Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

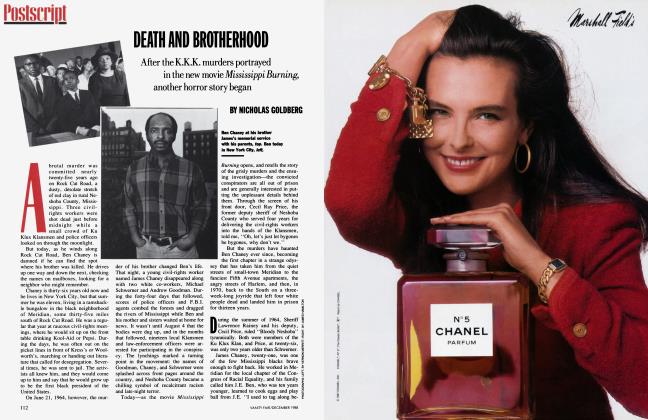

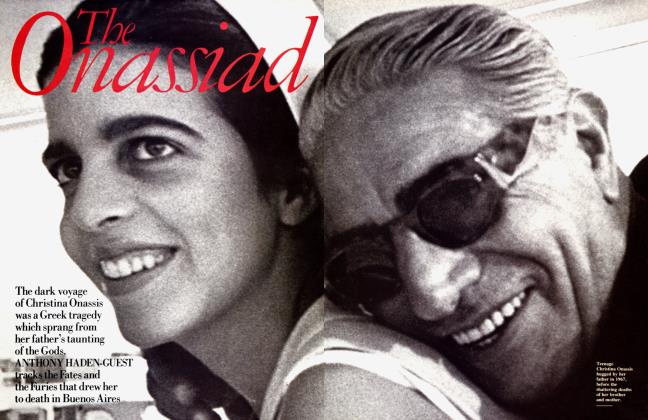

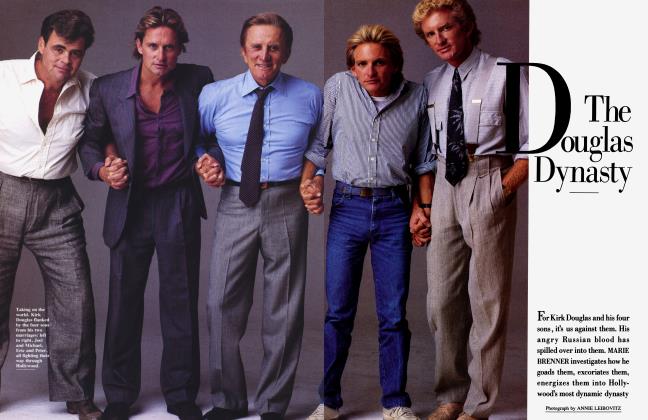

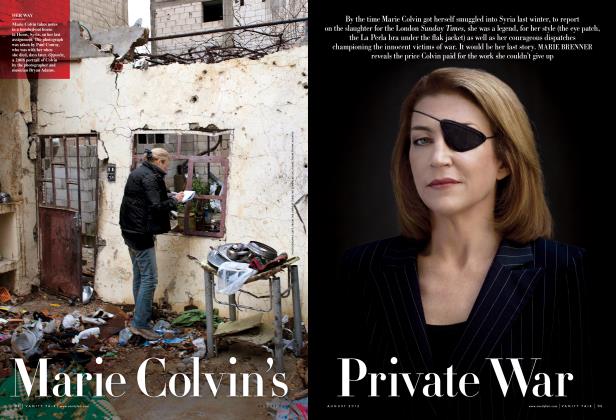

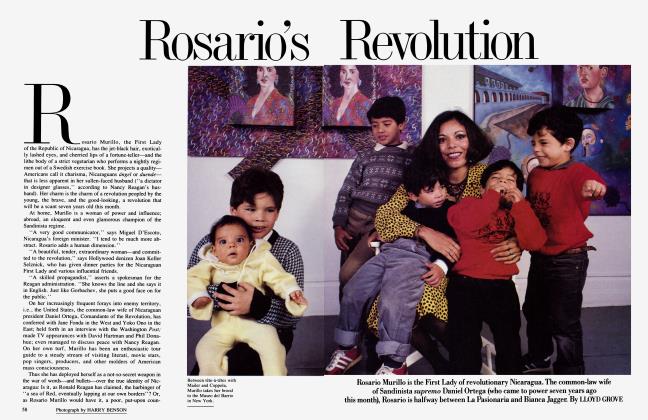

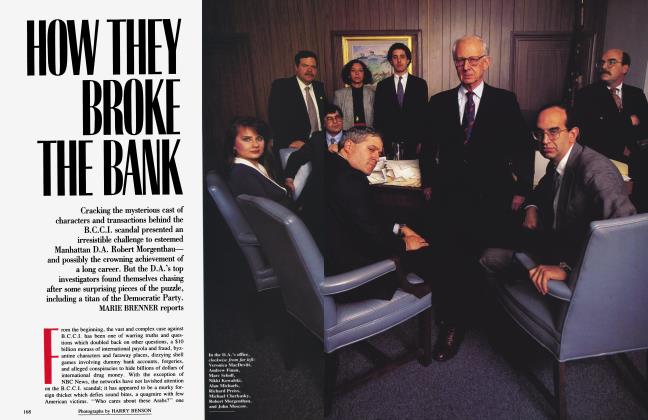

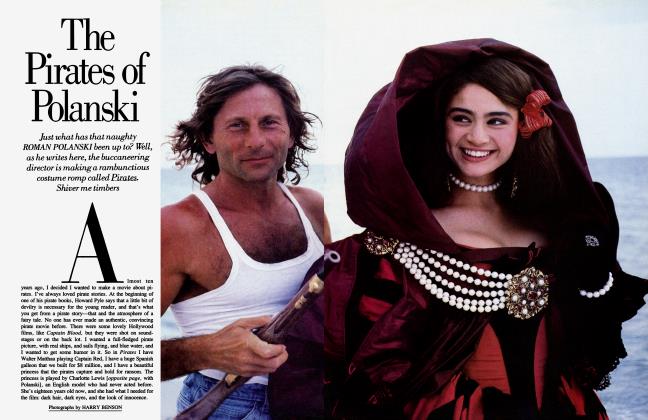

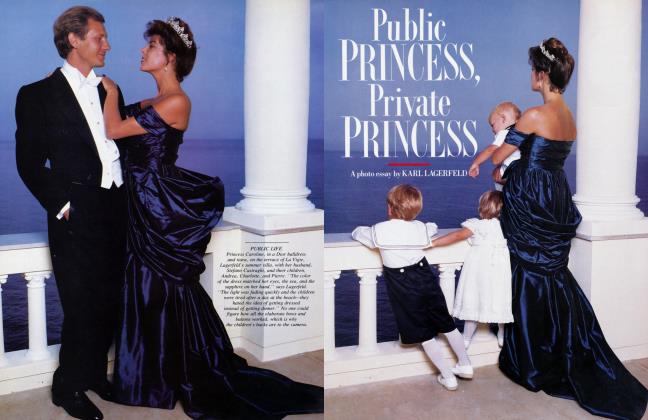

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCharacter is destiny. The seeds of Bess Myerson's fall from grace were sown early. But it took her folie à deux with Mob-linked Andy Capasso to bring them to bitter fruition. And, as MARIE BRENNER shows, the former Miss America's private degeneration meshed with the degeneration of New York City politics in an era of corruption

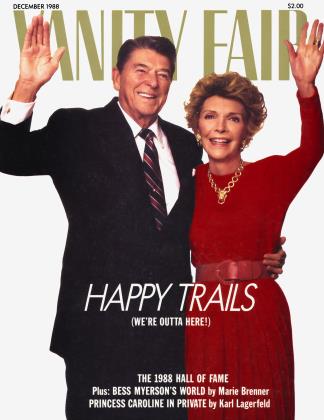

December 1988 Marie Brenner Harry BensonCharacter is destiny. The seeds of Bess Myerson's fall from grace were sown early. But it took her folie à deux with Mob-linked Andy Capasso to bring them to bitter fruition. And, as MARIE BRENNER shows, the former Miss America's private degeneration meshed with the degeneration of New York City politics in an era of corruption

December 1988 Marie Brenner Harry Benson'Obsession!"

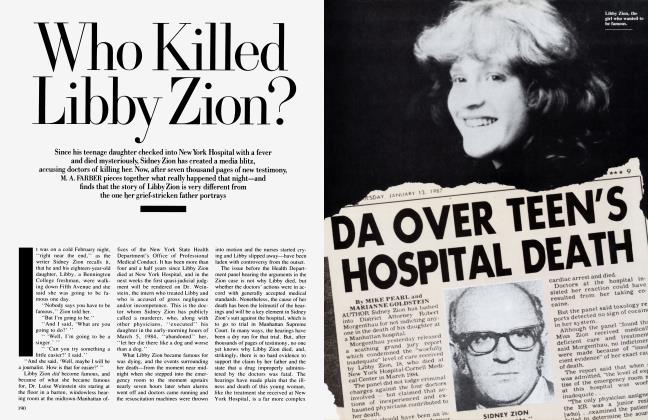

There it was, the awful word, ringing out in the courtroom on the first day of the Bess Myerson trial, as it has come to be called in the New York tabloids, although there are two other defendants in this odd and degrading case. All morning long, Bess Myerson had just been sitting there in her good ladies 'lunch striped suit, cool and composed at the defense table, taking in the head prosecutor's endless tirade covering her alleged misdeeds, sexual immoralities, manipulative phone calls, calculated dinner parties, false letters, and lies. "This is a case about money and greed and the abuse of power," prosecutor David Lawrence told the jurors. His image of Bess Myerson was not pretty, was not anything anyone would ever want to hear about oneself, but it seemed to glide over Myerson as if he were talking about an entirely different woman, or perhaps a different part of her that she had finally come to accept. The glare in the courtroom bounced off the gold rim of her glasses through the drone of this catalogue of indiscretions, but only once did Myerson seem to react at all. "Her obsession with [her lover's] divorce meshed completely with a judge's obsession for the welfare of her daughter," the prosecutor said, and a moment later Bess Myerson, perhaps finally weary of her pose, took her glasses off, rubbed her eyes, and sighed.

The Bess Myerson case has captivated New York not just because it concerns love, sex, and money, but because it illustrates a much larger story of New York in the 1980s. Famous women all over the city who have told their own lies and raised themselves from their own miserable childhoods are identifying with Bess Myerson, who has been their friend for years, and wondering what it was in her character that appeared to cause her to enter into a folie a deux, a shared madness, with a sewerage contractor twenty-one years her junior who is now serving a four-year prison term for tax evasion. She seemed to be convinced, as one friend put it, "she could take her unscrupulous crook of a boyfriend and shove him down society's throat." There are those who believe that Myerson is merely a victim, a fool for love, but her dilemma appears to be far more complicated than that of turning into a weak-willed simp who was manipulated by a man.

Bess Myerson, the former Miss America, supreme Jewish fund-raiser, television personality, and public servant, the woman who was instrumental in helping her friend Edward Koch win his first election as mayor of New York, is being tried on six counts of mail fraud, attempted bribery, and conspiracy, allegedly committed while she was a New York City official. A sad episode last summer in which Myerson was arrested for shoplifting forty-four dollars' worth of earrings, sandals, and nail polish has no direct bearing on this case.

Bess Myerson long has been a fixture on the Upper East Side social circuit, celebrated not just because she was a well-preserved ex-beauty queen. Her Bronx accent long since parked uptown, she has nurtured her public image with her musical ability, street smarts, and genuine intelligence. She has mastered the New York way of establishing intimacy through emotional displays; she is the kind of person who caresses your arm while she talks to you, a Jewish mother who will dust your lapels, tell you your legs are flabby, instruct you to take calcium pills, and belittle you if you don't do things the way she likes. Often she tells reporters she hardly knows, "I know you're sympathetic" or "You seem to be such a nice person." "I feel things," she told me recently. "I know who is with me and who is not."

For years Bess Myerson was at the best tables in noisy bistros, at the little lunches for influential "women leaders," and at the right big parties. Just about anyone in the city would take her calls. Like many of the brightest women of her era, she had to establish her name on the new medium of television. She always wore a mink on her daily appearances on The Big Payoff, and for nine years she exchanged quips with Henry Morgan and Betsy Palmer on I've Got a Secret. Television was the perfect vehicle for her, owing to her fine looks and her seriousness, but in New York she was always considered more than just a decorative wit who could make smart chat on game shows. She used her celebrity status generously for public causes, and would appear on any dais or at any settlement house if it would help someone out. "My life has always been about work," she told me. "That is how I define myself." Once, at a party, she met the humorist Fran Lebowitz. "If I were really rich, I'm not sure I would ever work again," Lebowitz told her. "I would just lie around and read and go to parties." "If you didn't work," Bess Myerson told her sternly, "no one in New York would ever invite you to a party again."

As Mayor John Lindsay's commissioner of consumer affairs, Myerson was not too grand to travel all through the Bronx and Brooklyn berating merchants for selling inferior mixed nuts and cheating customers with phony layaway plans. She once spent four hours in a furniture store until the owner admitted that the hidden charges on a layaway sofa would defraud a consumer of $100. She was later a failed candidate for senator from New York, but a survivor who had once married rich and could still pour herself into a gold-embroidered Trigère dress and appear, as she did at the 1986 reopening of Carnegie Hall, looking, in the words of her biographer, "every inch a Miss America." Besides working for Lindsay, she later was Ed Koch's cultural-affairs commissioner, a post she resigned a few months before her indictment for attempting to bribe a public official.

The bribe she is accused of took a unique form: no money changed hands. By New York City standards, the crime was small, but an alleged crime it was. "A stupid act, but not criminal," Myerson's lawyer argued. Myerson hired Sukhreet Gabel, a State Supreme Court justice's daughter, for a $19,000-a-year city job. At the time, the judge was presiding over pre-trial matters in Myerson's lover's divorce case. Bess Myerson is accused, in effect, of rigging a fix. Indeed, shortly after the judge's daughter went to work as Myerson's assistant, her mother, the judge, reduced Myerson's beau's maintenance and child-support payments by two-thirds, from $1,850 a week to $680. Myerson has pleaded not guilty to these bribery and conspiracy charges, as have her co-defendants, Carl Andrea Capasso, known as Andy, the man in question, and Hortense Gabel, the judge. If Myerson is not acquitted, she could go to jail for thirty years. The challenge for U.S. Attorney Rudolph Giuliani, whose office is prosecuting the case, will be to convince a jury that Bess Myerson is guilty of more than just operating in a way that many people in her world consider normal behavior.

Bess seemed to be convinced, as one friend put it, "she could lake her unscrupulous crook of a boyfriend and shove him down society's throat."

Bess Myerson operated in the glittering and opportunistic New York bazaar of favors and celebrity, hubris and betrayal, where the fashionable and the powerful routinely trade deals for deals. She was a star of this New York of smart dinners, tickets, and tables; Andy Capasso aspired to it. It might not have been Elie Wiesel's New York, but Bess's New York was a plummy small town that she thrived in. "I am going to introduce Andy to everyone," she once remarked. In this world, payoffs, money, power, and longtime loyalties form their own moral center. Clear-cut notions of right and wrong won't get anyone a top table. Deal trading among peers even has a name in this New York: implicit linkage. You do for me, I do for you. No vulgar words to seal the deal ever need to be spoken. The debts are always tacit. In 1977, when Ed Koch ran for mayor, Bess Myerson appeared all over town with him to try to dispel the rumor that he was homosexual. They held hands, they kissed, and hinted that after the election they might marry. At one small dinner party in Koch's apartment, Myerson was asked if she objected to being used in such a way. "No one uses Bess Myerson,'' she said angrily. The assumption was that Koch would name her deputy mayor, but he did not reward his friend until six years later, when he offered her the job of culture czar.

It is no coincidence that New York in the greedy 1980s has tolerated the Koch administration, which is so notorious for the amount of grand and petty corruption it contains that it has come to resemble the wheel of fortune. So far, more than fifty civil servants have either resigned in disgrace or been indicted. The former Bronx borough president Stanley Friedman, Bess and Andy's frequent tennis partner, sits in Rikers Island. Donald Manes, the former Queens borough president, made several attempts at suicide when he was on the verge of being indicted, and one of the last people to visit him before he finally did kill himself was his close friend and neighbor Andy Capasso, whom he had introduced to Bess Myerson. The sad fact is that many of Myerson's political and social colleagues were the moral dregs of the city.

"Think of it as a T account in accounting," a former city official told me. "You have favors like credits on one side and debits on the other. The debits are favors you owe; the credits are favors you get back. Everybody knows everybody else's credits and debits."

Prospective jurors had to fill out a long questionnaire for the Myerson trial: Do you think public officials tend to be corrupt? Do you think that a well-known person accused of a crime should be treated differently from an ordinary person charged with the same crime? But no legal queries and no future testimony could really answer the larger question of the case, which was the very how and why of what had brought Bess Myerson to this dreadful mess. "I have been through enough self-recriminations for a lifetime," she told me. "You want to check off mistakes? I have sixty-four years of them! And I can name you such big ones you wouldn't believe it. . .so what? I accept the fool in me. She does very strange things, but she also does wonderful things, and I must live with the fool. I can't berate myself or go through one of these self-hating periods. I can't do that anymore."

She appeared each day during the jury-selection process in a new combination of good wools and silks. Sometimes she wore a Leamond Dean suit but always plain jewelry, no stones, or polish on her nails. She is slim, and looked remarkable despite the edge of desperation which often clouded her face. In fact, she seemed far less tense than the sketch artists portrayed her. She would put her glasses on and take them off, and often her shoes as well. "This period of my life is not about posing," she told me. "The photographers outside all tell me, 'Smile!' But that is not what this is about."

"I feel an extraordinary sense of guilt about Sukhreet," Hortense Gabel said. "I have tried to help her so much, but I think it is possible sometimes for a mother to try to do too much for a daughter."

Seated next to her was her lover, contractor Andy Capasso, a friend and onetime neighbor of the recently convicted mobster Matty "The Horse" Ianniello. Capasso's lawyer Jay Goldberg, tall and tan, is the kind of legal showman who is used to having to turn cartwheels in front of jurors. Goldberg has made his reputation and fortune defending Mob members. Matty Ianniello was also his client.

In January 1987, Capasso pleaded guilty to tax-evasion charges against him, and in a grand-jury investigation a prosecutor suggested that he had ties to Mob figures involved in construction-industry payoffs. But Capasso is no cheap hood. He has always wanted to travel in a better world. One of his children attends a fine New York private school. Each morning Capasso arrived at court in an impeccably tailored pin-striped suit, as if he were on his way to a Wall Street partners' meeting. He looks like many of the men who eat lunch every day at Le Cirque. He has dark curly hair, a fleshy face, and darting eyes, which constantly scanned the courtroom, as if he were searching out enemies and friends, his eyeballs swiveling upward, inky points in a sea of white. He exuded a brittle nervousness, perhaps because he was manacled until the very moment he entered the court building. Although he was beautifully dressed, he is a convicted felon, serving time. "Andy has lost forty pounds in prison. Don't make him look so fat," Myerson told one sketch artist. "Hey, that's my ass! I recognize it," she told another briskly.

Before going to jail, Capasso operated a sewerage contracting company called Nanco, which did most of its business with the city. New York has given Nanco more than $200 million to fix its drains and pipes. He and his wife, Nancy, whom he had named his company after, lived in a $6 million Fifth Avenue duplex designed by the New York architect Robert Stem. The interior marble was so lavish that Architectural Digest once displayed the Capasso foyer on its cover, causing a phrase to circulate around the courtroom: "Andy's Baths of Caracalla." "Andy is a man who had to have everything," Nancy Capasso told me. "We had homes in Palm Beach and Westhampton, plus a condominium on the Westhampton beach. We had seven cars and two limousines. I had the most gorgeous clothes and jewels and an unlimited charge account at Martha. Andy loved me to dress beautifully, and I did. But nothing was ever enough for Andy."

When Andy Capasso met Bess Myerson, she was running for the United States Senate and had spent nearly $1 million of her own money on her campaign. After her defeat, according to someone very close to the case, Capasso' reportedly gave her nearly $1 million, perhaps in cash, to help pay back her campaign debts—a lover's gesture that certainly would have endeared him to her in spite of his rough edges and Mob friends.

He could be very rough. After Nancy Capasso discovered her husband was having an affair with Myerson, he beat her up with such severity that she had ' 'bruises which I thought were the approximate shape of his size 13 shoes all over her body," said her lawyer, Raoul Felder. "I was over on my back, kicking my legs like a tortoise," Nancy Capasso told me, "and my daughter was hysterical, trying to pull her father off me." During the jury-selection process, Judge John Keenan asked each prospective juror, "If you knew a man had beat up his wife, would that have any bearing on your ability to judge this case fairly?"

Myerson's friends are convinced that her worst behavior has inevitably been triggered when she was obsessed by a new man.

Each day, Myerson brought a small shopping bag of treats for Capasso—Hershey bars, M & M's, and once bagels, which she laid out on the defense table and lavishly spread with cream cheese. During one morning break, she showed him a dozen new photographs of her daughter and grandchild. Often they whispered to each other or passed notes back and forth. He still calls her Bessie, as if they had known each other from the days of her grim Bronx childhood, although Capasso was born in 1945, the year Bess Myerson became the first and only Jewish Miss America.

When Capasso wanted to speak to Myerson, he would put his hand on her back as if to draw her to him. She would respond by turning and putting her arms around him. These embraces were more protective than sensual, as if the two of them were shielding each other from a common danger. "We are very supportive of each other," Myerson told me. "I'm not sure that is love. I'm not sure what it is."

Nearby was their co-defendant, a nearly blind old woman named Hortense Gabel, who, until she was indicted last year, had been a prominent New York judge and political reformer. "She doesn't need a lawyer, she needs a fiddle," one observer told me, referring to the pathos of this frail lady appearing in court every day. In fact, Gabel has always been remarkably resilient. Stricken with near blindness as a child of four, she later served in a cabinet-level position under Averell Harriman when he was governor of New York. She was also Mayor Robert Wagner's housing commissioner, known as "The Lady Against the Slums." She was the first city official to alert reporters to the excesses perpetrated by the power broker Robert Moses, who gave New York not only its bridges and highways but also its slums and urban sprawl. She was later elected to the State Supreme Court, and there she sat for a decade. Mrs. Gabel, who is now seventy-five years old, wears the same conservative dresses as a defendant that she wore until recently under her judicial robes. Her cheeks, however, are now rouged with magenta streaks, a maquillage done for her at home most mornings before she leaves for court by her daughter, Sukhreet, who, before the trial began, regularly appeared on the local news outlining her plans to testify for the prosecution against her mother and her mother's co-defendants. "Despite the heartbreaking problems I have had with Sukhreet," Mrs. Gabel told me, "I have always had the highest respect for her intelligence."

Sukhreet Gabel is thirty-nine years old, a clever screwball with a history of clinical depression. She was once married to a Dutch diplomat, but fled her marriage because "all the wives would sit around doing nothing but practicing the gentle art of tinting lithographs." She was a beauty then, a double for Sophia Loren, and her wedding picture shows her as an elegant sylph in creamy chiffon. The reception was held in the home of New York socialite Marietta Tree. Mrs. Tree and Hortense Gabel were friends from the days when they attended constitutional conventions together as delegates. "She calls me Hor-tanse, not Horde," Mrs. Gabel told me. Sukhreet Gabel speaks three languages fluently and is finishing her dissertation for a doctorate in sociology from the University of Chicago; she sprinkles her conversation with quotations from Richard II and Thomas Merton. "I am what is known as A.B.D.—all but the degree—from Chicago, which has a much finer department in race relations than my previous experience at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins, which only prepares you for Wall Street," Sukhreet told the dazed jurors during the first week of the trial.

The Gabels have a paradoxical innocence about them, as if they did not know why they are suddenly besieged by paparazzi, although Sukhreet in particular has not been shy with the press. ''You are not going to believe this!" she told a friend on the telephone in her tangerine living room. ''Playboy has called up and asked me to pose! My mother thinks it's hilarious!" Sukhreet has been criticized in New York for these outbursts and for what seems to be brazen attention seeking, but she is in fact a lonely woman who mistakes the lavish attention of reporters desperately seeking headlines for genuine affection. ''I hope we can be friends," she tells them. Several of the reporters who feel warmly toward Sukhreet have told her in no uncertain terms to stop speaking out, counsel she says "I will take under advisement" and then cheerfully disregards.

The real tragedy inside the Myerson case is that of the Gabel family, modest people who live down corridors that smell of pot roast in small East Side apartments with dining "alcoves" and bookshelves filled with first-edition biographies of F.D.R. Small players at the modem New York game, the Gabels had the luck to have a famous acquaintance, Bess Myerson, who could remind Justice Gabel of her former power as a city tummler and in so doing change their lives forever. "Bess can be tough as nails, and I have no respect for her," Hortense Gabel told me. "But in her heart I think she means to do the right thing. She just doesn't know how."

At Sukhreet's frequent lunches with reporters, she uses phrases such as "characterological disorder," her description of what is wrong with Bess Myerson, and "affective disorder," her term for her own chemical depression, which led to her need for shock treatments, voluntary hospitalization, and medication before her mother's connection with Myerson hit the press. She says the pills she takes caused her to gain a hundred pounds in the last year and a half. "I get pretty tired of seeing myself written about as fat and disturbed," she told me. "Iam beginning to feel that I am on trial for my life. You can bet your boopy that these prosecutors would not be relying on my testimony if they thought I was crazy."

Sukhreet Gabel often appears pathetic and foolish on television, mugging for WABC's Doug Johnson, "I'll try not to smile so much." In court, however, she is usually lucid and stubborn, blossoming as the center of attention at last. For the trial, she wears a red wig styled in a modified beehive, which sometimes splits in the back, and she often dresses in bold colors: purple, hot pink, and green the shade of split-pea soup. She seems to be enjoying her moment in the spotlight, even under the incessant and surly hammering of Bess Myerson's defense lawyer, Fred Hafetz, a slight man with an unpleasant nasal voice and a head that thrusts forward like a crane when he is trying to discredit her testimony. "I've never been good with dates," Sukhreet told him, as she mixed up years and seasons on several key bits of evidence. "You cannot tell the jury whether or not the fifteen electroshock treatments to your brain impeded your recollection...," Hafetz said with a snarl. "Correct?" At times their exchanges become absolutely Jesuitical: "I was trained as a sociologist, not as a philosopher," Sukhreet told Hafetz when he pressed her on her evaluation of memory. But in the main, Sukhreet's sincerity may have helped her survive a damning cross-examination, proving at last that she is as capable as her mother.

For much of her childhood she was locked in a battle of wills with her mother, which she usually lost. "Every dinner at my house I would have to listen to my mother's day and how she had fought this one and that one. It was awful," she told me. At sixteen she dropped out of school, and later changed her name from Julie Bess to the Indian Sukhreet, which means happiness. This complex mother-daughter relationship is not dissimilar to Myerson's relationship with her strong-willed mother. "Bess and I got along so well together because we both hated our mothers," Sukhreet Gabel once told the reporter Jack Newfield, although she denies she made the remark. "Sukhreet was always a brilliant but withdrawn and lonely child. At her fourth-birthday party she sat under the table the entire time," Hortense Gabel told me. "I feel an extraordinary sense of guilt about her. I know she resented my career, and I have tried to help her so much over the years, but I think it is possible sometimes for a mother to try to do too much for a daughter. ' '

Certainly, Sukhreet's ambivalent feelings about her powerful mother might be one reason she agreed to testify for the prosecution. "I know I am in the unsympathetic position of appearing to be a rat," she told me. "But I think my mother is an innocent. Sloppy, yes. Too old to do her job properly, yes. Maybe even senile. But the conundrum of this case is that I cannot have a judge for a mother—a woman who has always represented the judicial system—and refuse to testify out of some notion of family loyalty. As far as the conspiracy is concerned, I don't own that problem. Bess and Andy do, my mother does. But I don't."

For years the public has provided a maze of splendid mirrors for Bess Myerson. To the public, she was intelligent as well as glamorous, "the queen of the Jews," as she used to describe herself, with some reason. The New York Times's reporters' library has nine folders bulging with the press clips of her civic accomplishments, moments in her life that had nothing to do with her ability to play Grieg on the piano and flute or her perfect body sheathed in a tight white bathing suit, which helped her to become Miss America and forever catapulted her from the Bronx into a world of celebrity she was unprepared for. Bess Myerson has spent the decades since she was Miss America mainly as a TV personality, but she has also toured the country lecturing on the anti-Semitism which tainted her year as Miss America, and appeared at colleges, hospitals, settlement houses, all without pay, to raise money for Israel, for Jewish welfare, for education. "We want to believe only the good things about you, not the bad, Bessie," an old woman told her recently when she and CBS's Steve Kroft went back to visit the Sholom Aleichem housing cooperative in the Bronx, where she had been reared.

Now, day after day, seeing a darker image reflected by a new, less splendid mirror, Myerson seems unduly calm, as if protective detachment provides her with a mechanism for survival. For years she has been a patient of Theodore Rubin, the prominent psychiatrist who wrote the book Lisa and David. She has been on the board of the Karen Homey Clinic, and often speaks in the language of the overanalyzed. "My life is filled with good endings," she told me, with certainty in her voice. "When this is over, it will be over. And then I'll get on with it. With freedom, for one thing. My daughter calls me from California and asks me, 'How are you?' and I say, 'Oh, well... outstanding.' " Her daughter, Barra Grant, has chosen to remain in Los Angeles, pleading that she is too busy as a TV comedy writer to come sit in federal court.

Myerson survived ovarian cancer and eighteen months of chemotherapy fourteen years ago with the same fortitude. "I have a little fear," she told a close friend then, "but I will get through this."

She is now fair game. "No one will even testify for Bess," a prominent reporter told Liz Smith. "They don't want to touch her with a ten-foot pole." Tipsters phone columnists saying, among other things, that she is dying of cancer and that this bombshell will positively come out at the end of the trial. Jean Harris, the convicted murderess, wrote to Bess from prison urging her to plea-bargain and do anything to avoid going to jail. Even taxi drivers wonder if she has a split personality or if she has no idea of right and wrong. With Myerson's detachment comes her hesitation to take any form of public responsibility for the consequences of her actions, and she and her friends routinely blame "the press" for her problems. "I suppose part of being famous is that people feel if they can diminish you they will only enlarge themselves," she once said. "You can't know what this experience is like unless you have been a victim," she told me. "Everyone is so punitive. And I wish I understood why." She has stopped reading newspapers and magazines. "When I hear my name on the news, I change the channel," she told me.

Her closest friends say they are confounded by her actions, but they believe that the darkness in her character has been obvious since her humiliating loss in the U.S. Senate primary of 1980. They are also convinced that the very worst of her erratic and at times disturbed behavior has inevitably been triggered when she has become obsessed by a new man.

Two summers ago, a story, perhaps apocryphal, made the rounds of a few of Bess's friends. Bess reportedly called up one of them, who recounted the conversation at a later lunch. "I have just seen the most unbelievable movie," Bess is supposed to have said. "It is called Fatal Attraction. The woman in it would do anything for love. . . . That woman could be me." In the movie, the star Glenn Close breaks into her lover's house, kidnaps his child, and kills the child's pet rabbit, among other obsessive acts. "I see all the men I have ever been in love with, and I watch their movements in slow motion in my head, like a Charlie Chaplin movie," Bess Myerson told me. "I remember this one promising this, and that one telling me that, and I am trying to understand if my relationship with men has really been so bad."

Certainly, she has had an unlucky history with men, perhaps because of the model of her parents' "Kafkaesque" marriage, as she has called it, although it endured sixty-five years. "Deep in my heart, I was in awe of my mother for the power she had over Dad. She drove him crazy, but he loved her, committed himself to her, and could not leave her. I believe that when I married, I looked for men who had my mother's controlling powers," she told her biographer, Susan Dworkin.

At the core of Myerson's parents' marriage was a legacy of guilt and anguish and the perception that the world was a dangerous and precarious place, a feeling their daughter seems to have inherited. The Myersons had every reason to believe the worst. Bess's father, Louis, had fled the pogroms in Russia when he was a child. During one virulent pogrom, when roving gangs routinely kidnapped Jewish boys for the czar's army, Louis's father hid him and his cousin under a kitchen floorboard. When the pogrom was over, Louis Myerson was unconscious. His cousin had suffocated.

Myerson arrived in America to work as a housepainter and married Bess's mother, Bella. They soon had a daughter, Sylvia, and a son, Joseph, who died of diphtheria at the age of three. Bella Myerson never recovered. "I was so pained by my mother's anguish that at times I thought it would be better if I had died instead," Bess Myerson's sister Sylvia told Susan Dworkin. Bella's grief was so overwhelming that she refused to take care of five-year-old Sylvia and became almost catatonic. Her teeth fell out, and her health deteriorated to such a degree that her husband threatened to send her to Bellevue. The conventional wisdom of that time suggested that another baby would cure her of her grief. Bella Myerson became pregnant again. If she hoped for another boy, she got Bess instead, a child conceived to take a dead son's place. Later, Bella Myerson had another daughter, Helen, but three girls in the house did nothing to restore her spirits, and she remained a discontented, hard-driving mother until her death.

Bess Myerson was born a beauty, so naturally elegant that it seemed she had been delivered to the wrong set of parents. Her mother's cheerless affect convinced her that she was "awkward and skinny," so skinny she had to wear shorts under her skirts to give her hips. She shared a small bedroom with her two sisters, and her mother screamed at her constantly that being able to teach piano would probably be her only salvation. "Practice! Practice! Practice!" her mother yelled, and in that cramped apartment the grand piano took up almost the entire living room, where her parents slept on the sofa so that their daughters could have the bedroom.

Bess Myerson was reared during the Depression. All around her family's apartment in the Sholom Aleichem cooperative, families were dispossessed. Myerson always feared that her family would be next. Her mother never bought her a dress until the hand-me-downs wore out. Later, when Bess went out to work and bought her own clothes, she would change the amount on the price tag to convince her mother she had gotten a dress on sale. Bella Myerson constantly chastised her sweet and passive husband, who earned only forty dollars a week. Often Bess would beg her mother to stop excoriating the father she adored.

Early on, Myerson's astonishing beauty became her mask and her escape. By the time she was an adept pianist at the High School of Music and Art at the beginning of the war, she was famous for her legs and her face, which radiated a surprising innocence. "Bess was so beautiful that she could take your breath away," her Hunter College classmate Bernadine Morris of The New York Times recalled. But a war was on and there were few men to go out with, and despite her looks Myerson, like many other women of her generation, began to feel that she would never marry.

It is impossible not to wonder how her life would have gone if her sister Sylvia, without her knowledge, had not entered her photo in the 1945 Miss New York City contest. "You know," Bess Myerson told a well-bred banker she used to date, "I should have married someone like you and moved to Scarsdale and had ten children. But my life became too public for that."

Stop frame: It is September 1945, the sailors and soldiers are stampeding off the ships, V-E Day has changed the world, and V-J Day is just weeks past. One of the first major peacetime events is a seaside beauty pageant, and this glorious summer the sponsors are looking for a new kind of American girl, even a college girl who might need a $5,000 scholarship. Bess Myerson of the Bronx is on the runway in Atlantic City, but her mother is not in the audience, because she thinks a beauty contest is frivolous and a waste of time. At five ten, Bess Myerson towers over the other girls; the contestant next to her is all of five three. Myerson is full of insecurities, and has had to wear borrowed ball gowns, but she is smiling for Movietone News, and her smile is so wide it seems to cover the world. Her gorgeous legs tremble ever so slightly as the scarlet roses are placed in her arms and the crown is set on her long curly hair. "Beauty with brains," the pageant's announcer brays, "that's Miss America of 1945!" Hundreds of Jewish fans in the audience scream and hug one another, as if Bess Myerson's victory is somehow a first small step toward mitigating the horrors of the war.

She was twenty-one years old, and was suddenly scooped up to attend bond rallies, ride on floats in parades, meet Libby Holman, Leonard Bernstein, Nanette Fabray. "Earl Wilson was writing columns about me. Everybody was quoting me. My picture appeared everywhere. I was having what psychiatrists call a 'narcissistic high.'.. .Believing what people told me, and, worse, believing that they believed what they told me," she once said.

But with the adulation came other life lessons for the first Jewish Miss America. At vaudeville appearances, she quickly learned that no one was interested in anything but her legs, and, moreover, that her parents had been right: the world for a Jewish beauty in 1945 was still a treacherous place. Bess Myerson entered a society where upper-middle-class assimilated Jews lived "fancy-fancy," as her mother might have said, and traditionally whispered the word "Jewish," as in "She's Jewish." Bess, who came from a protected and isolated Bronx world where everyone spoke Yiddish or was a socialist, did not understand the world of Marjorie Morningstar. She was humiliated when pageant sponsors would not allow her to endorse their products because she was a Jew. As she toured the country, she saw hotel signs that read, NO CATHOLICS, JEWS, OR DOGS. In Kentucky, as the guest of a country club, she twirled down the steps in her ball gown to hear the hostess say that she would have to be driven to the train station, that "we made a mistake thinking the members would allow a Jewish girl in the club." At the end of her reign as Miss America, Bess Myerson, hardened by insults and mortification, toured for the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith reiterating her message of racial tolerance. "I felt trapped in a disguise," she later said. One headline of the era read, MISS AMERICA SAYS: YOU CAN'T BE BEAUTIFUL AND HATE. "It was Such a shattering experience for me," Bess Myerson later said. "I think it toughened me. I said, 'O.K., if they don't want you to have what you have won, what you have earned, then you have to learn to fight your way through them.' "

Escape came through marriage. "We were raised to equate the unmarried state with a kind of death," she said, and so when a tall navy captain named Allan Wayne appeared at a convention she attended in May 1946, Bess Myerson was ready. He seemed to be ideal marriage material. His father was in the toy business, and the Waynes—changed from Wayneschenker—lived in a large West End Avenue apartment. The young couple moved in with them, and a year later the new Mrs. Allan Wayne had a daughter, Barra. But Allan Wayne was weak, and dependent on his family; he would wake up screaming from nightmares about the war. When his father died, he was inconsolable. He began to drink, his businesses failed, and he started beating up the woman who had thought she had found in him a safe harbor. During the worst of these rampages, Barra would hide in a closet. "His drinking made him impotent, and he blamed me," said Bess. "My success had once pleased him; now it angered him. His rages were terrifying to me and Barra." She wanted to leave him and told her mother. "How can you leave him?" her mother said. "You've just bought new living-room drapes."

Perhaps Bess Myerson believed she deserved nothing better. She stayed on, but she began making frequent TV appearances on The Big Payoff. Finally, after Wayne became so abusive that she was afraid for Barra, she sued for divorce and discovered that Wayne had lost almost all their money. Later she pressed charges against him for assault. He would agree to a divorce only if Bess would give him her television income and custody of their child. Wayne's own employer advised her, "Give him the money and cut your losses." She did, and Wayne allowed her to keep her child. "I can remember walking down Madison Avenue with Barra, who was ten years old at the time, and thinking, My God, we are free at last. And we went out to have pizza to celebrate being away from that awful man."

But Bess Myerson had yet to learn not to re-create the unhappiness of her childhood in marriage. She was a star now, sought after, and soon she met another man who appeared to be all she could want. Arnold Grant was sixteen years older than Bess, but he was handsome and big-time, a show-business lawyer who had been a partner of Hollywood's Greg Bautzer and had invented the concept of deferred compensation. Grant was a friend of moguls, a man for top tables and parties, and he soon married Bess, adopted Barra, and moved them into his grand Sutton Place triplex. Their engagement party was held at "21." "I am the luckiest man in the world," Grant said when he toasted his bride-to-be. For the New York that Bess now traveled in, Arnold Grant seemed to have the right bona Tides, but in fact he was another pointy-shoe primitive, hiding behind his own mask. Grant had invented himself, changing his name from Goldman and doing everything possible to distance himself from his father, a Bronx lawyer. Like Bess, he often showed the imperiousness of the insecure. "I can never remember hearing one person say they truly liked Arnold Grant," Arlene Francis said. He soon began to belittle his new wife's inability to give a proper dinner party, deal with servants, or use an oyster fork. "Arnold took me into another world," she told me. But it was a world that Bess Myerson was unequipped for. "He was the most difficult, argumentative, irrational person," a friend said. "But again Bess thought she had to stick this out because of her parents' teachings that you don't leave a marriage." They finally divorced, then remarried, after Grant forced her to sign a prenuptial agreement. Soon they were divorced again. Grant had discovered some of Bess's diaries in which she wrote of her affairs with other men. Grant, wrote Myerson, was "more like a thing I must manipulate," a not entirely inappropriate response to a man who consistently treated her badly. Grant later had a psychotic breakdown and was institutionalized.

At the age of forty-six, Bess Myerson became a single woman again. By then she had been the consumer-affairs commissioner and is often credited with having given the nation unit pricing. Although John Lindsay had been warned to "keep her away from City Hall," he wanted a Jewish celebrity to placate union leader Albert Shanker, who had insinuated that the mayor was insensitive to Jews. Lindsay also felt that Bess Myerson could do a terrific job. She toured the Bronx and told stories about her mother buying grapefruit; she called hamburger with additives "shamburger," and was responsible for getting $5 million repaid to defrauded consumers. She was at the peak of her public popularity. She published a book on consumer fraud and wrote a column for Redbook. Nelson Rockefeller did a political survey which showed that Bess Myerson had a 90 percent approval rating in the polls and could easily win a Senate race. Then she discovered she had cancer. "I told Rockefeller to send the poll to my mother," she said, and she emerged triumphant from her chemotherapy—"by never giving in to it," she said—scheduling meetings after treatments. The only sign of tension she showed was when friends came to visit her in the hospital and were astonished by her rage. "She would talk about people we knew in common in the most vindictive way," one remembered. "Fuck so-and-so, and fuck so-and-so!" But when she was out of the hospital, her public mask appeared back in place. When Ed Koch ran for mayor, she went with him all over the boroughs, eating hot dogs in Brooklyn, speaking Yiddish at the old-age homes, galvanized "by the power and love people had for me," as she said, and began to plan a Senate campaign for 1980.

Always the keeper of her own image, she was advised by her friends that she would be defeated if she did not study the issues, but Bess Myerson seemed to believe her public had always been so adoring of her that they would surely send her to Washington in Jacob Javits's seat. When asked what qualified her to run for the Senate, she replied, "I am better than most people I've met in government." Occasionally at lunches, Gail Sheehy reported at the time, when Myerson was asked what she would do for the state that Jacob Javits couldn't, she would say she was "magic" and then describe the pathos of her last husband confined in a straitjacket.

Two years before Bess Myerson ran for the Senate, at a dinner party in 1978, she was seated next to a very rich private investor named John Jakobson. Six years younger than Bess, Jakobson came from an elegant world; he had attended the best schools and camps and owned a seat on the New York Stock Exchange. He lived in an apartment in the Carlyle and was boyishly good-looking, with curly hair and tortoiseshell glasses. He was what Bella Myerson might have referred to as "refeened." At the time Jakobson— called Johnny by his friends—met Bess Myerson, he was involved with another woman, a high-spirited and beautiful divorcee named Joan Rea. "When Johnny met Bess, he threw me over. I was devastated," she told me. For a time during Myerson's Senate campaign, Bess and Johnny saw a great deal of each other, but soon the relationship waned and he returned to Joan Rea, whom he married in 1983.

"After Johnny broke up with Bess, my phone began to ring fifty times a day," Joan Jakobson told me. "I had an eight-year-old child in the house, and it drove me crazy. Then I began to get scared." Soon bizarre letters arrived for her, twenty-six in all, many with a condescending and imperious tone. She felt she was being followed, because moments after she would come home, her doorman would appear with another missive that had just been dropped off for her. "You may never have had a sou, but you will if you marry the handsome Jew," one letter read, according to Mrs. Jakobson.

Another read: "Slowly but surely we are coming up with the information you need to nail J.J. forever. We have contacts all over, and they are cooperating with us, because he is a no-good bastard. ... He has been picking up too many checks and hotel bills. Ask him for his records if he dares show them to you."

Others followed: "Your pimp friends are out of town now, but they will be back in a few days. Why don't you call and get the nerve to find out about Bess Myerson? Has been with her again. Phone her apartment at [number included]. Try to follow up on this so you will be able to handle J.J. and be ready. Isn't that a good idea? And eat so you don't look so anorectic. And let your hair grow in. A bleached blonde is ugly these days."

"We know all about you and your longtime screwing. What you don't know is that you were getting the biggest screwing of all."

The letters were always signed the same: "More follows." "I got so sick of seeing that 'More follows,' " Joan Jakobson told me. "I couldn't imagine when it would all end." Even more unnerving, the tone of the letters began to be anti-Semitic.

"The money, the money. Isn't that why your mother is encouraging you to get your Jew? Every WASP mother wants that for her daughter. God must be kind to WASP mothers and make sure the son doesn't marry the Jew girl. But the Jew boy is yours. Play it cool and you will have him, if you are still the home-wrecking shiksa we think you are." Even Joan Rea's mother in Virginia received letters about her daughter's love affair.

At first Joan Rea did not suspect Myerson. "I thought Bess Myerson was running for the Senate—why would she do anything this crazy?" she said. "I would watch her on the evening news talking about Israel, dressed in a gorgeous Stavropoulos gown, and the next morning some horrible letter would arrive." Then Myerson told John Jakobson that she was receiving strange letters, so Joan Rea called her and told her how concerned she was. She said Myerson demanded to see the letters Joan had gotten. Rea gave them to her without making copies. "I began to suspect something was wrong when Bess refused to give me my letters back," she said. "I told her I wanted to give them to the police." "Don't do that," Bess Myerson said, according to Joan Rea. "It could ruin my Senate campaign." After Rea got her letters back, Myerson showed her the letters that she had supposedly received, letters Rea would later discover she had written to herself.

Strange episodes kept occurring. That summer, Joan and Jakobson were in East Hampton at the beach. Suddenly they looked up, and Bess Myerson was standing over them doing jumping jacks. Sometimes Johnny Jakobson would come home to find Myerson in his apartment. Once, he was having Sunday lunch at the Carlyle and realized he had forgotten a sweater. He went upstairs and discovered Myerson on a stepladder in his closet. Another time, a close friend found her sitting in the lobby of the Carlyle. "Go home, Bess," the friend counseled.

The letters kept arriving, increasingly obscene, with references to "Jewish noses" and other parts of the male and female anatomy, as if a form of self-hating dementia had overtaken the writer. Joan Rea hired a detective. One day a Bonwit Teller shopping bag was delivered to the Carlyle with layers of tissue paper hiding what appeared to be a gift. It was excrement under the tissue paper. The detective said, "This is a police matter. ' '

According to Joan Jakobson, the Annoyance Call Bureau of the telephone company traced phone calls to two payphone booths, one across from Myerson's apartment, the other near Gracie Square. "The police knew she sent the letters— apparently everyone knew but us," Joan Jakobson said, a fact later confirmed in The New York Times, but hand-delivering obscene letters, while it was a violation, was hardly a serious crime.

Three summers ago, the Jakobsons closed their apartment for the season and left the letters on Joan's desk. When they returned, the letters had disappeared, and Joan Jakobson suspects that Bess Myerson came in and got them. The New York police still have some originals; Mrs. Jakobson has a few copies and her notes. Ed Koch said that he was well aware of the police report about the Myerson letters, but he considered his friend's behavior part of "a lovers' quarrel." Bess Myerson has always denied that she sent the letters, in spite of the police reports.

Myerson's Senate race began to peak in August 1980. Despite political consultant David Garth's assistance, nearly a million dollars of her own money she spent on TV commercials only underscored for voters that she was essentially a media celebrity. It was clear to reporters who covered her that Bess was in over her head. John Lindsay and Elizabeth Holtzman were her opponents, and Holtzman with her dour seriousness and years in Congress pulled ahead. "Bess wasn't prepared in her debates," an observer said. "She just kept calling herself a daughter of New York, whereas Holtzman relied on her congressional experience, which was immense." To a Democratic dinner in Queens one night, Donald Manes brought a sewerage tycoon named Andy Capasso to meet the famous Bess.

He was thirty-five years old, with two young children, and was married to a striking but solidly middle-class girl from Queens. Bess Myerson was then fifty-six, a lonely woman in the midst of a grueling campaign. Immediately, Capasso pitched in to help raise money. He reportedly drove to his construction sites and demanded contributions from his contractors.

Bess Myerson appeared to be the woman of Capasso's dreams, despite the twenty-one-year difference in their ages. She was a face and a name and the kind of woman who had lunch with Jimmy Carter or Abba Eban when they would turn up in New York. But Capasso was too naive about the hidden rules of the city to realize that he could not just rush Bess Myerson and be taken up in her world without some disaster occurring.

"I am the dumbest Jewish girl in New York," Nancy Capasso told me. She was, she said, too dumb in 1965, when she looked out the window of her grand Jamaica Estates house and saw twenty-year-old Andy Capasso on a bulldozer digging a sewage ditch, to stay away from him. At that time, the former Nancy Roth, a Skidmore girl, was trapped in a conventional marriage to a rich clothing manufacturer who had gone to Dartmouth. She had three toddlers under foot, and in her spare time she ran a handbag business with a friend. "My first husband was every girl's dream," she said. "I didn't even know that I was unhappy. I had my kids, my husband, and a lot of money. His family was elegant. I was just going along with the program." She was twenty-five. When she left her house one morning, the handsome guy she had noticed driving his bulldozer without a shirt on called out to her. "Why don't you invite me in for coffee?" She did.

"It was a coup de foudre," Nancy Capasso told me. Andy was passionate and desperate to take her away from her colorless existence in Jamaica Estates. "From the first moment, he was begging me to leave my husband," she said. But Andy was more than a morning thrill when her husband was away. His father owned the sewerage-contracting company, and the future Nancy Capasso, who was sexually dazzled, did not get overly concerned when she learned of the complex childhood Andy had had. "His father had carried on with a mistress for forty years," she told me. "Andy's psychology is very complicated. When he was a child, they kept losing everything. They would make it and lose it, make it and lose it. Andy's parents had a lovely house, and then they lost that too. Andy's two sisters were always running to get him anything he wanted. But what a family: the mother hardly speaks to the father, because of the mistress; the sisters hardly speak to each other." Andy understandably seemed to want to get as far away from his family as possible. "He was terrified of losing his money," Nancy Capasso said. "He used to have nightmares about it."

Both sets of parents opposed the wedding, but Andy and Nancy married anyway, using Nancy's divorce-settlement money to buy a home. Andy left his father to start Nanco. "He got these trucks and painted 'Nancy' on the front," Judy Yaeger, a friend of Nancy's, recalled. "She wasn't even embarrassed." Nancy introduced her new husband to her close friends Donald and Marilyn Manes, their neighbors in Jamaica Estates. Soon Nanco had a city contract and the Capassos were on their way to Fifth Avenue, a journey that would take twenty years.

Much later, in 1984, federal agents taped a conversation at an East Harlem social club in which Mafia members discussed Capasso's proposed role in the parceling out of New York construction jobs. "I read that Andy was in the Mafia," Nancy Capasso told me. "But there isn't a person who is using cement or in construction that doesn't have to deal with the Mafia, day in and day out. Sure, we knew them. Sure, we would have dinner with them. But what does that mean? You have to do business with these people. That doesn't mean you are one of them."

There were problems in the marriage. "Andy told me that he expected to go out with the boys a few nights a week," she said. "I thought he was doing business in bars." One night Andy's driver called her: Where was Mr. Capasso? It was three A.M. "When Andy came in the next morning, he said it had been a terrible mix-up, but I was so angry I went into his trousers and took out $ 1,000—he always had thousands in cash—and I went out and bought a ring to cheer myself up."

By then she had five children and was living in Old Westbury, Long Island, caught up with car pools and play dates. In her spare time, she helped out at Nanco. "I am the only Jewish girl who knows the name of every sewer and drain in New York," she told me. The Capassos had two condominiums in Palm Beach, which were decorator showcases, but they still lived in a social Sahara. Andy believed an apartment on Fifth Avenue and a house in Westhampton would certify their respectability and would provide him with a faster, more glittering world than a middle-class girl from Queens could provide.

"When Andy met Bess, their dreams collided," a friend told me. "Bess was a lonely tower, and she found a guy who was too unsophisticated to know not to act. He came into her life when sexually she was Rapunzel and her hair was hanging down." The city is a harsh place for single women, and in the middle of her Senate campaign Bess was feeling the strain. She had been reared with the notion that a woman was worthless without a man at her side, and she had always been obsessed with finding a Jewish man. But now, presumably still suffering over the humiliating loss of Johnny Jakobson, she did not discourage Andy Capasso. He was handsome in a rough way, and solicitous: "Bessie, what can I get you? Bessie, can I do something for you?" And Bess Myerson, who had never been treated well by men, could see in the mirror that Andy Capasso provided a reflection of herself that was still beautiful, sensual, perhaps even young. Andy might be primitive— "a dese-and-dose guy," she used to say—but then, Bess often called her own father "primitive," and at a vulnerable time in her life Andy was a man she could completely relax with. Having been hidden so long behind her public mask, she must have felt as if she were coming home. "Bess has been with a lot of horrible guys," a close friend of hers told me, "but Andy was the pits."

Capasso was the kind of rich who sits down at a table and shouts, "Everybody gets the biggest lobsters in the house." He gave Bess a Mercedes, furs, and later an office and staff at Nanco. He had spent millions of dollars on his houses, and perhaps to economize he had billed $337,555 worth of Robert Stem's renovation of his Fifth Avenue apartment to Nanco, calling it a business expense. Also, using addresses of residences near Nanco construction sites, he filed phony liability-insurance claims for damages allegedly caused by his company. When the checks came in, Nanco employees would endorse them and give the money to Capasso.

Money became the key to their relationship. Having suffered severe deprivations in her childhood, Bess Myerson always had a curious attitude about money, even after she became very rich. "Bess didn't get any feeling of security from her family," her friend Shirley Clurman said. "She always thought money would make her secure, but it never did." Although Myerson's lawyer claimed in court that she had $10 million from investments and her long career on television, she was famously cheap. Once, she sent a close friend wilted flowers from her house, which she asked a clerk in Gristede's to rewrap. She gave a boyfriend cuff links; when she broke up with him, she asked for them back and then gave them to her next beau. Another time, she showed a friend a dozen cashmere sweaters a manufacturer had just sent her. "I'll see if I can get them to send you one," she said. "Oh, just give her one," Andy snapped. "How am I going to come out whole after this trial?" Myerson asked me. "Do you know what I am paying the lawyers? I wonder if I could sue to recover my attorneys' fees."

"Bess was the consummate chiseler," a friend of hers told me. "She got everything for free. The designer Jerry Silverman used to give her his entire line. She was always making deals, and never thought a thing about it. It was not very classy." When a publisher sent her a complimentary copy of a book, Bess called up and attempted to order dozens. When Nelson Rockefeller suggested to Myerson a seat on a charitable board, she reportedly told him, "If I do it, I'd like an office and a secretary in your building." To a friend she said, "If Andy and I ever break up, I am never giving this Mercedes up."

Two months after Bess's defeat by Elizabeth Holtzman, her friends began to worry about her state of mind. She went underground, appeared nowhere in her glittering New York, and when she ran into old friends she would complain bitterly about the unfairness of her loss in the Senate race. Her father died about the same time. One day a story went out on the A.P. wire: Bess Myerson was in the intensive-care unit at Lenox Hill Hospital. Myerson lied even to those close to her, and put out a story that she had fallen off a ladder. In fact, she had had a stroke. When she was released, it was Andy Capasso who was there to pick up the pieces, to bring her home and comfort her with his charge cards, his limos, furs, houses, and, most important, the money that allegedly reimbursed her for her campaign debts, which her lawyers deny he gave her.

"You are going to be really surprised when you meet my mother's boyfriend," Barra Grant told a friend. "But she's happy, and with my mother that's all that matters." Bess became kittenish with Capasso, who would often yell at her good-naturedly, "Why do you talk so damn much?" He was, her friends say, the first man who could treat her like the woman she might have been had she not won the Miss New York City contest. He was not weak or psychotic, as her two husbands had been. Like Bess, he had transcended a grim childhood. Their bond was elemental, sexual, and they often talked about their sex life at dinner parties to anyone who would listen. Once, Liz Smith remembered, "Andy went on and on about how older women turned him on." Andy was so sexually possessive of Bess that she warned a single man who was flirting with her, "Please walk away from me. Andy will be very angry if he sees us together like this."

Capasso and Myerson carried on openly together, as if they took a perverse pleasure in flaunting their affair in front of Nancy. "The first time I met Bess at a party, Andy told me she said to him, T had no idea your wife was so pretty,' " Nancy Capasso said. "It was almost as if after that she was going to do anything to get him away from me."

Myerson even spent a weekend in Westhampton with the Capassos, driving out in the Mercedes Andy had given her. Whenever Nancy would accuse Andy of being in love with her, he would angrily deny it. He would tell her she was paranoid and say, "We are just friends." When Barra Grant married Brian Reilly, Nancy and Andy Capasso attended the wedding. Bess, according to a reporter, went from one person to another saying, "Be nice to Nancy."

One day when Nancy Capasso was having dinner with a friend at the Fortune Garden on Third Avenue, she saw Andy come in. She got up, put on her fur coat, and found Andy and Bess at a secluded booth in the corner. "We're having a business meeting," Capasso said as Bess looked coolly on. "I sobbed for weeks when I finally figured it out," Nancy Capasso told me. "I used to wear sunglasses to work and tell people I had an eye infection." A short time later, Nancy's friend Judy Yaeger went to the Capassos' for dinner. In the kitchen, she said to Andy, "What is going on with you and Nancy?" Yaeger said he said, "I am tired of her always thinking something is going on with me and Bess." That night, as Capasso was leaving the house, which he usually did after dinner, his daughter, according to Nancy, said to him, "Dad, are you going out with your girlfriend again?" "Suddenly, I heard terrible screams from the bedroom," Judy Yaeger told me, "and I found Andy on top of Nancy, savagely beating her. I was terrified."

Soon after, Nancy Capasso went to family court and eventually had her husband barred from the house. "How dare you take me to nigger court?" she told me her husband shouted at her. It was winter 1983. Andy Capasso filed for divorce. Fifteen million dollars was involved, and Andy first offered to settle with Nancy by giving her $500,000. She refused. In February, Bess Myerson was appointed commissioner of cultural affairs, and that spring, she started spending every weekend at the Capasso house in Westhampton. Nancy Capasso's clothes were put in garbage bags in the garage. "Bess would wear my things, even my bathing suits! Can you imagine?" Nancy Capasso said. "And Andy would not give me my own clothes back. She would use my bicycle and tell my daughter, 'Don't tell your mother.' " Andy even demanded from Nancy the scores of bracelets and necklaces he had given her over the years. "He said he wanted to have them 'appraised,' " Nancy told me. "That was the last I ever saw of my best jewelry until I saw some of it in photographs, being worn by another woman."

But at Bess Myerson's swearing-in at Gracie Mansion, according to a friend, she "stood tall, and was so elegant and composed when she spoke of what she was going to do in the city. If you could have just frozen that moment forever, Bess was the epitome of class."

It was then, the prosecution believes, that Bess Myerson and Andy Capasso became infected with a shared obsession over his divorce. One of the big questions in this case is why Andy Capasso, with his millions, would not just settle with Nancy and get on with his life with Bess. "Why would anyone bother for such small change?" a friend of Myerson's wondered. "We are talking $30,000 after taxes." But obsessions are never rational, and one can only speculate about the cause. Certainly, in Andy Capasso's case, it might have to do with the loss of what Italians call la bella figura, his loss of pride. Revenge, as the saying goes, is a dish best served cold, and perhaps Capasso felt that any way he could make his ex-wife's life uncomfortable was well worth his while. "Andy even took my daughters' cars away from them, cars he had given them," Nancy Capasso told me. Nancy planned a small Bar Mitzvah lunch for their son; Andy and Bess scheduled a lavish party in his honor at exactly the same time. Nancy Capasso was not shy about fighting back; she began scheduling interviews with the press. "Someday I am going to write a book about this," she told me.

Hortense Gabel was then working in matrimonial court, presiding over motions and pre-trial hearings. "My phone rang one day and it was Bess Myerson," she told me. "I had known her for years, but only slightly. She was crying on the telephone, telling me how brilliant some ruling of mine had been, and that it was a step forward for women's rights." Capasso v. Capasso was then pending before Justice Gabel, and on June 23 Gabel signed an order giving Nancy Capasso $1,500 a week, plus support of the children. "We thought it was fair," said Raoul Felder, who was no stranger to the notion of implicit linkage. He would later help Sukhreet Gabel find an apartment. But in May 1983, Myerson invited Justice Gabel to a reception in her honor at Gracie Mansion, and the frail, elderly judge was "thrilled to go back," she told me, because she had not been in Gracie Mansion since the days when she was there constantly, as an indispensable aide to Robert Wagner. Miss Myerson sent a city car to pick Justice Gabel up.

"Bess began calling me all the time," Hortense Gabel told me. "It was odd. Often she would leave an assumed name." Her choices were sometimes witty; "Mrs. Robinson" was one.

In June, Hortense Gabel had a dinner party in her apartment and invited Bess, who brought Herb Rickman, the mayor's assistant. Rickman was such a close friend of Bess and Andy's that he kept clothes in Westhampton; often he would entertain Myerson by singing Yiddish songs. Even Ed Koch had been to Bess and Andy's for a weekend lunch. Hortense Gabel had called her daughter several times to insist that she be present at the dinner party. "Bess Myerson is coming," she said, "and I want you to meet her." "My, my," Sukhreet said she told her mother, "we are certainly getting up in the world." Sukhreet had been in New York all that year, looking for a job and seeing psychiatrists to help her overcome her depressions. Hortense Gabel was beside herself over her daughter, even used her secretary to type and send out Sukhreet's resumes. "My friends pulled away from me," Sukhreet said. "No one likes a loser in New York." At the dinner, as everyone sat around the Gabels' tiny living room balancing their plates on their knees, Bess Myerson spent all evening talking to Sukhreet. "You know what I thought about her at first?" Sukhreet said to me. "I thought, God, Miss America is lonely." Several weeks later, Bess Myerson invited Sukhreet Gabel to dinner and talked to her about what she should do with her life. She suggested law school, and then, as an afterthought, perhaps, a job at the Department of Cultural Affairs, a job for which Gabel was academically overqualified.

In early July, Capasso's divorce lawyer approached Justice Gabel and asked her to reduce the maintenance payments to Nancy Capasso. And Justice Gabel, without providing notice or an opportunity for a hearing to the attorneys for Nancy Capasso, reduced her support payments by one-half.

Visitors to the Westhampton house remember seeing divorce papers strewn all over the living room. Bess frequently complained to her friends about "that vicious woman, Nancy Capasso." In one of Capasso's motions for review, he demanded custody of his children, saying that his wife had made them "morbidly dependent," a phrase right out of Karen Homey's teachings and one Bess Myerson often used. "I know she wrote that motion to try to take my children away from me," Nancy Capasso told me. Perhaps that was the moment, far more than when she heard Bess was wearing her clothes, that sent Nancy Capasso into her final role as the woman scorned, determined to pay back her husband and his lover.

During this time, Sukhreet Gabel was invited for two weekends in Westhampton. "Andy ruled Westhampton like a lord," she told me. "He would say, 'I'd like some toast,' and Bess in her Jewish-mother incarnation would say, 'Let me fix it for you,' and Andy would snap, 'We have servants for that!' " One day Sukhreet Gabel introduced herself to the English housekeeper. "Gabel? Gabel? Isn't that the name of the judge in Mr. Capasso's divorce case?" That night Sukhreet called her father and said, "What is going on?" "Stay out of it and keep your nose to the grindstone," Sukhreet said he told her.

Myerson later described her predicament to Steve Kroft: "I feel as though it started as a little snowball on that mountain, and then it just kept rolling and gaining speed and gaining dimension and becoming gargantuan."

In August, Sukhreet Gabel was hired as Myerson's special assistant. In September, against the original recommendation of her law secretary, Justice Gabel made permanent her order to lower Capasso's divorce payments to his wife, now taking even more money away and leaving Nancy Capasso about one-third of her original ruling. Sukhreet Gabel began to feel extremely uncomfortable about being in the Department of Cultural Affairs. "Are you aware that my mother is the judge on Andy Capasso's divorce case?" she said she asked Judith Gray, the ex-wife of WMCA's Barry Gray, who was Miss Myerson's press officer. "Don't you know that nobody is supposed to know that you are here?" Sukhreet Gabel remembered Mrs. Gray telling her. "You could do a lot of harm to Bess."

But Justice Gabel's ruling was not the final ruling in the Capasso divorce. In subsequent motions, however, which are heard routinely by a different judge, Andy Capasso's lawyers succeeded in getting the case back into Justice Gabel's court. "That was when I first began to suspect a fix was in," a lawyer close to the case told me. "Capasso's lawyers were always smiling and saying, 'Fine, fine, it will go fine,' whenever I would ask about the case." By this time Nancy Capasso had left Raoul Felder and hired a different lawyer to represent her. One of her attorneys, angry at the reduced alimony payments, allegedly tipped the New York Post's Richard Johnson off to the connections between Justice Gabel, Bess Myerson, and Sukhreet. SMALL WORLD was the Post's headline, and the story below detailed the trio's associations through the Department of Cultural Affairs. "Bess called me in and made me lie to Richard Johnson," Sukhreet Gabel told me. "I had to tell him my hiring was an accident."

That day in court, Justice Gabel reportedly asked all the lawyers present if they wanted her to recuse herself—the legal term for resigning—from the case. This was, the prosecutors are sure to point out, a subtle but important difference from a judge stepping down voluntarily because of the merest appearance of improprieties. "My mother has always been so ethical, I think she thought that her judgment would go unquestioned on this case as well," Sukhreet Gabel told me. Incredibly, the lawyers on both sides said they saw no conflict of interest. Bess Myerson then sent a letter to Ed Koch saying there was "nothing improper in the hiring" of Sukhreet. Soon after, Sukhreet Gabel was moved away from Myerson's office into a cubicle by the lavatory. "I went into the bathroom to have a good cry. I locked the door. Soon I heard somebody pounding on it. 'Who's in there?' It was Bess. When she walked by me to use the loo, she saw that I was sobbing. You know what she said to me? 'Kid, you just have to learn to roll with the punches.' "

Bess Myerson and Andy Capasso began telling friends that Nancy Capasso was wrecking their lives by tipping off the press. In January 1987, Capasso was indicted for tax evasion stemming from his phony liability claims. Capasso has told friends that Nancy went to the U.S. attorney "to ruin me." "Why would I have done that to my children?" Nancy Capasso said. A grand jury soon began investigating a $53.6 million sewerage contract that Capasso had obtained while Bess Myerson was cultural-affairs commissioner. Called before the grand jury, Myerson took the Fifth Amendment, and Koch, incensed at the appearance of what seemed to be another corrupt official in his administration, asked retired federal judge Harold Tyler to issue a confidential special report. In classic New York style, Tyler had been U.S. Attorney Rudolph Giuliani's mentor, and his report excoriated Myerson. After Koch read it, he asked Bess Myerson to resign. Capasso and Myerson then began blaming Giuliani for persecuting them because he was a headline hound. "Now I know how Edgar Hoover used to ruin lives," Myerson told me.

In April, Ed Koch invited his old friend to a Passover Seder at Gracie Mansion. Soon after that, Bess Myerson called her former assistant Sukhreet Gabel, whom she had not seen in a year. "I've got to talk to you," she said. "I am coming to your apartment." And so she did, wearing sunglasses, her hair wrapped in a scarf. "Come out and take a walk with me," she said when she learned Sukhreet's roommate was home. Then, in that odd combination of Jewish mother and raging harridan that has always seemed to define a part of her personality, she told Sukhreet first, "Put a sweater on, it's cold out," and moments later yelled at her, "You better keep your fat mouth shut! You could do me a lot of harm."

Andy Capasso was sentenced to four years in Allenwood for tax evasion. "What kind of fair is that?" Bess Myerson asked me. "Andy's judge had never given anyone more than a year and a half for the same charges." At parties before he left, he would joke, "Come visit me." Myerson did, and once was picked up for shoplifting in a local dime store. OH NO, BESS!, a New York tabloid headlined. Soon the papers had another story: Bess Myerson had been picked up eighteen years earlier in Harrods. "My mother's always stealing things," Barra Grant reportedly told friends, who speculated that Bess's need to steal was orgiastic, but perhaps it was also a plea for help.

The New York Post reported that the Genovese family had turned down Capasso's request to build a cement plant in Brooklyn because "his torrid romance with the former beauty queen attracted too much attention." At a lunch at Le Cirque with three close friends, Bess Myerson said, "I am finished with Andy. He is no good for me." Then she said, "Everything that has been in the press about me is totally untrue." Capasso even began seeing another woman, a handbag manufacturer's ex-wife named Betty Bienen, who was once photographed wearing a diamond bracelet of Nancy Capasso's. For a while Myerson and Bienen visited him in jail on alternate weekends. Some months later, a federal official leaked the Tyler Commission report to Jack Newfield of The Village Voice. "He said he did it because he was so angry Koch had invited her to Passover, as if he was going to whitewash the whole thing," Newfield told me. Soon after, Giuliani's office indicted Myerson, Capasso, and Gabel. It will reportedly spend millions in federal money prosecuting the Myerson case.

Lunchtime, federal court: Often when the jurors have been excused and Bess Myerson can drop her pose, she and Andy have lunch together at the defense table, laughing, touching arms. She leans toward Andy, serves him coffee, and urges him to finish his tuna fish. Few people are in court to see this scene, but it is easy then to imagine the woman Bess Myerson might have been in another, more normal incarnation. She would perhaps have led a life not much different from Nancy Capasso's old life, that of a beautiful Jewish woman married to yet another rich and unscrupulous New York man. "There is nothing in my life I would have done differently,'' she told me. "I have had days when I have been stuck together with paper clips and Scotch tape. And I have gone out and done what I had to do and nobody has known my state of mind.'' No doubt she is wondering what the jurors must be thinking when they see the defense's charts of maintenance costs which include $105,000 per year just to keep up the swimming pools, the marble walls, the condos, the Mercedes, and the chauffeurs, or when they hear Sukhreet Gabel chirping away for hours on the fine points of ethnographic doctoral programs and Bess Myerson's cruelties and manipulations, then perhaps devastating her own testimony by describing her memory, after months of electric-shock treatments, as being "as filled with holes as Swiss cheese.'' The U.S. attorney is determined to blanket the jury in a welter of circumstantial evidence, hoping it will add up to a federal crime. Neither side is disputing the facts of the case; what they are disputing is the interpretation of the facts, what the lawyers call "the spin." "The spin," of course, is everything—all the mazes and masks, what Sukhreet saw, what Bess knew, what Andy created, what Hortense executed. The scene at court is a carnival of obsessions: Bess's for Andy, Andy's for Nancy, Nancy's for Bess, Sukhreet's for her own stardom, with Hortense Gabel applauding her daughter's efforts, which are directed against her. There are so many agendas in this courtroom that at times, however serious the charges, even the avuncular judge appears amused. It seems to be Bess Myerson's lawyers' contention that implicit linkage is the way of the world, perhaps unethical, even tacky, but certainly not a federal crime. Bess Myerson knows very well what is ahead of her—weeks of testimony, scores of witnesses testifying under oath about bits and pieces of her life, a life she would say was not much different from that of other famous daughters and sons of New York who have raised themselves up by learning how to always get their way.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now