim says. "The art tours were really starting to move. So I left Christie's and concentrated on that."

"She didn't take her Ph.D. and secrete herself in academia," says Helen Ferrulli. "I was fascinated to see Barbara go out and try something a hell of a lot more risky."

Barbara Guggenheim still lives in the modestly sized but pleasant apartment in the East Twenties where she launched the tour business more than a dozen years ago. You would expect an art consultant to have quite a collection of her own, and you would be right. Two collections, actually. "My household collection is really my best," she says. It comprises novelty-store miniatures of appliances, which include a washer and ringer she was given by Andy Warhol. The other, a salt-andpepper-set collection, is larger. She owns shakers in the shapes of ice-cream cones, hot dogs, Mr. Peanuts, even china tree trunks respectively inscribed I'm Full of Pand I'm Full of S-, and a couple of Venus de Milos that dispense the condiments through the nipples. Both collections fit neatly onto the small shelves beside her refrigerator. "I'm not very acquisitive," she says, the irony wholly intended.

The art tours were a smash. "We called them culture blitzes," Guggenheim says. "We included everything— theaters, hotels, restaurants." Her payroll swelled. Then, at the end of one of the tours, a woman told Guggenheim that she and her husband had a Manhattan apartment newly decorated by Angelo Donghia. Could Guggenheim possibly advise her on some art to put in it? Thus began the art consultancy.

Envious art-world tongues have often said that Guggenheim's success, especially outside Manhattan, owes something to her famous name, and that, moreover, she is a faux Guggenheim. The tongues talk twaddle. "There is some family connection, but it's not significant," she says. "The other day I was playing tennis with a pro, and he said, You see that guy over there? He's a real Guggenheim." The guy was Roger Straus the publisher, Solomon's great-nephew, Peggy's second cousin.

Barbara Guggenheim giggles, explosively. "I said, Do you see that guy over there? He's a real tennis pro."

She adds, with another yelp, that Thomas Messer, who ran the whirligig landmark museum on Eighty-ninth Street and Fifth Avenue named for those earlier Guggenheims, had jokingly given her a free pass. "He said he was sorry for me," she explains.

Over fifty collectors now work mostly through Guggenheim. Sometimes she will be paid a retainer while working on a collection, sometimes a commission on individual purchases, and it is here that one enters the thicket of ethics. The art world is rife with deals and covert commissions—from artists, galleries, auction houses—but Guggenheim is known to be both savvy and scrupulous. It is this, more than anything, that has commended her to the gun-shy carnivores of Los Angeles.

"Some dealers think movie people are gullible morons," a Los Angeleno told me. "I remember this smooth, pinstriped Brit coming over and trying to sell Candy Spelling a painting. He made an appointment. He had to go in through the back door, and was kept waiting for a long time. Then she told him to go and deal with Barbara anyway."

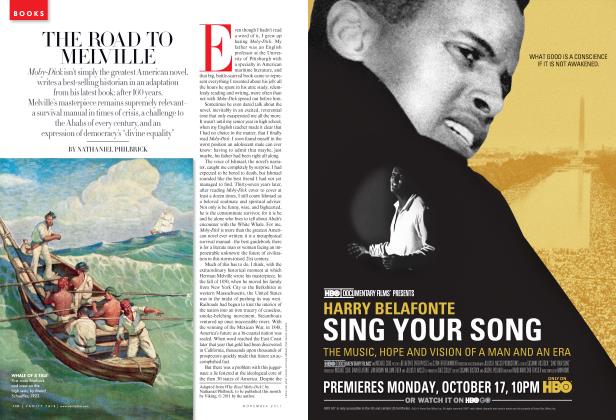

If the Spellings employed Guggenheim almost from the start, Ray Stark and Sylvester Stallone didn't. "Stallone had been collecting avidly for a long time," Guggenheim says. "Nineteenthcentury bronzes. He likes heroic images. I would have to say that is the dominant characteristic of the things he collects. We're beginning to look at Italian Baroque. He has Rodin, Bourdelle's famous archer. He likes physical things, things with drama." She won't comment on reports that the pieces are displayed alongside a LeRoy Neiman and the vivid canvases painted by the actor himself.

Collectors sometimes get nervous if their holdings are particularized, I say. They worry about burglars.

"You think somebody's going to burgle Stallone?" she inquires.

Ray Stark had also begun to acquire art long before he met Guggenheim. He had been smitten by a Barbara Hepworth that Joe Hirshhorn had shown him. "Joe said. You like it? I'll get you one." Stark got his Hepworth. A friendship with Henry Moore started when the artist came to the premiere of Funny Girl. Soon, the producer had the makings of what he resolutely refuses to call a collection. "Just say I've got a lot of work," he says. "I'm anti-semantic."

Stark's sculptures are large, but his paintings are small, a petit format collection ranging from a minuscule Rembrandt to a tiny Jasper Johns Flag. He called upon Guggenheim specifically when he wanted to start buying younger artists—"I asked her to bring me into contemporary art," he says—but now takes her advice all over. "She has refined my judgment," he says. "She slows me down. She has saved me a lot of money. Sometimes I get enthusiastic for an image, and she convinces me it's a third-rate image. She has made me number-one professional underbidder of the year. She's very conservative. I have a tendency to go on emotion."

It is, however, with the pleasure of an autocratic man who doesn't mind being pushed around by an expert once in a while that he quotes a Guggenheim telegram: HAVE PURCHASED A MUNCH FOR YOU. NOT INTERESTED YOUR OPINION. "It's a beautiful work on paper," he says, fondly. "A watercolor."

Sylvester Stallone's opinion of his consultant was finally relayed to me sonorously by his office. "Barbara is an impeccably tutored connoisseur of all levels of art, but, more importantly, impeccably honest," he said.

What art consultants create are collections, and Barbara Guggenheim feels keenly about collections. She was brought in to look at the Goetz collection, about which John Richardson wrote in last month's V.F., and which she regards as uniquely important in the history of American taste. Guggenheim grieves at its being broken up at Christie's.

Guggenheim is insistent that her job is not to impose her own taste, but to hone the taste of a particular client, and perhaps enlarge it. "I'll take them to see new work, and I'll say at first. You aren't going to get this," she says. She sees it as her job to avoid "terrible accidents" (her phrase), or to remove such unfortunate accidents that might have occurred before she came along. One East Coast client, for instance, had to be weaned from two apples of her eye, a particularly banal Sisley and a saccharine Chagall. "She saw I hated it, and said, Well, it's a late Chagall," Guggenheim says. "I said, That's not a late Chagall. That's a posthumous Chagall." Another gurgle of amusement.

Candy Spelling says that Guggenheim has just come to her rescue once again. "I had almost purchased these very expensive urns—seven-and-a-half-foot urns that are identical to the ones at Versailles. In fact, they're in the Versailles hook. But I thought. Well, they are awfully expensive. I took really detailed pictures of them, and I sent Barbara all of the information. She had them checked out. And the tops weren't done at the same time as the bottoms—they were a hundred years apart. I didn't take them. It was too much money for something that had been pieced. Now I've really got to the point where I think everyone is out to take me for everything, so it's really a great, great help to have someone like Barbara."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now