Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLIFE-STYLES OF THE RICH AND INFAMOUS

Thanks to France's open-door-to-despots policy, exiled tyrants are turning the Riviera into a new Gold Coast

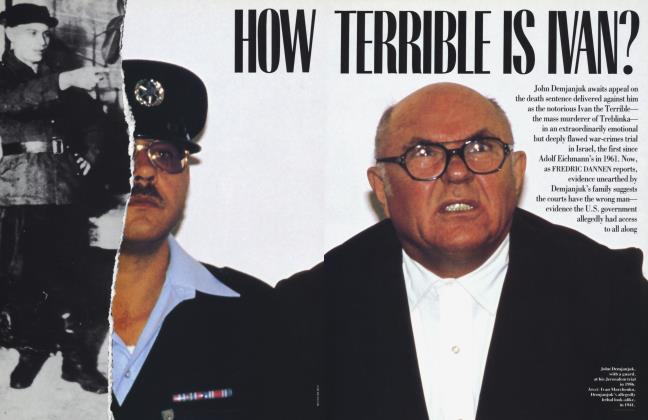

FREDRIC DANNEN

Dispatches

It is not my business to judge anyone," says the hcadwaitcr at the Moulin de Mougins, a three-star restaurant on the French Riviera. He is straining for a comment about a former patron, JeanClaude "Baby Doc" Duvalier, ex-dictator of Haiti, who has lived in the South of France since his overthrow in February 1986. "What can I tell you? He's quite charming. I'm sure he could have your head cut off most agreeably. It is all in the presentation." When the restaurant's owner Roger Verge stops by the table, he smiles at the mention of Duvalier's name. Baby Doc was so fond of Verge's cuisine that he had it delivered, paying the $2,000-aday food bills in cash. But then Duvalier split with Haiti's former First Lady, Michele Bennett Duvalier, and moved to another home farther down the Cannes autoroute. On a more positive note. President Mobutu Sese Scko of Zaire, desperately clinging to power, may soon become the next dictator to take refuge on the Riviera. "Mobutu has a house in Cap Martin," Verge points out, adding for good measure, "We are apolitical."

France has long played host to all manner of fallen potentates while the rest of the world turned up its collective nose. Even Omar Bongo, the president of Gabon, had refused Duvalier, reportedly declaring, "Gabon nest pas une poubelle"—Gabon is not a garbage can. French officials arc perhaps especially ticklish about royal asylum right now because of the giddy prospect of having another notorious exile in the South of France, turning the long coast road into a Boulevard of Broken Dictators. The new name added last August to the list of houscgucsts under asile regalien (literally "royal asylum") was that of General Michel Aoun, commander in chief of the Christian Maronite forces in Lebanon. France has traditionally supported the Maronites, and President Francois Mitterrand said that giving Aoun refuge was "a matter of honor." The Mad General, having waged a bloody and futile "War of Liberation" against Syria, and then a bloodier and even more senseless "War of Unification" against his fellow Christians, now sits in a safe house in Marseilles, where he remains under virtual house arrest, for his own protection. (His wife and three daughters live under heavy security near Paris.)

The argument made in favor of France's hospitality toward tyrants is the same one advanced by the U.S. State Department in accepting Ferdinand Marcos: if you offer a safe and comfortable haven to a dictator, it may encourage him to leave power and avert further bloodshed. Despite this splendid rationale, it is difficult to find anyone in the French government willing to discuss the subject. Even Daniel Bernard, chief spokesman for the Quai d'Orsay, France's foreign ministry, a man who usually loves to cross swords with American journalists, declined to discuss his nation's dictatorsin-residence program.

Those of a cynical turn of mind will tell you that France's motives are more pragmatic than humanitarian. For one thing, dictators-in-residence tend to be large importers of their nations' wealth. Mobutu is a case in point: he is said to have amassed a personal fortune of1 $5 billion, about the size of Zaire's national debt. The son of a hotel cook, Mobutu has been Zaire's absolute despot for nearly three decades and still insists that, despite the civil and military unrest that has torn apart his nation of nearly 40 million, he has no plans to step down. But last fall his private plane carried one of his two wives and other family members to the Villa del Mare, his fourstory pink-and-white marble palace in Cap Martin. Mobutu once used the spectacular home—on twenty-five acres, complete with helipad—to host an unsuccessful peace conference on behalf of Angola. He also reportedly owns the Chateau Fond'roy, near Brussels, mansions in Paris and Switzerland, a castle in Spain, and a ranch in Portugal.

Several of Mobutu's allies, including France, have recently cut off financial aid in order to pressure him to accept democratic reforms. Yet there is no reason to believe that France would forbid Mobutu to settle in Cap Martin or Paris, or question him too closely about the origins of the wealth he would bring.

Nor was any real scrutiny applied to Baby Doc, whose arrival in France five weeks before a key election was an embarrassment to the Socialist government. The one notable disappointment from a consumerist standpoint has been Emperor Jean-Bedel Bokassa of the Central African Republic, the only head of state in recent memory to be tried for cannibalism.

In 1983, Bokassa took refuge in a chateau in Hardricourt, just west of Paris. While in power, Bokassa had had enormous wealth at his disposal; he had even given diamonds to former president Valery Giscard d'Estaing, the scandalous disclosure of which helped doom Giscard's re-election campaign in 1981. But in France, Bokassa was busted out. His water, telephone, and electricity were often shut off for nonpayment, and he refused to post bail for his three children when they were caught shoplifting. Either because he was bored or broke, he returned home to Bangui in 1986 and was sentenced to death, a sentence ultimately commuted to life in solitary confinement.

Of course, the presence of the Duvaliers is still a delicate subject, especially now that France is aggressively supporting one of the former despot's greatest foes, Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The revolutionary Roman Catholic priest, who took office in February 1991 as Haiti's first truly democratically elected president and was forced into exile by a military junta seven months later, has no stauncher ally than France. The French government even granted its ambassador a medal of honor for protecting Aristide's life during the coup. He has also become the pet cause of First Lady Danielle Mitterrand.

Whether Aristide will return to power remains an open question; Duvalier should know his own return is beyond the realm of possibility. The dull-witted fat boy with boot-shaped sideburns, who, just shy of nineteen, was thrust into office upon the sudden death of his sadistic father, Francois "Papa Doc'' Duvalier, lasted fifteen years as "President for Life." His downfall was all but guaranteed in 1980 when he married a coarse-mouthed mulatte, Michele Bennett, and then allowed her to loot the national treasury. The end came on February 7, 1986, amid rioting. When the Duvaliers disembarked in Grenoble, Prime Minister Laurent Fabius declared that Baby Doc would be permitted to remain on French soil for eight days at most. That was six years ago.

France has long played host to all manner of fallen potentates while the rest of the world turned up its collective nose.

Those years in exile have not been kind to Duvalier. The tubby ex-dictator has moved through a series of homes, each less luxurious than the last. He appears to be paying for his female companionship these days, having filed for divorce from his wife after she humiliated him with a highly public love affair. She, meanwhile, is contesting the divorce—she wants more money—and now lives in Paris with a rich Lebanese arms merchant and her son and daughter by Baby Doc. Every fortnight he goes up to Paris to spend a weekend with his children and to see a medical specialist—he is diabetic and, according to his lawyer, also has a thyroid condition. Duvalier will be forty this year. He seems a prime candidate for a mid-life crisis.

It is even possible, though not terribly likely, that Duvalier is running out of money. He is known to have diverted at least $120 million from the Haitian treasury into his own foreign bank accounts, and is suspected of having taken more, though how much more is anyone's guess. Today, he has at least one foreign bank account with a large chunk of liquid capital. Samir Mourra, a Haitian of Syrian extraction who is distantly related to the family of Michele Duvalier, functions as Baby Doc's courier. Every six weeks, Mourra disappears for a day and returns with a valise full of cash in the trunk of his car—an estimated $100,000 per trip.

Baby Doc now lives in Villa Melica, a two-story stonework house in Vallauris, a small, quiet burg near Cannes. He shares his home with Mourra, a few minables—poor friends and relatives from Haiti—and domestics. One neighbor who has seen the inside of the villa describes it as modest in size, a bit vulgar in decor. Baby Doc rents it furnished from Theodore De Mel, the Ivory Coast's former ambassador to London. It is said that, after an unsightly crack appeared in the living-room wall, Duvalier stopped paying his rent.

Last summer Baby Doc threw himself a birthday celebration at a hotel on the Cap d'Antibes, but apart from that, he appears to do no entertaining. His days seem to consist of sleeping late, having a long lunch at one of the restaurants on the Croisette—a touristy promenade in Cannes—and then returning to the same beachfront for the nightlife. Neighbors often see him driving his BMW, always alone, a blank expression on his face. Now and then, a taxi pulls up to the villa and deposits a young Nigoise with long blond hair ("a tart," one neighbor sniffs). Three nights a week on average, Duvalier ends up at La Chunga, a tacky Latin-style piano bar across from the Martinez hotel, where, on a recent evening, a bad Tom Jones imitator played an electronic keyboard and sang American pop standards such as "Mrs. Robinson" with an impenetrable French accent. Dressed in a business suit, Duvalier sits listening, looking grim and determined, until the early hours of the morning.

From his drawing room at the Villa Gaby, high atop a seawall on the Corniche Kennedy in Marseilles, General Aoun has a panoramic view of the ocean, and of the cadre of riot troops and municipal police armed with carbines and semi-automatics who patrol out in front. Metal barriers obstruct a long stretch of sidewalk beneath the dignified manse of yellow and white stucco, forcing pedestrians to walk along the ocean, where they must pass through a gauntlet of security men. The seafront has the air of an armed camp.

While the United States charged the Shah of Iran for his protection when he visited an American hospital, French security comes free, though the price is often enforced silence. This has proved difficult for Michel Aoun, a man whose pomposity won him the nickname "Napolaoun. "

While Baby Doc left Haiti a far richer man than Michel Aoun left Lebanon, one should not underestimate the generalissimo's resources. Two years ago, the French satirical weekly Le Canard Enchaine disclosed that he had two bank accounts at the Banque Nationale de Paris totaling more than $15 million.

The question of Aoun's financial resources will resurface if his followers in France manage to purchase him a new home.

One residence that has reportedly been considered is Lou Soubran, a mansion near Nice that used to belong to Jacques Medecin, the city's mayor. (In September 1990, Medecin, who had been mayor for almost twenty-five years and a virtual monarch on the Riviera, became France's own king in exile when customs officials found $140,000 in cash in his luggage. He took refuge in Uruguay rather than face charges of embezzlement.) When asked whether his people have indeed placed a bid on the Mcdecin house, Aoun is vague: "Yes, I heard that, too. I read it in the newspapers. But, you know, I have no money. And, anyway, if I had money it would not go toward buying houses.''

Aoun is speaking by telephone, in open defiance of the gag order placed on him by the French government. A few days later, he suddenly does broach the possibility of becoming a homeowner in France. "We are looking at a house in Orleans. You know Orleans? It is where Joan of Arc became famous. She was a legend. I too am a legend. Now Orleans will have two legends. Isn't that right?"

Dictators-in-residence tend to be large importers of their nations' wealth. Mobutu is said to have amassed a personal fortune of $5 billion.

It is an uncommon flash of humor for the fifty-six-year-old Aoun—-that is, if he's joking. His confinement at the Villa Gaby has clearly demoralized him. Aoun's distinctive voice, with its menacing lilt, has lost its energy. He is a general without a battleground, reduced to puttering around the large house in his civvies. Unlike the other Christian militiamen, who wore T-shirts over their fatigues, Aoun's men always dressed, like their boss, in the full Lcbanese-army uniform. Aoun's thick fatigues also helped hold in his waist—the tough, compact figure had started to spread in middle age. A recent visitor found him wearing loafers and an old cardigan, with bags under his eyes, looking as drawn and exhausted as a man with a heart condition.

Aoun had wanted a face-to-face interview; it sounded as though he would have been glad for company. Reached from a pay phone a block from the Villa Gaby, he immediately made an appointment for the following morning. But the next morning came, and it proved impossible to get through to the general on his private phone line. His link to the outside world was out of order. Another number at the villa was answered by a French official. There will be no interview, he said. No reason was given.

It was a cruel twist for Aoun to have someone else barring his doors against visitors. For two years, he had barricaded himself inside the presidential palace at Baabda, just outside Beirut. A butcher's son who rose rapidly through the military, Aoun had become Lebanon's acting head of state by default in September 1988, when President Amin Gemayel failed to win a plurality. Gemayel is said to have anointed Aoun fifteen minutes before heading for the airport to spend his retirement—and some of his estimated billion dollars in embezzled funds—in, of all places, Paris. About a year later, fifty-eight constitutionally elected Christian M.P.'s gathered at a disused air base in Lebanon to vote for a new president, despite a warning from Aoun that those who did so might place their lives in danger. They chose Rene Moawad, a man instantly denounced by Aoun as a pro-Syrian stooge. On the dusty grounds outside the palace, Aoun's guards tethered an old donkey and painted on its flank the words l LOVE MOAWAD in Arabic. Moawad was too frightened to venture back into Christian East Beirut. He took refuge outside the city for a few weeks, then embarked for mostly Muslim West Beirut for inauguration ceremonies. On his way there, his car was blown up by a bomb; he died instantly.

Moawad's death left Syrian-backed Elias Hrawi in charge. But Aoun faced another challenge, too—from his fellow Christians, the 10,000-strong Phalangist militia. By early 1990, Syrian forces were able to settle back and enjoy the spectacle of two Christian factions killing each other. In October, Aoun finally capitulated to Hrawi and was spirited to the French Embassy—apparently, as Robert Fisk of The Independent put it, "preferring coffee with the French ambassador to falling on his sword." He remained there for ten months before the Lebanese government granted him a "special pardon" and a forty-eight-hour safe-conduct pass. A convoy drove him to a naval base in northern Beirut, where he was put on an inflatable speedboat and taken to a submarine two miles offshore, bound for Cyprus.

No sooner had Aoun arrived in Marseilles than French foreign minister Roland Dumas appeared on television to express his "pleasure" at the general's arrival, once again baffling the rest of the world over the vagaries of French foreign policy. France had officially backed President Hrawi, though Aoun remained enormously popular with the French people, who seemed to share the belief of the general's die-hard Maronite loyalists that his goal was to unite all of Lebanon into one Christian-led democracy. At a press conference a few days after Aoun's arrival, President Mitterrand acknowledged that the general's policies had sadly pitted Christian against Christian and strengthened the grip of foreign armies on Lebanese soil. He offered no insight into France's eagerness to welcome him.

Now, after more than a year in French custody, Aoun is bored. In what will become an almost daily discourse on the phone, Aoun requests books: the first two volumes of William Manchester's biography of Winston Churchill, and The Samson Option, Seymour Hersh's recent expose of Israel's nuclear capability. "That Hersh, he has really made a noise there," Aoun says. The general is struggling to keep up with current events—he inquires about the Middle East peace talks and rumors that Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Shamir will step down and spark an early general election. This seems a good idea to Aoun. "Elections are very important. The people must decide. That is what the biblical notion of the shepherd is all about. A shepherd cannot abandon his flock, so a leader must not turn his back on his people." Apparently, political asylum has dulled the general's sense of irony.

Above all, Aoun sounds annoyed with the French, who have saved him from almost certain assassination. One afternoon, before considering his move to Orleans, he is struck by another thought entirely. "What is the weather in London? Is it cold, raining? Will they take me in England? Ask them for me, will you? Please. But maybe I should wait until the weather is warmer.

"If I have done wrong," Aoun says, "then let the world know about it. Let me be put before a jury. But you can't condemn me to silence like this. You cannot hold a man like this. 1 want to get out. I want to get out of here."

Eighty-five miles east of Aoun's fortress home, Pierre Donnet, the mayor of Vallauris, is reclining in a black Eames chair behind his semicircular desk at the town hall. He seems a bit taken aback by the subject at hand.

"Jean-Claude Duvalier? I was never officially informed of his presence in my town. For me, his existence is anonymous. I have never met him. . . . No one has discussed him with me, eh? Not the prefecture, not the police, not the Renseignements Generaux [French federal police]. . .This is a decision that comes from the state, from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Since I was never informed officially of anything, I don't even know if his residence is surveilled in my town. Evidently, it's a surveilled residence, and he has accounts to render to the police. I don't know."

Every six weeks, Baby Doc's courier disappears for a day and returns with a valise full of cashan estimated $100,000 per trip.

Still, Donnet is being a good sport about it, or perhaps he really doesn't care all that much. By contrast, in March 1986, when Duvalier arrived with his entourage at their first home, a ten-room villa in Grasse, the local mayor, Herve de Fontmichel, was in an uproar. No one had informed him either, and in a statement published in the Riviera's leading newspaper, Nice-Matin, he declared that "the population, the municipal council, and I are outraged at this show of force, born of the alliance between the current Socialist government and Mr. Duvalier. . . . My position is quite clear: I reprove this decision." So did a number of locals, who picketed and scribbled anti-Duvalier graffiti on walls.

Duvalier apparently has never felt the need to defend himself, and he long ago stopped giving interviews. One of his last, which appeared in Paris Match in February 1988, contained few surprises, apart from his unexpected fondness for the nickname Baby Doc. He blamed his downfall on a host of unfair and exogenous variables, from a hostile American press and State Department ("Foreign affairs is not the forte of American politics") to racism and the effect of the AIDS scare on tourism ("We are the four bad h's: homosexuals, heroin junkies, hemophiliacs, and Haitians"). He could find no fault with himself or his wife. "Michele is very beautiful and thus very much envied. The people loved her. It was necessary to attack her to bring me down."

Not that he had ever sought or been groomed for the presidency. "The son of a bitch never told me anything," Baby Doc once said of his father, according to Elizabeth Abbott's richly detailed history, Haiti: The Duvaliers and Their Legacy. JeanClaude, the only boy of four children, was five years old when Papa Doc took power in 1957 in a rigged election and moved his family into the National Palace in Port-au-Prince. Nicknamed "Fat Potato" and "Baskethead," the young Duvalier vied to be last in his class, until, legend has it, he forced the teachers to stop posting his grades. Francois Duvalier had little time for his son, apart from occasionally storming into his room to unplug the record player.

Papa Doc was not only a man of brutality—he ordered schoolchildren to witness political executions and liked to commune with the severed heads of his enemies—but a thief on a spectacular scale. He had risen to power on a campaign of noirisme—Haiti's black majority had long been oppressed by the nation's mulattoes—then sold black Haitians into virtual slavery, for $1 million a year, to work on the sugar plantations of light-skinned Dominicans.

The oldest child, Marie-Denise— "Sister Doc"—was far more intelligent and ambitious than her brother, and the odds-on favorite to succeed their father. But in 1971, Duvalier, now terminally ill, was warned by his advisers that Haitians would not tolerate a young woman as president. Posters soon appeared on walls and billboards everywhere, showing a frail Papa Doc resting a hand on his son's beefy shoulder, with the caption: "I have chosen him." Francois Duvalier died on April 21, a week after his sixty-fourth birthday. Baby Doc was so distraught—more likely from the shock of finding himself the new President a Vie than from grief—that he took an overdose of Valium and missed the funeral.

The young president appeared to devote more time to his favorite hobbies— racing cars and motorcycles, hunting, and sleeping with every available female—than to governing his country. The Tontons Macoute, his father's ruthless civil militia, still terrorized the populace, and Baby Doc left most decisions to his mother, Simone "Mama Doc" Duvalier—that is, until another woman came along to shove her aside. Michele Bennett first encountered the president-to-be as a twelve-year-old classmate at College Bird, near the palace. In 1963 a failed assassination attempt on Baby Doc and his sister Simone, which claimed the lives of their three bodyguards and chauffeur, occurred in front of the school. Alarmed, Michele's father spirited her off to St. Mary's Convent in Peekskill, New York. She later moved to Manhattan, working for a family that manufactured slippers for big-footed women. Michele returned to Haiti in the late seventies as a divorcee with two sons and a reputation for her sexual prowess. After she and Baby Doc were paired up at the Duvalier ranch, he supposedly announced that he had finally met his match. Their wedding in 1980 made the Guinness Book of World Records as one of the costliest ever.

The First Lady's indulgences became legendary. Preferring Miami's flowers to her nation's own, she had them flown in at a cost of $50,000 a month. A refrigeration unit was installed in the palace to preserve her growing supply of fur coats, acquired on million-dollar shopping sprees in New York and Paris, and her collection of jewels required a mobile vault. "She didn't think of her country as anything except a cookie jar," says an investigator who worked for post-Duvalier Haiti.

The United States turned on the dictator in early 1986, with White House spokesman Larry Speakes mistakenly announcing that Duvalier had left Haiti. Panicking, Jean-Claude got on the airwaves to announce that he was still "strong as a monkey's tail," but a week later the Duvalier clan threw a final champagne party, then drove to the airport, where a U.S. Air Force C-141 was waiting to carry them to France.

When the plane touched down in Grenoble, the local prefet, a mere civil servant, was the highest-ranking French official there to greet Duvalier. A week later, on February 14, he was hit with an order of expulsion, signed by Interior Minister Pierre Joxe. Meanwhile, Foreign Minister Roland Dumas wrote a letter to U.S. secretary of state George Shultz that said, in effect: You take him. But apart from providing the plane to remove him from Port-au-Prince, the United States, which had its hands full with the Marcos problem, wanted nothing to do with Baby Doc. Negotiations to get Liberia to accept Duvalier fell through. In any case, according to Philippe Madelin, a reporter for Television Frangaise at work on a book about the stolen wealth of former dictators, France's efforts to expel Duvalier were "a ruse for the sake of public opinion. In reality, the French government had decided to give him royal asylum. It was a decision of state."

"We are looking at a house in Orleans " says Aoun. "It is where Joan of Arc became famous. She was a legend. Now Orleans will have two legends."

Evidently, a deal had been negotiated by Baby Doc's high-powered French lawyer, Sauveur Vaisse. Once a radical who defended Algerian rebels against the government of de Gaulle, Vaisse was recruited by Papa Doc in the late sixties to serve a cause rather less heroic: he persuaded the French courts to ban the film version of Graham Greene's The Comedians, a scathing portrait of Papa Doc's Haiti. Now in his late fifties, with a grizzled beard that makes him look like a Marseilles fisherman, Vaisse speaks eloquently of his attachment to the Duvalier cause. A typical pronouncement: "I became persuaded that a lot of the criticism of the regime of Frangois Duvalier was racist."

Vaisse is less helpful in explaining the peculiar nature of Baby Doc's status in France. Duvalier has no official papers or identity card, and one presumes that his Haitian diplomatic passport is no longer valid. For all practical purposes, he is a nonperson. The only documents issued him by the French government have been Joxe's expulsion order and a contradictory order issued three days later, called an assignation a residence. This is a writ that requires a person to live within a specific area—Duvalier was condemned to the Alpes-Maritimes, which includes the choicest section of the French Riviera.

It was just as well that Baby Doc and his dozen relatives and domestics had to leave Talloires, their first stop after Grenoble. Accommodations at the four-star Hotel de l'Abbaye came to more than $12,000 a day. (Michele paid with her Diners Club, American Express, and Visa Carte Bleue.) The Duvalier clan relocated to La Tourilliere, a five-acre property with a swimming pool and tennis court, in Grasse. Baby Doc rented the house from Dutch businessman Hubertus Nijssen for about $7,000 a month. Perhaps because of the protests and anti-Duvalier graffiti, Baby Doc did not renew his lease, but instead moved on again, to Mohamedia, a villa in Mougins that belonged to Mohamed Khashoggi, son of arms merchant Adnan Khashoggi. Now his rent was down to $6,500 a month, but the villa was next to a lettuce farm and had small rooms.

In this cramped environment, the stage was set for marital strife. As it was, Baby Doc was having adjustment problems. Only twice in his life had he ventured outside Haiti, both times for brief visits to France. In a 1986 interview with Vanity Fair, Michele mocked her husband's difficulty in distinguishing the sidewalk from the road and in performing such mentally taxing chores as telephoning for reservations at the Moulin de Mougins. Duvalier, who is terrified of snakes, found one swimming across his pool and would not use it again. The couple's children—three-year-old Nicolas and oneyear-old Anya—were terrorizing the house. ("Anya, she's a hurricane," Michele said at the time. "The other day she ate three lipsticks.")

The only relief from the boredom and tension, it seemed, was sex, in which both Jean-Claude and Michele maintained a healthy interest, though not with each other. Jean-Claude was said to be discreet about his love affairs, keeping a bachelor's apartment in Cannes to entertain Haitian girlfriends he had flown in from Port-au-Prince and Miami. Michele was less discreet. "She cheated on him in the most shocking way," says a Paris-based source who has known the couple for years. "She had a little boyfriend when she was eighteen years old. Now he's forty, and working at some job at a bank in Haiti. She paid his plane fare to Nice and spent a couple of days with him, this guy she hadn't seen for more than twenty years. And told JeanClaude about it. It's rough, eh?"

All the same, Duvalier appeared to want to preserve his marriage, until another exiled Haitian began badgering him to get a divorce. Dr. Roger Lafontant, the former head of the Tontons Macoute, had long hated Michele, first merely for being a mulatto and then for forcing him to marry his mistress in preparation for Pope John Paul II's 1983 visit to Haiti—he could not shake the hand of His Holiness, she insisted, if he was living in sin. Lafontant argued that Michele's unpopularity had cost Baby Doc the presidency, and that it could be his again if he would leave her. "Jean-Claude let himself be swayed by Lafontant, though the divorce was not really his wish," says a man who served under Duvalier. "He loved his wife. I believe he still loves her."

Lafontant tapped the ex-dictator for $400,000, more than enough to buy a divorce in the Dominican Republic without having to set foot there. (The actual cost of the bogus divorce decree, in fact, was a mere $14,000.) Michele seemed perfectly willing to split with her husband of nine years, and promptly re-

sumed using her maiden name. However, she was less than thrilled with the alimony set by the Dominican court: about $7,500 a month. She is now challenging the divorce in France on the grounds that her husband's documents are forgeries.

As for Lafontant, though he made a handsome profit as a divorce broker, the money was soon spent, and Baby Doc refused to give him any more. Short of funds, Lafontant defied an arrest warrant for treason and returned to Haiti. In January 1991, a few weeks after the election of Father Aristide, he briefly seized power in a bloodless coup-—"I am the president now and we are very busy forming a new government," he told The New York Times—then was thrown in jail and later executed.

As for Baby Doc, his notoriety has largely faded. Cannes natives have become so indifferent to his presence that when they refer to him at all it is often as "Papa Doc." Apart from a television camera at the front gate, there are no security measures in evidence at the Villa Melica—a dramatic contrast to the villa in Mougins, where a shotgunwielding security man crouched behind a cypress tree, and Grasse, where the grounds were teeming with geese, guaranteed to launch into honking conniptions at the first sign of a trespasser. The only animal you are likely to encounter at the Melica is the caretaker's ancient, drooly-mouthed Doberman or one of Baby Doc's Chihuahuas.

The caretaker, a stocky former police commissaire with an iron-gray crew cut, is employed by the landlord, Ambassador De Mel, not by Duvalier, whom he apparently loathes. "When the caretaker talks about Baby, he's always bitching," says a neighbor. "He says Baby is rude, arrogant, and talks down to him like a servant. And he won't pay for things. The caretaker has a real problem trying to get the upkeep money out of him."

'My husband-—I call him my husband because we are still not divorced— they say he was a dictator. But they know that is not true. Aristide was the dictator."

Six years of exile have done nothing to take the ginger out of Michele Bennett. As she talks by phone from her Paris apartment, there is plenty of exuberance in her husky voice. And, as ever, a need to talk, even at the expense of her French hosts.

"France hasn't been doing well with foreign affairs," she says. "And now the French are supporting Aristide. Mme. Mitterrand is pushing for that. . .priest. I'm more angry at the position of France than the United States. I know the United States didn't like Aristide, but as he was elected democratically, they had to say something positive. Although, you know, Haitians don't go to the polls. How can you have a democracy when you have so many illiterate people?"

Bennett puts her caller on hold and a set of chimes merrily plays "Greensleeves." Moments later, she is back and on a tear: "Sure, Aristide was popular. He's from the slums, like the people. . . . Politics, I was in it by accident. I have no political ambition for myself, and never did—unlike a lot of women. I don't criticize."

With that, she signs off by reminding her caller that she no longer gives interviews.

It seems appropriate to pay an unsolicited call on Madame La Presidente. Her regal eagle nest is in the Sixteenth Arrondissement, on the Right Bank of the Seine, in one of those majestic old buildings with a foyer large enough for touch football. Monsieur Robert, a black manservant, opens the door to her apartment. Down the long red-carpeted corridor, one can observe with awe the Versailles-like touches—crystal chandeliers, a dramatic marble staircase, and floor-to-ceiling oil paintings that are either old Flemish masterworks or suitable replicas.

"What a surprise," Michele Bennett says as her visitor is escorted in. She sits at an antique secretaire, doing her day's work, which consists of answering mail and making notes for her memoirs. A Pavarotti CD is playing on the stereo. There is no sign of her Lebanese armsmerchant consort, whose existence in her life she does not acknowledge— even one of her friends knows him only by his first name, Alexandre. No less ravishing than usual, and dripping with gold and precious stones, Bennett apologizes for not being "made up" to receive a visitor. She wears a knit chemise featuring the title characters from One Hundred and One Dalmatians, and it is hard to suppress the thought that with her cigarettes and love of furs she could have been a model for Cruella De Vil. Bennett chain-smokes Dunhills. "I need to quit. I'm losing my voice. I always had a hard voice, not really sweet like some women, but it's becoming worse because of cigarettes. The doctor told me I have very fragile vocal cords."

She must keep the conversation brief, she says, because it is almost time to take Anya to her ballet lesson. Baby Doc's daughter and son are now six and eight, and have calmed down a bit. The subject of her two other sons, in school in Miami, causes some distress. "I am not as yet able to leave the country," she says. "And the only thing that might bother me is that if my boys in the States need me I cannot go. So I touch wood they don't get sick.

"But," she continues, "I'm not a person who complains. We never had any problems in France. After Haiti, France is our second home. I'm leading a normal life. I have lots of friends that are French. Paris is beautiful and we are lucky to be here. Of course, I do miss Haiti. You know, there is nothing better than home. ' ' Asked whether she misses her husband, Bennett smiles coquettishly. "Divorce is very sad for the children," she says at last. "But sometimes it happens. "

Michele Bennett has good reason to keep quiet about her divorce. The dispute over her settlement has put her and Jean-Claude Duvalier in a delicate position. She wants half of her husband's assets, and if she names a specific figure, it will finally become known just how much he stole. Estimates have ranged as high as $800 million, which, at three times Haiti's annual budget, may be a bit unrealistic. But there is no question that $120 million was his minimum haul—he left a paper trail of checks totaling this sum, drawn on government accounts at commercial banks in Haiti. What no one knows is how much money went out in suitcases.

Sauveur Vaisse, however, refuses to think of his client as a thief. "The accusation has absolutely not been demonstrated," he says. "Not at all. .. . We have records to show that a lot of the funds they accuse Jean-Claude Duvalier of keeping for himself were in fact used for the public good."

Accommodations at the Duvaliers' first stop in France, the four-star Hotel de I'Abbaye in Talloires, came to more than $12,000 a day.

Haiti has recovered only a fraction of Baby Doc's wealth, and largely has itself to blame. Each new government over the past six years has sworn to crack down on Duvalier, then limited the effectiveness of the law firms and private investigators in charge of the effort by not providing crucial documents and witnesses—and not paying its bills. Apparently, every administration until Aristide's had its own secrets to conceal. France's cooperation in the case against Duvalier has also been ambiguous, suggesting the lack of a definitive policy on the ex-dictator. At one point, the French government dropped hints that it would consider a motion by Haiti to change Baby Doc's assignation a residence and force him to move to some grubby northern mining town or even French Guiana. But Haiti never made the request.

Instead, Duvalier has merely had to endure some harassment. His worst day was February 11, 1988. At six that morning, by order of the tribunal of Grasse, fifteen French officials descended without warning on his villa in Mougins with a search warrant. They came looking for financial documents, to be turned over to the Haitian government. The Duvaliers were rousted from their beds, and Michele had no time to dispose of her pink-and-purple suede notebook, in which she kept a record of the presidential couple's expenditures. The notebook confirmed that the Duvaliers paid virtually all their bills in cash, including $10,475 for their phone bill in December 1987. The same month, Michele spent $455,000 at Boucheron, her favorite Paris jeweler—$13,000 went toward a cigarette lighter. Some of the smaller sums were cash disbursements to "Tonton," her curious nickname for her husband. There was also a clue to Sauveur Vaisse's continued loyalty to the cause of Duvalierism: legal fees totaling $425,000, paid to him in cold cash.

Vaisse's principal legal nemesis in Haiti's case against Duvalier wasn't in it for the money, which was just as well. Haitian-born Jacques Sales is a mergers-and-acquisitions specialist with a French doctorate in law and a postdoc degree from Harvard. The night Duvalier was overthrown, Sales went out to celebrate. ''I got kind of drunk," he says, "and I decided that I would participate in the effort to recuperate the money that had been stolen. I thought I owed something to my country."

Friends of Sales's believed there was another, darker reason for his taking the case. Around 1970 his sister Gilberte became one of Baby Doc's favorite mistresses. Eventually they broke off their relationship and she left Haiti. For years afterward they didn't see each other, but she returned in the spring of 1985 with her fiance, Dr. Raymond Bemadin. About a week before the wedding, she and Bemadin were attacked in their car, apparently by the Tontons Macoute, and burned with sulfuric acid. Gilberte Sales was airlifted to Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami with horrible bums on her face, neck, breasts, and stomach. She lingered for two weeks before dying; Bemadin lived and today practices medicine in Haiti. An article on the incident in Ha'iti-Observateur, an influential newspaper published from New York, asked "whom such a crime would benefit," and suggested an answer: "It has been confirmed that Michele Bennett had 'good reason to believe' that all was not really over between her husband and Gilberte Sales."

Jacques Sales seems to have no doubt that the order to kill his sister emanated from the National Palace. But he fervently denies that her death is what motivated him to go up against the Duvaliers. "When I first learned she had a liaison with Jean-Claude Duvalier, Gilberte became foreign to me—she was no longer my sister," he says, his eyes as hard as enamel. "Dear friends of mine had been killed by Papa Doc, and I could not understand how somebody from my family could have a relationship with the son of a monster. So the fact that my sister was killed by Duvalier thugs did not influence my decision to take the case."

The government of Haiti retained the New York firm of Stroock & Stroock & Lavan, other attorneys in England and Switzerland, and the international private-eye firm Kroll Associates. The legal strategy never varied—Duvalier should be tried in France, not in absentia in Haiti, where a verdict against him might be perceived as prejudiced. First, the lawyers for Haiti applied to the tribunal of Grasse, but in June 1987 the judge ruled that the French court was not competent to try a former head of state. Undaunted, the lawyers turned to the court of appeals in Aixen-Provence, which in April 1988 reversed the decision and agreed to hear the case on its merits. Coming on the heels of the morning police raid that had yielded Michele's notebook, the ruling looked ominous for Baby Doc. This time Sauveur Vaisse filed an appeal, to the Cour de Cassation—the highest appeals court—in Paris.

Unfortunately, none of the lawyers for Haiti had been paid even their expenses, and only Jacques Sales would continue to work at full speed under those conditions. "The lawyers hated to give up, but they couldn't work for nothing, so it was a very reduced effort," says the head of Kroll Associates' office in France, an asset specialist with the wonderfully improbable name of Bruce Dollar. On May 29, 1990, the Cour de Cassation reversed the Aix-en-Provence decision, ruling that France was indeed not qualified to try Baby Doc for embezzlement. "The decision was really too bad from a number of points of view," Dollar says, "including precedent for other cases. It's very good for dictators in France."

In the end, Haiti enjoyed only some modest victories against Baby Doc. The lawyers were able to freeze certain of his assets: a yacht in Miami; a modest chateau in disrepair at Themericourt, near Paris; a $2.5 million condominium in Trump Tower in New York; a $200,000 bank account Michele had at Irving Trust, also in New York. Apart from these, the only payoff was a lot of accumulated knowledge about Duvalier's financial chicanery, and enough documents to fill seventeen volumes. One finding was especially intriguing: in July 1987 three Frenchmen withdrew $35 million in bearer bonds from the Union Bank of Switzerland on behalf of Baby Doc. An examination of the three men showed them to have long criminal records, for violent crimes and drug trafficking.

But, for the most part, Duvalier didn't need to deal with disreputable people. "One of his primary advisers," says Bruce Dollar, "was a very prominent, very respected Swiss lawyer, who was also a lawyer for Chase Manhattan. His name is Jean Patry. He met personally with Jean-Claude and Michele. Someone with Baby Doc's kind of wealth can hire the best. You don't have to be smart; all you have to be is rich. You can hire smart."

"I'm not a person who complains," says Michele, Baby Doc's ex-wife. "Of course, I do miss Haiti. There is nothing better than home."

One smart thing Patry's firm did for Baby Doc was to convert $42 million into Canadian treasury bills, purchased at the Royal Bank of Canada. The transaction was carried out by Patry's law partner Alain Le Fort. Then a British solicitor introduced to Duvalier by Patry, John Stephen Matlin of the London law firm Turner & Co., was put in charge of managing the money. (According to a Matlin memo, he initially had trepidations, but Patry assured him that some of the Duvaliers' wealth was inherited. Despite this, Patry indicated that Matlin was now on his own.) Under Matlin's administration, the $42 million circulated one or more times through Switzerland, even though that country had a standing order to seize any Duvalier account. Perhaps the Swiss didn't know it was Baby Doc's money, because Matlin had been asked to open the accounts in the name of nominee front companies. By the time Kroll Associates pinpointed the $42 million, it was at Barclays Bank in London, where it also could have been seized. But Kroll got there a few days too late; Matlin had already moved it once again, to Luxembourg. Baby Doc still has the money, unless he has spent it.

If the French government is looking for Duvalier's hidden wealth, it isn't looking very hard, as Baby Doc has discovered. His courier, Samir Mourra, makes his mysterious trips for the $100,000 cash infusions; presumably, he does not make a customs declaration on his return. "The French authorities must know about Samir Mourra and the money. . .yet nothing is done about it. Why?" asks Christian Lionet, a Haiti specialist for the French newspaper Liberation. It is clear that Duvalier's royal asylum also comes with certain kingly privileges. According to Lionet, Baby Doc has been stopped several times by the police on the autoroute to Paris for driving his BMW at speeds of more than 200 kilometers per hour. "In France, that is a very serious infraction," says Lionet.

"If you did that, you could be fined two or three thousand dollars, and your license would be taken away for six months or a year. But the French authorities have closed their eyes to it." But these are matters that no one in the government seems eager to address. In fact, nothing is likely to disturb Duvalier's tranquillity, unless Aristide should return to power. Aristide has already disclosed his plans to hire France's most controversial lawyer, Jacques Verges, for a renewed assault on the ex-dictator. Verges was the attorney for Klaus Barbie, the Nazi "Butcher of Lyons," and was just retained by Marlon Brando to defend his daughter against charges of complicity in the death of her boyfriend. Verges confirms having met with Aristide before the coup, and says he is impatient to pick up the Duvalier dossier. He will pursue a new tack, seeking to have Baby Doc deported to stand trial in Haiti after all. (Incredibly, given the Barbie case, Verges says he hopes Baby Doc will be charged with crimes against humanity.) This might prove difficult, since France has no treaty of extradition with Haiti, but, at the very least, it could prove an interesting test of Duvalier's legal status in France.

Until such time, Baby Doc can continue staring at the beach in front of the Carlton hotel, and driving alone in his BMW along the Boulevard of Broken Dictators.

Fiammetta Rocco, a London-based journalist, provided research assistance for this article.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now