Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

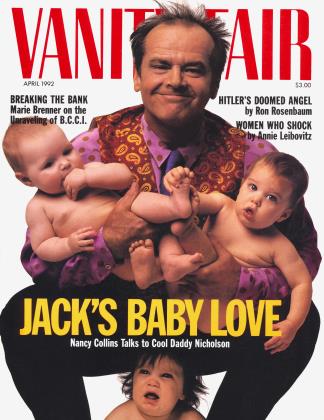

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCracking the mysterious cast of characters and transactions behind the B.C.C.I. scandal presented an irresistible challenge to esteemed Manhattan D.A. Robert Morgenthau— and possibly the crowning achievement of a long career. But the D.A.'s top investigators found themselves chasing after some surprising pieces of the puzzle, including a titan of the Democratic Party. MARIE BRENNER reports

April 1992 Marie BrennerCracking the mysterious cast of characters and transactions behind the B.C.C.I. scandal presented an irresistible challenge to esteemed Manhattan D.A. Robert Morgenthau— and possibly the crowning achievement of a long career. But the D.A.'s top investigators found themselves chasing after some surprising pieces of the puzzle, including a titan of the Democratic Party. MARIE BRENNER reports

April 1992 Marie BrennerFrom the beginning, the vast and complex case against B.C.C.I. has been one of warring truths and questions which doubled back on other questions, a $10 billion morass of international payola and fraud, byzantine characters and faraway places, dizzying shell games involving dummy bank accounts, forgeries, and alleged conspiracies to hide billions of dollars of international drug money. With the exception of NBC News, the networks have not lavished attention on the B.C.C.I. scandal; it has appeared to be a murky foreign thicket which defies sound bites, a quagmire with few American victims. "Who cares about these Arabs?" one network news producer told his reporter assigned to the case, although prosecutors believe tens of millions of dollars of bribes swept through Washington.

"B.C.C.I. serviced the financial needs of an industry "I have been asking myself, Where did I go wrong?

At times at recent press conferences in the office of the Manhattan district attorney, Robert Morgenthau, it was impossible not to be reminded of the atmosphere of the Watergate years. Reporters talked of "destruction of documents" and vast conspiracies, "White House scenarios" and "secret C.I.A. agendas." Journalists hovered around Morgenthau, who is canny about placing stories and beloved by the press. Now, with his relentless pursuit of "the Bank of Crooks and Criminals," he had become an international hero and heir to the tradition of Archibald Cox.

Morgenthau's office was bombarded by reporters' questions: Were Robert Altman and Clark Clifford, the two Washington superlawyers caught up in the B.C.C.I. scandal, trying to thwart the D.A.'s investigation? How was the Bahrain oil concession of George Bush Jr.'s Harken Energy connected to B.C.C.I.? Would Orrin Hatch's next Senate campaign be affected by his public defense of the bank's principals? What had B.C.C.I. accomplished by giving $8.8 million to Jimmy Carter's charitable foundation? Why would B.C.C.I. officials have sought to hire Henry Kissinger's consulting firm? Had former C.I.A. chief William Casey protected the criminal owners of the bank? Had George Bush's former chief of staff, John Sununu, spun the Justice Department and impeded Massachusetts senator John Kerry's hearings on the case? Why had Sununu's former aide Ed Rogers accepted a $600,000 fee from Kamal Adham, a front man for Agha Hasan Abedi, the fugitive Pakistani who was the criminal promoter of a drug lords' bank?

There are no hard, fast answers to many of the questions. Truth and facts are mired in what will be years of legal maneuvers. There is talk that the growing revelations of the B.C.C.I. conspiracies, once thought to be "a Democratic problem," as Bert Lance described it to me, could engulf George Bush's White House and influence November's presidential election. The finest legal minds in America, such as Robert Fiske, the former U.S. attorney from the Southern District, have been brought in to represent Clark Clifford and Robert Altman, who, as targets of Robert Morgenthau's investigation, face possible indictment.

Whatever the legalities and the loopholes of "the crime of the century," as the case is now called in the office of the Manhattan D.A., it is clear, as in the Watergate years, that somehow men of power and reputation have forgotten the difference between right and wrong. Studying the B.C.C.I. case, cynical prosecutors have despaired about the future of the country. "When the pattern of bribery is so established and so subtle that it cannot be proved in a court of law, then it is almost impossible for a democracy to function, ' ' Morgenthau's deputy chief of investigations, John Moscow, told me.

"To put this in the largest possible context, B.C.C.I. is a case study in the power of drug and oil money," says Morgenthau. "It all comes together in this bank. The amount of bribery is almost unprecedented."

At the very center of the American facet of the B.C.C.I. drama is Clark Clifford, for years an icon of the Democratic Party, who as a Washington lawyer and counsel to the bank made millions of dollars in fees and set up the legal machinery for B.C.C.I. to expand operations in this country. "I would not have touched [B.C.C.I. business] with a hundred-foot pole if I knew that there was any fraud or misrepresentation connected with it," he told Mike Wallace on 60 Minutes.

For friends of Clifford and Robert Altman, it was at first fashionable to say that Morgenthau should be worrying about the avalanche of murders and rapes in New York City, not spending his time trying to extradite con men from the Third World. Famous New Yorkers sent him angry letters vouching for Clifford's integrity. He was approached at his Amherst College reunion by a close friend: "Why are you going after Clark Clifford? You know he's done so much for the Democratic Party!" Pamela Harriman, who had been aided by Clifford in her rise in Democratic Party politics, defended him vigorously at dinner parties in New York and Georgetown. "Clark is a man of impeccable reputation and he will be exonerated," she reportedly said.

At a time in their lives when Clark Clifford and Robert Morgenthau should be picking up awards and tributes, the B.C.C.I. scandal has brought these two pillars of the Democratic Party into a direct confrontation with each other. It is as if fate has suggested a surprising finale: At eighty-five years of age, the hallowed Clifford suddenly finds himself facing an ignominious end, his memoirs discredited, his law firm disbanded, and his word doubted even if he is never charged with any crime. At seventy-two, Morgenthau, who for years lost jurisdiction and headlines to publicity-savvy former U.S. attorney Rudolph Giuliani, has obtained a last, best chance to reclaim the spotlight and score a searing moral victory for the legal system that he has upheld all these years.

Morgenthau is one of the great men of New York, the boss of an often overwhelmed law-enforcement system with 570 assistant D.A.'s prosecuting up to 30,000 drug cases a year and countless murders and rapes. He has often felt powerless in the face of street crime brought on by drugs. He knows that he could arrest dealers "until the cows come home," but none of it will do any good unless he gets the money-launderers who help keep the suppliers in business.

Morgenthau often hides his passions and his outrage at white-collar crime behind the mask of legal probity. He has a long face with a very high forehead, as if drawn by Modigliani, startling pale eyes, and the muted courtesy and perfect manners of his aristocratic German-Jewish forebears. His father, Henry Morgenthau Jr., was Roosevelt's secretary of the Treasury; his grandfather was an ambassador to Turkey under Woodrow Wilson. Men of power have little charm for Robert Morgenthau. As a child, he used to sit on F.D.R.'s lap when Roosevelt visited the Morgenthaus' Hudson Valley apple farm. When Robert Morgenthau was appointed United States attorney for the Southern District, he called his father to tell him the news. "Don't forget the Park Avenue crooks," Henry Morgenthau told his son. "They are the worst." For the D.A. and his prosecutors, the B.C.C.I. case is where all their passions and experience come together; it is a chance to prosecute "the Park Avenue crooks" and to illuminate the obscene misuse of the American banking system. It is a case of massive fraud and government influence peddling, with departments of law enforcement around the world allegedly jousting with one another as if scripted by Costa-Gavras.

In the same way that Robert Morgenthau hardly leaves a fingerprint as he exerts influence in New York, so too has Clark Clifford always operated swiftly and softly in the Washington world of favors and accommodation. It seems impossible to believe, yet they have never actually met, although both were close to John and Robert Kennedy. Morgenthau had run John Kennedy's presidential campaign in the Bronx and had, in turn, been appointed U.S. attorney when Kennedy took office. In Washington, Clifford had been placed in charge of Kennedy's transition team.

He was the family's personal lawyer, trusted to do "the cleanup work," as the author Richard Reeves phrased it.

Morgenthau and Clifford have sought different paths to power. Clifford is a legendary smoothy who parlayed his stint in the Truman White House into a hugely lucrative career as Washington's premier fixer and inside man. Morgenthau is, in his own circles, equally well connected. He is a judicial crusader who has spun plenty of his own webs. A good number of New York's federal and state judges were trained originally as Morgenthau prosecutors; it is said, perhaps apocryphally, that when judges annoy Morgenthau a few well-placed phone calls dispatch them to distant benches. He has loyalties everywhere, as many a political opponent has learned.

Morgenthau almost died during W.W. II when his boat was torpedoed; he threw his life jacket to another man and floated for hours in the water until he was rescued. He is a man with private areas of extreme passion and generosity. It is a given in the office that "the boss" will guarantee a job to any member of the Kennedy clan or anyone whose relatives suffered in the Holocaust. Morgenthau's influence can be felt all through the city and state—when he is irritated, he calls the governor or the mayor or picks up the phone and speaks directly to friends at The New York Times. He is part of the liberal world of New York where hardball is played with the right telephone call to the proper ancient friend.

The Clark Clifford of his recent autobiography, Counsel to the President, is a dedicated public servant who admirably served Truman by pushing through the recognition of the state of Israel. He writes extensively of his behind-thescenes efforts to end the Vietnam War as secretary of defense during the Johnson presidency, while hardly touching upon his lobbying activities, which began early in his Washington career.

Clifford radiates superiority. He has thick, wavy silver hair and massive eyebrows. His voice is authoritative, and so comforting it surrounds a listener like an eiderdown. He often arrives late to courtrooms and is inevitably the last man to speak at a meeting. He has shunned certain elite organizations, like the Council on Foreign Relations, as if he were a man apart. Several years ago he strolled into the Criminal Division of the Justice Department. "Where's your ID?' ' a guard demanded. "What is an ID?' ' Clifford reportedly asked.

A master of gesture and anecdote, he regales hostesses at dinner parties with stories of world leaders and knows how to make the right self-deprecating remark at the proper moment, as if he had analyzed the powerful effect personal charm could have on history. He often holds his hands with his fingers arched, a pose that his friends call "the Clifford steeple." When he stood with his client Bert Lance, who would later be indicted and acquitted on bank-fraud charges, one newspaper reporter observed that "Lance was accompanied by God."

After he testified before the Senate's hearings on B.C.C.I. in October, Clifford shook hands with all the aides and thanked them for their efforts, a theatrical gesture which seemed intended to display a preternatural calm. "It was like seeing a mask behind a mask," one staff member told me. "Clifford's public image was so overly cultivated that he seemed impervious to reality."

"I have been asking myself, Where did I go wrong?

Last December, B.C.C.I. pleaded guilty to numerous charges of racketeering, fraud, and larceny. As part of the deal, the bank agreed to forfeit all of its known American assets—$550 million—and pay a $10 million fine to New York State. "This is a great coup!" Morgenthau told me. "It will help us with subsequent indictments. It says to the world that [B.C.C.I.] has committed a crime and that we [in New York] have jurisdiction."

The Manhattan D.A. is weighing whether to charge Clark Clifford and Robert Altman with fraud and false-statement crimes involving B.C.C.I.'s clandestine ownership of an American bank. At the same time that Clifford and Altman were B.C.C.I.'s attorneys, they assisted a group of Arabs in a hostile takeover of a bank called Financial General, which they would transform into First American, the largest bank in Washington. It is now known that B.C.C.I. used Clifford and Altman to secretly acquire the bank. At stake in the investigation is whether Clifford and Altman served as front men for B.C.C.I., engineering a series of stock transactions without full disclosure to the Federal Reserve and to the superintendent of banks in New York. Clifford and Altman have steadfastly denied that they had any knowledge of B.C.C.I.'s agenda or its ownership of First American.

"The B.C.C.I. case raises questions about whether our system can be penetrated by anyone with enough money," Jonathan Winer, counsel to Senator John Kerry, told me. "Think about organized crime. Suppose it was Don Corleone and he says, 'I want people helping me out who are close to many presidents of the United States. I want former regulators and prosecutors.' [Don Corleone] couldn't get those people; he could only get Mob lawyers. B.C.C.I. didn't get Mob lawyers—it got the best and the brightest."

"There are still a lot of things we don't know," Morgenthau told me. "We don't know how the B.C.C.I.-First American relationship got started. We don't know how it got past the Federal Reserve. . . . What we are trying to nail down now is the ownership in First American and the possibility that there were false statements made by Clifford and Altman and the relationship between the Arab owners and the banks."

On the surface, the B.C.C.I. case seems to revolve around the complex criminal ambitions of Agha Hasan Abedi, who was determined to create the most powerful bank in the world. Abedi was a New Age charlatan with a charismatic personality. He ran seminars on Eastern mysticism for his employees and dispensed epigrams such as "Western banks concentrate on the visible, whereas we stress the invisible." He instructed his subordinates to do anything to please a client of the bank. Bank employees organized hunts for the great houbara bird of Pakistan and delivered prostitutes from the red-light district of Lahore. An American-based B.C.C.I. executive allegedly used to deliver ten-year-old girls to one member of a royal family in the Gulf.

Abedi roamed the globe meeting with world leaders. He reportedly donated £3 million to a foundation favored by the former British prime minister James Callaghan; it was Lord Callaghan who defended B.C.C.I. publicly and was said to have eased the way for Abedi to gain British citizenship. By 1975, B.C.C.I. had become the largest foreign bank in the United Kingdom.

In 1977, Abedi's global ambitions led him to America and Bert Lance, who had just been forced to resign in a financial scandal as President Carter's budget director. Lance was desperate for money and was looking to sell his controlling share in the National Bank of Georgia. Abedi helped Lance find a buyer, B.C.C.I. front man Ghaith Pharaon, and in 1982, Lance introduced Abedi to Carter. "Mr. Abedi and President Carter discovered they shared a mutual interest in the guinea worm and other Third World health problems," Bert Lance told me. Carter, as is now well known, toured the world in the B.C.C.I. jet and accepted an $8.8 million donation for his Global 2000 Foundation and the Carter Presidential Center. B.C.C.I. went on to open a number of American branches in the 1980s. Its guest logs were filled with the names of those it was hoping to enchant; visitors to the Miami B.C.C.I. office alone included President Bush's son Jeb, former Florida governor Reubin Askew, and Senator Bob Graham of Florida.

It is the dream of prosecutors that an informant will walk into the office with a perfect case guaranteed to ride the nightly news, but Robert Morgenthau had no idea in April of 1989 that Jack Blum, a plumpish, balding, middle-aged government investigator, was presenting him with the case that would bring them both great acclaim. Blum, then special counsel to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, knew he was onto a potentially massive case of money-laundering and bank fraud.

As an idealistic kid out of law school, Blum had nearly gone to work in the Manhattan Criminal Court. The D.A.'s office hadn't changed—it was still grimy and threadbare; street pimps, robbers, and drug dealers sauntered down the corridors, lost in the Manhattan court system. The smell of the D.A.'s office was overpowering, perfumed with the ineffable odor of "urine on the radiators," just as Blum remembered it.

Washington is filled with career legal investigators who do the dog work for ambitious senators and congressmen looking for scams and headlines, but Jack Blum is unusual. He is an intellectual, a voracious reader who often speaks of "the life of the mind." As a student at Columbia Law School, he was befriended by Hannah Arendt; he knows, as Arendt believed, that great evil often emerges gradually, through passivity and a series of ever increasing compromises. He is consumed with exposing government corruption.

What mistake did I make?" Clifford reportedly said.

For two years, Blum had been interviewing informants and witnesses for Senator John Kerry's Subcommittee on Terrorism, Narcotics, and International Operations. He was eager to learn how foreign policy affected America's handling of the drug problem. Almost by accident, he had run across the Bank of Credit and Commerce.

Blum was coming to see the redoubtable Manhattan district attorney very much as a last resort. It baffled him that the Justice Department appeared to have little enthusiasm for going after his quarry. B.C.C.I. was registered in Luxembourg and the Cayman Islands—havens of financial corruption, with their elastic rules and scant regulations—and based in London; it was known to have done business with Arab terrorists (including, it would later emerge, Abu Nidal), as well as the Colombian drug trade; and it owned a large Colombian bank tied to the Medellin cartel. Just as puzzling to Blum was how a man like Clark Clifford, who had long prided himself on his access to presidents, could be representing B.C.C.I.

For the Senate hearings, Blum had reeled in some prime beauties as witnesses and informants, including two highly placed B.C.C.I. executives. They spoke of the many international players involved in B.C.C.I.'s money-laundering. Blum had even hauled in Manuel Noriega's own counsel general, based in New York. One day Noriega's man sat down and drew Blum an elaborate chart entitled "Noriega's Criminal Empire." There on the diagram was the bull's-eye—B.C.C.I., Noriega's bank of choice.

"These were people in businesses that are as ugly as it gets," says Blum of Abedi and his cohorts. "It was straightout criminality in terms of laundering drug money, hiding drug assets. It was the white-collar side of the drug trade. What we were looking at in B.C.C.I. was an organization that serviced the financial needs of an industry that was destroying a generation of American kids."

At the street level, B.C.C.I.'s managers had worked out an arrangement with a group of drug dealers. Cocaine brought into the United States was sold; the cash was deposited in B.C.C.I. accounts in low-denomination money orders and C.D.'s to evade tracing. Withdrawals from these accounts were then wired offshore, and B.C.C.I. earned a percentage of the take for laundering the money. According to testimony, one trafficker alone laundered $200 million a month, mostly through the U.S. branches of B.C.C.I. In one small example, two plastic bags that contained at least $145,000 in $1,000 money orders later came to the attention of investigators from the Federal Reserve. "I wondered when you were going to notice this," a B.C.C.I. bank teller told the Feds.

As if it were the rum circuit of Colonial times, B.C.C.I. was also masterful at exporting cash. "Satchels of drug money were put on certain airlines associated with Arab interests, and the cash would then be deposited in Saudi Arabia," one prosecutor told me. "In Saudi Arabia, the bank would exchange the cash for gold. The gold would then be moved by ship to India, where there is tremendous jewelry manufacturing. The gold would be sold and that cash would go into B.C.C.I. operations there."

Blum told Morgenthau that he had been helping the U.S. Customs Service and the Drug Enforcement Administration tape informants they had picked up in Florida. The Customs Service was often looked down upon by prosecutors as the kindergarten of law enforcement, but in Tampa the agents were operating magnificently. In fact it was a customs agent, Robert Mazur, who produced the first proof of B.C.C.I.'s money-laundering, as part of a two-year undercover operation called C-Chase.

Blum had what every case needed for a successful prosecution: the warm bodies, the actual B.C.C.I. witnesses, who were willing to talk to the Tampa federal prosecutors.

"I said to the prosecutors, 'Guys, here is something important. Listen, [the witnesses] will help you.' " Blum was offering a case that could make a young prosecutor's entire career. He was astonished by their tepid reaction: the local federal prosecutors indicted B.C.C.I. on money-laundering charges, then made a deal for a guilty plea contingent upon no further corporate prosecutions in Tampa.

The more Blum prodded, the less anyone in the Tampa U.S. Attorney's Office seemed interested in pursuing other charges against the bank. He could not understand why Tampa was not picking up the ball. (Tampa prosecutors contend that Blum's witnesses were, in fact, unwilling to testify at the time, and that they needed more time to build the case.)

(Continued on page 260)

(Continued from page 173)

Blum knew there were many other areas to explore—he had been told by a witness that B.C.C.I. was the secret owner of First American. Now he became convinced that he was being thwarted by peculiar maneuvers on the part of Clifford and Altman. He also believed that something untoward was going on at the Justice Department. The number of agents assigned to help him investigate the B.C.C.I. case had mysteriously dwindled; witnesses were telling him they had heard B.C.C.I. lawyers were bragging in the London office that they had torpedoed Senator Kerry's hearings. When Florida B.C.C.I. executive Amjad A wan was subpoenaed, he told an undercover agent that Altman was advising him to flee the country. Blum was convinced that Clifford and Altman were stalling delivery of documents that he had subpoenaed for the Senate. They were, he believed, "feigning complete ignorance of what it was we were going after.

"The thing that infuriated me was that, at the same time we had a subpoena out, there were people inside [B.C.C.I.] who were telling us that documents were being shredded in the bank's Washington office because we had issued a subpoena. That angered me greatly,'' Blum told me.

"I said to Morgenthau, 'This is the biggest bank fraud in the history of the world. You have a bank that has no capital—in essence it has borrowed money from itself to create capital. It has a whole system of fake shares and fake deposits. What they have done is conceal the ownership of other banks and falsify their statements."

Morgenthau sat at the desk that day smoking his cigar, leaning back in his frayed blue leather office chair. The D.A.'s desk is a legend with court reporters; it is covered with a jumble of motions, invitations, subpoenas, pleas, toddlers' paintings, address books, menus, and resumes. Morgenthau's papers tower in great unruly drifts, as if they dated back to Abe Beame's administration. At press conferences a tattered plastic sheet is thrown over the whole mess. In fact, Morgenthau's inner sanctum is a charming dustheap of memorabilia, a setting out of film noir. The walls are covered with awards and framed letters from F.D.R. and Lord Lothian to Henry Morgenthau. There are fake Dufy paintings Morgenthau once rounded up in an art-fraud case, and photos lovingly inscribed by all the Kennedys, as well as pictures of Morgenthau's two young children and his second wife, Lucinda Franks, a forty-five-year-old former New York Times reporter who won a Pulitzer Prize.

"Blum said, 'I don't think this is going to be prosecuted,' " Morgenthau recalls. "I said, 'Is there evidence of moneylaundering through New York?' and he said, 'Yes, and in addition there is evidence that B.C.C.I. controls First American.' He said, 'If you don't do anything about it, the whole thing is going to be dropped.' "

Michael Cherkasky, Morgenthau's chief of investigations, was incredulous. "Blum's story was ridiculous!" Cherkasky later told me. "[He said] the entire Third World was involved and that they had bought and sold entire governments and maybe some United States officials. It was a fascinating tale—this guy was telling us the world was corrupt!"

Cherkasky, whose father was once the head of Montefiore hospital, has known Bob Morgenthau his whole life. Now forty-one, he is as close to the D.A. as one of his own sons. "I said to Morgenthau, 'Boss, do you want to do this? I don't think it is going anywhere.' "

Cherkasky's tone was flat—he was mired in a complex prosecution of John Gotti and he envisioned all the hideous problems that could come with a case such as B.C.C.I., the years of unanswered subpoenas, the Saudi witnesses cloistered in the Third World, the documents that would never appear from the Cayman Islands to Pakistan. And Cherkasky worried: Where was the jurisdiction? How could a local D.A. afford the cost of a worldwide investigation? How could the New York County prosecutor indict an international bank of moneylaunderers? "If New York is the banking center of the world and the money is laundered through here, there is our jurisdiction," Morgenthau said that day, but his motivation may have been more complicated. Here at last was his chance to outdo his old headline-grabbing adversaries in Rudolph Giuliani's former office at the Southern District. "If the United States attorney is not doing it, I'm doing it," Morgenthau added. He turned to Cherkasky. "Who do we want to do it?"

"There's only one guy in our office to do this: John Moscow," Cherkasky said, speaking of his top investigator.

Moscow, like Cherkasky, has long and special ties to his boss. His father, Warren Moscow, was for many years the chief political correspondent for the Times, and later was director of the Housing Authority for Mayor Robert Wagner. Moscow, forty-three, has the hooded eyes and knowing demeanor of a man who understood by the time he was in fifth grade where every body was buried. He went to Harvard Law School, but has come to terms with earning $90,000 a year as a prosecutor, because he enjoys solving complicated crimes. In the office, Moscow is considered a brilliant strategist and moral "zealot." He is also a devoted family man who met his wife after she served on the jury of a case he was trying. Almost nothing surprises him. His favorite expression is a deadpan "Very interesting." Moscow's speech patterns are often so dense that reporters joke they need subtitles to understand him. When he talks, he often rocks back and forth, as if the pressure of such deliberation causes an involuntary body tremor.

Over the next two years, against every obstacle, Moscow would almost singlehandedly do the detective work that would help Morgenthau crack the B.C.C.I. case. "Morgenthau and Cherkasky called me and said that Blum had said B.C.C.I. was corrupt and that it owned First American. They said they wanted me to take a look at it. So I said, 'Well, other than the fact that the bank is dirty, is there anything more that you want? Any other information you guys have?' Their answer was 'Not a whole lot,' " Moscow told me. "The boss did not have a clue how big this case was going to be."

Robert Morgenthau's skill as a prosecutor rests on complex white-collar investigations. He has the ability to look at many unrelated transactions—bank records, stock movements, and phone logs— and perceive a pattern of activity that no one else will see. Most prosecutors take evidence, pull the lawbook off the shelf, find a statute that fits the crime, and file an indictment. Morgenthau often doesn't wait for a crime to appear—he intuits when someone is up to no good.

Soon after Blum left his office, Morgenthau looked up First American in Moody's stock guide. This was his best hope at jurisdiction: First American had forty-three branches in the state. "The stock in First American Bankshares was owned by a Delaware holding company, which was owned by a Netherlands holding company, which in turn was owned by a holding company in Curasao," Morgenthau told me. On top of all of these names was the name Clark Clifford. Morgenthau was well aware of his reputation as a point man for presidents. That day, staring at Moody's, Morgenthau knew "somebody was trying to hide something."

Morgenthau would later have lunch with the head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. "How much money passes through New York in a single day in wire transfers, about one and a half to two trillion dollars?" he asked. "Try three and a half trillion on a quiet day," the head of the Federal Reserve replied. "If someone is trying to hide a couple of hundred million dollars a day in the money stream, here was how to do it," Morgenthau later told me.

John Moscow started with a very simple premise. "We kept asking one basic question: 'Who owns B.C.C.I. and where did the money come from?' We never got to the advanced questions. We got stuck on the simple questions and on 'Who owns First American?' " One day that spring of 1989, a British investigator was in New York. By chance Moscow ran into him at John Gotti's old hangout, Antica Roma, an Italian bistro near the courthouse. ''What do you know about B.C.C.I.?" he asked the investigator in the small, dim room. "They are the world's biggest money-launderers," the investigator said. Moscow spoke to contacts at the bank clearinghouses in New York: "The word 'crook' came up a lot."

It was a turbulent time in the D.A.'s office. A few days after Blum's visit, a young female investment banker from Salomon Brothers was raped, brutally beaten, and left for dead in Central Park. Morgenthau and his chief of sex crimes, Linda Fairstein, were besieged by reporters. Moscow was busy, too, preparing a complex murder-and-fraud case, and B.C.C.I. was still a distant mystery.

Then, in July, a conference in Cambridge, England, on money-laundering, organized by the Commercial Crime Unit of the Commonwealth Secretariat, caught Moscow's attention. One case involving B.C.C.I. was on the program. He and a colleague hopped on a plane.

Soon after Moscow arrived in Cambridge, however, a new program was suddenly announced for the seminar— B.C.C.I.'s money-laundering history had vanished from the schedule. Moscow quickly learned that a high official from B.C.C.I. was in Cambridge. "I went to the director's office and I said, 'How come this speech is not being given?' and they said, 'It's just not.' There was no point in making a scene." But Moscow left England convinced, as he later put it, that ''the fix was in."

Back in New York, Moscow interviewed an informant who gave him startling news. ''He told me that B.C.C.I.'s owners were all nominees. . . . [He said that] Abedi had gone around the Gulf and gotten these sheikhs, some of whom didn't have a pot to piss in, to be nominee owners. He got them to agree that he could use their names on anything as long as they were not economically liable. He didn't ask them to put money in it, he just said, 'Let me use your name.' " Moscow immediately seized on this information. Phony ownership—and, later, phony loans—was the classic way a crooked bank perpetrated a fraud.

Moscow contacted the Serious Fraud Office in England, requesting documents from B.C.C.I.'s London headquarters. ''Will you help us?" he remembers asking. But the Serious Fraud Office wanted nothing to do with the allegations of a local prosecutor. ''They told me that they had no interest."

Moscow then called Altman's handpicked lawyers, Lawrence Barcella and Lawrence Wechsler—''the Larrys," Moscow calls them—who had negotiated B.C.C.I.'s money-laundering plea in Tampa. Barcella had persuaded the bank officials to avoid a trial. ''You were going to have a bunch of dark men with funny accents facing a bunch of old people," he told them, according to James Ring Adams and Douglas Frantz's new book, A Full Service Bank. Moscow said to Barcella and Wechsler, " 'We would like to know who owns this bank. ' They did not want to answer. I said I had heard that there was a problem with the capital structure of the bank and I wanted to know, 'Does this bank have the money that it represents to have?' They told me that they did not know if they were permitted to disclose the existence of the capital records; they did not know if they existed, and they did not know if there was any evidence of who had purchased the stock." (Barcella remembers a different exchange: he says he told Moscow that, as far as he knew, the bank's audit records were in London and subject to bank secrecy laws.)

Wechsler and Barcella, now in private practice, had worked for some years in Washington as federal prosecutors. Wechsler is a childhood friend of Robert Altman's and often spends his Sundays watching Redskin games at the immense estate of Altman and his wife, Lynda Carter. Wechsler and Barcella represent the old-boy network; they are part of an endemic Washington ''revolving door" culture. (Barcella, for example, was first a star federal prosecutor who went after renegade ex-C.I.A. agents; later, as a whitecollar lawyer, he represented Antigua in its own mini-B.C.C.I. scandal, the shipping of machine guns from Israel to the Colombian drug cartel; he is now chief counsel for the House investigation of the ''October Surprise"—a case in which a key figure banked at the London office of B.C.C.I.) Moscow might be trying a case against men who were piped into the thoughts and secrets of friends in the Department of Justice. The two Larrys would know every loophole and soft spot.

But Moscow now knew he was onto something significant. ''When bank lawyers tell me that they don't have a record of its capital infusions or the stock-transfer records and can't say that it kept records of its deposits. . . We are not talking about the Chase bank going back to 1799—and they probably would have had all those records! We are talking, at that point, about a seventeen-year-old bank!"

A few months ago at the home of Clayton and Polly Fritchey, Clark Clifford was honored at a small dinner with close friends. Only ten people were invited to the Fritcheys' house, which had long been an adjunct social headquarters for the intellectual elite of the Democratic Party. The dinner party was intended to buck up an old friend. The Fritcheys knew that Clifford had been keeping to himself, immersed in the scandal that threatened to ruin his reputation.

The Fritcheys aftd the Cliffords went back forty years or more in Washington politics; they had seen scandals come and go. At the appropriate moment, Clayton Fritchey, almost ninety years old, stood up to give a toast. He was careful to talk about the past, not the present; even Clifford's intimates were confounded by his role in this ugly mess. But when Clifford stood up to respond, he seemed compelled to speak about his problems. His eyes filled with tears. ''I have been asking myself over and over again, Where did I go wrong? What mistake did I make? Have I lost it? What clue did I overlook?" he reportedly said.

Alongside his skills as a corporate lawyer, Clark Clifford has for years relied on solipsism. The essence of his Washington law practice has always been his name and his Rolodex. He has made certain phrases his signature: ''based on my years in government"; ''based on my trust." In 1981, when he stood before the Federal Reserve to vouch for the acquisition of First American by a group of Arab investors, he invoked every bit of his personal prestige. Testifying before the Senate Subcommittee on Terrorism, Narcotics, and International Operations last October, Clifford again stressed his credibility. ''My word has been important here for a great many years. . . and I ask you to take it."

''Put yourself in the minds of the men of the Federal Reserve," the former U.S. comptroller of the currency John Heimann told me. "Clark Clifford comes in and he says, 'You have my word that B.C.C.I. will have nothing to do with First American.' What could they have said? 'I accept your word, sir,' or 'Are you a liar?' "

Before the Senate subcommittee Clifford said, "At one source that I checked, they indicated that the United States was sending, at the time, $70 to $80 billion a year for the purchase of crude [oil] from the Middle East. And as far as our Government was concerned, it would be their preference that as much of the money flow back to the United States as possible ... So that there was no objection leveled at the time to [the] effort by this group of Middle Easterners to acquire an American bank."

When Clifford attempted to explain his failure to suspect any wrongdoing by B.C.C.I., his testimony strangely echoed his words at the Fritcheys' dinner. "You may rest assured that I have combed my memory over and over and over in that regard. I do not recall an instance, I do not recall any act on the part of anybody, I do not recall any evidence being brought to our attention which would alert me to the criminal conspiracy that was going on.

"At the same time, I still have an uncomfortable feeling about it. Why didn't I sense it in some way? I would have wanted to. I have sensed it in other instances in past experience. So that is a purely personal approach to it, but it helps you understand it better."

A few days earlier, Abdur Sakhia, the former head of the Miami B.C.C.I. office and one of the most important B.C.C.I. officials in the country, had been questioned by the Senate subcommittee.

Senator Pressler: Now, in 1984, did you learn of reports that BCCI was involved in drug money laundering? I believe you testified that you did, through Senator Paula Hawkins [of Florida]. However, can you describe how you learned of BCCI's involvement and what you did about it?

Sakhia: Sir, in sometime in. . . 1984,1 got a call from Mr. Abedi on Saturday morning, very early Saturday morning, at my apartment in Miami.... He told me that Senator Paula Hawkins, along with some other Senators or officials, had visited Pakistan and met General Zia, and she had told to General Zia that besides the smuggling of drugs from Pakistan etcetera etcetera, there was also money laundering being done by a Pakistani bank out of Grand Cayman.... So then General Zia blew his top and said, "Look, you are spoiling our relationship with the U.S... .and our aid is in jeopardy. Why are you doing this?"

Sakhia testified that he had rushed to Washington to try to calm Senator Hawkins. When he arrived, however, she seemed to have lost interest in the affairs of B.C.C.I. and dismissed him after a short talk. She then arranged for Sakhia to meet with a representative from the Justice Department and another from the State Department. They told Sakhia that B.C.C.I. was "not under investigation." He wondered why, but he noticed that by late 1985 Abedi had become confident that the bank would be able to expand in the United States. "My own impression," Sakhia testified, "is that a deal had been struck somewhere. ''

"Did anybody put that idea in your head?" asked Senator Kerry.

"No," he said. "Again, in that culture, you understood a lot of things, whether you were told or you were not told, but you understood a lot of things." Sakhia would later learn that his hunch about a deal had been correct: under William Casey, the C.I. A. was using B.C.C.I. as a conduit for covertly supplying arms to the Nicaraguan contras and the Afghani resistance. And Senate investigators would later find a 1985 check from B.C.C.I. to General Zia in the amount of 40 million rupees ($2.5 million).

By the mid-1980s, Sakhia was meeting frequently with Altman. On one occasion in 1988, he brought the new head of the American desk in London, Dildar Rizvi, to see Altman about B.C.C.I.'s plans for expansion in California. Afterward, Rizvi asked if Clifford was in the office, as he wanted to "pay his respects." The exchange was quick. "Mr. Rizvi briefed him that now we were going ahead with our plans in California and Mr. Clifford . . .said little jokes, political jokes, other jokes. And he said, what strikes out in my mind is, 'Mr. Rizvi, welcome aboard. We will tell more lies now.' " At the time, Sakhia testified, he thought Clifford was joking, "but in the present context it's no more a joke."

In meetings with the Federal Reserve, Clifford referred to Kamal Adham deferentially as "His Excellency."

Clifford later attacked Sakhia's remark. "It was an outrageous statement," he told the Senate subcommittee. "It is grotesque. It is totally and categorically false."

By the late 1970s, Clifford knew his way around the Middle East. It was a time in Washington when there was a great deal of concern about foreign bribery; Clifford was already acting as counsel to B.C.C.I. when he agreed to represent McDonnell Douglas in a 1978 case involving massive bribery to Pakistan. McDonnell Douglas was accused of bribing a relative of President Ali Bhutto to obtain contracts to build planes for the state-owned Pakistan International Airlines. Clifford, a childhood friend of the chairman of McDonnell Douglas in St. Louis, was called in to strike a corporate plea deal.

Although there was no direct link between McDonnell Douglas and B.C.C.I., there were odd crossovers and coincidences which suggested Clifford's awareness of the possible consequences of doing business in Pakistan and the Middle East. Kamal Adham, the alleged bagman for bribes made in the Middle East by Boeing, McDonnell Douglas's arch-rival, was already a Clifford client and would later become a principal shareholder of First American. A relative of King Faisal of Saudi Arabia and head of the Saudi secret police during one of its most repressive periods, Adham had also been the paymaster for Anwar Sadat and, according to investigators, was used by the C.I.A. for information gathering. He had a courtly manner and was often treated like a pasha; in meetings with the Federal Reserve, Clifford referred to Adham deferentially as "His Excellency." In the same meetings, Clifford characterized Adham as "a prominent businessman in Saudi Arabia" and said, "I have not heard one whisper of criticism against this man."

How did a lawyer who had once advised presidents wind up representing a shady power broker like Kamal Adham? Clark Clifford has the braided personality of a man of contradictions. He lives relatively modestly and prides himself on wearing an old fedora and eating a tunafish sandwich for lunch at a Peoples Drug store near his office. At the same time, he has long seemed to charge more than any other lawyer in Washington. He virtually invented the notion of modem lobbying— when he left the Truman White House, one of his first clients was Howard Hughes. "It was rather obvious" that Clifford used the contacts he made in the White House to build up his career as a superlawyer, Harry Truman's daughter, Margaret Truman, told me.

Clifford moved through Washington with the grace of a dancer. "Washington is a city of minefields," he used to tell his clients. If a client was in an ethical dilemma, Clifford had a favorite bromide: "He would say, 'You don't stop to think about whether or not this violates the criminal code, just think about how it would play on the front page of the Times or 60 Minutes,' " said a longtime friend.

The former Israeli ambassador Abba Eban, who knew Clifford in both the Truman and Johnson administrations, remembers an "informal young man" serving President Truman fearlessly, standing up to General George Marshall's resistance to recognizing Israel. Twenty years later, when Eban went to see Clifford, then Johnson's secretary of defense, he was astonished by the change in his personality. Clifford was "rather stiff," Eban told me. "I had to say, Mr. Secretary, this, and, Mr. Secretary, that. . . " Eban was startled at how Clifford's job had changed his attitude, as if there were no underlying strong identity.

"The French have a phrase, deformation professionnelle, " Eban told me. Loosely translated, it means "your job defines your perspective. With [Clark Clifford], I have never seen a more dramatic example of that." He was a man, Eban told me, who decided to "worship his master."

Nevertheless, by the 1960s, Clifford had become a man of immense power and prestige. He was called "Superclark" and delighted in his role as presidential adviser. He was a member of the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, and even before he became secretary of defense, Clifford was often in Lyndon Johnson's White House, advising him privately about the Vietnam War. As the public mood in the country became overwhelmingly violent and sour, Clifford urged the president to announce a cessation of all bombing. When Johnson took his advice, Clifford believed it was his finest hour.

It has become received wisdom for Clark Clifford's friends to explain his involvement in B.C.C.I. as the last gasp of an old man desperate to hang on to power. A popular theory is that Clifford and Altman became "prisoners of the enormous fees" they were earning in their dual— and perhaps conflicting—roles as First American bank executives and counsel to B.C.C.I. In one year alone, they received $4 million in fees. Clifford's friends blame Robert Altman for leading him, as one told me, "down the garden path," as if Clifford, meeting his Eve Harrington, had lost his cunning.

Investigators have another theory of Clifford's involvement with Abedi and Kamal Adham: it was, in Washington terminology, not a payoff, but a "bundle" or "package" in which everyone operated according to aligned interests.

Clifford had strong ties to the Carter administration, which was attempting to negotiate peace talks between Israel and the Arab world. And on Labor Day 1977, Jimmy Carter called Clifford with a problem, according to The Washingtonian. "My budget director, Bert Lance, is in trouble," Carter told him. Lance was being accused by a Senate committee of running a bank in Georgia that was, according to the article, "rife with insider deals, kited checks, and six-figure overdrafts." Clifford assigned "Lancegate" to his star junior colleague, thirty-oneyear-old Robert Altman, who viciously attacked the integrity of the senators. The press bannered the hearings, and, surprisingly, Lance and Altman emerged as winners, although Lance was forced to resign.

Soon after Lance and Altman triumphed, Lance brought Abedi into the offices of Clifford's law firm. When Clifford was introduced to Abedi, he perhaps met his final and ultimate master. "Mr. Abedi was interested in establishing a presence in the U.S.," Bert Lance told me. "He had some other Washington law firm representing him, and I just felt that. . . Mr. Clifford could serve his purpose well. I introduced them. Mr. Abedi was impressed with Mr. Clifford and Mr. Clifford was impressed with Mr. Abedi." Moreover, each needed something from the other—Abedi, the access that Clifford's reputation could buy, and Clifford, Abedi's Middle Eastern webs. With Abedi and Adham, Clifford could operate in the back channels, as if he were still a shadow member of the government.

Kamal Adham, according to investigators, persuaded the other Arab leaders to allow Egyptian president Sadat to participate in the 1978 Camp David peace talks, the signal achievement of the Carter presidency. Here was a perfect Washington package: In order for Sadat to attend the peace talks, "he needed to be sure he wouldn't be isolated and cast out by the rest of the Arab world," according to an investigator. "That assurance is part of what Adham could deliver." In return, government regulators would allow the Gulf sheikhs to invest in First American bank.

Over and over, Clifford would later repeat, "I have talked to people at the highest levels of government and they want this to happen." Pressed by Senator John Kerry in the most recent hearings about whom exactly Clifford meant by the "highest levels of government," he waffled. Someone at the State Department, someone at the Commerce Department. Altman's answer was equally opaque: he recalled "a conversation we had with Arthur Burns. . .who was not then the chairman of the Federal Reserve," and another conversation with Senator Stuart Symington, an old friend of Clifford's.

An unexplained mystery of the B.C.C.I. affair is the relationship between the C.I.A. and Abedi. In testimony before the Senate, Robert Altman said he was aware "that the C.I.A. has maintained accounts at First American," but Clifford denied any knowledge of specific C.I.A. connections he was questioned about.

Starting as early as 1978, government officials were aware of B.C.C.I.'s controversial reputation. Bert Lance had a strong early warning that B.C.C.I. might be a troublesome client for Clifford's law firm. In the early 1980s, Lance was driving Abedi back to his hotel from a conference on the Middle East that Jimmy Carter had organized at Emory University. "[Abedi told me], 'I think there is something I need to tell you about, just so that you will be aware of it.' He said that ever since Ronald Reagan had been sworn in as president he had been on the C.I.A. watch list and that his every movement was under surveillance. [He said that] when he came into this country many times he was hassled and put into holding rooms at different points of entry."

Afterward, Lance testified, Abedi never spoke of the problem again. Around the same time, Abedi and Casey began meeting secretly at the Madison Hotel in Washington, according to NBC News. Like Sakhia, Bert Lance was convinced that William Casey had made a deal with Abedi that would shield B.C.C.I. from investigation as long as Casey was running the C.I.A.: "They didn't become crooks until after Casey died.''

It is often said that Bob Altman was the son Clark Clifford never had, but, more than that, they appeared to be alter egos. "I think Mr. Clifford saw a lot of himself in Bob," Bert Lance told me. From the beginning, Altman was dazzled by Clifford. "Robert had never seen such a high concentration of savoir faire," a friend recalls. The protege seemed to exhibit his own brand of deformation professionnelle. Perhaps unconsciously he even began to imitate Clifford's gestures and stentorian tones. He affected dark doublebreasted suits. One reporter who interviewed him during Lancegate observed, "Altman seemed like he was wearing his father's suit."

As a child, Altman had been a brainy "nerd," a close family friend remembers. His parents were highly competitive lawyers who lived in the pleasant Washington neighborhood of Cleveland Park. As a law student at George Washington University, Altman worked at Clifford & Wamke and later joined the firm.

Altman led the takeover battle to buy Financial General bank for the group of Arab businessmen who became the nominal owners. They changed the name of the bank to First American, and, with Clifford and Altman's assistance, got government approval to open its doors. Clifford became the chairman of the new bank, and Altman the president. Clifford's wife, Mamy, would later tell a close friend how impressed her husband had been with the perks of the bank job. "One of the things that impressed him the most was the very large office and two huge limousines he received," she reportedly said. When Clifford resigned as chairman of First American, in the wake of the B.C.C.I. scandal, he was said to have asked Nicholas Katzenbach, the new head of the bank, if he could buy one limousine.

Summer 1990: As the scope of the B.C.C.I. investigation grew, the Morgenthaus' Park Avenue apartment became "the D.A.'s office, Upper East Side," says Lucinda Franks, who was working at home, trying to finish a novel. "There were more and more secret phone calls. Many people around the country who could not talk to their law-enforcement agencies could speak to Bob at home." People were constantly calling Morgenthau on a private line. That August, on Martha's Vineyard, Morgenthau "would frequently disappear for hours at a time to talk with secret sources," Franks told me.

Back at the office, John Moscow hit on one of the first pieces of hard evidence of bank chicanery. It was, ironically, a small-time Mob loan that First American's holding company had arranged for a restaurant in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Combing through reams of documents, Moscow noticed peculiarities in several accounts. "We issued subpoenas for six accounts," he said. "There were three Mob-related loans and two related-party transactions, a form of fraud where people are loaning money to themselves. Three Mob loans alone seemed to justify the indignation at B.C.C.I."

Moscow was also trying to understand the complicated ownership of B.C.C.I. and to unravel what had gone on in a Tampa customs investigation. He had been told that, a few years earlier, a Tampa government investigator had heard hours of undercover tapes concerning the true ownership of First American. The investigator had flown to Washington to interview Clifford and Altman. Altman had hedged with the investigator; he had then attempted to make an appointment with Clifford, but Clifford had refused to see him. The Tampa investigator had then received a phone call from his boss. He was told that he was doing the money-laundering investigation only and not to follow this up.

From the beginning, Altman was dazzled by Clifford. "Robert had never seen such a high concentration of savoir faire."

Later, a crisis had developed in Tampa around the undercover operation of Tampa customs agent Robert Mazur. Mazur testified to the Senate that massive amounts of money moved through B.C.C.I. in Tampa from Colombian drug traffickers. He believed that "there were records in the Miami [office of B.C.C.I.] that would have related to, at least in part, the association between BCCI, First American, and the National Bank of Georgia." But as Mazur tried to press the federal government to prosecute, strange things began to happen, which threatened his cover: federal warrants in Detroit described the undercover operation in detail; a Houston surveillance was apparently compromised; in New York City, undercover agents were detected by Colombian traffickers, as if they had been tipped off. "I think there were times when a pause occurred [in the investigation] because of the apparent influence of someone," Mazur testified.

Not only would the Tampa U.S. attorneys let Mazur down, they would also thwart Morgenthau's investigation. By the summer of 1990, Moscow had grown frantic trying to obtain hundreds of documents from Tampa. He turned to Morgenthau for help. A series of faxes traveled back and forth between Tampa and New York, and, Michael Cherkasky remembers, Robert Genzman, the Tampa U.S. attorney, "sent letters that were insulting to Morgenthau." In one instance Genzman wrote Morgenthau that if he gave him any papers Morgenthau would have to agree "to obey the laws of grand-jury secrecy," says Cherkasky. "No one has to tell Robert Morgenthau to obey the laws." In private, Morgenthau commented, "That S.O.B. is obstructing me. We are going to do this case anyway."

That same summer, John Moscow called Robert Altman. He was surprised when Altman answered his own telephone at the office. "We're doing an investigation and we'd like to talk to you," Moscow told him. "I'll have to get back to you," Altman replied. Soon after, Moscow learned that Altman had hired Robert Fiske, the former United States attorney for the Southern District and one of the top litigators in the country.

Fiske then appeared in Moscow's office. "If you want to meet with my client, you will have to give him immunity," Moscow remembers Fiske telling him. "I said, 'You have to tell me what I am giving him immunity for. What has he done that is wrong? I am just doing an investigation.' " "He hasn't done anything wrong," Moscow remembers Fiske saying. "I'll give him that much immunity," Moscow replied. Fiske has a different recollection: "I remember telling John that I had just come into the case and as far as I knew my client had done nothing wrong."

Robert Altman was now appearing to pull every lever he could. In September of 1990, after Clifford and Altman had been asked to testify by Senate investigators, a B.C.C.I. lawyer wrote a confidential memo for the files: Altman and another B.C.C.I. attorney, it said, were ''doing everything within their power to call in 'political markers.' Consequently, it may be that Altman. . . will succeed. . . and not end up testifying before the Kerry Committee."

That autumn, Moscow learned that the Bank of England, suspecting fraud, had asked Price Waterhouse to conduct a special audit of B.C.C.I. The audit showed billions of dollars that had vanished, false accounts, rotten loans, and frauds so large it was impossible to calculate their size. The Price Waterhouse accountants went to Luxembourg to discuss their findings with representatives of the Abu Dhabi shareholders, for they would have to cover the bank's losses. (Soon after, Clifford and Altman resigned.) At the same time, the accountants sent a copy of the audit to the Bank of England. Subpoenas flew out of Manhattan Criminal Court as the prosecutors tried to get their hands on the Price Waterhouse audit. By this time, Moscow was working with the Federal Reserve, which was also investigating B.C.C.I.

''I was very much the young kid with the stick prodding the elephant," Moscow told me, referring to the Federal Reserve. "We were hitting a brick wall— the Bank of England wouldn't give us anything, Price Waterhouse couldn't give us anything."

In November, the Federal Reserve finally demanded a copy of the B.C.C.I. audit, but Moscow still needed cooperation from the British. It was then that Robert Morgenthau, without federal assistance, pulled in his own nets. He contacted Eddie George, the deputy governor of the Bank of England. Morgenthau reminisced about his time in England during the war. "They spoke about people they knew in common," says Moscow. "Morgenthau told George, 'We are going to charge this bank,' " Cherkasky recounts. " 'And when we charge them, you are going to be looked at publicly. We would like to be able to say that the Bank of England helped us.' "

Morgenthau was now in high gear. He called Steve Kaufman, a prominent lawyer and close friend who had once worked for him and now represented Price Waterhouse. Kaufman in turn persuaded the English accountants to come to New York and meet with the D.A. Once he had them in his office, Morgenthau put his arm around the audit partner and showed him the framed letters from Lord Lothian to his father. "In no time the Price Waterhouse accountants were on board and helping," Kaufman told me.

Acting on a tip, investigators from the Federal Reserve took off for Abu Dhabi— and found a windfall of bank documents stacked in crates. After rummaging through the records, they called Moscow. "I think we have found what we are looking for," one said. What they had found were documents that showed the ownership link between B.C.C.I. and First American.

With Thornburgh gone, Justice now has about fifty-five staff members and seven grand juries assigned to the B.C.C.I. case.

In March of 1991, the Fed shut down B.C.C.I. in the United States. In New York, Morgenthau was moving closer to his first indictment. His office would soon be crowded with Peruvian officials who were ready to testify that B.C.C.I. had paid $3 million to obtain a foothold within Peruvian banks. Although the Federal Reserve had been carrying the oar for the investigation, that spring Morgenthau discovered he needed further cooperation from the Justice Department.

But when the Manhattan D.A.'s investigators asked the Tampa prosecutors to release the B.C.C.I. tapes, they were told "those tapes do not exist," according to Cherkasky. "They not only lied to us, they lied to the Federal Reserve," Morgenthau told me. "We would fly assistants to Tampa and they would come back empty-handed. ... I have never been lied to by another U.S. Attorney's Office until this investigation," Michael Cherkasky told me.

The tension between the Manhattan D.A. and the Justice Department would reach its peak in confrontations between Robert Morgenthau and Robert Mueller, the head of the Criminal Division in Washington. As a general matter, the Justice Department resists efforts by local prosecutors or congressional committees to interfere with its investigative efforts. Richard Thornburgh, then attorney general, had been ignoring the crusade of Senator Kerry since the early days of the Manuel Noriega case. "Our experience has been one of almost pathological resistance whether we have been trying to help them or whether we have been trying to get information," Kerry's counsel, Jonathan Winer, told me. "In some cases they actually prevented us from deposing B.C.C.I. witnesses on the absurd theory that it would interfere with their Noriega case."

"We have been cooperative with Senator Kerry's staff to the extent that it wouldn't damage ongoing criminal proceedings," Robert Mueller told me. What really happened at the Justice Department? Observers feel that Mueller was in a difficult position. He only took over the case in July 1991 and appeared to be unable to quickly reverse the judgments that Thornburgh had made regarding the handling of the B.C.C.I. case. "We would walk into the boss's office," Cherkasky remembers, "and we would hear him say on the telephone to Bob Mueller, 'Bob, if you want to play that game, we will play that game. You behave that way and we will behave that way. It is going to be two ways! You think you can get away with this. You can't. And we don't need you.' "

In July 1991, after B.C.C.I. was shut down worldwide, Clark Clifford finally arrived at the offices of the Manhattan D.A. to be interviewed by the prosecutors. There was a palpable excitement when Clifford, an icon of the Democratic Party, appeared on Centre Street. He walked slowly and carried his trademark fedora. He answered many questions with historical digressions, a style which had been effective in the past. It was a strain for the young prosecutors to listen to the stories-within-stories.

"I asked him if he had ever asked Adham if he was ever involved in Saudi intelligence," Moscow told me, "and he said, 'No.' I asked him, 'Why not?' and he said it was none of his business. I have to tell you that offended me."

Morgenthau stayed out of the room when Clifford was being interviewed. "I thought we would have to physically restrain the boss," Mike Cherkasky told me. "He was dying to come in, but he knew he could be called as a potential witness if he was a party to Clifford's interview."

In his interviews in New York, Altman was more emotional than Clifford. At times, he was near tears and mentioned his anxiety over the investigation and his finances, now that the law firm had broken up. "I kind of feel sorry for the guy," one prosecutor told me.

December 1991: It was a few days before Christmas and the press conference in Morgenthau's office to announce the B.C.C.I. plea was packed with reporters. Bob Morgenthau had been anticipating this moment for months, and his staff had worked the phones to get the word out. Morgenthau's blue leather chairs, which were usually around his conference table, were arranged in even rows. As always, a particularly handsome picture of John Kennedy was placed at a certain angle on a bookcase behind where Morgenthau was seated so it would appear on the nightly news. The reporters filed in early and listened patiently as Morgenthau read through the entire press release of the B.C.C.I. plea. It was an extraordinary triumph because the Manhattan D.A. shared the plea with the Justice Department. Morgenthau's campaign to turn the Justice Department around had finally worked. With Thornburgh gone, Justice now has about fifty-five full-time staff members and seven grand juries assigned to the case.

"Finally, they have realized the enormity of this case!" Morgenthau had told me a few days earlier. He was, he said, "getting tremendous cooperation" from William Barr, Thornburgh's successor. Now when Mike Cherkasky went to see Bob Mueller, he was ushered into a room that had special electronic maps and red telephones that seemed to connect to every point in the world. "It's sci-fi down there," Cherkasky told me, "a study in contrasts from our dump. What a difference in their attitude! Now I get driven to the airport."

At his press conference, Morgenthau was lavish in his praise for the new Justice Department. "Are you prepared to say that the U.S. Justice Department afforded you 'unprecedented cooperation' early and responded early to the allegations brought to its attention?" one reporter asked. Morgenthau was all ready for the question. "I have a very short memory span—it may be a sign of my age," he said. The room erupted with laughter, for Morgenthau's conflicts had become common knowledge. "We have had excellent cooperation in the last month," he added.

"Mr. Morgenthau, have you taken at face value the assertions of Clark Clifford and Mr. Altman that they were duped in this matter?" another reporter asked.

"No," he said firmly. "This [plea] doesn't wrap it up at all."

A few weeks later, I returned to criminal court. Morgenthau had had a possible major piece of luck. The former head of the Washington B.C.C.I. office, Sani Ahmad, had been arrested when he returned to the United States for seventytwo hours to try to sell his house in Bethesda. Ahmad had fled to Pakistan a year earlier after receiving a phone call from John Moscow to come to New York for an interview. Morgenthau had gotten a tip from the Fed that Ahmad had slipped back into the country, and passed it on to the F.B.I. He was a potential bombshell witness for the Manhattan D.A. because, as Moscow phrased it, "he might be able to explain how $23 million flowed through the Washington office of B.C.C.I." Investigators suspect much of that money was used to bribe U.S. government officials and Ahmad presumably could reveal their names. Another item of interest is a memo in which, according to prosecutors, Ahmad is referring to Manuel Noriega: "It may be worth mentioning that we have placed over $13 million in different U.K. branches [of B.C.C.I.] for a single customer from Panama."

Ahmad's hearing was scheduled for Part 70, a large courtroom filled with drug cases and legal-aid lawyers. "Stop snappin' that gum!" the clerk yelled into the courtroom as two impeccably dressed lawyers arrived, clearly representing the B.C.C.I. man. Ahmad never appeared, and the judge, at the insistence of his lawyers, closed the proceedings.

The lawyers left the courtroom for a conference. They moved quickly down the long beige corridors of criminal court, their heels clicking on the tile. "What is your name?" I asked one of them. In any other case it would have been an innocent question, but not with B.C.C.I., a swamp of questions with few answers. "We don't have to tell you anything," he said.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now