Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNijinska’s High Jinks

Stepping out of her brothers shadow

DANCE

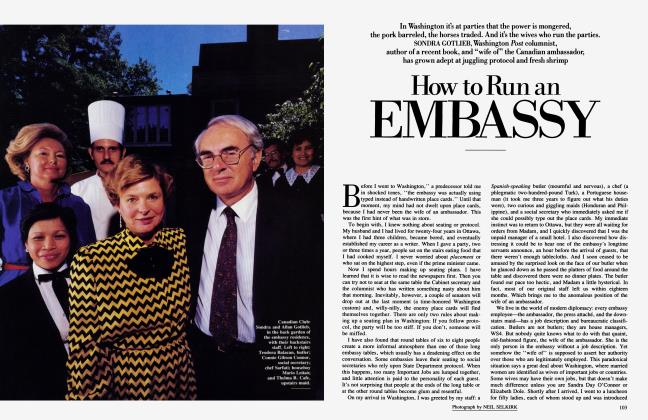

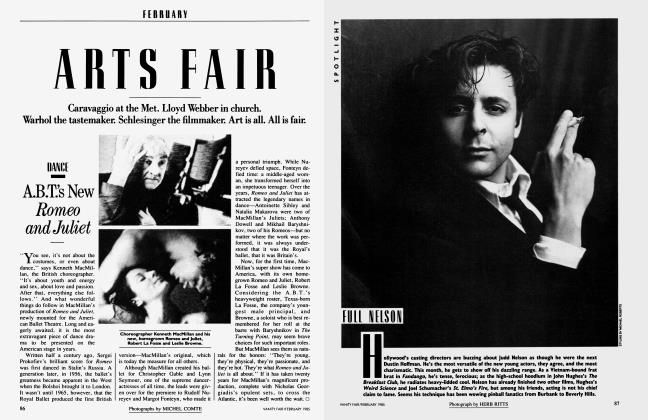

Serge Diaghilev called her “La Nijinska.” Igor Stravinsky considered her “fully the equal” of her brother Vaslav Nijinsky, the Baryshnikov of La Belle Epoque. But by 1917 Nijinsky’s triumphs and scandals— L’Apres-midi d’un Faune, Le Sacre du Printemps—were behind him; his crackup had begun. After le dieu de la danse took a grand jete off the deep end, his sister, Bronislava Nijinska, stepped forward to play her part in Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. A dancer and choreographer, like her brother, Nijinska never shared his fame (or his madness). Until recently she was known only to die-hard balletomanes, but with “La Nijinska: A Dancer’s Legacy,” currently on view at New York’s Cooper-Hewitt Museum (and traveling to San Francisco and Houston), her reputation should emerge from her brother’s shadow. When Nijinska wasn’t creating, she was cataloguing her creativity. Much of this show is drawn from her own collection of set and costume de-

signs, posters, and photographs.

Bom in a trunk in 1891, Nijinska took her first steps before an audience at age three; by the time she died, in 1972, her lengthy career had led her from Saint Petersburg’s Maryinsky Theatre to the Hollywood Bowl in a Proustian parade of famous names. As Diaghilev’s sole choreographer from 1921 to 1925, she was steeped in the samovar of the Ballets Russes, where dance, music, and design were brewed in equal measure. She worked there with Braque, Gris, Ernst, Miro, Stravinsky, Auric, Milhaud, Poulenc, and Cocteau—far headier collaborations than one sees today.

Getting her way was not always easy. While choreographing Stravinsky’s Les Noces, Nijinska locked horns with Diaghilev, as well as with the maestro and designer Nathalie Gontcharova; their vision of a festive peasant wedding was not the ballet she saw in the music. It took a year for Diaghilev to come around, but in the end Nijinska had her masterpiece: a

stark, somber ballet in which the exchange of nuptial vows resonates of ancient sacrifice. She had words with Jean Cocteau while fleshing out his scenario for Le Train Bleu (outfitted by Coco Chanel), but kept Francis Poulenc in stitches with the witty choreography she fashioned for his Les Biches. In her dances she seized the lean lines of classicism and fractured them. She took a swipe at ballet’s verticality and brought dancers to their knees again and again.

If her colleagues were at times difficult, Nijinska could be too. According to Alexandra Danilova, one of Diaghilev’s (and later Balanchine’s) great primas, “She was a little eccentric, as we say in Russia. Once she came wearing white gloves and I said, ‘Madam, is there something wrong with your hands?’ and she said, ‘No, but I hate to touch perspiring bodies.’ ” Igor Youskevitch remembers that “as a choreographer she was a terror; as a person she was the most charming woman I ever met.”

Diaghilev finally proved to be too resistant to Nijinska’s sexless, abstract compositions. She left the Ballets Russes in 1925 to launch her own globe-trotting career, but continued to collaborate with the likes of composer Maurice Ravel and Russian constructivist designer Alexandra Exter, staging ballets and operas for dozens of companies, including her own.

When Nijinska settled in California in 1939, she had already witnessed, and contributed to, the big bang in ballet history. Maria Tallchief, who studied with her there, says, “It was because of her that I decided to become a ballerina. Nijinska was the personification of ballet.” A Nijinska boom is under way—in recent years the Oakland Ballet, the Dance Theatre of Harlem, and Eliot Feld have all mounted revivals of her work. So once again,

Nijinska—the woman Sir Frederick Ashton has called “a genius, one of the very few”—is back center stage.

Thomas Connors

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now