Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

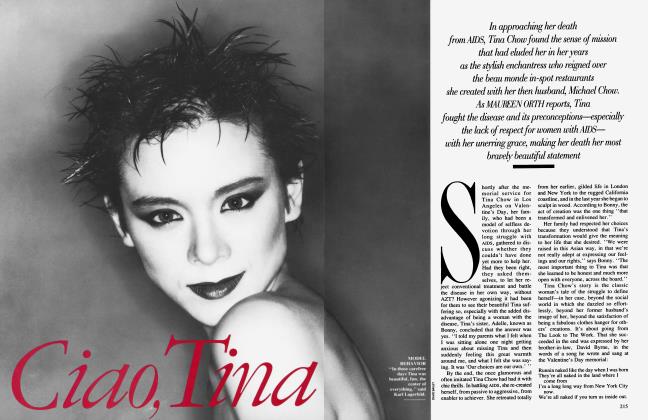

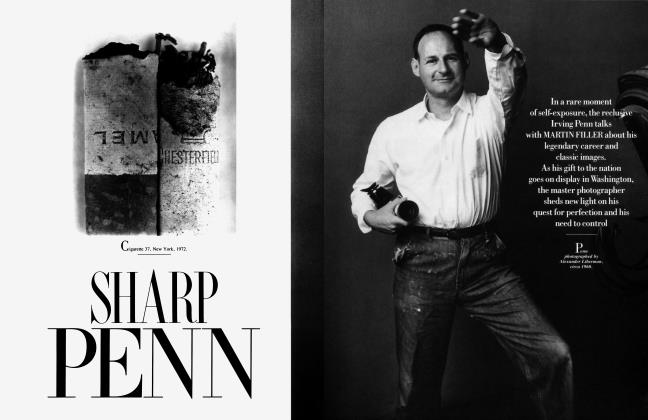

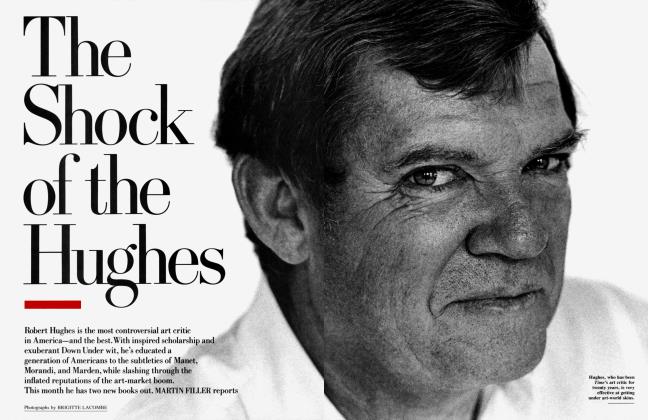

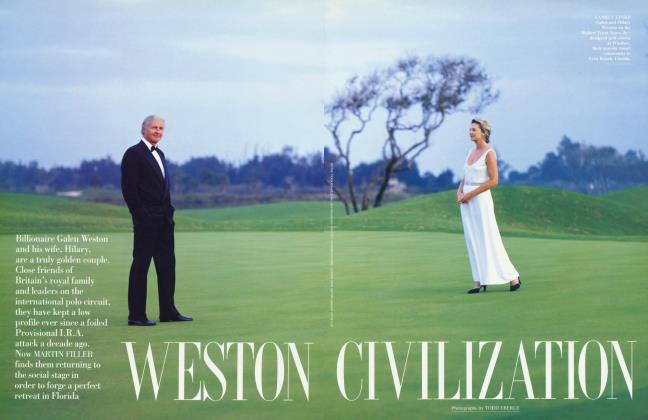

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMore than just old money, Paul Mellon epitomizes the old-school style of impeccable taste and discretion. So why, after a long life quietly devoted to aesthetic and philanthropic pursuits, has he chosen to reveal his most private doubts and anxieties? MARTIN FILLER reports, on the publication of Mellon's frank memoirs, Reflections in a Silver Spoon

A Cool Mellon

'I've been through so many different kinds of life in my life," says Paul Mellon over one of his lethal gin-and-vodka martinis before lunch in his Washington, D.C., house, "that it's hard to make an amalgam of them." It seems an odd confession from a very collected, suave old gentleman in this ravishing setting: a sunfilled library superbly decorated by his wife, Bunny, and hung with great paintings by Degas, Vuillard, Bonnard, and Braque. Wearing a seventeen-year-old black pin-striped suit from H. Huntsman & Sons (where he has had his clothes made since 1928), Paul Mellon, honorary knight commander of the Order of the British Empire, exudes the confidence of a man truly to the manner born.

But quite a different image —one riddled with self-doubt, undercut by insecurity, and marked by a long quest for personal awareness—emerges from his surprising autobiography, Reflections in a Silver Spoon: A Memoir, written with John Baskett and published this month by William Morrow. In fact, the very appearance of this probing private history is an unexpected event, in that the eighty-four-year-old philanthropist, art collector, and horseman has heretofore struggled to stay out of the public eye. And no wonder: twice in his early life major scandals swirled around Paul Mellon's family, deepening his innate reticence and leaving him with a distaste for exposure of any sort.

Unlike has-been movie queens and quick-buck instant celebrities, Mellon certainly does not need to write a tell-all autobiography for the money. He has been richer longer than any other living American. When Paul Mellon was a boy, his father, Andrew Mellon—one of the original robber barons of the Gilded Age—was among the three richest men in the United States, along with John D. Rockefeller Sr. and Henry Ford. Today, Paul Mellon's fortune is estimated at more than $800 million, yet he is legendary not for his extraordinary wealth but as the very epitome of taste and style that no amount of money alone can buy.

"The two great aristocrats of America in recent times have been Paul Mellon and Jock Whitney," says John Richardson, the art historian. "They both had great discrimination, great collections, great stables, were at home on both sides of the Atlantic, and kept their enormous philanthropy very quiet."

Indeed, Mellon is all the more esteemed at home and abroad for refusing to become part of international cafe society. Next to him, Gianni Agnelli seems a bit overeager, Heini Thyssen a tad showy, and Jacob Rothschild is just beginning to get the hang of it. Invitations to one of the Mellons' seven houses—the farm in Upperville, Virginia, the brick mansion off Washington's Embassy Row, the French-style town house off New York's Park Avenue, vacation places on Cape Cod, in Antigua, and one under construction on Nantucket, and a flat on the Avenue Foch in Paris—are as rare as they are coveted. ''The whole point about Bunny and Paul is that they're enormously private," says one New York socialite.

But as inaccessible as the Mellon style is to those who crave to see it, rest assured it is no myth. I. M. Pei, the architect, who has designed three buildings for Paul Mellon, is himself famous for his refinement and exacting standards. The Mellons' taste, he says, is "very understated, but it's there. The house in Upperville is very simple—the architecture, the interiors, great works of art on the walls. But it's nothing like Bill Paley's or Mrs. Astor's, nothing rich like that." Says another frequent guest when questioned about the Mellon style, ''It's an absolute and total dream. . . Bunny runs the houses beautifully. It's the best. Usually, it's a group of four or five [guests] at the most. And you're surrounded by smiling faces who want to do things for you. She's got people who have been there thirty years, and she's always seen that everything is perfect."

And it's a good thing, too. Paul MelIon is well aware of his "almost obsessive attention to detail." One friend of his wife and of her great friend, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, concurs: "Jackie's told me what a tough time Bunny has with him, keeping up all those houses, because he expects everything to be just so." But another close Mellon friend sees it otherwise: "He is very demanding, but it doesn't really come up, because that's the way Bunny would do it anyway. And he's not the monster Bill Paley was— Paul is not demanding half-open yellow rosebuds in Nassau at Christmas."

I felt I d never measure up to him, says Mellon of his father.

Mellon hos an almost obsessive attenton to detail. But he s not the monster Bill Paley was."

Mellon is quite the opposite of the typical tycoon. "He's the most unarrogant man that's ever been," says David, Duke of Beaufort, master of the Beaufort Hunt, which Mellon first rode with in the 1930s. "When he used to come hunting with us, he used to stay at a little pub and kept his horses with a farmer. English country people have no idea of rich Americans, and they just thought he was a nice gentleman. They didn't realize he was the richest man in the world.... He was very much liked because of his great humility, although being colossally rich." The Earl of Drogheda, Mellon's former son-inlaw, agrees. "He's always behaved in the way that the English upper classes like to think they behave," he says. "You can't say anything nasty about him. He was always extremely agreeable and without any sort of side."

That may be why Mellon has willingly exposed himself to what many would consider a harrowing process of self-examination. "I've been thinking about it for a long, long time," Mellon says of his book as a wood fire crackles behind him. ' 'I suppose one of my motives for doing it would be a latent feeling of growing up in the shadow of a great man. And I think that unconsciously I felt that.... So writing the autobiography may have been, in a way, a kind of justification."

Though that assessment is delivered in a patrician (Continued from page 196) accent that sounds English to most American ears, the telltale jargon of the confirmed analysand pops up everywhere in Paul Mellon's speech. Indeed, his extensive and enthusiastic experiences with psychotherapy are one of the most unexpected aspects of a life that otherwise seems anachronistically like that of an eighteenth-century country gentleman.

(Continued on page 230)

Nonetheless, it was no Whig diarist who inspired Mellon during this lengthy and sometimes painful project. "In both modes of analysis [the Freudian and the Jungian], I kept repeating a great deal of my life anyway," he recalls. "In a way, my analyst, Dr. Jenny Waelder-Hall, encouraged me to do the autobiography. I remember my talking to her about it in analysis and saying that I found it hard because I'd get bogged down in the details. And she always said, 'Well, don't do it that way. Do it just with vignettes, because those are the interesting things anyhow.' "

But as much of a departure as Mellon's interest in psychiatry may seem, it does not come as a great surprise, even in the unintrospective equestrian world. "It was obvious he was rather mixed up at one time," says the Duke of Beaufort. "He was so apologetic. He certainly had some worries about something. I couldn't quite make out what. . .but he'd sort of apologize for being there, practically."

One of the very few things Mellon admits he would have done differently in his life is to have seen a therapist at an earlier age. "I've always regretted that when I was at Yale I didn't know about the psychiatric part of the health department," Mellon now says. "It's too bad, because maybe if I'd been able as a sophomore or a junior to have had a little guidance, I might have felt much better much sooner. ' '

Nevertheless, Mellon's unusually selfeffacing nature, regardless of its psychic origins, has enabled him to get on with all kinds of people, something even the welladjusted rich cannot always manage with ease. He has been equally successful among horse grooms and museum curators, foundation functionaries and worldclass architects, army buddies and members of the British aristocracy. Above all, Paul Mellon is no snob, a fact that can be discerned by those who are able to spot one a mile off.

His contacts with the House of Windsor, unlike those of other millionaires who pursue the royal family for social advancement, have been grounded in mutual sporting interests. During her first state visit to the U.S., in 1957, Queen Elizabeth took a break from her official duties in Washington to have tea with the Mellons at their farm fifty-five miles west of the capital and look over their training track. Mellon has been invited to Kentucky for dinner several times during the Queen's visits, when she inspects new bloodstock for her stables, and he still plans his three or four trips a year to England "depending on what the horses are doing," which has often been quite a bit. In 1971 his horse Mill Reef won the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes at Ascot. The Queen Mother, for whom the race is named, made an impulsive visit to the winner's circle to tell the delighted owner, "I simply had to come whizzing down to congratulate you on that wonderful little horse." And last spring the Queen Mother and Mellon were given honorary degrees from the Royal Veterinary College of the University of London, presented to them by Princess Anne, the university chancellor.

On occasion, the Queen herself has sought Mellon's advice. As he tells it, "The Queen also trains with my trainer, Ian Balding. When I had Mill Reef, her former trainer, Peter Hastings-Bass, was very ill with cancer and had to get Ian, who was only twenty-five, to help him. I was asked to go to the Royal Box at Ascot for some of the races and for tea, and the Queen asked me whether Ian ought to keep on as head trainer or not. I said he should, and she said that was what she thought, too."

During the Prince and Princess of Wales's 1985 trip to Washington, the Mellons gave a Sunday lunch at Oak Spring, their Virginia house, with a guest list that included Caroline Kennedy, Charles Ryskamp (now director of New York's Frick Collection), and J. Carter Brown (director of the National Gallery of Art, who in January announced his retirement). Prince Charles came away raving about the art collection and library—including paintings by George Stubbs and illuminated books by William Blake—claiming it was the best-displayed collection he'd ever seen. "I'm glad to hear that," Mellon says with characteristic modesty. "He got along with Bunny very well, because he's interested in gardening and books and flowers. He's a very nice man."

Paul Mellon's love of horses and Bunny Mellon's love of horticulture—she is one of the most respected plantswomen in the U.S.—have cemented their friendship with America's equivalent of royalty, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. "She's a very good rider, very, very good," says Mellon. "She really loves it. She used to hunt with us quite a bit when the president was alive.

.. . She has two horses with us now, and a little house near Middleburg that she uses when she comes down to ride."

For more than thirty years Bunny Mellon has been one of Jackie's most devoted friends and her virtual court gardener. At President Kennedy's request, Bunny Mellon transformed the White House Rose Garden, next to the Oval Office, into a dazzling outdoor reception room befitting the chief executive. She was a munificent member of Jackie's White House restoration committee. After J.F.K.'s assassination, his widow asked Mrs. Mellon to arrange the flowers at the Capitol, St. Matthew's Cathedral, and Arlington National Cemetery, and to place a basket of flowers from the Rose Garden at his grave. And in 1968, Mrs. Mellon accompanied Mrs. Kennedy to Atlanta for Martin Luther King Jr.'s funeral. Interestingly, although a lifetime Republican, Paul Mellon has never been closer with a First Family than he was with the Democratic Kennedy s.

Bunny Mellon (who uses her full name, Rachel Lambert Mellon, only professionally) did much to soften the starkness of the John F. Kennedy Library's harborfront site in Boston. As the building's architect, I. M. Pei, recalls, "Bunny was asked by Jackie to come and look at it and said, 'Jack loved the dunes. We've got to bring some of the dunes here.' And we said, 'How can you bring the dunes there?' It was all muck, no sand, nothing there. . . . We were building on man-made land, and it's very difficult to make it look natural. 'No, no,' Bunny said. 'Never mind. We'll try.' And she brought her own men, and I tell you, in a matter of months it became a dune. But at what effort, my gosh! We had to plant the seedlings of the dune grass just like the way people transplant hair. That's the perfectionist in her."

Although as soft-spoken as her husband, Bunny Mellon is described by those who know her as far more prone to control. "She desperately needs her court and total fidelity," says one New York socialite. "Once she takes a shine to you, she's terribly, terribly nice and thoughtful and gives presents. But it's sort of cannibalistic. Unless you're careful, she'd like to buy you and have you as her personal liege man. You just have to get out at a certain point. "

That is a recourse that few of her close friends have taken, however. Her generosity is staggering: the loan of the couple's private jet; baubles by her favorite jeweler, the late Jean Schlumberger; furniture (a $17,000 bed for Jackie Onassis, according to Kitty Kelley's Jackie Oh!); and even suits (several a year from Huntsman for a British peer). Just before Christmas not long ago, Mrs. Mellon was seen going from her chauffeur-driven station wagon to the door of her New York house, wearing a tan raincoat and her signature boating cap with the brim turned down, laden with dozens of small blue shopping bags from Tiffany.

Her employees are no less subject to her attentions. "She tries to make slaves of craftsmen," says one New York antiques consultant. "There were these two boys who did everything for her. She wouldn't travel without them, and they were always set to work, putting fifteen coats of lacquer on the front door and then sanding them down until they finally got the exquisite darkness and smoothness of verte cypree and were then allowed to put fifteen coats of lacquer back on."

This, after all, is the woman who upon the retirement of her favorite designer, Balenciaga, was introduced by the old master to Hubert de Givenchy, to carry on her tradition of wearing haute couture. (Givenchy has since become one of her closest friends, and she has designed his gardens in France.) Though not a clotheshorse, she does care greatly about her looks for big events. "She wears her uniforms of skirts and sweaters," one good friend reports, "and then she'll have a breathtakingly lovely, very simple Givenchy ball dress with a great necklace for some occasion."

Although clearly devoted to each other, the Mellons pursue largely independent schedules, often using their twenty-twoyear-old Gulfstream II to jet around on short notice. "It has nice little Ben Nicholsons and things in it," says one frequent passenger. "And it's very simple: pale gray with navy tweed upholstery. They use it a great, great deal, you know, because there're so many houses." Even in Antigua, Mrs. Mellon's attention to detail never falters. The late decorator Billy Baldwin recalled "a slat house adjoining the dining room where she kept, along with her orchids and seedlings, three tree toads that serenaded us all evening long."

This is the second marriage for both Paul and Bunny Mellon, and each gives the other considerable latitude. Bunny Mellon is independently rich: her grandfather invented Listerine, still made by WarnerLambert pharmaceuticals. She remains on friendly terms with her first husband, Stacy Lloyd Jr., and has taken the Gulfstream to see him in St. Croix during the Mellons' sojourns in Antigua, where he has also been a guest. In fact, Lloyd was a friend of Paul Mellon's before Bunny left one for the other, and the lifelong connections within the Mellons' small circle are one reason it remains impervious to outsiders.

"To me, it's old home week," says one longtime friend who often stays with the Mellons. "What it is to me is the familiar thing, which I think applies to that whole world. There were three or four schools that we all went to and three or four colleges. And the sons were put into the brokerage firms and everybody knew everybody. It was a tiny, tiny world that went from Philadelphia to Boston, and all intermarried."

Paul Mellon's father was bom just outside that orbit, in western Pennsylvania, but he ranged much farther from it in his choice of a wife. Andrew Mellon was the son of Judge Thomas Mellon, an Ulster Presbyterian immigrant who left the judiciary in 1870 to found T. Mellon & Sons (the forerunner of the Mellon Bank), bedrock of the family fortune. Andrew Mellon was still unmarried at age forty-three, when he made a transatlantic crossing with one of his closest business partners, the coke baron and art collector Henry Clay Frick. It was on that fateful voyage that Mellon met Nora McMullen, the beautiful but spoiled youngest child and only daughter of a Hertfordshire beer baron, whose McMullen brews are still made there.

It was love at first sight for the dour businessman, but considerably less for the flighty nineteen-year-old. She rejected the marriage proposal of the fabulously rich American, but her father, a man of considerable ambitions—he rented Hertford Castle as his family home from the Marquess of Salisbury—apparently prevailed upon her to accept. It turned out to be a big mistake.

After their wedding reception on the grounds of Hertford Castle, the couple returned to Pittsburgh, seat of the Mellon millions but a factory town of appalling gloominess, much like the grim, businesslike personality of the tycoon himself. When she got the chance, Nora Mellon fled home to England. On a voyage back to the U.S. in 1902, she met a London layabout named Alfred Curphey, with whom she began an incredibly indiscreet ten-year affair financed with funds unknowingly supplied by the unsuspecting, cuckolded husband.

The Mellons had two children—Ailsa, bom in 1901, and Paul, bom in 1907— but Nora's maternal duties did little to deter her pursuit of romantic excitement. Glancing toward his mother's sepia photograph on a desk in his Washington library, Paul Mellon wistfully says, "I noticed several times when Mother left to go to England just before Christmas, or not being here on my birthday or Ailsa's birthday. It just seemed odd to me. You would have thought she'd stay for Christmas, regardless of what the situation was."

In 1904, Nora Mellon finally disclosed the liaison, and her startled husband paid Curphey to withdraw. The bounder cheerfully took Mellon's check, but the lovers resumed their romance surreptitiously not long afterward. During the interim, however, the Mellons reconciled long enough to conceive Paul, who was bom in Pittsburgh and christened at St. George's Chapel at Windsor Castle on his first trip to England, at the age of six months. (Mellon is convinced that that rare ceremony in the royal-family church presaged his lifelong Anglophilia. Indeed, at the time, his parents were renting Sunninghill Park, later intended as the home of the then Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip and on the site of the Duke and Duchess of York's new house.)

But soon after Paul's birth, relations between his parents began to unravel for good. Determined to have it all—lover, money, and children—Nora Mellon asked for a divorce and preyed on her husband's morbid fear of notoriety by threatening to go public with her distorted version of events. And she tried to disgrace him further: a medicine bottle was allegedly removed from Mellon's bathroom cabinet, and it was implied that he used it to treat a venereal disease.

Finally, Andrew Mellon ceased being a pushover. The marital strife was having obviously harmful effects on their impressionable children—Paul began to suffer from a variety of psychosomatic complaints. Mellon sprang into action at last and launched legal steps to prevent Nora from taking them back to England with her. The Mellon house in Pittsburgh, with "watchers" hired by both husband and wife to monitor each other's movements, came to resemble an armed camp. Eventually a court-appointed guardian took the children to live in another house to escape the tension, but that embarrassing move increased their shyness among their inquisitive friends.

Soon things quickly went from bad to worse. Hitting her husband where it hurt most, Nora told her side of the story in excruciatingly melodramatic detail to a Philadelphia paper and had copies distributed in Pittsburgh (where, she suspected, the powerful Mellon would be able to quash reports in the local press). He in turn used his political influence to change the state's divorce laws to his advantage, giving the court discretion to deny her a trial by jury, a move which backfired when Mellon was denounced for subverting his wife's right to due process. Then, all at once, it was over: a compromise was reached without a jury trial, and in 1912 the mismatched couple at last received their divorce, sharing custody of the children.

Well provided for in the settlement— she got about $1.25 million, then a fortune, though only a small percentage of Mellon's wealth—Nora Mellon soon parted from her British beau. She eventually remarried, but not before Andrew Mellon, amazingly, asked her to marry him again, in 1923, while he was secretary of the Treasury under President Warren G. Harding (a post he would retain under presidents Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover, becoming the third-longest-serving Treasury secretary in U.S. history). She sensibly declined, and lived on until 1974, just short of her ninety-fifth birthday.

Mellon betrays little rancor toward his mother, but little fondness either. The Mellon divorce scandal occurred at a time when even a quiet split ensured certain social death, and the emotional scars it left on the Mellon children lasted a lifetime. Paul Mellon believes the divorce made Ailsa (who married and then divorced the diplomat David Bruce) more withdrawn and led to her later reclusiveness and hypochondria. ("She was a poor little rich girl who aged badly," says a former art dealer who knew her from her days as a major collector of Impressionist paintings.) Paul Mellon clearly sided with his father emotionally; his last words on his mother are "We were friends, with a certain amount of affection between us, although I would not call it love."

He did, however, seek the love of his caring but remote father, and constantly believed himself unable to please the glacial old man—fifty-two years the boy's senior. "I felt I'd never measure up to him in the ways he would have liked me to measure up," Mellon now says with his characteristic candor. "And I think that was kind of a shadow that I was under for a long time."

There is no doubt that in his fashion Andrew Mellon loved his son: soon after Paul graduated from Yale, in 1929, the tycoon transferred enough stocks to make Paul rich in his own right. But he could not fathom some of Paul's greatest enthusiasms, often telling him, "Any damn fool knows that one horse can run faster than another."

After receiving his Yale degree, the young Mellon went on to read English history at Clare College, Cambridge, one of the happiest periods of his life. His half-English parentage made him aware of what to expect, unlike many of his countrymen. "I knew the English character enough to know that I wasn't going to be flooded with invitations and that people would be a little standoffish," he says, breaking into a smile that makes his face look uncannily like Ronald Reagan's. "And that didn't bother me at all. As it turned out, I found that it was perfectly easy to get along with the people I was closest to, like the people I rode with."

There were also nights danced away at London's fashionable Cafe de Paris, and a further plus came in 1932 when Andrew Mellon was named American ambassador to the Court of St. James's. But the inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt as president early in 1933 put an end to that English idyll. The Republican ambassador was replaced by a Democrat, and back in the U.S. another dark cloud descended over Andrew Mellon. In March 1934 he was accused of fraud on his 1931 incometax return, and the government announced it was seeking more than $3 million in back taxes and penalties.

"It was a very bad time for all of us," says Mellon as he looks up at the dashing 1924 Sir William Orpen oil portrait of his father over the library chimneypiece. "Mostly for my father," he adds slowly, "but there's also a certain stigma if it's a tax case."

Furthermore, Andrew Mellon was the most reviled man in America after Herbert Hoover during the Great Depression. As Paul Mellon now recalls, "I remember about 1930 driving back from Washington to Pittsburgh and I stopped at this garage. And on the wall there was a placard that said, HOOVER BLEW THE WHISTLE, MELLON RANG THE BELL, WALL STREET GAVE THE SIGNAL, AND THE COUNTRY WENT TO HELL. ' ' He pauses for a second to chuckle, and his collector's instinct surfaces. "I don't know why I didn't buy that from the man."

At the time, though, the taunt could not have seemed so amusing. Still, when the fraud charges were brought before a grand jury, it refused to return an indictment. As Mellon now notes, "It always surprised me that in the middle of the Depression a group of workers would have seen so clearly that there wasn't fraud. You would have thought for reasons of revenge that they would have sided with the government. It seemed to me that that was such a clear vindication of my father, and an indication that people knew unconsciously that it was a political move on Roosevelt's part. Nobody's ever been able to say that Roosevelt actually instigated it, but I can't imagine that [Secretary of the Treasury Henry] Morgenthau and the rest of them would have been so eager about it if Roosevelt hadn't been behind it."

Roosevelt biographer Arthur Schlesinger Jr. agrees only in that there is no proof of a vendetta. "Robert H. Jackson, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., and Homer Cummings were all men of honor," he wrote in reply to a request for a comment for this article, "nor do I know of any evidence that FDR had any personal animus toward Mellon." The civil case dragged on for several years and was resolved only after Mellon's death in 1937, when a final tax assessment of almost half a million dollars was levied by the government, but all fraud penalties were thrown out.

For a few years before and after his father died Paul Mellon made a halfhearted attempt to assume Andrew Mellon's role as the head of a diversified business empire, but that is the one world that has always bored him stiff. While still in his thirties he gave it all up—a high position in the Mellon Bank and directorships of family-controlled firms, including Carborundum, Gulf Oil, and Pittsburgh Coal—to pursue a life of gentlemanly pleasures he was sure his father would have frowned on.

In 1935 he married Mary Conover Brown, a Kansas City-bom divorcee, and together they discovered one of Mellon's abiding interests and the salvation of his personal happiness: psychiatry. Paul Mellon is now a very happy man, but that contentment has sometimes been misunderstood as the result of his great riches. The Duke of Beaufort remembers one night when Mellon was having dinner at the Duke's house in the country. "A friend of mine and his, Jeremy Tree, who's a horse trainer, was also there. Paul Mellon was sort of philosophizing"— here Beaufort slips into a nasal American twang—" 'Waal, in life I somehow think the bad things seem to equal out with the good.' And Jeremy said, 'Well, certainly have in your life, I must say.' "

But in fact that equanimity is the hallmark only of the postanalytic Paul Mellon. A year before they married, Paul and Mary read Carl Gustav Jung's Modern Man in Search of a Soul and were profoundly affected by it. She suffered from asthma and had read that there might be a psychological basis to the disorder, and she began seeing a Jungian analyst in New York. In 1939 the couple traveled to Switzerland, where they were treated, individually, by the great man himself at his house in Kiisnacht, near Zurich. The experience was not a success—Mellon found Jung's method maddeningly imprecise and irrelevant to his particular problems—and the outbreak of World War II provided a convenient excuse to return home.

Mellon fared much better with Freudian therapists in the U.S., even though Mary Mellon's difficult personality and erratic behavior seemed not to have been helped by psychiatry. Neither was her asthma, and she died suddenly of an attack that came on while she and her husband were riding in Virginia in 1946.

Two years later he married Bunny Lloyd, and their children—Timothy Mellon (now in the railroad business), Catherine Mellon Conover (who preceded Elizabeth Taylor as the wife of Senator John Warner), Stacy Lloyd III (formerly a Washington rare-book dealer), and Eliza Lloyd Moore (a painter and ex-wife of the current Earl of Drogheda, the Architectural Digest photographer known professionally as Derry Moore)—melded seamlessly into one family unit.

Among the passions Paul and Bunny Mellon pursued together was art. Although Paul Mellon had grown up in a house hung with his father's Cuyps and Corots, his own early collecting was confined to English sporting pictures, albeit of a very high order. In 1936 he bought his first painting by George Stubbs, the greatest animal painter of all, decades before Stubbs was given his proper due by serious critics. ("I thought even then that Stubbs was a pretty good artist," says Mellon with quiet pride.)

Bunny Mellon played a decisive role in expanding her husband's taste. "Another thing that I think she must be given credit for," says an old friend of the couple, "is that she's the one who opened his eyes to all the wonderful things that are now in the National Gallery." There are quite a few of them in their various houses as well. On the wall of their Washington living room is a small Renoir oil sketch of an artichoke, one of their first joint acquisitions, made on Bunny Mellon's initiative.

Working together and never buying a piece unless they were in agreement about it, the Mellons steadily amassed a collection of French Impressionists distinguished for its exceptional quality and unusual sophistication, especially when gauged against the obviousness and redundancy of so much Impressionist art. Over the chimney piece of the Washington living room hangs Paul Cezanne's spectacular Boy in a Red Waistcoat, bought in 1958 at the watershed Jacob Goldschmidt sale at Sotheby's in London for $617,500, at the time the world record for a painting at auction. It was won for Mellon by an overeager bidding agent who went well over the limit his client had set. ("I'm very lucky that he did," Mellon says with justifiable satisfaction. Last year, Mellon promised the picture to the National Gallery in honor of its fiftieth anniversary.)

On another wall is Edgar Degas's The Dance Lesson, a long, narrow canvas of great poignance and subtlety. "Outside of my first Stubbs, I think that's my favorite picture of the whole collection," Mellon says, unable to take his eyes off it. "It's the combination of colors, this girl with that touch of red down in that comer, and the light coming in the windows, and the delicacy of the skirts. ... He was really a great painter. ' '

The pleasure that Mellon gets from his pictures is as high as the quality of the works themselves, which make the muchvaunted Annenberg collection of Impressionists look for the most part like garish greeting cards. For unlike the elder Mellon, Paul has bought pictures for his personal enjoyment rather than as a civic duty.

Andrew Mellon spent his declining years methodically setting up one of the most splendid acts of generosity his country has ever seen: the endowment and construction of the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Mellon stocked that building with extraordinary treasures bought at very high prices, even during the depths of the Depression, including masterpieces by Van Eyck, Raphael, Titian, and Rubens taken from the Hermitage by Stalin to finance his faltering Five-Year Plan and sold through the Knoedler & Co. gallery. Mellon was also the mainstay of the cunning Lord Duveen, who rented an apartment below Mellon's Washington flat and stocked it with prime pieces to tempt the old Maecenas at his leisure.

Paul Mellon maintains the allegation that the project was a trade-off with the government to drop his father's tax case is a myth: the elder Mellon began thinking about the transfer of his private collection and a new building to house it in 1927, well before his troubles with the government began. If anything, it seems remarkable that Andrew Mellon proceeded with his scheme through what he felt was a trumped-up prosecution.

But his sense of public responsibility never wavered, and neither has his son's. Frank E. Richardson is a New York private investor and horseman who grew up near the Mellon family in the Pittsburgh region and has hunted frequently with Paul Mellon, whom he considers the beau ideal of the American gentleman. "In western Pennsylvania there is a strong Presbyterian tradition of having to return to society the good that you've received from it," explains Richardson. "It's just the way we were brought up, and you didn't question it. So it's kind of a shock to realize that it now seems so unusual and that Paul is singled out for doing what used to be expected of everyone. But I suppose that with the exception of the Rockefellers he's one of the very few left who does so much so quietly."

It was Andrew Mellon's idea to leave his name off the National Gallery of Art, and that gift set the low-key style for Mellon philanthropy ever after. Only on rare occasions has Paul Mellon departed from that parental example. "People have said to me, 'Why did you not let Yale put your name on the British-art building?' " he relates. "Well, my answer is that when you walk in the door there's a plaque that says it was given by Paul Mellon, class of '29. And it's known. But there are other reasons not to have your name on it for the future. I'd be much less likely to give money to the Hirshhom Museum, for instance, than I would to something that isn't named. In my father's day, it was perfectly clear to him that the Wideners weren't going to give their collections to the Mellon Museum, even though it was in Washington."

Although Paul Mellon did not shrink from paying top dollar for the best Impressionist pictures in the fifties, even he felt priced out of the market in due course. Explains the Duke of Beaufort, chairman of Marlborough Fine Art in London: "He bought them for nothing, and then I remember when they got expensive he just couldn't believe it. He said, 'I don't know, they expect me to keep buying these damn pictures, but I wouldn't dream of paying these prices.' "

Instead, Paul Mellon returned to his first love in art to build his second great collection, British painting of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. He started in 1959, at a time when the British School was low in price and plentiful on the London market. But instead of the conventional works favored by American tycoons of his father's generation—grand fulllength portraits by Thomas Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds, or saccharine pictures of children by George Romney, John Hoppner, and Sir Thomas Lawrence—Paul Mellon concentrated on a far different vision of England.

According to Allen Staley, a professor of art history at Columbia University and a noted authority on British painting, "His taste really reflected a countryhouse, almost a Country Life, kind of world: Stubbs, Arthur Devis, conversation pieces of a gather informal nature. The real significance of his collection, even more than the Stubbses, might be the revaluing of the rather modest, unpretentious, smallish picture. Everything grows out from that view of an eighteenth-century rustic sporting world, the kind of life Mr. Mellon would lead either in England or Virginia. He has certainly legitimized huge areas of British art that were dismissed before."

With the help of Basil Taylor, a brilliant but unstable British art adviser who committed suicide in 1975, Mellon built the best survey outside London, and in 1966 decided to give it to Yale, along with a gallery and study center to house it. Louis Kahn, now widely considered the most important American architect since Frank Lloyd Wright, was chosen to design the museum. Like many clients, Mellon found the otherworldly Kahn more than a bit bizarre. "One morning when we had breakfast," Mellon recollects, "he seemed a little crazy. He was drawing these things all over the tablecloth. He was sort of mystical in some way, but he was fascinating."

Kahn, however, had a more pompous idea of Mellon and his intentions than Mellon himself did—a problem that has been experienced by many who expect a grand seigneur rather than a gentleman farmer. Thus, at the bottom of an early proposal, Kahn inscribed the legend "Palazzo Melloni," even though the patron's own conception was not a Florentine palace but an English country house. Today an oasis in the decaying and dangerous heart of New Haven, the Yale Center for British Art manages to seem a beautifully run private establishment, especially when its founder comes to pay a call, as he did one morning last December, flying up in the Gulfstream to see a definitive retrospective of the work of Richard Parkes Bonington, a short-lived nineteenth-century prodigy little known outside art-historical circles.

Mellon's reactions to the works on display are personal but well informed. It takes him well over an hour to work his way slowly and attentively through the show. Stopping before Bonington's most admired pictures—small, brightly colored views of Venice—the major lender to the show is unafraid of expressing a heretical opinion. "I like these Venetian scenes less than any of them. They look like postcards to me."

If the British-art center comes closest to capturing Mellon's private personality, then his most public benefaction is sure to remain the East Building of the National Gallery. Between the beginning of the project in 1970 and the opening in 1978, the costs skyrocketed far above original estimates and wound up at $94.4 million, making it one of the most expensive cultural buildings of the period. But, as I. M. Pei recalls, Mellon was concerned mainly that everything be done right, even as the outlays mounted. "It's really a question of judgment and standards, and it's not always the same," notes Pei. "But when you put the two together, and you have very excellent judgment and very high standards, usually the decision is right."

With the precipitous rise in art prices during the decade after the East Building was completed, Mellon eventually found himself to be what he calls "art-poor"— the contemporary equivalent of being landpoor, or having too much of one's assets in a not easily liquefiable commodity. Thus, to the astonishment of many in the art world, Christie's announced that fourteen works from Mellon's private collection would be put up for auction late in 1989. Although it had long been believed that his pictures were earmarked in their entirety for museum bequests, Mellon decided to sell for "estate-planning purposes"—that is, to cash in at the peak of the market rather than risk a sale after his death, when prices might not be so high.

"It was kind of like a shark frenzy, people paying these tremendous prices," says Mellon of that unprecedented run-up of the international art market. "As time went on and people could still take deductions on capital gains, more and more people began to take advantage of that, just like people began to think more and more of works of art as investments. I think it was a growing feeling of greed, all part of this growing balloon of inflation in things to do with art.

"I was just hoping it would hold up," recalls Mellon of his gamble. "I had lunch at Christie's just before with Lord Carrington. I said to him, 'How long do you think this Impressionist market is going to hold up?' And he went like this," says Mellon, holding up crossed fingers.

As it turned out, that wish for luck was only halfway fulfilled. Seven of the fourteen Mellon works did not meet their reserve prices and were not sold, including Picasso's Death of Harlequin (a subject deemed too difficult for the Japanese market) and three Degas wax sculptures (believed to have conservation problems), on which Mellon had pinned high hopes. The other seven pieces, however, sold very well indeed, fetching a total of more than $51 million.

Mellon's biggest winner was Edouard Manet's The Rue Mosnier with Flags. He had paid $317,000 for the canvas at the Goldschmidt sale in 1958. It sold to the J. Paul Getty Museum for $26.4 million. "Well, I didn't do too badly," Mellon admits, and even manages to be grateful that he still has his beloved Degas waxes. "I'm awfully glad they didn't sell."

Still, there are many of his peers who are never satisfied, no matter how much they make or how much they achieve, so Paul Mellon's contented outlook can be seen as his greatest fortune beyond his vast material advantages. "Oh sure," he says, responding to the inevitable question, "I often think of things I would have done differently. But then I think, Well, how do I know? That might not have turned out that way at all.... I feel that everything that happened to me and everything I did was a logical sequence from other things before it. I don't have any big regrets about anything."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now