Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

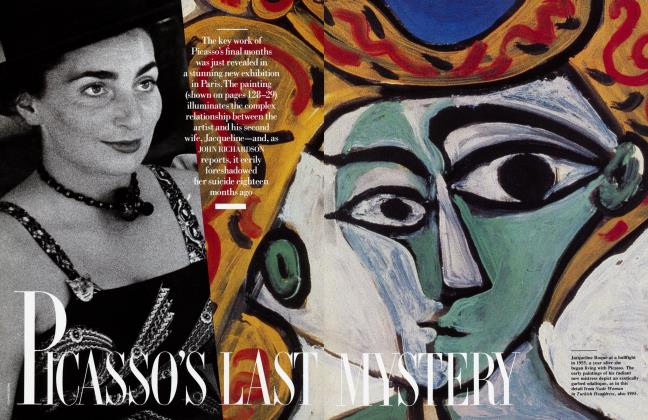

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFrom his fancy-dress days at Cambridge, through the Vogue years and his affair with Garbo, the flamboyant photographer-painter-designer-diarist recorded the passing parade. JOHN RICHARDSON reappraises

August 1986 John RichardsonFrom his fancy-dress days at Cambridge, through the Vogue years and his affair with Garbo, the flamboyant photographer-painter-designer-diarist recorded the passing parade. JOHN RICHARDSON reappraises

August 1986 John RichardsonCecil Beaton's memorial service at Saint Thomas Church on Fifth Avenue was impeccably staged— there were trumpets and Palestrina and an Irene Worth valediction—but it did not play to a very full house, We ushers hung about inside the door waiting for hordes of elegant mourners. In vain. No stars of stage or screen or disc materialized; nor (except for loyal Leo Lerman) did any representatives of the magazines or managements or film studios on which Beaton had shed such luster. Likewise, precious few of the gens chic whom he had drawn and photographed, flattered and diverted for fifty years or more made an appearance. I counted thirty-seven people in the church. And then, just as the organist broke into César Franck, a stretch limo drew up. Out stepped two dramatic-looking women—one quite tall, one quite short—each swathed in black, each leaning on the arm of an attendant: Anita Loos and Louise Nevelson. Two more striking mourners could not have been found; if only there had been a large marble urn against which to drape them. Cecil, who set such store by his image, would have been pleased. However, the far-from-full church did not strike me as auguring well for posterity.

How wrong I was! Someone had simply forgotten to mail the invitations to the memorial service. And far from fizzling out, Cecil's star has been very much in the ascendant these last six years. Too often dismissed in his lifetime as a frivolous pasticheur of the frivolous Baron de Meyer, Cecil has emerged as a natural photographer of great originality and sensibility whose influence crops up again and again in the work of eminent contemporaries. Successive auction sales of his stash of photographs and scrapbooks and drawings have done much to propagate his fame. And now we have a full-scale life, Cecil Beaton: A Biography, by Hugo Vickers (Little, Brown). Alas, Mr. Vickers has been so faithful to Beaton's diaries (145 volumes written over more than fifty years) that he diminishes his protagonist. For although an excellent case can be made for this sacred monster, Vickers does not begin to make it. Fortunately, another publication, Beaton in Vogue, by Josephine Ross (Clarkson N. Potter), to be published next month, captures the strengths and limitations of Cecil's ephemeral spirit. But no book, not even memory, can do justice to the snap, crackle, and hiss of Beaton's queer, dandyish wit: wit which at its best rivaled the firework brilliance of Jean Cocteau, and which harks back to the paradoxes of Wilde and the tradition of high-camp malice whose tone is first heard in Restoration comedy.

Besides wit, illusionism played a major role in Cecil's makeup, also improvisation. At a time when more serious practitioners of the arts were intent on making nothing out of something, Cecil was obsessed with making something out of nothing. Witness those early photographs in which he adapts the props and cliches of the old-time portraitist—the velvet drapes, the aspidistra on a plinth, the not-to-be-sat-upon chair—to his own evocative purposes. The "Picturesque" tradition at its last gasp. Cecil's sylvan settings in the dix-huitième manner were conjured out of silver mackintosh, bits of tinsel, and Michaelmas daisies dangling from the ends of billiard cues. As for those bun-faced girls of good family posing romantically in the foreground, it is hard to believe that they are the very same hung-over Bright Young Things whom Evelyn Waugh was simultaneously portraying in Decline and Fall and Vile Bodies.

And how deftly Cecil applied similar illusionistic methods to himself. The arbiter elegantiae of later years was entirely self-invented. In his early days he was a pretty but petulant youth who, when not fooling around with a camera, worked as a stringer for a gossip columnist, the Waugh-like Mrs. Whish. Anything was preferable to the family timber business, which was run by Cecil's dreadful North London daddy, "an annoying old fool and rather a common fool at that," according to his son. Mummie was not much better—genteel and too concerned with upward mobility— until Cecil did her over from toque to shoe buckles.

Cambridge had brought Cecil out of the closet with a vengeance. In his pastel accessories, heavy makeup, and lacquered fingernails (one of them an inch and a half long), he was the parody of William Plomer's "rose-red sissy half as old as time": forever swishing around in picture hats, trying to lure inebriated undergraduates into bed, but only if their blood was blue enough. "I'm the Gladys Cooper [Lily Elsie, Lillie Langtry, Gaby Deslys] of my time," he would boast in his weary, nasal drawl—like nylon ripping.

It did not take a social climber as dedicated as Cecil long to realize that the drag had to go. And so back to the closet it went—not to re-emerge (e.g., his brilliant self-portrait as Lady Mendl) until he felt more comfortable about his sexual orientation. But the self-contempt and sexual conflicts that Cecil himself diagnosed so accurately proved in the long run to be a plus rather than a minus. ("I have always hated fairies collectively," he told the designer Charlie James. "They frighten and nauseate me and I see so vividly myself shadowed in so many of them.") His fears fueled the rocket of ambition that propelled him into social and professional orbit, although there was the occasional setback. During Lord Herbert's coming-of-age party at Wilton—the family's great seventeenth-century house—the twenty-three-year-old Cecil was pounced upon by three drunken "hearties" and thrown, white tie and all, into the river that ran through the park. Cecil returned dripping to the ball, vowing that he would get even with them. Get even he did. By dint of sheer hard work and self-made charm he soon had the brighter members of the aristocracy, not to speak of cafe society on both sides of the Atlantic, eating out of his hand, vying not just for his services but for his company. Similar conflicts involving social and sexual shortcomings helped to propel another gifted North London boy: Evelyn Waugh. How he and Cecil loathed each other!

His wit rivaled the firework brilliance of Jean Cocteau.

Beaton's biographer claims that "Cecil will surely be remembered for his work on My Fair Lady more than for anything else." This, to my mind, does him an injustice. By virtue of their ephemeral nature, even the best theatrical costumes—for example, the ones by Cecil's master, Christian Bérard—are no passport to immortality. And by comparison with Bérard, Cecil's work for My Fair Lady is meretricious kitsch. No, Beaton is historically important because he was an eye-opening recorder of the passing show, a witness to his time. Like Horace Walpole two hundred years earlier, and Andy Warhol today, Cecil had a homosexual's flair for seizing on the Zeitgeist. Walpole, living as he did long before the invention of the camera, formed and recorded the taste of his day by means of constant correspondence. Warhol, living as he does in a technological age, has done much the same thing not just by painting portraits but by photographing virtually everybody he meets and often taping them, as well as keeping a diary. Beaton falls between these two extremes. True, his diaries and articles (less so his letters) are a bit flaccid—except when the gifted Waldemar Hansen has a hand in the writing—and not nearly as effervescent as his conversation. But all in all they provide a panoramic view of the social scene over the last fifty years or so, and of changing patterns in fashion and taste in every field from show biz to gardening. Through the gossamer there are also tantalizing glimpses of the foothills and occasionally the summit of Parnassus. And then what an extraordinary pantheon of people Cecil evokes in profiles as sharply focused as his photos—people as disparate as Mae West and Lucian Freud, Truman Capote and Kenneth Clark, Queen Mary and Picasso. By contrast, Cecil's drawings are mostly too facile or trivial to be of interest, except for his caricatures (little known because so libelous), which are masterpieces in the no-holds-barred tradition of Gillray. The ones of Vita Sackville-West and Anne, Countess of Rosse—who is the sister and mother of Cecil's two principal rivals, Oliver Messel and Lord Snowdon—are of a fiendishness that is beyond praise.

However, his photographs are Beaton's main claim to fame. It is easy to dismiss them (as Hilton Kramer did in the New York Times) as superficial, uncritical, shamelessly flattering, and technically faulty. But doesn't this amateurishness—which Cecil, as an English gentleman, felt obliged to cultivate—enhance the appeal of the early work? Cecil's mercurial view of the world—whether of pre-war country life as one long charade with half the guests in fancy dress, or of North African battlefields littered with burned-out tanks like Gonzalez sculptures—depended on minimal technical resources and maximum improvisation ("Would you stand in front of the fire to prevent those lurid Götterdämmerung reflections, and aim that hideous lamp at Caroline's pearls"—that kind of thing). His hit-or-miss approach stood him in good stead because it meant that he and not the camera had the upper hand, and that—so long as he was working in black and white rather than color (which he usually botched)—he could snap away with the speed of a machine gun regardless of all but the most elementary technicalities.

If that empty phrase "I am a camera" applies to anybody, it applies to Cecil and his snapshot reaction to life. But how outraged this touchiest of men would be to find himself identified with the aspect of his work which he regarded as déclassé. For his dream was to be God's gift to the theater. And not just as a set designer either, but above all as a playwright—a role for which his one major attempt (an inept and insipid play called The Gainsborough Girls, which he wrote and rewrote for over twenty years) proved that he had not the slightest aptitude. As Kenneth Tynan wrote, The Gainsborough Girls revealed that Cecil had "a simple and sentimental heart. . . .It was as if an avocado pear had been squeezed and discharged syrup."

Although he first made a reputation in London with photographs and drawings of the beau monde, which, as we can now see, are some of the most evocative images of the period, Cecil did not achieve real fame and fortune until he came to America in 1928 for the first of many visits, and ended up under contract to Conde Nast. For the next nine years Cecil did brilliantly— covering fashion, personalities, travel— for American Vogue. A pretty house in Wiltshire continued to be Cecil's base, but New York was his oyster, until in January 1938 he brought disaster on himself with an act of the utmost folly and nastiness. In a composite drawing—cocktail glasses, show girls, jazz bands, swizzle sticks, etc.—done to illustrate Frank Crowninshield's Vogue column on New York society, Cecil made a number of anti-Semitic observations in trompe l'oeil newspaper type so small that the naked eye could not decipher them. Alerted, probably by an art editor who loathed Cecil, Walter Winched challenged his readers to take a magnifying glass and read such sneers as "Mr R. Andrew's Ball at the El Morocco brought out all the damn kikes in town." Overnight Cecil became anathema, not least to Condé Nast, who insisted on his resignation. Everyone involved, especially the targets of Cecil's malice, behaved with exemplary restraint. Only the perpetrator gave way to shrill pique. ''I'm damn glad I did it," Cecil snapped at his friend David Herbert when he was safely back in England.

New York did not forget. Even when he returned to America in 1946, toughened and at the same time tenderized by the war, Cecil was mortified to find that his gaffe was still remembered. Jose Ferrer refused to allow him to do the sets for a production of Cyrano de Bergerac, because of his reputation for Fascism. And Vogue was at first reluctant to take him back to its bosom. However, the fact that Greta Garbo took Cecil to her bosom, such as it was, mitigated his despair.

Cecil's romance with Garbo was not a concept that his friends found easy to accept, let alone take seriously. At first he was tediously furtive, later embarrassingly m'as-tu-vu about it. And try as he does, Cecil's biographer never really succeeds in making this episode plausible. The trouble is that he overlooks the significance of certain facts which scream to be correlated. If this seemingly ill-suited couple were much better-matched than people realized, it was because they were both a bit androgynous. While Cecil saw himself as Gladys Cooper, Lily Elsie, et al., Garbo seems to have entertained occasional doubts about her gender. When they first met, in 1932, Garbo (who had evidently never been to Greece) told Cecil, ''You are like a Grecian boy. If I were a young boy I would do such things to you. . . " Twenty-four years later, when their affair had been running its zigzag course for a decade or so, Garbo said to Cecil, ''I do love you and I think you're a flop. You should have taken me by the scruff of the neck and made an honest boy of me."

Time and again Cecil plays up to Garbo's masculinity, for instance when he begins his touchingly stilted love letters ''Dear Sir or Madam" or ''Comrade" or "Please, my dear young man, do scratch a few lines to your ardent suitor." Endings are no less telltale: "I remain, dear Sir, your dutiful, humble admirer Beaton." In the long run Cecil's maidenly sensibility was no match for Garbo's piratical ego. After repeatedly leading him on and reducing him to a very lovesick "sir or madam," Garbo moved to other pastures. Meanwhile, egged on by Diana Cooper, Cecil embarked on an abortive flirtation with a charming English girl, sixteen years younger than himself, but this came to nothing. In the end (1963) he took up with someone far more suitable: a young art historian—Scandinavian like Garbo—whom he met in a San Francisco leather bar. They lived together for one of the happiest years of Cecil's life, but the boy eventually got homesick and returned to San Francisco. When he left, "it broke [Cecil's] heart," said Truman Capote.

Friendship with artists such as Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Patrick Procktor, and David Hockney gave Cecil the mistaken idea that he too could achieve fame as a modem painter. In 1966 he showed a large group of big, splashy portraits (the subjects were an odd assortment, among them Queen Victoria, Picasso, and Alec Guinness) at London's Lefevre Gallery. The critics gave Beaton the artist the same short shrift they gave Beaton the playwright. Keith Roberts (in the scholarly Burlington Magazine) hit the nail on the head: "There is embedded in [Beaton's] talent a vein of cork, which impels him irresistibly towards the surface of things, no matter how hard he strives to go deeper." Nor did Cecil's attempt to project a swinging new image sartorially—very flared suits of brightly colored stuff worn with sombreros—provoke much more than laughter, and a wickedly apt nickname from Cyril Connolly: "Rip-Van-With-It."

And then once again Cecil made a public fool of himself. Most of his adult life he had kept a diary, selections from which would from time to time be published. As a rule he was careful to pick entries which were more informative about friends or enemies than himself. Not so the sections (subsequently published as The Restless Years) which chronicled his affair with Garbo in a gush of self-serving, self-pitying schmaltz. When McCall's published extracts in November 1971, followed by Newsweek and later the British press, friends were appalled. So, it seems, was Cecil. Why had he come out with this maudlin document? One of Garbo's closest friends accused Cecil to his face of having done it for money, but the truth is Cecil did it out of vanity allied to notoriety—a passion for being the center of attention at any cost. "All the nicest things about [Garbo] are lost in a haze of her selfishness, ruthlessness and incapability to love," he confided to his diary in justification of his conduct. "Let her stew in her own loneliness."

The fact that Cecil was knighted in 1972, at the height of the Garbo uproar, did a lot to palliate his own and other people's feelings, but the damage to his psyche had gone deep. And the severe stroke that Cecil (aged seventy) suffered in 1974—it left the right side of his body permanently paralyzed and affected his memory, particularly for names —was almost certainly a consequence of it. As a critical colleague pointed out, there was a terrible irony in the way the illness struck at two of Cecil's principal faults: his vanity and tendency to namedrop. At first he couldn't write or draw or use a camera. "If I had a gun, I'd shoot him," said his greatest friend, Diana Cooper. Fortunately she didn't, for thanks to his iron will and courage, Cecil was back at work within a year, using his left hand instead of his right. In my opinion the left-handed drawings are an improvement on the right-handed ones; their pertinacity and clumsiness are infinitely preferable to the glibness of earlier work. Cecil's photography, however, suffered more; he had lost that easy, confident, gestural—one might almost say conversational—way of using a camera that had been peculiarly his.

An American friend, Sam Green, who was often in attendance, testifies that Cecil continued to be as alert and amusing a companion as ever. It was Sam who attempted to effect a reconciliation between Garbo and Cecil after the bad blood caused by his breach of confidence. Thanks to Sam's efforts, Garbo overcame her resentment sufficiently to pay her former lover a visit in the country. It was decent of her to go, less decent to get her revenge. At first she put on a marvelous performance, chatting away, even sitting on Cecil's knee. And then, as he hobbled painfully into luncheon, she said to the secretary, "I couldn't have married him, could I? Him being like this!" At the end of the visit, Cecil made as if to embrace Garbo. "Greta, the love of my life," Sam Green heard him say. But Garbo shuddered and shook him off and went over to sign the visitors' book with her full name—something she didn't ordinarily do. Garbo never saw Cecil again.

And then in 1977 Sam arranged for Cecil to pay one last visit to New York. We all had lunch at Quo Vadis. Despite paralysis, Cecil was as funny and bitchy as ever. His inability to remember names, while remembering almost everything else, gave the conversation crossword-puzzle overtones. Little by little one learned how to interpret his mnemonics: "hotel named after her family" meant Mrs. Astor; "daughter has a very important job," the Queen Mother; and so forth. When lunch was over, I helped maneuver Cecil into his car. It was quite a task. The paralyzed right leg was recalcitrant—"just as unmanageable as a debutante's train," said Cecil in that all-too-imitable drawl. "Kick it! Like me, it doesn't feel a thing." And with a defiant toss of his sombrero, the old trouper drove off— where else but to Vogue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now