Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

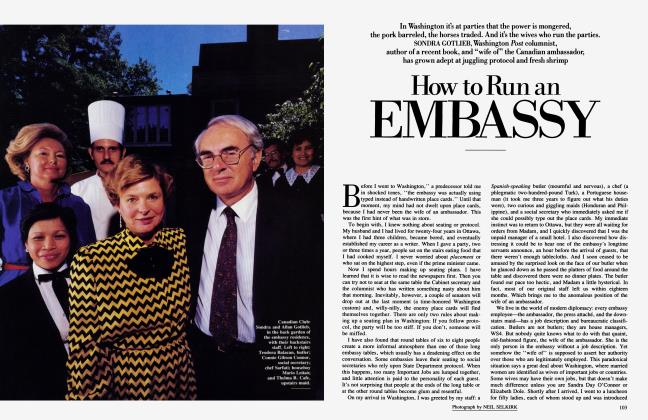

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhile many people, including me, admire David Stockman for his honesty and his commitment to efficient government, neither virtue is as unalloyed as it may seem. After all, Stockman’s fame —the fame that brought him a $2 million advance from Harper & Row for his soon-to-be-published memoirs—is based largely on that legendary 1981 interview with William Greider in The Atlantic, in which Stockman essentially admitted to having participated in a fraud on the voters. That’s honesty of a sort, I guess. As for efficient government, when the thirty-four-year-old congressman from western Michigan was appointed director of the Office of Management and Budget in 1980, he came on like Benihana of Tokyo, knives flashing. Chop, chop, chop. Yet by the time Stockman left office last summer to write his book and become an overpaid investment banker, the federal government was losing more than three times as much money every year as when he got the job.

So, whence the cult of Stockman? Unless Harper & Row has made a giant miscalculation—as many envious Washingtonians secretly hope—this rather austere figure must have an impressive following outside Washington, many of whom will be willing to shell out some absurd amount like $24.95 for his book. Economists like to talk about people “casting their dollar ballots.” Measured in these terms—which are, after all, in keeping with the true spirit of the Reagan era—Stockman is more popular than any elected politician apart from the president himself, whose life story went for a reported $3 million.

Ironically, the failure of Reaganomics to achieve a painlessly balanced budget—a failure that isn’t really Stockman’s fault—is partly responsible for Stockman’s prominence. How many budget directors can you name from the era of mere double-digit billion-dollar deficits? Whatever may happen to the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings balanced-budget law, during the next few years this country will be obsessed with fiscal bookkeeping. We are entering the era of the green eyeshade, and David Stockman is a hero for our time.

Shortly after President Reagan hired Stockman, “Svetlana,” the Washington Post astrologer, expressed alarm about the young O.M.B. director’s lack of “earth signs.” She wrote, “People whose charts are void of earth elements may talk a lot about practicality... but sooner or later they do something that stuns people around them with its impracticably.” Svetlana was right on the money. Even as she wrote, Stockman was breakfasting regularly with Bill Greider at the Hay-Adams Hotel, spilling the beans.

After Reagan and a few aides, I may have been the person most dismayed when Greider’s article appeared the following December. I had just started work as editor of Harper’s, and all of a sudden the name of our archrival, The Atlantic, was on everyone’s lips (for what may have been the first time in several centuries). Even more upsetting, I had had an advance copy of that issue of The Atlantic for nearly a week before the story broke (professional courtesy) and had thought, Humph. Nothing new here.

I may have been naive about how Washington works, but I was, in a way, right. The essence of Stockman’s confession to Greider was that he knew perfectly well that you can’t cut taxes, go on a defense-spending spree, and balance the budget at the same time—that the administration’s plans would lead to enormous deficits. Of course he knew it. Everyone knew it. What’s more, no one had any doubt that everyone in the administration knew it, too. Well, maybe not everyone, but certainly everyone except the Chief. Every great con man believes his own con, as a wise man I know likes to say.

However, Washington abides by the convention that certain people are not supposed to say what everyone knows. It suits the interests of politicians, because it allows them to lie unmolested. And it suits the interests of journalists, whose role as interpreters and analysts would be sadly devalued if politicians took to saying what they really thought. When this convention is violated, it’s called a “gaffe.” A gaffe consists of a politician telling the truth. Now, that’s news. So when Stockman admitted to knowing what everyone knew he knew, he earned his place in the record books of gaffology.

What becomes front-page news isn’t always new. Stockman had made virtually the same confession to Alexander Cockbum and James Ridgeway of the Village Voice before he even took office. But he wasn’t a major figure then, and nobody paid any attention. Stockman was asked, “How about paying for all the defense, with the tax cut and balancing the budget.” He answered, “At the rhetorical level, you’ve got to defend it artfully. At the policy level it doesn’t matter.” I.e., you lie. You promise that “a surge in economic activity will more than adequately finance the defense increases,” while consoling yourself privately that “larger deficits ...are not that bothersome.” A year later, the world was shocked to learn that David Stockman didn’t think Reaganomics would balance the budget.

Why does Stockman keep blurting out the truth in such an impolitic way? In part, it’s because he suffers from an affliction, rare in Washington, known as compulsive honesty. Even after being taken on “a visit to the woodshed,” as Stockman described his dressing-down by President Reagan after the Atlantic article, he continued to emit smaller geysers of gaffery. His last official gaffe was an outburst at a congressional hearing, where he said that the American military establishment sometimes seems concerned more with protecting its retirement benefits than with protecting the security of the United States. Very true, of course.

Shortly before he quit, Stockman came to lunch at The New Republic, where I now work. He was not the ‘‘thin, almost spectral” figure described by George Will in 1979. Indeed, he was a bit pudgy. He chain-smoked cigarettes and told the truth for two hours. Since the session was off the record, none of his truths flowered into gaffes. But it was a remarkable display of a public official attempting to control his rogue mouth, and failing, the same way Peter Sellers, as the title character in the movie Dr. Strangelove, attempts and fails to control his independent-minded arm. We would ask him about the latest economic fantasy uttered by the president. He would smile, refuse to comment, take a nervous puff on his cigarette, and then comment. We’d ask about this or that government program or tax loophole ardently defended by Republicans on Capitol Hill. ‘‘Oh, that.” Pause. “You’re not going to get me to talk about that." Longer pause. Twitch. “Well, everyone knows it’s just a boondoggle for the rich.”

But compulsive honesty probably isn’t the only explanation for the way Stockman slipped into a close symbiotic relationship with an important Washington Post editor like Bill Greider. For a man generally thought of as an ascetic policy nerd—“a zealot with numbers,” as the late Joseph Kraft called him— David Stockman has an impressive record of currying favor with people who might be, and usually are, useful to him.

When Stockman was appointed to O.M.B., a news analysis in the Washington Post described him as “the Republican mirror-image of Ralph Nader.” Clever, but not quite right. Yes, he’s that smart. Yes, he’s that committed to his own clear worldview. Yes, he’s that formidable an adversary. Yes, he may well buy his suits from the same tailor. And yes, he’s got that same half-mad glint of intensity. But Stockman harbors a large quantity of the germ that Nader is miraculously free of: personal ambition. It’s sort of a relief, when you think about it.

Stockman followed a path to early success that is now known, in business self-help manuals, by the vulgar term “mentoring.” This is the vertical version of “networking.” It means meeting and cultivating established people who can be given a vested interest in your further progress. It can take the form of serial monogamy or of playing the field. It can be done crudely or with some grace. Stockman has been exceptionally fortunate (charitable interpretation) or skillful (uncharitable interpretation) in finding mentors. While still in graduate school at Harvard, he was taken up by Daniel Patrick Moynihan. While an obscure congressional aide, he came to the attention of Meg Greenfield of the Washington Post. Other Stockman mentors have included the Post’s David Broder, columnist George Will, and Congressman John Anderson.

Stockman also has undergone his share of timely transformations, and not just political ones, either. In his two terms as a congressman, he hung out with the Republican young punk crowd—the “popcons” (populist conservatives). During this period, his published writings took on a more strident, snarling tone, and his byline changed from David A. Stockman to plain “Dave”—just like “Jack” Kemp, “Newt” Gingrich, “Vin” Weber, and the rest of the boys.

But Stockman—he will be “David” again on the cover of his book—is a classier act than that. Although he is widely regarded, with some justification, as a conservative, his kind of thinking could be the salvation of liberalism. It will take a Stockman to clean up the Augean stable if there is ever again going to be either the money or the public support for necessary new government programs.

Stockman’s influential 1975 article in The Public Interest, “The Social Pork Barrel,” coined a phrase that did more damage to the liberal cause than any other until 1984, when Republican political guru Kevin Phillips used the term “reactionary liberalism.” But “The Social Pork Barrel” wasn’t an attack on the concept of activist government. It was an attack on the corruption of that concept by politicians of both parties. Too much of what the government spends money on, Stockman argued, has little to do with helping the needy or any other coherent public purpose. “What may have been the bright promise of the Great Society has been transformed into a flabby hodge-podge” that serves only to help get politicians re-elected by spreading money around as widely as possible.

“We are interested in curtailing weak claims rather than weak clients,” Stockman told Bill Greider, meaning that he wanted to cut off worthless programs, not powerless people. “We have to show that we are willing to attack powerful clients with weak claims.” This is precisely what the Reagan administration has failed to do, and the result has been fiscal disaster. The relatively modest aid that goes to the genuinely needy has been squeezed, but the vast government programs and tax loopholes for the middle class and the rich have remained virtually untouched. How this happened is the great story Stockman will have to tell in his book if it is to be worthy of all the hoopla.

Fortunately, the ambitious Dave Stockman and the compulsively honest David Stockman needn’t be at war over this one. The more tales he tells out of school, the more money he’ll make.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now