Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE NOISE BOYS

Mixed Media

Two new collections of old rock criticism are music to deafened ears

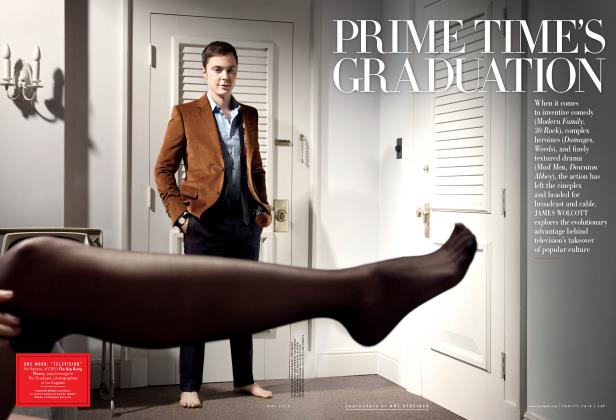

JAMES WOLCOTT

Three decades after Elvis Presley anointed Eros with hair oil, rock criticism has grown rather grim and jowly. While rock music has replenished its roster with glossy new faces to reflect light on the old (best example: Whitney Houston paying homage to Aretha Franklin in her "How Will I Know" video), rock writing has had the same stoic slabs of cheese striking Rodin's The Thinker pose for lo, these many years. John Rockwell, Jon Pareles, Jay Cocks, Ben Fong-Torres, Stephen Holden, Robert Palmer, Robert Hilbum, Robert Christgau, Dave Marsh—these are just a few of the living statues capable of tearing open record cartons with their bare hands. When some of these older scribes raise a hurrah for the Replacements or the Beastie Boys, it's because such slobbo rowdies take them back to what they wish were their own glory days of spewed beer and fondled titty, to the days when they were the boys of noise, piling up review copy at Cheetah, Creem, Rolling Stone. And what of the women? Female rock critics are a vanishing few. Ellen Willis, the former rock correspondent for The New Yorker and once considered the Rosa Luxemburg of riffs and body politics, has opted out of the current tumult to become a bobby-soxer for the peace-love music of the sixties. With the noise boys locked in a huddle, rock criticism has become a mode of discourse as coded and insular as semiotics, a mantra for the elect—a catechism for those who write by rote. Wasn't always so.

In the heyday of rock writing, critics didn't dispense eyedropper opinions; words were poured like paint upon a pinwheel, for a psychedelic swirl. A rock mag named Crawdaddy! used to peer at rock albums as if through a stained-glass window, seeking celestial design and acid-trip revelation. Doubtless this resulted in impressionistic spill and overkill, every crack in Janis Joplin's voice traced to a dry riverbed in Texas, every guitar lick from Jefferson Airplane a brushstroke twig on the tree of life, but there was a heady kick to language and analysis gone happily amok. It was similar to the show of colors that the New Journalism briefly unfurled.

As if to kick-start rock criticism's sluggish system, yet another practitioner, Greil Marcus—the author of Mystery Train and currently a glowing tapeworm in the dank bowels of postmodernism for Artforum—has consulted the archives and dusted off a pair of rock writers renowned for their raucous disdain of tact, decorum, and tidy expression. Earlier this year Marcus supplied the intro to a reissue of Richard Meltzer's The Aesthetics of Rock (Da Capo), seeking to cast upon the book the aura of a status object. First published in 1970, "7%e Aesthetics of Rock does not read like an artifact of some vanished time, but like an oddly energized version of real cool academic discourse. ... It will soon be, in certain circles, the coolest book to be seen carrying." Marcus has also introduced and edited a major chunk of collected rockcrit by the late Lester Bangs punkily titled Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, which Knopf made available for cool display last month. Of the two, Bangs is the prize exhibit. Full of bullinsky as Bangs could be (and he was the first to admit it), his was a unique, unsilenceable voice.

It's a voice that manages to bulldoze its way even through Marcus's editorial misjudgments. Putting together this anthology was clearly a labor of love for Marcus, who was Bangs's friend and colleague, but he sets up a lot of clutter that the reader needs to discard to get to the real buzz. In The Book of Rock Lists, the citation for Lester Bangs under the heading "The 10 Best Rock Critics" reads in part: "Most influential critic, best stylist, renegade taste that frequently doubles back on itself"—which seems fair enough. Marcus goes further. "Perhaps what this book demands from a reader is a willingness to accept that the best writer in America could write almost nothing but record reviews." Such hyperbole is a hindrance to appreciating Bangs, who was not America's greatest writer (dream on) but a novalike talent who exploded the recordreview personality-piece formats of hack rock journalism. And when Marcus confides, "As a writer who has often fantasized his own death, I imagine that all writers fantasize their own deaths," the logic is dubious, the disclosure presumptuous. If Marcus wants to get personally weird, let him do it in the pages of Artforum, where no one cares. Lester Bangs hardly fantasized the death he received, as Marcus himself admits. (An addictive personality who wrote reams on speed and swigged Romilar at parties, Bangs expired quietly in his sleep in 1982 at the age of thirty-three from complications involving influenza and an intake of Darvon. His overdose was a tragic fluke, coming at a point in his life when he had fallen in love and kissed off his Charles Bukowski barfly flexes of brain waste. Death snuck up on him like a thief.)

One could also quibble with Marcus's selections. He omits Bangs's scathing put-down of Bob Dylan's ode to the gangster Joey Gallo, in which Bangs contrasted Dylan's lyrics with Gallo's actual deeds to demonstrate how dumb and falsifying Dylan's mythmaking was. Instead, Marcus clots the text with hollow chest thumps from Bangs's unpublished, unfinished novel and a book proposal that reads like a loose transistor from Norman Mailer's Why Are We in Vietnam? It's Lester Bangs the bebop artist of scat-man prose that Greil Marcus wishes to preserve, but a lot of Lester's solos went nowhere fast for lack of subject. When he had a subject worth his powerhouse wit, however, he could muster a flurry of notes to gale force.

What special gust did Lester Bangs bring to the party that's been missing from rock criticism since? For one thing, an impudent humor. The impudence carries over to Bangs's attitude toward rock stars, most of whom he considered to be sequined carcasses spouting cosmic inanities. The major tiff in Psychotic Reactions is the feud Bangs carried on with Lou Reed in the pages of Creem (where Bangs was editor and star writer), which reads like Fred Allen and Jack Benny exchanging insults on Dexedrine. Lou Reed, the naked skull that skulked, and Lester Bangs, the conscience that laughed, were a perfect comic match. Not even the Freudian section heading, "Slaying the Father" (groan), can take away from the fun. Warming up, Bangs calls Lou Reed a liar and a lummox and a Judas to his own cause. "Lou Reed is the guy that gave dignity and poetry and rock 'n' roll to smack, speed, homosexuality, sadomasochism, murder, misogyny, stumblebum passivity, and suicide, and then proceeded to belie all his achievements and return to the mire by turning the whole thing into a monumental bad joke." Yet it is a howling wind that whistles through Lou Reed's bones. "Lou Reed is my own hero principally because he stands for all the most fucked up things that I could ever possibly conceive of. Which probably only shows the limits of my imagination." When Reed released Metal Machine Music, a tworecord sonic migraine that appeared on the scene like the black slab from 2001, an opaque herald awaiting an inscription, Bangs entered the outer limits of his imagination. In a state of rapt Nirvana, he burst forth with thousands of words on Lou Reed's buzz-saw baby, including a list of reasons Metal Machine Music was the greatest album ever made. "If you ever thought feedback was the best thing that ever happened to the guitar, well, Lou just got rid of the guitars." Lester was fond of feedback. Like the legendary producer Phil Spector, he erected in his mind immense walls of sound. Raw spires of dissonance above a dense fortress. It was Lester Bangs, after all, who popularized the phrase "heavy metal."

Indeed, the most apt epitaph for Lester Bangs and his brand of mondo-bondage manic-depressive criticism comes in the book from the guitarist Bob Quine (he played with Richard Hell's band), who says to Lester, "I've figured you out. Every month you go out and deliberately dig up the most godawful wretched worthless unlistenable offensive irritating unnerving moronic piece of horrible racket noise you can possibly find, then sit down and write this review in which you explain to everybody else in the world why it's just wonderful and they should all run right out and buy it. Since you're a good writer, they're convinced by the review to do just that—till they get home and put the record on, which is when the pain sets in. They throw it under the sink or somewhere and swear it'll never happen again. By the next month they've forgotten.. .so the whole process is repeated again with some other even more obnoxious piece of hideous blare.... You know, I must say, I have to admit that's a noble thing to devote your entire life to."

Yet it would be a mistake to chalk up Bangs's brand of rockcrit excess as Dadaism with a dental drill. There's a humanism in Psychotic Reactions that reaches much deeper than mere politics. (Which is what most rock critics practice today: socialism with a stony face.) This fellow feeling animates the passages about touring with the Clash, the farewell to Elvis, the achingly vivid portrait of Iggy Pop, and the obit on the punk-rocker Peter Laughner, who shriveled in fast motion before Bangs's eyes and died of drugs. This one-on-one sympathy is what distinguishes Psychotic Reactions from The Aesthetics of Rock. Richard Meltzer's wired work habits had certain similarities to Bangs's: "I'd get up in the morning, smoke some dope, put on an LP, enter its, uh, universe, take profuse notes, play another album, jump from cut to cut, make the weirdest of plausible connections (no professors—wheeee!—to monitor the hidebound topicality of my thoughts anymore), more notes, more records, occasional meals and masturbation, more more, then hop in the car and drive to Boston for Jefferson Airplane—or Asbury Park for the Doors—and home to write it up on my sister's diet pills." (They never talk this way in The Paris Review.) And Meltzer's free-associative meltdown in the very grooves of the album he was listening to also recalls Bangs. "Like Lester Bangs," blurbs John Rockwell, "Richard Meltzer writes about rock with prose that aspires to the spirit of the music."

But where Bangs, all heart and bear hug, wrestled with rock in the palpable present (he always wanted to know, "What does this make me feel?"), Meltzer superimposes his blown mind on the music in order to conjure up fleeing phantoms from The History of Western Thought. "The Angels' 'My Boyfriend's Back' presents the entire panorama of the arrival of Orestes." "Moreover, 'Ain't That Just Like Me' by the Searchers can be examined for its affinities to Marcel Duchamp's sex machine metaphor." Greil Marcus isn't completely screwy when he claims that The Aesthetics of Rock approximates the spirit of academic discourse (deconstruction, semiotics): this book, so packed with allusions, thorny formulations, and oracular asides, is kinda Derrida. It's a thin-air book, a dizzy penthouse view of pop culture, a ghostly body just barely supporting a jack-o'-lantem head. Meltzer's province isn't rhythm or emotion but, as Marcus himself notes, words—verbal noise. Meltzer is brilliant in spades, but how far can you go? Language having a self-conscious nervous breakdown has been done to death in literary criticism, and it's hardly a more appealing spectacle when the subject is rock lyrics. Pedantry and put-on combined make for a project as dead-end as Flaubert's dictionary of cliches in Bouvard et Pecuchet. The mind is a terrible thing to fritter.

Which both Bangs and Meltzer in their different ways understood. Meltzer has pretty much given up writing about rock, and before his death Bangs was trying to phase himself into more personal graffiti. Both have left a large residue of influence on the outskirts of pop journalism. Hard-core fanzines devoted to punk and heavy metal owe their scrawling bravado to these two, and there is a cadre of writers at the Village Voice (RJ Smith, Chuck Eddy, Greg Tate) trying awfully hard to be the noise boys of the eighties. But, face it, the thrill is gone. (Perhaps for the musicians too—T-Bone Burnett recently lamented that "it's all become professional now. Rock 'n' roll is a museum.") Not only has rock writing become doctrinaire, reflecting the opinions and priorities of its commissars, but it's been superseded by music video. In 1987, one would deconstruct pop music not linguistically, a la The Aesthetics of Rock, but imagistically, via MTV. (And already we've had decodings of Madonna's lingerie and Dwight Yoakam's rodeo finery.) Rock videos don't allow the viewer and listener to free-associate; they supply the associations for you. The looming pictures of icecapped mists and dinosaur bogs that Led Zeppelin once conjured in the imagination are now plopped down in plain sight and photographed at Caligari-askev/ angles. Rock videos are a series of retinal quickies, too punchy to be subliminal, too scattered to have true impact. One thing about noise is that it has heft and duration. It's a beast that sits on your chest and stays awhile. It generates obsession rather than distraction. From this behemoth of feedback and squalling guitars Bangs and Meltzer at their best were able to tear off terrific hunks of bombast. There's noise aplenty in rock and rock criticism now, but it'.s an empty, joyless din. The heart has gone out of the holler.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now