Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

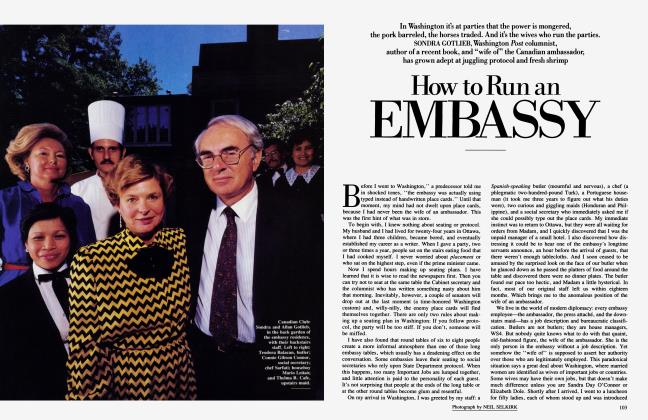

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOne Lodge, two Cabots, three Loebs, four Rockefellers...

The sands have been shifting this year over at the elegant Park Avenue mansion that houses the Council on Foreign Relations, a mysterious, hybrid organization—part think tank, part club—whose membership includes the secretary of state, the secretary of defense, the Federal Reserve chairman, the director of the C.I.A., and two former U.S. presidents.

First, David Rockefeller stepped down as chairman, and Pete Peterson, who used to run Lehman Brothers, took his place. Then council president Winston Lord was appointed ambassador to China, and the C.F.R. mandarins began searching for his successor.

The foreign-policy establishment speculated, the press speculated. Would it be former undersecretary of state Lawrence Eagleburger? Foreign Affairs editor William Hyland? Or maybe dark horse Peter Tarnoff, head of the World Affairs Council, a West Coast version of the C.F.R.?

The dark horse had the lead when “Bud” McFarlane was liberated from the National Security Council and became a late entry in the presidential sweepstakes. Kissinger was reportedly backing McFarlane, while Tarnoff was the choice of his old mentor, Cy Vance. As usual, the media played up the tension between the Kissinger and Vance factions; as usual, the board members played it down.

The outcome made the front page of the New York Times: Peter Tarnoff, forty-eight, takes over this month as president of the Council on Foreign Relations. Tarnoff is a former foreign-service officer—and a Democrat—whose chiseled features have C.F.R. secretaries aflutter. The council he will run has the basic underpinnings of think-tankness—a solid membership of respected academics and foreign-policy professionals, resident scholars, annual fellowships, study groups, research projects. It also has cachet.

At a “meeting” (councilspeak for a speech, question-and-answer period, and reception or meal) for Paul Volcker, you’re likely to find many Wall Street heavyweights. When Shimon Peres comes to speak, a sizable chunk of New York’s media establishment will ascend the marble staircase to the recently christened David Rockefeller Room, traipsing back down again for a post-speech dinner of haute-Wasp food on the main floor.

Some of the notables who came by last year to chat (off the record, of course, which is half the fun): Bishop Tutu, George Shultz, Daniel Ortega, Prince Saud Al-Faisal, Helmut Schmidt, Valery Giscard d’Estaing, Lord Carrington, Robert McNamara, Claire Sterling, Carl Sagan. The council membership is equally eclectic. Belying its reputation as a liberal enclave (in some circles, in fact, the C.F.R. is viewed as part of a Communist Conspiracy), the council has attracted some of the country’s most prominent and rabid conservatives, old and neo: Norman Podhoretz and Midge Decter, the threelegged R. Emmett Tyrrell, Richard Perle, George Will, Michael Novak, and Jeane Kirkpatrick.

How does one become a member? Well, it’s not the Vertical Club; getting through the doors of the stately Pratt House requires credentials, connections, and U.S. citizenship. Women, minorities, and successful young things have an edge, as does anyone living outside the Bos-Wash corridor. Like Ivy League schools, the C.F.R. is increasingly big on “diversity.”

You may get in if you have put in a number of years at the State Department, on the National Security Council, or in the C.I.A., and have written for the council’s Foreign Affairs magazine. You might also try for a full professorship at Harvard, though this is no sure bet—the council has “waitlisted” a number of top academics. You could become a media personality. Or you could sign up as top executive with a bank that has lost a lot of money in Latin America (this guarantees your interest in the international debt crisis).

Then you need to find a proposer and as many other council members as you can to write letters testifying to your probity, interest in international relations, experience in the field, etc. Once you’ve been proposed, that’s that. You won’t be interviewed or inspected; your file will remain “active” until the eleven-member membership committee recommends you and the board of directors votes you in—or until you die, whichever happens first.

Of course, there is one thing that’s more snob than getting into an exclusive club: getting in, then letting your membership lapse. John Kenneth Galbraith did it, and has been insisting ever since that the council was a crashing bore. Richard Nixon, it’s said, simply stopped paying his dues. Perhaps the original antiestablishmentarian found the Council on Foreign Relations to be just a little too “in.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now