Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDISCO INFERNO

Postscript

In this excerpt from a new book, Hit Men, Neil Bogart blows the roof off Casablanca Records, and blows the profits up his nose

FREDRIC DANNEN

If you were cruising along Sunset Boulevard in the late seventies and saw what appeared to be an enormous Mercedes dealership, chances were good that you'd just stumbled upon the parking lot of Casablanca Records. Anyone who subscribed to the American Dream, Califomia-style, required a Mercedes convertible. Casablanca, the label of Donna Summer and Kiss and the Village People and synonymous with disco, embodied that dream.

The man who embodied Casablanca was Neil Bogart, a name which will forever conjure up the worst excesses of the disco era, that period of four or five noisy, drug-crazed years which ended for the music business in 1979 with a wave of unsold records sent back to distributors. Studio 54 in New York closed in 1980, Flamingo a year later. Bogart flogged the disco wagon up the mountain and saw it plummet down the other side, which is not to say that he sank the industry single-handedly—he was not the only impresario of disco, and he was as much a symptom of his times as a cause. But it is true that Neil Bogart nearly wiped out one of the major record labels, PolyGram, which bought half of Casablanca in 1977 and the rest three years later. Today, there is no vestige of Casablanca's headquarters on Sunset, a Moroccan-style fun house that rocked with mega-sound amplification and rolled with controlled substances. The site has been cleared to make way for an office complex. As for the hole that Casablanca left in the financial history of PolyGram Records, it can only be guessed at, but the number is in the high tens of millions of dollars.

Excerpted from Hit Men: Power Brokers and Fast Money Inside the Music Business, by Fredric Dannen, to be published next month by Times Books/Random House.

The story of Neil Bogart and Casablanca helps to explain the pop-music business of today. During the seventies, record companies began to spend more on stealing established acts from one another, and on the heavy promotion of a select handful of records, than on developing new talent. This shortsighted practice is still in evidence, though it always eventually leads to a weak roster and a sagging bottom line. (It explains why CBS Records, recently acquired by Sony, has lost the market dominance it held for more than three decades. For years, the label's president, Walter Yetnikoff, has stressed record promotion and talent poaching over the nurturing of new artists.)

Neil Bogart may have done more than any other individual to raise the status of the promotion man. He once told a reporter that he prepared his campaign for plugging a record "the way you would an army going to war," and Casablanca—named after a film starring another Bogart—was the first label staffed entirely with promoters. Its unofficial motto, "Whatever It Takes," became the industry's rallying cry. The idea took hold that selling the product was just as important as—maybe more important than—the product itself. And it appeared to work. When Casablanca conquered the charts, it did not dawn on the industry, or even PolyGram at first, that the company was losing vast sums of money. Sales were great, but the cost of selling was greater. "Whatever It Takes' ' was a recipe for profitless prosperity.

In an industry where excess is a virtue, Neil Bogart stories are told with awe. In 1974 he launched Casablanca Records in L.A. with a $45,000 party in the Century Plaza Hotel's grand ballroom, made over a la Casablanca the movie, down to a Dooley Wilson lookalike playing cocktail piano. When Bogart brought Donna Summer from Germany to New York to promote her first hit album, Love to Love You Baby, he had Hansen's of Los Angeles sculpt a life-size cake in her image. The cake was flown to New York in two first-class airline seats, met by a freezer ambulance, and taken to the Penta discotheque for Summer's performance there.

One night Bogart appeared on a latenight television talk show with Cher and presented her with a gold record for her new single, "Take Me Home." You must sell a million copies of a single for it to be certified gold, but "Take Me Home" had sold only 700,000. Rick Bleiweiss, then vice president of marketing at PolyGram, got a frantic call from Bogart's subordinates the next day. Rick, he recalls them saying, we can't make Neil a liar! At their insistence, PolyGram pressed and shipped another 300,000 copies of "Take Me Home,'' though there were no orders for them. Most of the records were returned for full credit, and PolyGram took a sizable loss. "I'm talking about excesses," Bleiweiss says now, shaking his head.

No one who set foot in Casablanca on Sunset ever forgot it. Asked to describe the ambience, Bogart's cousin and former number-two man at the company, Larry Harris, says, "Loud. Real loud. You see these, these are small speakers." He points to a set that reach his navel. "We were very loud." The sonic assault wasn't only from the steady ta-TUM, ta-ta-TUM of booming disco music; A1 DiNoble, the V.P. of pop promotion, struck an Oriental gong in his office whenever a Casablanca record was added to the playlist of a new station. "Everything was at such a fevered fucking pitch,'' says Rick Bleiweiss. "You walked into the office of Bruce Bird [the head of promotion], music was blaring, twelve phones were ringing. You never could talk in that building. You had to shout. Everything in that company was an exaggeration, a caricature."

The interior was patterned after Rick's Cafe in Casablanca. There was a life-size stuffed camel and a huge poster of Humphrey Bogart. There were ceiling fans, palm trees, thronelike chairs made of cane, Moroccan rugs and furniture. The mirrored office of Neil's wife, Joyce, had fabric draped from the middle of the ceiling to all four comers, to suggest a tent. Gold and platinum albums served as wallpaper.

In addition to the exotic decor and head-splitting noise level, there was something else about Casablanca. "People were happy," says Bruce Bird, now president of his own label, Camel Records, in L.A. "It was probably one of the happiest record companies I've ever seen."

It was not happy for Danny Davis, however. Davis was a short, pudgy former Borscht Belt comic who had been the promotion man for producer Phil Spector in the early sixties. He had won a number of awards, including Billboard's promotion man of the year, and was well qualified for a job at Casablanca in every respect but one. He did not do drugs.

"I must score Casablanca as the worst work experience of my life," he recalls. "Absolutely. First of all, in your own mind, you have to play out whether Neil Bogart was a great record man, or whether he was P. T. Bamum and Mike Todd. My evaluation is, he was P. T. Bamum and Mike Todd. The man was a sensational crapshooter. . . . But you can't do that twenty-four hours a day. At three o'clock in the afternoon, an adorable little girl would come up and take your order for the following day's drug supply. You understand what I'm telling you? It was the worst fucking experience of my life.

"On a Monday or Tuesday, I'd be looking for [a secretary], and I'd be calling her name. I'd look all over, and there she would be with a credit card in her hand, chopping, chopping the coke on the table.

"I would be on the phone with a program director, and a certain party would come in. And he would run around with a fucking golf club, squashing things off of my desk. And as I was on the phone, he would take a match and torch my desk. I would say into the phone, let's say to Jerry Rogers of [station] WSGA, Jerry, gonna have to hang up now, my desk is on fire.

"Neil had a unique way of co-opting people. It was real hard not to believe what he said."

"I would go into a meeting, and there on the desk would be maybe a gram and a half of a controlled substance. [An executive] would look at me and say, This shit isn't going to bother you, is it? And I would say no.

"So we would sit there till maybe about 7:30, 8 o'clock, when the gram and a half was gone. We've been in this meeting since five o'clock, not a fucking thing has been done. And now the substance is gone, and they would go into their desk and pull out the ludes. I've never taken a lude, so I can't tell you what it does for you, but I know it's great if you want to do an impression of Steppin Fetchit.

"Forget about it, man. It was absolutely the worst experience of my life. What happened to Casablanca was supposed to happen. It was supposed to go into the toilet."

Neil Bogart, the mastermind of all this mayhem, was a slightly chunky man of average height and boyish good looks. He spoke rapidly and got by on little sleep. Bogart's taste for the flamboyant carried over to his appearance, and for a time he let his curly brown hair blossom into an "Isro," a Jewish Afro. Bogart never suppressed the kid inside him. For a television program, he donned a black leather jacket, greased back his hair, and accompanied the doo-wop group Sha Na Na in a chorus of "Whole Lotta Shakin' Going On." When the Village People released their hit "In the Navy," Bogart showed up at a record convention dressed as an admiral, with his entire staff in sailor uniforms.

He was bom Neil Bogatz, the son of a postal worker. His mother ran a foster home in the Brooklyn projects where he grew up. He went to the High School of the Performing Arts, made famous by Fame, and left with show-business aspirations. He worked on Bermuda cruise ships and the Catskill circuit as a singer and dancer, then, in 1961, all of eighteen years old, cut a few sides for Portrait Records under the name Neil Scott. One ballad, "Bobby," was a moderate hit, rising to No. 58 on the charts in Cash Box. Singing in an adenoidal tenor, Bogart told the story of a "lonely teenage girl" in a hospital, "unconscious in her bed," yet at the same time pining for her boyfriend—"oh Bobbee Bobbee"—who left town after the couple had a spat. Bobby returns in the nick of time to revive her.

Unable to duplicate the success of "Bobby" and needing work, Bogart landed a job at an employment agency. One day Cash Box asked him to send some applicants for ad salesman, and Bogart went over himself. He kept nagging the magazine to hire the man he had sent, and soon had his first job in the record industry. From Cash Box,

Bogart moved to MGM Records as a promotion man, and then, in 1967, to Cameo-Parkway Records in Philadelphia as vice president and sales manager. He soon feuded with the company's owner, however, and left to join a new label called Buddah, where he was made general manager. Bogart was twenty-four.

Within a year, Time magazine was hailing Bogart as the king of "bubblegum," a reference to a new rock genre aimed at eleven-year-olds. Bubble gum was a reaction against the socially conscious acid rock of groups like the Jefferson Airplane. Bogart told Time, "We are giving kids something to identify with that is clean, fresh, and happy." Buddah's two biggest bubble-gum groups, Ohio Express and the 1910 Fruitgum Company, were in reality some studio musicians.

Both "groups" had the same lead singer, Joey Levine. Some of their big hits included "Simon Says," which sold 1.7 million copies,

"1, 2, 3 Red Light," and a song that opened with the words "Yummy, yummy, yummy, I got love in my tummy, and I feel like a-lovin' you..." Buddah's estimated first-year sales: $5.8 million.

The success was short-lived, and for good reason. Since bubble gum was created in the studio by producers, it did not generate career artists. Once the fad died, so did Ohio Express and the 1910 Fruitgum Company. Bubble gum was a foreshadowing of disco, also a producer's medium, and it is no accident that disco yielded very few artists whose careers continued into the eighties. Bogart knew how to spot a trend and run with it, but he was not a record man. The only career acts on Buddah were Gladys Knight and the Pips, who had been lured away from Motown, and Curtis Mayfield, who wasn't signed by Bogart. Bogart's tenure at Buddah established him as a promotion maniac. His head of promotion, Buck Reingold, who was also his brother-in-law—nepotism was another Bogart trait—was equally driven. At the time, the most important Top 40 station in the country was WABCAM in New York, and its director of programming, Rick Sklar, was a hard sell. One time, Sklar recalled, Reingold ambushed him in WABC's men's room with a battery-powered phonograph playing the latest Buddah 45. Another time, he trailed Sklar in a rented limo as he walked to work, blaring a new single through a mounted loudspeaker.

The disco era ended for the music business with a wave of unsold records sent back to distributors.

In 1973, Warner Bros. Records made a deal to bankroll and distribute a new Bogart label. In September of that year, Bogart quit Buddah to start anew as a Californian. Casablanca began with fourteen employees, each with a Mercedes.

Casablanca's first year was distinguished by the signing of the rock band Kiss, a harbinger of the heavy-metal groups of the eighties. Kiss's four members wore satanic costumes and makeup before there was MTV, and the visual appeal of the group was crucial to its popularity. The band had signed as managers the team of Joyce Biawitz and Bill Aucoin, mainly because they had produced a music-television show in the early seventies. At the time, Kiss was playing bars in Queens and had no recording contract.

Neil Bogart had been a guest on Biawitz's TV program, and she brought the group to his attention. He was fascinated by the theatrical aspect of Kiss and signed them immediately. Joyce Biawitz soon became the second Mrs. Neil Bogart, and the two of them started haunting magic shops and loading up on special effects. They hired Presto the Magician to come to the office and demonstrate the art of fire breathing. When Gene Simmons of Kiss tried to duplicate the trick, Joyce Bogart recalls, he scorched her newly painted walls black. Neil kept some effects for his own use. He once went to a promotion meeting at Warner Bros, and announced, "Kiss is magic," sending a puff of smoke from his hand.

The Warner people weren't so sure. Not long after Casablanca signed Kiss, Warner threw a party at the Century Plaza Hotel and invited the group to perform. When Kiss came out in their rhinestone shirts and makeup, says Bogart's then right-hand man, Larry Harris, "some of the Warner people were in shock." Little by little, Bogart began to resent that Warner did not share his enthusiasm for the band. The final straw came when he intercepted a cable on Warner's promotion hot line that said, in effect, don't bother to promote Kiss, because radio isn't going to play them anyway. "He went crazy," a former employee recalls.

Late in 1974, Bogart asked that Warner release Casablanca from its contract. Casablanca would go private, use independent distributors, and do its own promotion. This was fine with Warner, understandably, since Casablanca hadn't come up with a hit in eighteen months.

Casablanca flirted with bankruptcy for a year. Its first post-Warner album was called Here's Johnny: Magic Moments from the Tonight Show. Bogart promoted it so heavily that his independent distributors ordered massive quantities. The demand did not match the supply, but because the distributors had put in for so many copies, Casablanca had the cash flow it needed to survive until its luck changed. A gargantuan flop kept the company going.

A short time later, Bogart met Giorgio Moroder, an Italian record producer who had settled in Munich. There Moroder had found Donna Summer, a gospel singer from Boston married to an Austrian actor she had met while touring with the road company of Hair. After using her as a backup vocalist, Moroder gave her a solo called "Love to Love You Baby" in 1975. It was a novelty record—sort of a simulated orgasm. Moroder and his partner, Pete Bellotte, released the record on their Oasis label. Around that time, Moroder signed a deal for Casablanca to market Oasis in the United States.

Bogart put out "Love to Love You Baby," but it failed to arouse interest at first. Then, one night, legend has it, he was at a party where people were dancing to the Summer single and asking that it be played over and over. Bogart called Moroder in Germany and requested an extended version of "Love to Love You Baby." The new version clocked in at just under seventeen minutes. It became a favorite at New York discos, and then Frankie Crocker began to play it on WBLS. Donna Summer was suddenly very big, and her record had helped give rise to a fairly new format, the EP, or extended-play single, one of the most enduring vestiges of the disco era.

By 1976, Casablanca was hitting on all pistons. Donna Summer was hot. Kiss was hot. A funk group called Parliament, signed two years earlier, was hot. Meanwhile, Bogart enlarged his empire by merging his record label with a film company owned by his old friend Peter Guber to form Casablanca Record and Film Works. In 1977, PolyGram Records dished out a reported $10 million to become half-owner of Casablanca. That year Casablanca had gross revenues of $55 million. All in all, PolyGram thought its investment was the steal of the century. It was in for a surprise.

It is difficult to imagine any record company more unlike Casablanca than PolyGram. The latter was created in 1962 as a European classical-music unit in an exchange of shares between two industrial giants: Siemens A.G., a maker of electrical equipment, and Philips, a manufacturer of audio hardware. Philips contributed its namesake classical label; Siemens had Deutsche Grammophon. But soon after its creation, PolyGram entered the U.S. pop market and by the mid-seventies had gone on a buying binge, acquiring MGM Records, Verve, and the United Artists distribution system. With the U.A. purchase, the die was cast. PolyGram had to build its pop-market share, because even its classical output, the biggest in the world, was not enough to keep a national distribution network running. In 1976, PolyGram bought 50 percent of RSO, the only disco label that could rival Casablanca, which it acquired half interest in a year later. Meanwhile, it set up an American branch of Polydor, its European pop label.

It was never entirely clear who was in charge of PolyGram, though there was a nine-member board of directors that answered to both Philips and Siemens. The best analogy for PolyGram was probably the Dutch guilds of the sixteenth century. Nobody at PolyGram was an owner; everyone worked for a salary and retirement benefits. The American arm of the company was run from Hamburg by a man named Werner Vogelsang. PolyGram's worldwide leader, Coen Solleveld, was a reserved Rotterdam native with a white handlebar mustache. Solleveld had been imprisoned by the Germans in World War II. The other top decision-makers at PolyGram were Wolfgang Hix and Kurt Kinkele. Hix was short, Teutonic, soft-spoken, and a lawyer by training. Kinkele was more gregarious. Neil Bogart and the other Casablanca people liked Solleveld immediately. But, being Jewish, they found it hard to suppress a dark thought when they met the Germans: Where was he during the war? With Kinkele, it was not necessary to ask. His favorite icebreaker on meeting an American was to brag that he had caught his first glimpse of the United States through the periscope of the U-boat he commanded. Kinkele thought this was simply hilarious.

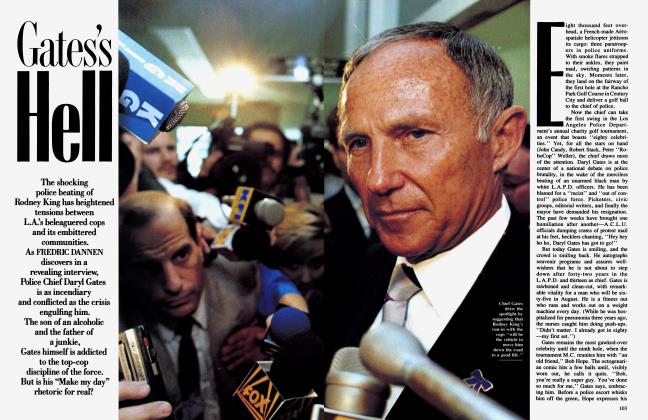

Casablanca's headquarters on Sunset was a Moroccan-style fun house that rocked with mega-sound amplification and rolled with controlled substances.

The story of RSO, which was created by Robert Stigwood—an Australian who began as a gofer for Brian Epstein, the manager of the Beatles—parallels that of Casablanca. But the crucial difference, perhaps, is that RSO's biggest successes—the movies Saturday Night Fever and Grease and their soundtrack albums—were so phenomenal that they covered RSO's losses. Though the company was suffused with "Whatever It Takes," it managed to beat the house odds, and in 1978, two years after it had acquired its half-interest in RSO, PolyGram tasted success beyond its wildest dreams. It was an annus mirahilis. Saturday Night Fever and Grease each grossed more than $100 million at the box office; Grease became the biggest movie musical of all time. The soundtrack albums of the two movies sold about 30 million copies apiece worldwide, an all-time record that would not be surpassed until Michael Jackson's Thriller. RSO began the year with five back-to-back No. 1 singles, by Player, the Bee Gees, Andy Gibb, the Bee Gees again, and Yvonne Elliman.

Casablanca tried to match RSO at the box office with a film about a riotous night at a discotheque, Thank God It's Friday. Neil Bogart came up with the story. The critics panned it, but it drew crowds and won a Best Song Oscar for Donna Summer's "Last Dance." Meanwhile, Casablanca hit pay dirt with a Peter Guber film, Midnight Express. And Bogart's company sold millions of records by Donna Summer, Kiss, and the Village People.

When PolyGram toted up the year's sales in recorded music, it came to $1.2 billion. No record company had ever topped a billion in annual revenues before, and PolyGram was euphoric. Its market share had jumped an astonishing fifteen points, from 5 percent to 20 percent. "All of a sudden," one PolyGram executive said, "we were right up there with CBS and Warner."

In mid-1979, PolyGram threw itself a huge bash in Palm Springs to celebrate, even hiring Henry Kissinger as an after-dinner speaker. Had the DutchGerman brass taken a closer look at the financial results, they would not have been toasting a victory. For all the money PolyGram was grossing, the profit margin was alarmingly slim. If you took away the two big sound-track albums, the U.S. operation was barely profitable, in spite of the other hit records. Though market share was way up, it was mostly a result of the two 30-million sellers, a feat that PolyGram could not expect ever to duplicate.

Even in 1978 there were signs that Casablanca was out of control. Bogart issued four Kiss albums at once, each a solo effort by one of the group's members. "Neil ended up selling 600,000 or 700,000 of each guy, which would have been enormous," says a former PolyGram executive. "But he pressed so many that we were getting killed on the returns. We were already way behind in September, yet Neil persuaded everyone that Christmas would take care of it. So he pressed another quarter-million and lost even more!"

There were danger signs at RSO as well. In 1978, Stigwood made a movie of the classic Beatle album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. It starred the Bee Gees, Peter Frampton, and George Bums, and it bombed. The two-record set of music from the film was voted the worst album of the decade by Rolling Stone. Yet the Bee Gees were so popular that the record would have qualified as a monster hit had it not been overshipped. "It sold maybe 3 million records," says a PolyGram alum, "but we shipped out 8 million and got back 5." The millions of leftovers were finally sold to a cutout distributor for twentyfive cents apiece.

In its euphoria, PolyGram so misread what had happened that it imagined it was the equal of CBS and Warner. It began to build its distribution network to handle the volume of sales it had had in 1978. PolyGram opened huge automated depots in California, New Jersey, and Indianapolis. When 1979 came around and there was no Saturday Night Fever or Grease, the depots were hemorrhaging an estimated $7 million a month. Looking back, rueful PolyGram executives would often use a plumbing analogy. "We built a six-inch pipeline," one said, "to find out later that we could only fill it with two inches of product."

The crash of '79 was at first a retailing phenomenon. The record industry had never imposed limits on the number of records that stores could return. This meant, in effect, that retailers had no inventory risk. They could accept shipments of any size, knowing they could return any unsold albums or singles for full credit. This was also true of the rack jobbers, the wholesaler middlemen who got rack space for records in department stores. Coen Solleveld, who had moved to New York and was learning the American marketplace, was baffled by this. "If I were a wholesaler or retailer," he told the Los Angeles Times, "I would laugh all day."

The laugh was on the entire record business, without a doubt. All the major labels had caught disco fever and were shipping vast quantities of dance and pop albums on the basis more of egotism than demand. The retailers took them. Why not? In 1979 the records started to come back by the steam-shovelful. And even though the market had shrunk drastically, Casablanca and the other PolyGram labels continued to sign new acts by the score. Before Bogart was through, Casablanca had a hundred pop acts under contract—more than CBS Records. Each signing cost $100,000 or so, before promotion. Add to that the expense of running the vast automated distribution system that PolyGram had built in the United States to handle all the monster acts it was supposed to have, and it is obvious that the profit drain was becoming a sinkhole.

"I'd be looking for a secretary, and there she would be with a credit card in her hand, chopping, chopping the coke on the table."

Casablanca began to lose tens of millions a year. It had two hundred employees on salary, and a large drug budget. In 1979 the Village People were played out, Kiss lost some popularity, and Donna Summer was about to leave Casablanca for Geffen Records.

Finally, PolyGram decided to make one of its own people Casablanca's chief financial officer. It chose a young accounting executive from Polydor, David Shein, and sent him to Los Angeles. A short time later, a PolyGram executive visiting L.A. found Shein behind the wheel of a Mercedes convertible that Neil had let him use. The accountant had become a Bogart ally. "Neil had a unique way of co-opting people," Shein admits in retrospect. "It was real hard not to believe what he said."

Shein's replacement, Peter Woodward, did not work out for PolyGram, either. "I asked to see the guy, because he had overpaid some bills, and I wanted to know why," remembers David Braun, a former executive at PolyGram's headquarters in New York. "In walked a guy with a necklace and chain around his neck. When I asked him why certain things hadn't been done to regulate the payment of bills, because they had lost a fortune, he gave me some speech about how hard his team worked. And they were really tired—I remember his words—with 'assholes from Central,' meaning me, coming in to criticize them!"

Bogart soon had troubles of his own. In October 1979 his mock-Tudor mansion in Holmby Hills burned to the ground. Then, in February 1980, Donna Summer filed a $10 million lawsuit against him, his wife, and Casablanca, claiming she had been financially defrauded. When Bogart brought Summer to the United States in late 1975, she did not have a manager, and in the best tradition of the record business, he provided one for her: Joyce Bogart. Summer alleged that every attorney who represented her was chosen by Neil or Joyce and did legal work for Casablanca.

The same month that Summer filed her suit, PolyGram bought the 50 percent of Casablanca it didn't already own and forced Neil Bogart out. It was not a bad way to be got rid of: Bogart was Casablanca's principal stockholder and received most of the buyout price, a reported $15 million. He used some of the money to start a new label, Boardwalk, which introduced rock singer Joan Jett and sold several million copies of her album / Love Rock 'n Roll. Casablanca FilmWorks was spun off and became the basis of the newly formed PolyGram Pictures, which went on to make some commercially unsuccessful movies, including Missing and Endless Love.

In May 1982, Neil Bogart died of cancer of the kidney and colon, possibly aggravated by drug abuse. He was thirtynine. Though still in litigation with his estate, Donna Summer sang at his funeral. A year after his death, Boardwalk went under. PolyGram did not return to profitability until 1985, at which point it had lost more than $220 million in the United States. Casablanca was responsible for a major chunk of the deficit. The exact amount has never been disclosed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now