Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE LIFE OF RILEY

KEN AULETTA

Pat Riley, former star coach of the L.A. Lakers, is now pushing the resurgent New York Knicks into the upcoming N.B.A. play-offs— but will he push them too far?

Sports

Few employees of Paramount Communications picture their boss as a pussycat. In fact, Martin Davis likes to style himself one of "the toughest bosses in America," as Fortune once dubbed him. Yet around the New York Knicks, one of the many companies under his thumb, the notoriously brusque executive has always felt—he hates admitting it—a bit insecure, even meek. When he wandered down to the team's locker room after a game, Davis confesses, "I used to feel tense." The players didn't know who he was, so they ignored him. He felt like a jerk, so he withdrew, rarely going to games.

Away from Madison Square Garden, sportswriters and columnists heaped scorn on Davis and Paramount for butchering their basketball and hockey teams. Every year the Knicks and New York Rangers deflated their fans, and Davis, who is not knowledgeable about sports, didn't have a clue how to fix it. "I used to blame myself," he admits. He was so gun-shy that he became invisible to major figures in the teams' management. It sounds unbelievable, but he does not remember ever meeting either former Knick coach Rick Pitino or general manager A1 Bianchi.

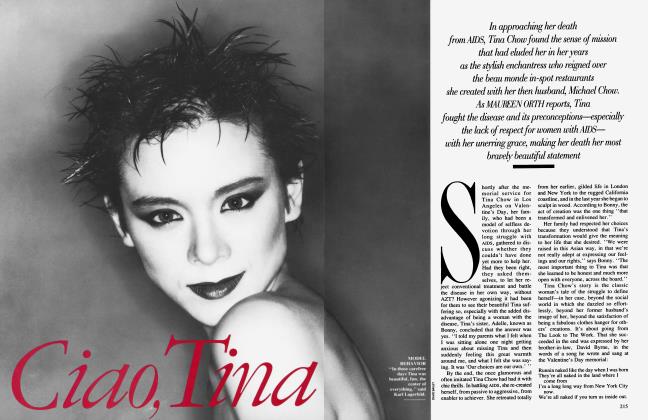

But this season would be different, Davis vowed. So there he was, leaning forward in his courtside seat across from the team bench, enthusiastically pounding his palms together for the Knicks at their November home opener against the Milwaukee Bucks. The Garden was buzzing. There were over 15,000 fans in attendance, more than a few Hollywood notables, and every eyeball was riveted on the new star of the Knicks, who neither rebounds nor scores points: Pat Riley, the slick-haired man languidly pacing the sideline in his double-breasted navy-blue Giorgio Armani suit.

In New York, forty-seven-year-old Pat Riley is treated like a cross between a rock star and a cavalry officer: women swoon and men want to follow him into battle. It is the way he was regarded in Los Angeles, where he coached the Lakers to four world championships in nine years. Riley's Lakers became synonymous with "Showtime," glamorous, high-flying basketball displayed by one of

the greatest teams ever to run a fast break. And Riley was the ultimate L.A. coach, tanned and Tenaxed, sporting oxfordcloth shirts he designed himself (tailored in Hong Kong) and driving to work from his home in Brentwood in a mint-condition charcoal-gray Mercedes sedan. During the games, while everyone else in the Forum was screaming and high-fiving, his icy demeanor made him the coolest guy in the place. Jack Nicholson and Michael Douglas sat nearby, craning their necks to watch him; screenwriter Robert Towne modeled the Kurt Russell character in Tequila Sunrise on the Laker coach.

But despite his high profile and the star-level adulation he's received in L.A. and New York, Pat Riley feels like a stranger to many of those who watch him work. "People don't know me at all," sighs Riley, who at practices wears sweat suits and the unshaven, holloweyed look of a gym rat. "They've always written about 'Showtime' and glitter and glitz and clothes and my hair and gel. It's always been that. They've always missed the substance of what the Lakers were, which was a work-ethic team."

Pat Riley crouches along the sideline in front of the Knick bench as if in silent prayer. His Knicks are on the road, engaged in a pitched 128-126 double-overtime battle against the fierce Atlanta Hawks. If they stumble, Riley fears, his team may also lose the wobbly self-confidence he has worked so hard to instill. So when Knick guard John Starks launches a long-range bomb, Riley holds his breath. The stadium freezes as the ball rotates toward the basket. When it rips through the net, capping an epic upset, Riley stands, lets out a loud war whoop, and kicks a leg in the air like a Rockette.

In fact, the never contented coach is so enthused that, for the first time this season, he stations himself at the tunnel leading to the locker room so he can congratulate each Knick with, yes, a smile. "That was just an unbelievable game for us," Riley says after coming out of the locker room, his jade-green Armani tie surprisingly askew.

"It was a gut-wrenching game, but it seems like we're developing some resiliency.''

Even when he pumps up the volume, Riley understates the case. Through the first half of the 1991-92 season, Riley's Knicks have astonished Martin Davis and Knick fans. By the February AllStar Game, the once dismal team had racked up an impressive 30-16 record, was in first place in its division, and was charging toward the N.B.A. play-offs, which begin in late April. The new coach had succeeded in schooling the Knicks to take fewer dumb, off-balance shots, to work the ball in to their one true star, center Patrick Ewing. He had inspired them to play a ferocious team defense, compensating for a two-cylinder offense. He had carefully rebuilt the shattered confidence of the team's quarterback, point guard Mark Jackson. He had drilled shooting guard Gerald Wilkins to tame his wild playground style, and had coaxed power forward Charles Oakley to stop shot-putting the ball at the basket and settle for the unglamorous rebounds the team needed. Somehow, Riley had persuaded all twelve players to surrender the greedy glory of individual statistics for the innocent satisfaction of winning.

One way to measure how a Pat Riley team is doing is to count the famous faces in the courtside seats. Suddenly, Madison Square Garden is hosting a small constellation of stars, not just such long-suffering Knick fans as Woody Allen, Richard Lewis, and Spike Lee. Kathleen Turner has popped in, as have Bugsy director Barry Levinson, Matt Dillon, Rob Lowe, and even Blaine Trump. Pat Riley's wife, Chris, who long ago gave up her own career as a family therapist to accept the role of team wife, has been doing her part to manufacture the buzz by telling friends, including movie publicist Peggy Siegel, that she controls a block of house seats which can be set aside for celebrities. "The movie stars and the directors all want to go to games and see what Pat's doing," reports Siegel.

What is Pat doing? He's pounding into his players' heads the same motivational mantras that punctuate the speeches he's delivered to corporate audiences for up to $20,000 a pop. Riley's strictures sound cliche, but his force of personality makes them come alive: Thou shalt think of the team, not thyself. Thou shalt hustle. Thou shalt not whimper. Thou shalt sacrifice all worldly pleasure and glory to get to the promised land.

Can Pat Riley bring a championship to New York before his players become fatigued by his almost messianic intensity?

From the beginning, the implicit leap of faith asked of the players and fans was to believe an inspired coach could remake a team of only modest talent. So far, Riley has delivered.

So far. But now the half-converted are asking the next question: Can Pat Riley bring a championship to New York before his players become fatigued by his almost messianic intensity?

His players both respect and like Riley, but he rarely lets up on the team. He runs grueling three-hour practices that are scripted down to the minute. He evaluates every one of his athletes incessantly, using a whole new category of statistics he has invented that goes beyond box scores to measure every player's effort on every play. He screens hours upon hours of videotapes of the Knicks and their opponents—two or three times. He hunts through Shakespeare and Sun-Tzu for quotes to inspire the troops. He privately scolds players for shoddy performances; when upset, he has even yanked his one superstar, Patrick Ewing, from the game. He's such a perfectionist that when the team arrives at a hotel at 2:30 A.M. the team trainer immediately plugs in a VCR so that the coach can stay up a few hours watching tapes of the next opponent. He worries about his team so much that he often drops ten to fifteen pounds during the pressure of the play-offs; in January, he had to take sleeping pills for insomnia. Even the N.B.A. commissioner thinks Riley goes overboard: he fined the Knicks $10,000 when their coach ran his players through an illegal extra practice on New Year's Day.

Not surprisingly, Riley's monomania is not applauded by everyone around the Garden. Already there is scattered grumbling, though not from the players or Knick management, who are certain he's the best coach in basketball. "Everyone respects Riley, but very few like him," says one Garden executive not connected with the team. "Pat is his own company. He demands that no one may walk in the arena when the team is there, that no one may travel on the team plane or bus. ... I have to reintroduce myself to him every time I meet him. He behaves like a superstar. ' '

Riley admits his white-hot intensity can bum out those around him. In fact, it was the reason he left the Lakers. After nine seasons, what he calls "toxic envy" had set in. Personalities rubbed one another raw, once fresh motivational lectures were met with rolling eyes, success eroded the willingness to sacrifice and resurrected dormant selfishness and jealousies. It's inevitable, he says with equanimity. "It will happen here."

So, before "toxic envy" hits New York, can Riley win a championship with these Knicks?

According to Riley and the Knick brain trust, the brutally honest answer is no. The premier teams—the Chicago Bulls, the Portland Trail Blazers, the San Antonio Spurs, the Golden State Warriors, the Utah Jazz, the Cleveland Cavaliers, the Phoenix Suns, and the Lakers, until they were deflated by Magic Johnson's sudden retirement after testing positive for the AIDS virus—have what Riley calls "a talent cushion." Each has two to three players who rank among the top eight players in the league at their position. The Knicks have only one—Patrick Ewing. Publicly, Riley has nurtured the confidence of his young men, raining praise on Mark Jackson and Gerald Wilkins and Charles Oakley. Privately, he knows the Knicks have too many glaring deficiencies. "We don't have the talent cushion here yet," observed Riley early in the season. "Nor am I sure we have the attitude here yet. "

The team's (Continued on page 114) (Continued from page 108) brain trust hasn't been deluded by early successes. On January 7, when he heard that thousands of Knick fans were lined up at the Garden, fans who would purchase $500,000 in tickets to future games, New York Knick president Dave Checketts brought hot coffee and muffins down to them. As the six-foot-five-inch executive strolled through the crowd, he heard fans exclaim, "You're going to win a championship!"

No way, thinks Checketts: "The team is somewhere between people on one extreme who say, 'The Knicks are just a mirage,' and the other extreme, which are these people who bought more individualgame tickets than ever in the history of the Garden." The truth, says Checketts, is this: "I know we're at least two players away. We need a backcourt player who can shoot, an all-star-caliber player for the number-two spot [shooting guard]. And we need a very athletic frontcourt player who plays big forward and who can play backup center."

In other words: Goodbye, Gerald Wilkins, a sometimes spectacular athlete who team officials believe too often lapses into undisciplined playgroundstyle basketball. Good-bye,

Charles Oakley, who can outmuscle enemy rebounders but rarely scores and has a reputation for sulking.

And, though it will come as a shock to him and to many fans, good-bye, Mark Jackson. Despite the point guard's vast improvement under Riley, there is a consensus among club officials that Jackson will never lead the Knicks to a championship. "We need a point guard to score," explains an important team insider. "We need him to defend and to make huge plays at the end." No matter his strenuous efforts over the summer to reduce his body fat by working daily with the team's conditioning coach, no matter his newfound maturity, his dazzling passes, or Riley's praise. Deep down there is a rock-hard conviction among Knick strategists that Jackson is cursed. He cannot lead this team because, whether it is his fault or the other players', the other Knicks don't trust Jackson enough to follow him. A high Knick official says pointedly, "A change of scenery would be fantastic for Mark. ' '

All of this raises the question: Is Pat Riley lying to his players?

In one sense, he is. True, he tells Jackson that he needs to work harder on defense, and tells Wilkins he has to stop hotdogging, and tells Oakley to forget about shooting the ball. And he doesn't blow smoke in their ears, the way former Knick coach Rick Pitino used to, telling players they were the best in the league. But he's also not telling them the whole truth: that he doesn't believe they can take the Knicks past the first round or two of the play-offs.

Riley is not an uncomplicated man. He understands that a leader operates on several different levels simultaneously—and that followers operate on a need-to-know basis. Which is one of the many reasons the Knicks reached out to Pat Riley in the first place.

Last season, the Knicks lost more games (forty-three) than they won (thirty-nine), and by midyear Martin Davis was deeply embarrassed. They had suffered eleven losing seasons in the previous seventeen. "The team," summed up veteran Kiki Vandeweghe, "was in the habit of losing." Nancy Grunfeld, the wife of vice president of personnel Ernie Grunfeld, was blunter: "Coming to this place last year was like a shivah call."

"Madison Square Garden was not a priority, as was Paramount Pictures and Simon & Schuster," Davis explains from his meticulous, glass-walled fortysecond-floor office in the Paramount building overlooking Central Park. "People blamed Paramount, but it wasn't true. Now they can blame the forty-second floor."

By early 1991, Davis was already talking to producer Stanley Jaffe (The Accused, Fatal Attraction, and Kramer vs. Kramer) about coming aboard as his heir apparent. The first task for the New York—bred Jaffe, a lifelong Knick and Ranger fan, would be to fix the mess at the Garden. In the meantime, Davis and Dick Evans, then president of the MSG Corporation (which oversees the Knicks), approached their choice for the new president of the Knicks: Dave Checketts, who had built the Utah Jazz into a powerhouse in the mid-1980s.

Checketts, then vice president of development for the N.B.A., missed the action of piloting a franchise. He had turned down the Knick presidency in 1987, but this time the Knicks were promising him real power. It was tantalizing. But first Checketts undertook a clandestine mission. He would not accept the job, he reveals now, "unless I knew I could get Pat Riley as coach. There is no other coach in the same class."

Checketts called Riley, who was then working side by side with Bob Costas as a $500,000-a-year basketball analyst on NBC. They already knew each other, and a lunch was not unusual. They met at the Regency Hotel on Park Avenue, where Riley stayed when he came to New York. It didn't take long to realize they were kindred spirits. For Checketts, like Riley, also reveres intangible qualities. "If you have two players that are equal," Checketts says, "you should always take the player who has more character. If I had to choose, I'd take a player with 20 percent less talent if he has more character. ' '

When the two men finally swung around to the subject of Riley's new career as a TV analyst, it seemed clear to Checketts that Riley was unfulfilled. Broadcasting seemed a dead end. Riley was even thinking of getting into the movie business, and had taken acting lessons (when he was coach of the Lakers, he had turned down the offer of a film role from friend Robert Towne). "He wasn't about to be a 'character' on television like John Madden, nor a clown," explains longtime friend Michael Fuchs, chairman and C.E.O. of HBO. "Nor was he going to be glib and spontaneous like Bob Costas." In fact, Riley didn't particularly like the direction the network was trying to steer him.

"He used to complain a little bit about the things NBC expected of him," says childhood pal Ben Jacobson. "They wanted him to be 'controversial,' and to criticize other coaches or players. That's not something he wanted to do."

When the moment was right, Checketts broached his secret: "Pat, if I ever decide to run a team again, and I think I'm going to be given an opportunity, would you consider getting back in?"

"If it's the team I think you're talking about," Riley answered, "absolutely."

"I never doubted that he would take the job," Checketts says now. "This guy still has fire—like I do. And he hated what he was doing—as I did."

Checketts' appointment as Knick president was announced on March 1, 1991. That same day, he telephoned Riley to say, "I haven't forgotten our conversation." Riley had not either, he assured Checketts, but out of respect for Knick coach John MacLeod, Riley said they should not speak again until MacLeod's fate was resolved.

A solid, experienced coach, John MacLeod was also a gentleman. But, as Knick vice president John Cirillo says (speaking generically), "it's not enough to be a good coach—the players have to believe in you." So Checketts told MacLeod that, until he evaluated things, he was unprepared to give the coach the contract he wanted. Several days later, when the athletic director of Notre Dame called MacLeod to offer him a five-year contract, MacLeod went to Checketts to explain that he didn't know that he could turn it down. Checketts said he understood. The new Knick president, who was determined to treat MacLeod with the dignity the Knick front office often denied its employees, never told MacLeod that Checketts was the one who first slyly planted the idea with the Notre Dame A.D.

Next came the chase to get Pat Riley. They met secretly on May 11 and, to avoid the press, continued their furtive negotiations over the next several weeks in various hotel suites. They discussed Knick weaknesses, the crowded pointguard position, the desperate need for outside shooting. They talked about Patrick Ewing, who was trying to exercise a clause in his ten-year, $30 million contract allowing him to become a free agent if four or more N.B.A. players raked in as much as or more than he did. The Knicks were insisting that only three other players topped Ewing's salary, and an official arbitrator was pondering the case. Riley, who the year before had called Ewing the best center in basketball, wanted assurances from Checketts that the team's sole star could not exit.

The two men also talked contract terms. Granting Riley a say over trades and draft picks was easy, though Riley suggests he was given veto authority and Checketts says that as president he retains the ultimate power. Because the two men had such a friendly rapport, this did not become a point of contention. What did were the financial terms. Initially, Riley approached the table like a movie star: associates say he asked for $2 million a year in salary plus incentive clauses, plus a book contract with Paramount's Simon & Schuster, plus a mortgage-free house, plus a deal with Paramount Pictures to produce and perhaps even write and direct movies. "He started off unrealistic about what they would pay him," admits Riley's friend Ben Jacobson. Which is one reason Checketts began interviewing three other candidates.

Riley asked for $2 million a year, plus a book contract, plus a house, plusa movie deal with Paramount Pictures.

In the end, according to an official who knows, Riley settled for a five-year contract worth a total of just over $6 million in salary, plus "typical" incentive clauses for each round of the playoffs the Knicks win—no book contract, no movie deal, no house. Checketts did agree that when the team was in New York it would stay at the Regency Hotel, where Riley received a free suite in return for promoting the hotel. And Riley was also handed a few Garden-related endorsement deals, though none presumably as attractive as the long-term deal he has had with old friend Giorgio Armani that provides him with a free wardrobe and has presented Chris Riley with more than a few outfits of her own.

Pat Riley's initial task, as he saw it, was to wiggle his way into his players' heads. His first meeting was with the troubled point guard, Mark Jackson. The onetime Rookie of the Year, now entering his fifth year in the N.B.A., would be Riley's chief reclamation project. After his surprising first season, Jackson's swollen confidence had plunged him into a nosedive which he had not been able to pull out of. His most recent year was his worst: he had been booed and benched regularly. Knick officials had muttered to the New York newspapers that Jackson didn't jump well and was slow-footed, that he showboated with "theatrical" passes, that he didn't think of the team first.

The Knicks announced that there would be a wide-open, three-way competition among Jackson, twenty-six, Maurice Cheeks, thirty-four, and firstround draft choice Greg Anthony. But Riley now reveals that he presented a different picture to Jackson in June when the door to the coach's cramped Garden office was closed.

"I have listened to everybody around here," Riley told Jackson solemnly. "There isn't anyone who doesn't think you should be traded." He let that sink in before he continued. "But you're my starter. If you don't start, there will be nothing but controversy. So this year you will either start or you will be out of here. ' '

It was a statement that would have stunned most of the other players and nearly all the Knick fans if they'd known about it. But, as Riley explains it now, it was a chess move born of pure reason. He had studied for this face-to-face as carefully as he prepares for every opposing team. The statistical breakdown from the previous year revealed that, despite his shortcomings, Jackson was the top-rated point guard off the bench in the N.B.A. Logic told Riley that he could not build a team around a thirty-fouryear-old athlete like Maurice Cheeks or a rookie like Greg Anthony. Riley actually had no choice but to award the ball to Jackson. He didn't say this to the sensitive point guard, of course. All he said was You're my guy. The young athlete's withered confidence began to revive.

Riley custom-tailored his remarks to fit each Knick. He told Patrick Ewing that he was a "proud warrior" who could lead the team. Ewing worked as hard as any athlete he knew, Riley said, but he was not a leader in the locker room, the way such stars as Magic Johnson or the Chicago Bulls' Michael Jordan were. Instead, the quiet seven-footer led by example—which on a young team was not enough. Now his whole focus, Riley told him, had to be on what it takes to win. "Most players come into this league with a Me mentality," says Riley. "You've got to let them go through it. One day they realize that they are miserable even with all the dollars and the fame because they are not a winner. They have no inner peace. That's the next level for him."

Some players Riley wanted to liberate, like Ewing and Jackson. Others he wanted to handcuff. With six-foot-nineinch forward Charles Oakley, a powerful rebounder but a poor shooter, Riley's task was to get him ''in the right spirit" to accept a reduced offensive role. The core of what Riley told Oakley, and all the others, was selflessness.

At the October training camp, Riley announced that he would be monitoring their team play with his "effort statistics." Video coordinator Bob Salmi and a staff of four would chart each scrimmage and game and deliver to Riley and his three assistant coaches a videotape and a computerized plus/minus report comparing each player's hustle with his opponent's. As a result the coach would be able to count not just how many points or rebounds they notched but how many times they dove headfirst for a loose ball, passed off to the open man, boxed out an opponent, covered for a teammate on defense, or jumped for a rebound even if they didn't get it. Sixty-one-year-old assistant coach Dick Harter says that, un-

der Riley, "there are more statistics kept on this team than on any other."

What the new coach was determined to do was to quantify the unquantifiable: attitude, teamwork, sweat. Although his Laker teams were known for their flash and dazzle, their thundering fast breaks and precision passing, their foundation was always fearsome team defense and ruthless rebounding. "You can't run if you don't rebound the ball," says Riley, laying down another immutable law. "In this league, no one runs for fortyeight minutes. You want to develop a period of three or four 'skirmishes' that can result in three or four 12-2 or 8-0 'runs' that are bom out of defensive pressure, initiative, and big plays that will lead to fast breaks. If you can win three out of four of those major skirmishes during a game, you will win most of those games."

To win more skirmishes Checketts and Grunfeld snatched small forward Xavier McDaniel in a trade with the Phoenix Suns. "The Knicks finally got a tough guy, a leader," declared Jim Karvellas, the astute Knick radio play-byplay man. Even before the season started, McDaniel was heralded as a savior. (Of course, three years before, Charles Oak-

ley had been hailed in similar fashion.)

Over the next two months, the Knicks hacked their way through eleven straight victories at home, roaring into the new year with a startling 18-8 record and the top spot in the Atlantic Division. From opening day, the team gathered around its new coach as if he were Father Riley leading them in prayer. In huddles, all twelve players, not just the five starters, keep their eyes fixed on the coach. Mark Jackson gushed to The New York Times, "It's great to have somebody who believes in you." The normally shy Patrick Ewing was shouting encouragement on the court, slapping palms and bumping chests to congratulate teammates, smiling more. (He had more reason to smile: in November the Knicks agreed to add two more years to the four years remaining on his ten-year, $30 million contract; they will pay their franchise player $33 million for the next six years, a jackpot of $48.8 million over Ewing's twelve years with the Knicks.)

There was another change in Ewing: he calls Riley "coach." The star center had addressed every one of his four previous coaches by his first name. "Patrick has only bestowed the title of coach on two people," observes Checketts. "One was John Thompson, at Georgetown. The other is Pat Riley."

"Coach never changes his tone of voice," says 250-pound backup forward Anthony Mason, who along with fellow free agent John Starks has been a prime example of overachievement through relentless effort. "He never singles out anybody for criticism. He makes a player want to play for the coach."

Asked what was different about the Knicks under Riley, Boston Celtic legend Red Auerbach gruffly waves an unlit cigar and growls, "They found out they can win. He has them thinking positive. They're scrappy. They go after every loose ball. They're playing better defense. They are utilizing Ewing's greatness."

Inevitably, though, Riley's Knicks seemed to fall back to earth. From the day after Christmas through January 27, the Knicks were 9-8. They did rack up five straight at the end of the month, including three out of four road games against such stronger teams as the Golden State Warriors and Checketts' alma mater, the Utah Jazz. But through early February the Knicks still had a losing record against teams with winning records.

How far can a team go on a leap of faith?

There has always been a chasm between the rock-star perception of the winningest coach in pro-basketball history and the reality. A few days after Christmas, Dave Checketts was surprised to learn that Riley was not spending a glamorous New Year's Eve with some of his presumed Hollywood pals. So Deb and Dave Checketts and Chris and Pat Riley met for a quiet dinner at Terra, a modest Italian restaurant in Greenwich, Connecticut, where the Checkettses, who are Mormons, clinked their glasses of cranberry juice with the Rileys' glasses of champagne.

Over pasta and broiled salmon, Checketts, who is thirty-six but could pass for a recently graduated college-fraternity president, mentioned that he had lost his father in 1988. Suddenly, a vein seemed to open in Riley, and out spilled memories of his youth in Schenectady, New York, and of his father. Lee Riley had always been, Riley said, a relative stranger. The six Riley children could describe their father's natty dress, or the neat way he slicked his hair straight back, but mostly they remembered him being away a lot.

Lee Riley's business was baseball, as an outfielder, pitcher, and first-baseman

in the Philadelphia Philly farm system, then for eight years as a manager of various Philadelphia minor-league teams, including the Schenectady Blue Jays. In 1952, after he was repeatedly passed over to manage the major-league Phillies, Lee Riley left the game. "When my father was released he threw out everything," Pat Riley remembers. "I had nothing of his." Tossed in the garbage were the uniforms, baseballs, photographs—everything a son could hang on to. To purge his disappointment, Lee Riley turned to alcohol.

The family finances slid as Riley's father opened a food-and-newspaper variety store. When that didn't pan out, he became a janitor at Bishop Gibbons High School. For the final few happy years of his life, he doubled as the school's baseball coach.

Throughout, Pat Riley remembers his father as a very strong figure, even fearsome. If his baseball team lost, everyone mourned. To toughen his son, Lee Riley ordered Pat's older brothers to take him to the basketball playground and match up against older gang members, who did not hesitate to smash an elbow in his face. Pat Riley learned to compete the hard way.

The son also learned about self-control. As a boy, Pat Riley had a ferocious temper—once, when he got beaten in a card game and lost one dollar, he punched a fist through the ceiling of Ben Jacobson's Schenectady basement. Today the volatile Riley temper, like the man, is under strict control. "He never shows misery or elation," says Jacobson, who now runs his own Manhattan investment firm and remains close to Riley. "He has his emotions in check." Well in check: Riley has never spoken of his father to his lifelong friend.

Spurred by Lee Riley and a succession of iron-willed coaches, six-footfour-inch Pat Riley drove himself to become an overachieving all-American at the University of Kentucky, and a first-round draft pick of the San Diego Rockets in 1967. He was twenty-five— and had just struggled through the third season of his scrappy nine-year pro-basketball career—when Lee Riley died suddenly of a heart attack.

Checketts says the New Year's Eve dinner was an eye-opener, giving him fresh insight into Riley. "It's a Field of Dreams story," says Checketts, whose own father's slow death from emphysema at least gave him time to spend with him at the end. "All of us want to have a resolution of the father-son thing," says Checketts. "Pat didn't get a chance to say good-bye, or even hello."

Pat Riley says he first heard his dead father's voice in 1985, the year after his Los Angeles Lakers were trounced by the Boston Celtics in the finals. It was the eighth time in eight championship finals that the Lakers had lost to the Celtics. The Lakers had "choked," Boston great Larry Bird said acidly afterward. Pat Riley agreed. In fact, the coach felt he was responsible. He accused himself of betraying too much emotion, of losing control by permitting the Lakers to match the more physical Boston team elbow for elbow instead of playing their own, balletic style. So Riley dedicated the next season to "gaining back our self-respect," and searching for ways to become a better coach.

One year later both teams were in the finals again—but the opening game continued the same horrifying pattern: Celtics 148, Lakers 114. Riley was desperate to jolt his players out of their daze. "I went to my wife, I went to books, to find a message' ' to inspire the team, he says. He wrote something up, but wasn't satisfied. Game Two loomed three days away.

Then Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the Lakers' all-star center, asked if his father, who was visiting from New York, could ride with them to Boston Garden aboard the team bus. Riley consented. On the bus, Riley couldn't take his eyes off the pair, noticing the respect the son accorded the father, the easy way they talked. Riley remembered the last time he had seen his own father, at his 1970 wedding to Chris in San Diego. As Lee Riley left the reception at the Town & Country Hotel, he leaned out the window of his car and told his son, who was worried about his stalled pro-basketball career, "Just remember what I always taught you. Every now and then there comes a time and place where a man has to plant his feet, stand firm, and make a point about who he is and what he believes in—and kick some ass."

When the Lakers arrived at Boston Garden, Riley gathered them in the locker room and did something unusual: he made his pre-game talk deeply personal. For the first time, he talked about fathers and sons, about how his father had fought back from failure and how he learned from his dad never to flinch, to stand with his back to the wall and kick some ass. The Lakers, electrified by their coach's heartfelt speech, made their stand: they won Game Two and, eventually, the championship.

What began to crystallize in Pat Riley's mind was the importance not just of talent but of what moves talent, of what might be labeled the Human Factor—motivation, attitude, intensity, and what he calls "a spirit of tolerance" that lubricates team chemistry, qualities Riley lumps together vaguely, almost mystically, as it. "I have seen talented players come into the N.B.A. with extraordinary skills," says Riley, "and I have seen less talented players forge ahead of those guys because they had an extraordinary attitude. You cannot have a team of twelve superstars."

The problem, Riley knows, is that in the N.B.A. all you start out with is superstars. Nearly every one of the league's 324 pros has been drenched in adulation from the time he was a teenager, most of them high-school sensations and many college all-Americans. They were rewarded with multimilliondollar contracts and bonus clauses. They are idolized by an entire nation on television in games and in ads, chased by flocks of reporters and photographers, and, in every city, by beautiful, young, available women. "Imagine if you had to coach a team of Michael Jackson, Bruce Springsteen, Dion, Paul Simon, and Billy Joel," says N.B.A. commissioner David Stem. "That's what it's like coaching in the N.B.A."

What Riley came to understand is that a coach has to develop a team's attitude, not just its muscles. For Riley, the true spirit of teamwork was embodied by Magic Johnson, who joined the Lakers in 1979. After Johnson played each position on the court—guard, forward, and center—in the 1980 championship game, headlines proclaimed: IT WAS MAGIC.

"It wasn't magic," says Riley. "It was Earvin Johnson." When Johnson was nine, Riley says, he had a coach who said he was so good that every time he touched the ball he should not pass it off to a teammate but should instead shoot. The team won, but the locker room after the game was morose. His teammates, who rarely scored, were sullen. Their parents were joyless. "So at nine years old," says Riley, "he learned one of the most important things in life. He had made a commitment that he wanted to be a basketball player. But he learned that when players feel good about themselves the team will be successful. It's very simple, but it's one of the most difficult things to teach."

"There isn't anyone who doesn't think you should be traded," Riley told Mark Jackson. "But you're my starter."

By the mid-eighties, Riley replaced his longish hair and thick sideburns with the slicked, straight-back hairstyle favored by his father. Riley became, remembers Abdul-Jabbar, "more selfconfident." To the Laker "family," Magic Johnson would say, Riley became "the patriarch"—Father Riley.

But Riley did not mellow; he became more and more driven. Practices swelled to three or more hours. He climbed inside the heads of his players, stoked their resentments against other teams, sometimes inciting them with anger, sometimes with pride. When they were knocked out of the play-offs in 1986, he challenged them to make the following season the Year of the Career-Best Effort.

With Magic Johnson, Kareem AbdulJabbar, and James Worthy leading the way, the Lakers were the dominant team of the eighties. In 1987, while they were still in the locker room celebrating their third championship of the Riley era, the coach stunned them by predicting they would repeat the following season—a feat that had not been accomplished in nearly two decades. Incredibly, the team rose to his bait, capturing the crown again the following year.

Dazzled by the Lakers' grace and glitz, what many fans and some sportswriters overlooked were the bleary-eyed hours the coach and his players put in, the obsessive fear of losing that drove the team as it had driven Riley from boyhood. "I've always been somebody," admits Riley, "who worried that someone would take away everything I have."

Eventually, with success and time, the Laker family ties began to fray. Riley used to refer to himself as "a tolerant tyrant," but some players thought the balance had shifted to the latter. To them, the Hollywood friends, the slicked hair and sleek jackets, and the exhausting repetition of practices and pep talks became tiresome. "The image worked against him after a while," recalls Jabbar. "We knew him earlier. He got into his style a little bit. He became a little more comfortable with his authority and began wielding it with a little less sensitivity."

Jabbar remembers the time that the L.A. Forum was being sued by a fan who had had an accident inside. Though Jabbar, Magic, and Worthy had not witnessed it, they had to drive together to Orange County to testify. They would have to miss practice, they told the coach. No way, replied Riley, who scheduled a team practice for seven A.M. "He became more rigid about stuff like that," remembers the Lakers' future Hall of Fame center. Particularly in the last two seasons, players complained that he would try to motivate by provoking them to anger. "It was like getting pissed off at your dad," says Jabbar. "You sulk. But unlike a dad, you can cut your link."

During the 1989-90 season, the first year Riley coached without the retired Jabbar, he pushed the team harder than ever. Michael Cooper, who was nearing the end of his distinguished career as a defensive specialist and long-range shooter, was upset at Riley's psychological tricks and his own reduced playing time. Cooper requested a meeting with general manager Jerry West, who mentioned this to Riley. No problem with a meeting if it's to talk over Cooper's contract or his future with the team, Riley responded coolly. Any discussions about Cooper's playing time, however, should be with the coach, not the general manager.

The sit-down between the player and the general manager turned into a gripe session about the coach. West called Riley to report that he had met with Cooper, listened to his laments, and agreed with some. "You got a problem," West told Riley, according to Riley intimates.

"No," retorted Riley,

"Cooper has a problem."

West asked for an air-clearing meeting between the players, the coach, and West. Riley, furious, refused. "You've put the coach's whole credibility in question," Riley exploded, according to friends who discussed the incident with Riley.

The confrontation sealed Riley's decision to leave the Lakers, but in truth he had other reasons to want out. He felt the players had lost their fire. "A seven A.M. practice before we won the championships would have been understood," he now says. "But not after four championships. . . . They changed. I never changed."

Another frustration was mounting within Riley. Because he had such great players, Hall of Fame-bound athletes who made the game seem effortless, he never felt he received the credit he deserved for inducing stars to sublimate their towering egos and play great defense, or for deftly transferring team leadership from Jabbar to Johnson. It was a running joke among sportswriters that Riley, who had the best winning percentage of any N.B.A. coach in history, did not win the Coach of the Year award until 1989-90—a year his team was eliminated from the play-offs.

The way Knick management figures it, they have a window of three years to win it all. Why? Because the team is built around its one superstar, Patrick Ewing, and they estimate he has perhaps three peak years left.

And even if the Knicks go farther than expected in the upcoming play-offs, they are three players away from a championship-caliber team, or so they think. The championship Knicks of 1970 and 1973 had five scorers, five athletes who could win a tight game in the closing seconds. The current Knicks are carrying three starters—Jackson, Wilkins, and Oakley—who through midseason were totaling a mere twentynine points per game. They had hoped to get one key addition in a swap before the February 20 trading deadline; they were able only to make the minor acquisition of backup center James Donaldson from the Dallas Mavericks.

"It's a Field of Dreams story" says Checketts about Riley and his father. "Pat didn't get a chance to say good-bye, or even hello."

There is another transformation Riley would like to pull off. "We need to change the nucleus and personality of this team," says an important member of the Knick family. The core Knick veterans—Jackson, Wilkins, Oakley, and Ewing—says someone who sits beside them on the bench and watches them closely, are not good friends. They don't pal around together. They simply don't seem to care about one another. They are not family, which is what Riley expects.

The Knick brain trust also worries about the New Yorkers who surround them at every game. The ticket holders in the Garden, along with the ones in Boston, are "the most sophisticated in the league," argues Marv Albert, the respected television voice of the Knicks. But the Celtics, unlike the Knicks, have rewarded their fans with a winning tradition, with players and teams that inspire awe. Bostonians come to their dingy Garden to root. New Yorkers, after twenty years of inflated prices and crushed hopes, are accustomed to screaming at their Knicks, not for them. They are knowledgeable and unforgiving, all too ready to call anyone who drops a pass or blows a lay-up a bum! "In other cities, the fans are all over the visiting team," says Knick V.P. John Cirillo. "In New York, they're all over you."

Last year, it dragged Patrick Ewing down, which is why Checketts believes that the star center's contract hassle may have been about more than money or pride. "Patrick didn't know if he wanted to face it anymore," Checketts thinks. Checketts concedes that Knick fans had reason to be angry with the team and past management, but the Utah-born executive feels fans in New York, unlike any city he can name, swing wildly between contempt and adulation. "One of our biggest issues is that many of our players don't want to play at home."

Of course, fan loyalty is always dependent on team performance. Will the Knicks be able to maintain the focus that has enabled them to overachieve so far? Will Checketts and Grunfeld be able to acquire the talent the Knicks need? If the team flames out in the play-offs, will Riley's four championship rings lose their hypnotic spell? When will the players begin to chafe under his Spartan code?

There is an irony behind the sniping that hounded Riley out of L.A. and is beginning to echo, however faintly, in Madison Square Garden. The grumbling is based on Pat Riley's style, not substance. It was the style, the intensity, that rubbed nerves raw in Los Angeles, not the substance of his brilliant record. Among the many reasons the Knick job is attractive to him is that it offers the opportunity to demonstrate that a good coach can transform an average team, that substance can prevail over style. Just because no one sees him sweating, Riley says, doesn't mean he's not.

What the fans and the players see is Mr. Cool. What they don't see is a son playing catch with his dad.

Only on rare occasions, like the New Year's Eve dinner with the Checkettses, or speaking about Magic Johnson and AIDS, does he open up. (Riley chokes up when he says he calls Johnson about twice a week "to touch base" and is awed by his friend's determination to just "go out and live life. The man is bom of special stuff.") In January, he suddenly described how he and Chris sobbed through Father of the Bride, the bittersweet Steve Martin comedy about a father who loses his daughter to marriage and misses his little girl. At times like these, Riley's emotions rise to the surface. But the next moment, there is about him, the way there was about his father, a seemingly impenetrable distance.

"The most important lesson that I took from my father is control," explains Pat Riley. "When I was a player I always hated coaches who lost control. My father just carried himself in a way that you always knew he was in control of his emotions. That's the way he was. A sense of self-control in any situation."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now