Sign In to Your Account

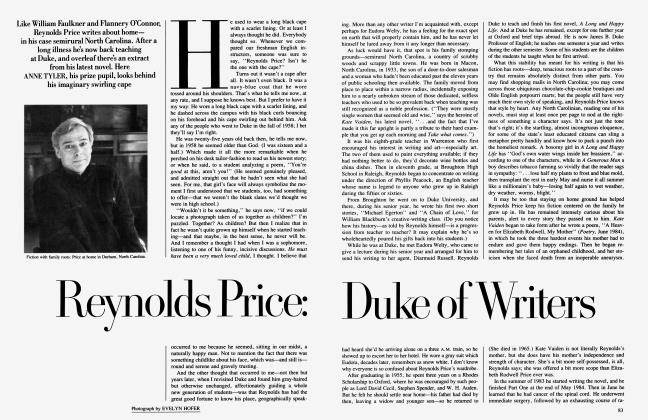

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

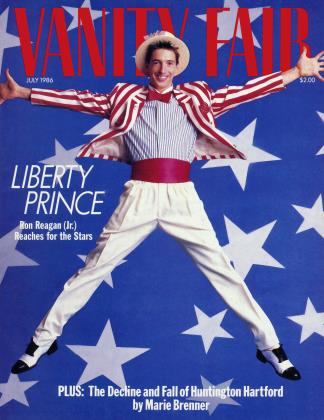

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRosario's Revolution

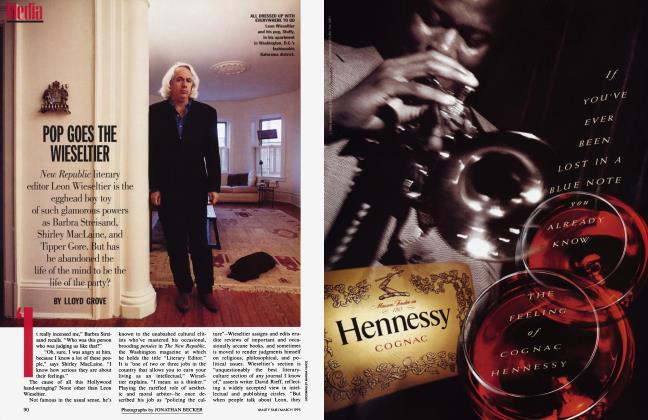

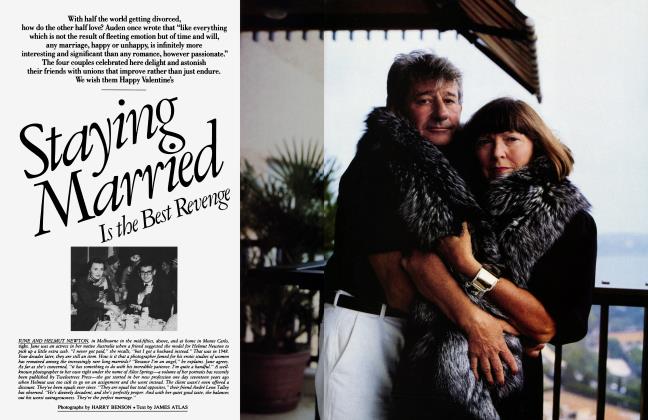

Rosario Murillo, the First Lady of the Republic of Nicaragua, has the jet-black hair, exotically lashed eyes, and cherried lips of a fortune-teller—and the lithe body of a strict vegetarian who performs a nightly regimen out of a Swedish exercise book. She projects a quality— Americans call it charisma, Nicaraguans angel or duende— that is less apparent in her sullen-faced husband ("a dictator in designer glasses," according to Nancy Reagan's husband). Her charm is the charm of a revolution peopled by the young, the brave, and the good-looking, a revolution that will be a scant seven years old this month.

At home, Murillo is a woman of power and influence; abroad, an eloquent and even glamorous champion of the Sandinista regime.

"A very good communicator," says Miguel D'Escoto, Nicaragua's foreign minister. "I tend to be much more abstract. Rosario adds a human dimension."

"A beautiful, tender, extraordinary woman—and committed to the revolution," says Hollywood denizen Joan Keller Selznick, who has given dinner parties for the Nicaraguan First Lady and various influential friends.

"A skilled propagandist," asserts a spokesman for the Reagan administration. "She knows the line and she says it in English. Just like Gorbachev, she puts a good face on for the public."

On her increasingly frequent forays into enemy territory, i.e., the United States, the common-law wife of Nicaraguan president Daniel Ortega, Comandante of the Revolution, has conferred with Jane Fonda in the West and Yoko Ono in the East; held forth in an interview with the Washington Post; made TV appearances with David Hartman and Phil Donahue; even managed to discuss peace with Nancy Reagan. On her own turf, Murillo has been an enthusiastic tour guide to a steady stream of visiting literati, movie stars, pop singers, producers, and other molders of American mass consciousness.

Thus she has deployed herself as a not-so-secret weapon in the war of words—and bullets—over the true identity of Nicaragua: Is it, as Ronald Reagan has claimed, the harbinger of "a sea of Red, eventually lapping at our own borders"? Or, as Rosario Murillo would have it, a poor, put-upon country trying to find itself? "This is an experiment," she says of today's Nicaragua. "What makes it so amazing is that it is possible in Nicaragua for Marxists and Christians to live together and work together for the same ideas, the same goals. And this is what Sandinismo is all about."

Rosario Murillo is the First Lady of revolutionary Nicaragua. The common-law wife of Sandinista supremo Daniel Ortega (who came to power seven years ago this month), Rosario is halfway between La Pasionaria and Bianca Jagger.

LLOYD GROVE

Her nation being one of the hemisphere's poorest, she has received no little attention for a $3,500 purchase of designer glasses for her family—and for her own chic garb. But, Murillo protests, she borrows most of her outfits from friends, particularly from one New York woman ("I'm not going to tell you who; I'm sure she wouldn't like it") who's "just a little bit slimmer."

"Some people want to gossip about this and that. Who worries about what Nancy Reagan is wearing? Who worries?" As for Gucci glasses, Murillo says, "I had no idea how much a pair of glasses could cost. I had never been shopping in New York before."

Her English is an enticing blend of European inflections and Latin rhythms. Her voice is rich and supple—equally expressive when delivering a speech, soothing a child, sharing a confidence, dressing down a subordinate, or chatting up a famous writer.

At January's PEN Congress in New York, Murillo, in silk brocade, was trailed by a blonde assistant and two brown-suited bodyguards to a celebrity-dense reception at Gracie Mansion. One of the mayor's men came up to console her over "silly stories" about the glasses, and offered to smooth her way to the shops. She smiled, and her assistant took his number. Later, she could be heard in conversation with Norman Mailer over the pop-pop-popping of cameras.

MAILER (between sips of white wine): We're a rich country.. .People with a lot of money are always very guilty, very paranoid... Communism's a real threat to them because it affects them religiously.

MURILLO: But who says we have a Communist society in Nicaragua?

MAILER: The secret fear of every capitalist is: What if God is a Communist?

MURILLO (laughing): Well, anyway, I do hope you can come to Nicaragua sometime. You will be my very special guest.

MAILER: Well, meeting you makes it easier to go to Nicaragua, I'll tell you.

'I'm her father, nothing more. I'm a man of seventy years. I have suffered a lot. My memory is very bad. I have no opinion of her. None at all!"

Then, with a bang of his telephone, Teodulo Murillo terminates the conversation, leaving a residue of confusion between one's ears. One might have bet real money that Don Teodulo would be delighted with his daughter's success in the world. But in the Republic of Nicaragua—while there may be regular shortages of laundry soap, cooking oil, light bulbs, even bathwater—confusion is a commodity in generous supply.

When the Sandinistas came to power in July 1979, Don Teodulo was a man of means. "Close media alta" was how people in Managua described the Murillos—only "upper middle" because, in the unforgiving calculus of Nicaraguan society, they lacked the cachet of the aristocratic Chamorros, the hugely rich Pellases, or even the brutal Somozas, who had ruled the country for half a century as their private preserve. Indeed, they were mestizos, of peasant stock. But Don Teodulo was a wealthy farmer and landlord, and the proud father of four very charming and accomplished daughters.

He would often say that the eldest, Rosario, was his favorite. While Don Teodulo and his late wife sent all their girls to Teresiano, one of Managua's most exclusive schools, Rosario was picked to be educated in Europe for four years—a rare privilege even among the city's elite. At eleven, she was sent to a Franciscan convent school in Devon, England, and then to a Swiss finishing school favored by upper-crust British girls.

When she returned to Nicaragua, Don Teodulo's favorite daughter was much transformed. She was fluent in French and English, intimate with Balzac and Dickens, and sophisticated beyond the small-town sensibilities of her father's Managua. She was also a little wild: married at fifteen, she was a mother at sixteen. By age twenty-five, with her first husband dead and a second marriage behind her, she forswore all others to set up housekeeping with Daniel Ortega, a bank robber-revolutionary who spent seven years in Somoza's prisons. With two kids and a reputation for being—in the argot of the seventies—"a free spirit," Murillo soon became Comandante Ortega's aide-de-camp in exile. It was inevitable, perhaps, that father and daughter would not always see eye to eye.

Nearly seven years after "the Triumph," as the Sandinistas call their ascension, Don Teodulo lives in a battered-looking Spanish-colonial house in a weed-choked neighborhood. Margarita Simpson, his second wife and the First Lady's stepmother, comes to the door. Unlocking the heavy iron grate that protects the entrance, she leads the way to a shadowy room and indicates a plain wooden chair.

"We have our ideas, Rosario has hers," she says with a thin smile. "She's very busy, of course—" Suddenly a big bearded man in an undershirt and Bermuda shorts storms into the room.

"Why are you talking to her?" he demands, and Margarita 1 Simpson flinches. It is Don Teodulo. He is shouting. "I'm her father—not her!" He comes closer, snorting, his dark eyes bulging. "I want to tell you something: I have no relations with my daughter! NONE WHATSOEVER!" He pounds a massive fist into a meaty palm. "Do you understand me? And I want to tell you something else! I'M NOT A COMMUNIST! UNDERSTAND?"

And then, just as suddenly, he storms out.

As Margarita Simpson leads the way to the door—for it seems just now like a good time to leave—she explains that Don Teodulo has been seething in this Lear-like fury ever since his daughter's associates started confiscating his land.

"The Sandinistas took a lot," the First Lady's stepmother says. She mentions a large hacienda known as El Trapiche, once the seat of Don Teodulo's kingdom, now a resort for the citizens of the New Nicaragua.

'He was terrible! He was very rich. But he was very mean. He wouldn't give us money to buy anything. At Teresiano I felt so ashamed all the time, not having the money I needed to spend on things, to show off in front of the rest of the girls."

Rosario Murillo is laughing—ruefully, it seems. If she is estranged from her aging father, she's no worse off than countless other Nicaraguans whose blood ties were severed by the civil war. The country is a hothouse of passions: fierce antagonists are likely as not to be nephew and uncle, sister and brother—sometimes daughter and father.

Much of Rosario s power derives from her husband. "A single hair on a certain part of a woman," goes the old Nicaraguan adage, "pulls more than a team of oxen "

She explains that pursuant to certain revolutionary policies of agrarian reform, the one-hundred-plus acres of El Trapiche, which boasts a natural spring, were turned into a spa for the people. Also built on the property was a secluded weekend retreat for the people's leaders, set off from the public area by a high gate and sentries toting Russianmade AK-47s.

"My father thought he was not going to lose it, because I was his daughter, you know—that I was going to speak out and say, 'You shouldn't be taking this away from my father.' But I could never do that. And that's one thing he can't forgive.''

Don Teodulo had mounted a desperate campaign to change his daughter's mind. "Well of course you can be a revolutionary now," she remembers him scoffing. "I was the one who paid for your education and made you a revolutionary." In the end, when it was clear she would do nothing, he repeated an old saying with the force of a bitter curse: "There isn't a pestilence that will last a hundred years, nor a people that will endure it."

"He was referring, of course," she says with a tolerant smile, "to the revolution as a pestilence, and the Nicaraguan people as a people who would one day overthrow the revolution."

Murillo is presiding over lunch at the First Family's residence, which from the dining room seems to stretch toward horizons of sun-washed patios and crimson tiles. It is bustling with the offspring of various marriages and liaisons—the eldest, eighteen-year-old Zoilamerica, named after Murillo's late mother; the youngest, one-year-old Maurice, named after Grenada's late prime minister.

They are looked after by three or four companeras, i.e., comrades, a term applying with equal utility to the household help, a government minister, a lover, a boss, a busboy, a member of the state security police, even a visiting journalist. The First Lady is referred to as la companera, though nearly everyone calls her Rosario.

Before the Triumph, Rosario says, the house and its art collection belonged to a banker (she doesn't call him companero). "He owed a lot of money to the government," she explains.

The next day, shopping in nearby Masaya with her clean-scrubbed brood of boys (Rosario a vision in yellow Ralph Lauren shirt, aqua stirrup pants, and soft gray demiboots, a jeep full of security men trailing), she is similarly ready with an explanation after encountering a peasant woman selling handicrafts from a hutch. The woman lives there with her own two sons, who are naked and filthy.

"We can't stand there and feel sorry for people," Rosario reasons, producing a compact from her purse to adjust her blush, "because that isn't revolutionary and that would absolutely not be dignified. Because it's not only that woman with her naked children, it's a lot of people in Nicaragua who have to get a higher standard in their living. So obviously you can't compare the house where this woman lives"—this with an air of resignation—"to the house where I have to live at this moment."

Ortega, her housemate, is very little in evidence. There's not much call in Nicaragua for joint appearances, "First Lady" being a nebulous variable in the equation of public life. One morning, when the austere comandante turns up in his redoubtable fatigues to bless the revolutionary faithful at a small public event, a visitor asks him about Rosario and he cracks one of his rare smiles. Then, enigmatically, he chuckles before turning away. Although Rosario has urged her companero to be more communicative, a promised interview never occurs.

In the tight little circles of gossipmad Managua, where the tangled love lives of the Sandinista elite is a favorite topic of discussion, presidential philandering is also a matter for speculation. "It's like Peyton Place," says Arturo Cruz Jr., an ex-revolutionary now living in the United States. But the evidence suggests that Ortega's union with Rosario hasn't lacked for passion. Indeed, before they met, they wrote each other poetry—he from his prison cell. And, while Ortega had one child by a previous companera, he has fathered five with Rosario.

There is certainly no doubt that she has influence with her husband. She is credited with Ortega's increasing sophistication in the public arena, up to and including his oratory (much smoother now than seven years ago) and apparel (he generally leaves home without the fatigues). And it is equally clear that much of her power derives from him. "A single hair on a certain part of a woman," goes the old Nicaraguan adage, "pulls more than a team of oxen."

For Rosario Murillo is not only the nation's First Lady and mother of eight. She is also the secretary-general of the Sandinista Association of Cultural Workers; editor of Ventana (Window), the Saturday cultural supplement to Barricada (Barricade), the official party newspaper; and a delegate to the National Assembly as well as the elite Sandinista party assembly.

And she is a published poet in a country that treats its poets as national heroes. Her latest book, courtesy of the state publishing house, is strategically displayed at two of Managua's most widely trafficked locations, the airport and the Intercontinental Hotel. It competes in the marketplace of ideas with a Soviet volume, Materialismo Dialectico, The Green Book of Muammar el-Qaddafi, The Speeches of Fidel Castro, volume two—but also, lest anyone be insufficiently confused, back issues of Self, Ultra, and Town & Country, this last graced by a cover story on "Mrs. W. L. Van Alen, Jr.: The Style of Patrician Philadelphia."

"We make the revolution when we write a poem," begins one of Rosario's recent verses, "or sing the love of Diana Ross / the eyes of Bette Davis / and the sighs of Barbara Streissand [sic]. ' '

In conversation, she often assumes The Poetic Disposition. "The revolution is like a poem," she says during one such reverie. "You change a word, you look for an adjective, you look for the proper expression. We're revising it every day. And in the process of writing this epic, many goals can be achieved and many successes can be attained, but also many mistakes can be made. But this is our poem."

Managua evokes nothing so much as The Waste Land.

Shortly after midnight on December 23, 1972, an earthquake all but wiped it off the map, killing tens of thousands of people in a shower of debris. In a twist of Latin-American surrealism, the eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes was holed up in the Intercontinental Hotel when disaster struck. He made his escape by private jet, presumably in his bathrobe.

The city was never rebuilt. Today it hugs the shore of Lake Managua like a bag lady in repose, wearing a frayed overcoat of revolutionary graffiti—SANDINO LIVES! DEATH TO THE YANKEE!— relieved by the occasional outdoor mural. One of the more impressive mixes muscular socialist realism and ersatz Picasso. It shows Spanish conquistadors visiting mayhem on the Indians; a scythe-swinging Grim Reaper swathed in a robe of Stars and Stripes; the hated Somozas; the beloved Sandinistas; the humble masses; the fierce battles; the unfurling flags; and finally various hunklike companeros in communion with their hacksaws and hammers. The procession of images fades greenly into Edenic paradise.

Home to a million people, a third of the country's population, Managua is overwhelmed by dust and weeds and mangled earth—a capital made up out of stray pieces of this and that. Blazoned monumentally on a high green hill, the initials FSLN (for the Sandinista National Liberation Front) dominate the vista like Nicaragua's answer to the HOLLYWOOD sign. Equally eye-catching are ubiquitous billboards for the nation's indigenous opticians. Bespectacled faces gaze down on the major highways, recalling the Old Testament proverb: "Where there is no vision, the people perish."

Babies can be heard squalling inside the hulks of long-abandoned office buildings; the pasty-bumt smell of tortillas wafts from the ruins of the old cathedral. Piles of garbage blaze all over the city, filling up the sky with billows of black smoke. Lot's wife must have looked back on such a scene.

But Rosario's domain, the Sandinista Association of Cultural Workers, resembles the paradise in the mural. In 1982 she arranged for the expropriation of a Somoza-era nightclub, along with part of a public park, and designed the landscaping and new construction herself. The association's cloistered grounds boast flower beds, shade trees, and picnic tables, not to mention a dance studio, an art gallery, telephones that actually work, an IBM personal computer, and a brightly decorated employees' cafe. Water being scarce in Managua—two days a week the supply is simply shut off—her garden of culture offers the strange but satisfying spectacle of sprinklers sprinkling with abandon.

On a typical morning, the massive gates of the presidential enclave swing majestically wide (or, rather, soldiers push them open) to make way for Rosario's chauffeured Datsun Laurel. She arrives at her headquarters seconds later, the commute between home and office being about two blocks.

" jHola!" she calls out as she flies past her secretary and several waiting companeros—her hair still wet, her arms busy with diplomatic cables and wellstuffed folders, which she drops on a conference table on the way to her inner office. "Mireya!" she shouts a moment later, and the svelte secretary, who has been typing Rosario's letter to Peter, Paul and Mary, fairly leaps up with her steno pad to take Rosario's dictation. "Dona Celinda!" Rosario beckons a bit later, and a stout, motherly woman rushes in with a stack of requisitions. Rosario signs each with a stately "R.''

The Cultural Workers Association boasts a staff of forty and a dues-paying membership approaching seven hundred. Painters, sculptors, poets, dancers, actors, musicians, even circus performers belong. For those who join, the association provides access to such scarce commodities as paint and canvas; musical instruments; ballet shoes; places to rehearse, perform, publish, and exhibit; all-expenses-paid trips to friendly countries; and a host of other privileges. For those who don't... well.. ."I don't know of any,'' Rosario says. "I don't know any dancers who don't. I don't know of any musicians. I don't know of any writers except two—do you?"

She means Pablo Antonio Cuadra and Mario Cajina Vega of La Prensa, the government-censored newspaper of the opposition. Ironically, Rosario herself worked for more than a decade at La Prensa, as personal secretary to Pedro Joaquin Chamorro, the anti-Somoza editor whose assassination in 1978 galvanized the forces that finally toppled the dictator.

Today Chamorro is a hero of the revolution, accorded the same honor as Ho Chi Minh: a major Managua thoroughfare bears his name. His newspaper, however, has become a counterrevolutionary villain, its reporters subject to harassment and occasional imprisonment. Rosario is remembered at the beleaguered daily as an uncommonly bright and ambitious young woman, with a penchant—according to the newspaper's current president, Violeta Chamorro, Pedro Joaquin's widow—for nervously biting her nails.

Using such pseudonyms as "Carolina," "Gabriela," and Berenice Valdemar," Rosario harbored revolutionaries in her house, smuggled weapons in her car, and went to jail.

"I wish I could tell you more," says Dona Violeta, "but I'm afraid it's just too dangerous."

Rosario joined the Sandinista underground in 1969, while working at La Prensa. She harbored companeros in her house, smuggled weapons in her car, and, like thousands of others, went to jail, spending twelve days in 1975 in a National Guard barracks with a pillowcase over her head. The previous year she had founded Gradas (Steps), a group of painters, musicians, and poets who engaged in revolutionary street theater on the steps of Managua's churches.

"This is the revolution that we made —the artists as well," Rosario says today. "It's not like another society, where you would find politicians on one side and artists on the other. ' '

Nicaraguan exile Xavier Arguello, onetime secretary-general of the Ministry of Culture, paints a less harmonious portrait. He recalls a meeting of the Writers' Union in 1982, called by Rosario to award the prestigious Order of Ruben Dario, named for the revered national laureate. When someone proposed La Prensa's Cuadra, one of the country's most distinguished poets, Rosario protested, "But he's not with the revolution." That settled, it was also agreed that nobody should write for La Prensa s literary supplement, and that anyone who did so would be banned from the Sandinista-sanctioned journals.

Arguello says Rosario's star zoomed ever higher as Daniel Ortega became first among equals in the Sandinista directorate and later, in 1984, president of the republic. By 1982, she was powerful enough to virtually exclude her rival, minister of culture and worldfamous poet Ernesto Cardenal, from preparations for the Ruben Dario celebration, a two-week fiesta that attracted artists and intellectuals from all over the globe.

At a reception during the fete, Arguello heard the minister complain bitterly, "That bitch! She's worse than Dinorah" (referring to Somoza's mistress). Cardenal—in his cups—went on in this fashion, to everyone's alarm, until the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko cut him off to plead: "Relax, Cardenal! Calm yourself."

These days, the Ministry of Culture, housed on Somoza's erstwhile estate, is, in Arguello's words, "a large, empty box." His appraisal is not contradicted by its quiet corridors, vacant desks, and one lone secretary, who informs a visitor that most of the ministry's staff has gone north to harvest coffee.

Rosario's headquarters, by contrast, are buzzing with her minions as she meets with the cultural attache to Sweden (subject: Rosario's impending visit), the Writers' Union (subject: a future meeting), and the subeditors of Ventana (subject: a personality clash arising from an ideological dispute). At a lunch for all her union officials, she sends them scurrying around the cafe, redeploying chairs and tables when the original arrangement does not suit her.

''We don't want to repeat the old folklore," she admonishes yet another gathering—this one of dancers. ''The people are tired of seeing the same thing. They need to see the fruits of the revolution. Let's have imagination, fantasy, and creativity. We want to recreate folklore."

Back in her office, a choreographer lauds Rosario's festive ensemble of cotton print dress, coral necklace, and myriad multicolored rings that cover her fingers. ''jPrecioso/" he exclaims. "/Elegante!" she replies, eyeing his Italianate weekend bag. "Ciao!" they say on parting.

Mireya brings coffee. The air conditioner chugs away. Hard at the task of remaking her country's culture, Rosario dons a pair of nondescript glasses to edit a Ventana article about ''The New World Information Order" and ''information imperialism" among the Western media. ''Too dense," she says, and sends it back for revision.

Against the tropical languor of Nicaragua's mushrooming state bureaucracy, she's all speed, efficiency, and almost frantic productivity. Above the table, the picture of competent authority. Below, her knees oscillate like hummingbirds' wings.

'I feel that all lives are lives of destiny. You never know what's going to happen to you, although you should know. I always have these premonitions when something wrong is going to happen. I can hardly ever bear going to a funeral. I'm so scared about the dead coming back and telling me things."

Zoilamerica Murillo, Rosario's late mother, was a niece of General Augusto Cesar Sandino, the sainted spirit of the revolution, who was executed half a century ago on orders of the first Anastasio Somoza. She was a practicing spiritualist who often attempted to contact the martyred general via seances, and other, less exalted spirits through the occasional Ouija session.

Rosario insists that her mother predicted her own death in October 1973, telling her after a tarot reading to prepare to lose someone close. Zoilamerica died a week later in a car accident, crushed between two softdrink trucks on the road to the Pacific Ocean. Only ten months before, Rosario's third child had been killed in the earthquake.

"I remember when I had to go to the morgue to get my mother. They opened the drawer and said, 'Is this your mother?' I was twenty-one. I was devastated. But, you know, with me, I'm very nervous and I get easily scared, but when it comes to facing big things like that, I seem to calm down."

Continued on page 98

Continued from page 64

Thus whenever she boards the national airline, Aeronica, she clutches a piece of crystal—a gift from Greta Schneider, the ''very spiritual" ex-wife of film producer Bert. ''It's a natural crystal," Rosario says. ''She's developing a perfume, you see, and she's going to have it sold in crystals."

As for the Republic of Nicaragua, it is redolent of portents, revelations, omens, ghosts—all suffused in a mist of atomized confusion. Rosario's father, Teodulo, has not really severed relations, it turns out. Indeed, she says he occasionally comes to dinner, "happy to eat what there is to eat, and drink what there is to drink, and then he says he's had a wonderful time and he leaves."

"But we know," Rosario adds, "that sometimes at parties he says things like 'Well, I hope the contras come soon, so that I can get my land back.' But then, on the other hand, he goes to my aunts' house and says, 'Oh, my God, I'm so worried about my daughter. What will happen if the contras get in? Where will she have to go?' So it's contradictory."

No more contradictory than Rosario herself—the dreamy poetess who oversees her fiefdom with an unyielding eye; the egalitarian revolutionary who revels in Ralph Lauren; the First Lady of a modest little country thrust by circumstance onto the proscenium of global conflict.

Arturo Cruz Jr., no friend of the Sandinistas, sees in Rosario a future Imelda Marcos, a comparison that at first blush strains the imagination. "But do you think that Imelda, twenty years ago, was as bad as Imelda today?" Cruz demands. "Of course not. She merely followed the logic of power, the natural logic of human passion. O.K., so Rosario won't have three thousand pairs of shoes—maybe it will only be a hundred."

At a Catholic church in Managua one evening, Rosario attends a special service for her daughter Zoilamerica. The tall, soft-spoken girl in camouflage fatigues has just returned safely from two months on a coffee-picking brigade near the Honduran border, a zone of frequent contra attacks. They slip into the pew in front of Lidia Ortega, the president's tiny, white-haired mother.

Rosario crosses herself, takes Communion, prays, sings the songs. In the middle of "Yo Soy Pecador" ("I Am a Sinner"), a favorite of her mother's, she hugs her daughter fiercely and breaks down, her singing voice suddenly hoarse with weeping. Tears smudge her mascara. Her dark eyes glisten. She emerges smiling and refreshed—ready to re-enter the revolution.

"If you believe that God is love," she says, "and that true love can achieve anything; when you believe that God is within yourself, because you are created in the image of God—so that means you are also God—then you can act with sureness and certainty, because all things are possible."

There is strange bliss in her voice.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now