Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

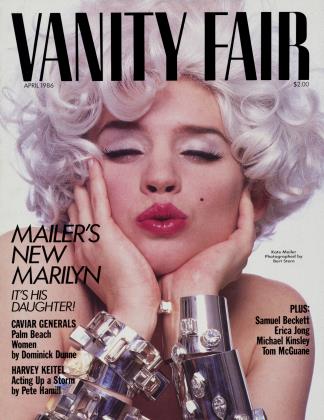

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMine is the baby-boom generation: raised to be Doris Day, we came into our twenties wanting to be Gloria Steinem, and now we are rearing our late-life daughters in the Age of Princess Di and Nancy Reagan. Could we possibly be heir to greater confusion in the realm of sex roles? Not bloody likely. We have seen models of femininity turned upside down, not once but twice in our not very long lifetimes. In our teens we apologized to the chauvinists for wanting to be overachievers in society (when, by their lights, we were supposed to long for nothing but wifedom and motherhood). In our twenties and thirties, having become overachievers, we apologized to the radical feminists for still wanting to wear come-fuck-me pumps, silk underwear, and makeup; for liking men; for wanting to have babies (when, by their lights, we were supposed to join lesbian communes, wear work denims and Earth shoes).

And in our forties we suffered the final indignity of being told that feminism was obsolete by a generation of women who never knew what it was like to graduate Phi Beta Kappa from an Ivy League college and be asked on one’s first job interview, “Can you type?”

Never mind. Every woman comes to understand feminism someday. If it doesn’t happen when she graduates summa cum laude from Radcliffe and is sent straight to the typing pool; if it doesn’t happen when a graduate-school adviser asks her, as one asked me, “But why should a pretty girl like you want a Ph.D. in eighteenth-century English literature?”; if it doesn’t happen with her first divorce, when the husband she has been supporting asks her for alimony, the house, and the furniture; then it certainly happens with her second divorce, when the husband she has been supporting demands alimony, the house, the furniture, and custody of the kids. Sooner or later, it happens. Sooner or later even the best and the brightest young women figure out that this is still, alas (insert huge desolate sigh), a man’s world.

Usually the turning point comes with the first baby. Men and women can be equal in the workplace (in some few professions), equal in the kitchen, equal in the bedroom; but when babies come along, the jig is up. Biology rears its ugly head. You can believe in equality from now till doomsday, but your breasts leak milk when the baby cries, and his don’t. This changes just about everything. The unique bonding between mother and baby—written in the DNA, passed down through eons of primate and human evolution—determines that the mother’s concern for the infant will have a different intensity from the father’s, and that society will exploit this intensity for its own (usually chauvinistic) ends.

Whether this exploitation is conscious or unconscious on the part of most men is not the point. There are good, vulnerable, caring men who didn’t make this exploitative system what it is and who might, if they could, remold it closer to the heart’s desire. That is irrelevant. We are not analyzing men when we analyze sexism; we are analyzing a system that came into being for a variety of biological, political, and economic reasons and that is carried along by many individuals—some of whom recognize how faulty and in need of change it is, but most of whom have neither the vision nor the power to change it.

The second wave of feminism (in the late sixties and early seventies) produced a tidal wave of literary analysis of patriarchal attitudes. It seemed to change the very climate of opinion. Certainly we endured a media orgy about women’s rights, women’s wrongs, women’s books, women’s health, women’s diseases, women’s sanity, women’s insanity, and so on. People (even women) got sick of hearing so much about women, and a backlash set in. And when the dust settled, what did we find? Women had infiltrated certain professions where they were previously not welcome. In publishing, in advertising, in television, some became visible and highly paid. But they failed to reach the very top in corporate, financial, and political arenas—and even in those professions they successfully infiltrated, childbearing became their Waterloo, separating the girls from the women the moment it became apparent that the world could be lost for lack of a competent nanny and that the workplace did not take kindly to milk stains on the silk blouse or the canceling of meetings because of sick children.

The trouble with the second wave of the feminist movement in America was that it did not address itself to the 90 percent of women who had, or wanted to have, babies. To them it seemed an elitist movement of childless women writers (or women who had seemingly forgotten that their children had ever been young) which dealt with every issue of women’s liberation except how to be liberated while raising happy, healthy, cherished children. Betty Friedan pointed out years ago that so long as the women’s movement focused on lesbian rights and did not address itself to the longings of most women for warm, affective relationships with men and children it was doomed to alienate its enormous potential constituency. And alienate them it did. In some cases it alienated them right into the arms of Phyllis Schlafly and the right-to-lifers.

Having stumped across this country on book tours for the past decade or so, I can bear witness to the fact that the women of America are ready for liberation, ready for sexual freedom, ready to embrace their own strengths and believe in their own powers—but they are most emphatically not ready for a movement which puts down the most meaningful relationship in their lives: their relationship with their children. Nor are they ready to give up sleeping with men in the name of some abstract principle that won’t keep them warm in bed at night. If only the second wave of the feminist movement had not concentrated on such admittedly worthy issues as lesbian rights and E.R.A. at the expense of the pragmatic problems of working mothers, it might not have alienated the millions of women who were ripe for the picking. The issue that would have united women instead of dividing them— the issue that might have built a cohesive nonpolitical feminist movement, a coalition of left and right, of men and women—was the issue of liberated families, liberated child rearing: how to be a mother, in short, without getting screwed.

A Lesser Life: The Myth of Women's Liberation in America, by Sylvia Ann Hewlett, which Morrow published last month, is the sort of book that could start a revolution. It could stoke up the still-smoldering coals of a women’s movement that has gone cold in the last few years for lack of young leadership and new focus. The problems, goddess knows, are there. But it will take a new angle of vision and new leadership to get the movement going again. The last decade of feminism has shown us that “no-fault” divorce favors men and hideously penalizes women and children. The last decade of feminism has not brought equal pay for most women, or adequate child support for most children, or any of the social programs (whether publicly or privately funded) that would make it possible to work productively and raise happy children at the same time. Who bears the brunt of this? Women and children. Their condition in the United States is far worse than in other, comparable industrialized countries.

Sylvia Ann Hewlett is an economist and mother who has written a trenchant, well-researched economic analysis of women in America that could become the Feminine Mystique or the Female Eunuch of the eighties. More than that, it could serve as blueprint for a new era of feminist activism that would focus on children and their needs—a focus long overdue in this country.

Hewlett’s analysis is fascinating (and likely to be taken more seriously in our bottom-line-oriented society than a literary or personal analysis) because it is essentially an economist’s analysis. It speaks in terms of statistics, and the statistics are both unassailable and astounding.

In 1939, for example, when F.D.R. was president and Gone with the Wind won the Academy Award for Best Picture, American women earned sixty-three cents on the dollar for every dollar earned by men. Fifty years later, after a flood of feminist books, a decade of feminist consciousness-raising, and a massive entry of women into the marketplace, American women earn sixty-four cents on the dollar earned by men. And that’s not all. Our wage gap has remained nearly constant while that of other Western industrial nations has appreciably narrowed (often by more than 10 percent), especially in the last decade. Britain (even under Thatcher’s conservative government), Italy, Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands have all closed up the wage gap far more successfully than we have.

In the area of pregnancy leave, the United States is a disaster compared with these other countries (again, even Britain under Thatcher). Not only are our federal laws and many of our state laws silent about giving a mother or father a period of time to care for a new baby, but employers still routinely fire women if they take even a short leave to have a baby. Nor does federal law require employers to provide disability-insurance benefits to pregnant women. Our national attitude is pretty much that if women “choose” to have children, they can pretty much take the consequences alone. There is no sense of children as a societal imperative, a societal treasure. Rather, we tend to treat them as luxury consumables, “options”—like that cellular phone in your new Jaguar. If you “choose” to have them and work, you’d better be rich, nanny-equipped, and silent about the complications they present in your working life.

This state of affairs is in stark contrast to other Western industrial countries, where pregnancy leave is the rule and not the exception, where health insurance for pregnancy is provided on a national level, where there seems to be a general understanding that children are not expensive hobbies (like polo ponies), but a legitimate national priority.

America has the highest divorce rate in the Western world and the fewest societal supports for mothers and children. “During the Reagan years, 3 million more children and 4 million more women have slithered into poverty,” says Hewlett. The private sector doesn’t want to deal with the problem, and neither does the public sector. Not only is America “the only advanced country that [doesn’t] completely underwrite the medical costs of childbirth,” but it is also “the only industrialized country that has no statutory maternity leave.” As Hewlett points out: “One hundred and seventeen countries (including every industrial nation and many developing countries) guarantee a woman the following rights: leave from employment for childbirth, job protection while she is on leave, and the provision of a cash benefit to replace all or most of her earnings.” But not “child-centered” America.

Hewlett has cleverly compared America not only with Sweden (where women earn 81 percent of what men earn and have generous maternity leaves) but also with conservative Britain and Catholic France and Italy (where the last decade of feminism has brought great advances for women). The overall picture amazes and enrages. Suddenly, the personal becomes political. Hewlett understands that the immense difficulties of being an American superwoman and “having it all” are not one’s own personal failures, but have a clear economic base.

She analyzes the ways our economic system impacts on women and how and why the second wave of the feminist movement failed to redress these wrongs. Feminism in America, in both its first and its second waves, focused on equal rights rather than on the indisputable reality that motherhood is at the center of the lives of 90 percent of women. Anna-Greta Leijon, the Swedish minister of labor, says: “If children cannot receive good care while their parents are away working, the right to work becomes illusory for most women.” American feminism has been not only indifferent to the problems of mothers but downright hostile to children and childbearing. The focus has been on reproductive freedom, on women’s having career paths identical to those of men—despite the fact that women can have such career paths only if they choose never to have children. Though it is true that some women opt for childlessness, most don’t: for the majority of women, children remain enormously important.

I am sure that many feminists will attack Hewlett’s book for stressing the failure of the second wave of the feminist movement to grapple with the central fact of motherhood in women’s lives. It will be said that she overstates the case, that she is a Schlafly sympathizer (she makes a fascinating and provocative case for the defeat of the E.R.A. as a boon to women), that she is not a “good sister,” a good feminist, and so on. This is as predictable as it is sad. One of the worst aspects of being an American feminist in the last decade and a half has been the gloomy experience of being attacked from both sides, the chauvinists and the feminists. One can deal emotionally with being attacked by chauvinists (one can even exult in it as proof of commitment), but being attacked by fellow feminists is altogether another matter.

One of my own bitterest memories of being an American-style superwoman feminist trying to have it all goes back to the fall of 1978, when my daughter was just four months old. Throughout my very happy pregnancy I worked energetically, touring the country for the paperback of How to Save Your Own Life and writing my historical novel, Fanny. After Molly was born (by cesarean, despite a typically unrealistic preparation for “natural” childbirth), I breast-fed her and finished Fanny. I had a succession of impossible nurses and nannies, but somehow, despite my exhaustion and household troubles, the sheer exuberance of having produced a beautiful redheaded daughter while writing a picaresque novel about a beautiful redheaded heroine carried me through the weeks of sleeplessness and disruption that follow a baby’s entry into the world. Then I met my first emotional Waterloo.

I had been invited to read my poems at a women’s poetry festival at the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco, and though I had not done any public speaking since Molly was born, I felt that this was the perfect time to come out into the world again.

During my pregnancy I had composed a sequence of poems about the experience (the poems later went into Ordinary Miracles, 1983), and I thought the poetry festival would be an appropriate place to share them. My then husband and I flew across the country with four-month-old Molly in a denim baby carrier, left the baby and nurse at my in-laws’ house in Los Angeles, then flew up to San Francisco. This was the first time I had left Molly overnight since her birth, and she was still breast-feeding a couple of times a day. I knew that leaving her for forty-eight hours might end my dwindling supply of milk (Molly was a big baby who had started supplementary bottles at five weeks or so), but I felt it was important not only to my future but to my daughter’s for me to get out there and show—to myself above all—that having babies in no way impeded a woman’s ability to write (and publicly read) poems.

Imagine my dismay when I was virtually booed off the stage by a feminist audience of the lesbian-separatist variety for reading a series of poems that celebrated pregnancy and birth while affirming a woman’s strength and power. The poems in no way idealized pregnancy, but you couldn’t prove it by an audience of women in rebellion against fifties notions of happy motherhood. To say anything positive about motherhood was to push every one of their emotional buttons. I left the stage devastated and confused. Clearly, I had been expected to toe the feminist party line, which in that atmosphere was feverishly anti-male and anti-nuclear-family, and I had dared to celebrate motherhood instead.

This experience plunged me into one of the deepest depressions of my life (and did, by the way, end my career as a nursing mother). Never had I felt so betrayed by my own sex, or so fervently wished I had stayed home with the baby. It is unpleasant but predictable to be put down by male chauvinists, but when feminists attack at such a vulnerable time as new motherhood, the experience is devastating.

Hewlett underwent a similar experience at Barnard College (my beloved alma mater), and I am sure our experiences could be augmented by every American career woman who has ever worked and had babies simultaneously. There is no doubt in my mind that American feminism has had, historically, a strongly anti-child bias. True, we have seen babies on the cover of Ms. True, such feminists as Letty Pogrebin, Adrienne Rich, Robin Morgan, Phyllis Chesler, Betty Friedan, and Germaine Greer have written passionately about children. But there is no denying that the overall thrust of the movement in America has been to stress equal rights for both sexes as if men’s lives and women’s lives were identical. As Hewlett shows, most comparable European countries have succeeded in helping working mothers to a far greater degree because they have stressed women’s very different needs for additional support systems during their childbearing years rather than the abstract concept of equal rights. Even as distinguished a feminist as Eleanor Roosevelt was against the E.R.A. because she felt, as Hewlett does, that it would hurt women more than it would help them.

Women can function successfully as male clones in the workplace only if they never have children, and to demand this of most women is to thwart their deepest biological need—or to ensure that if they do have children, many of them will be forever doomed to poverty and emotional exhaustion. When I consider the difficulties of having and rearing one child, in privileged circumstances, with household help and financial freedom, I marvel at the passion and heroism of the millions of American women who raise several children sans money, sans flextime, sans nannies, sans anything that constitutes real support. No one witnessing this passion of women for their children can doubt the fact that a movement which looks away from the central fact of most women’s lives—maternity—will never win grass-roots support.

What, then, can be done to rekindle American feminism and remold it?

Hewlett outlines a plan of action developed by a family-policy panel she organized, which includes the following steps:

1. Pay equity for both sexes

2. Maternity and parental leave

3. Maternal- and child-health programs

4. Flexible work schedules

5. Preschool and early-childhood education

6. Public-sector initiatives for child care

7. Private-sector initiatives for child care

She shows clearly how these steps, if properly implemented, would save money in the long run and produce a better-educated, healthier population and a far healthier political climate. She is not proposing abstract principles for the sake of some abstract goal of equality, but practical reforms which would make the United States a stronger country and benefit both sexes economically.

Why, then, is she pessimistic about the prospect for any of these advances? Because historically American feminism has stressed equal rights above all reforms, and because a variety of cultural forces—the fifties cult of momism, the hostility of trade unions to women workers, the old conservative dream of the Norman Rockwell family with breadwinner daddy and housewife mommy—remain so strong in the minds of our politicians, policymakers, and populace even decades after they ceased to reflect the reality of most people’s lives. Above all, Hewlett makes it clear that children’s liberation must be the next great societal undertaking in the country if America’s economy is to survive. I wonder whether her book will be heeded as the intelligent warning it is, or whether we will continue to dream the old conservative dream while our children suffer the consequences.

For years I have longed for a revitalized women’s movement that would unite both sexes and fuse both ends of the political spectrum around the issues of children’s welfare and mothers’ economic sanity. Everyone knows that our present government wants to protect fetuses but starve children, protect wombs but penalize women, but nobody knows quite what to do about it. A Lesser Life presents a concrete vision of a revitalized feminism that puts children squarely at the head of all other national priorities. Is America ready for this vision? I hope so.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now