Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

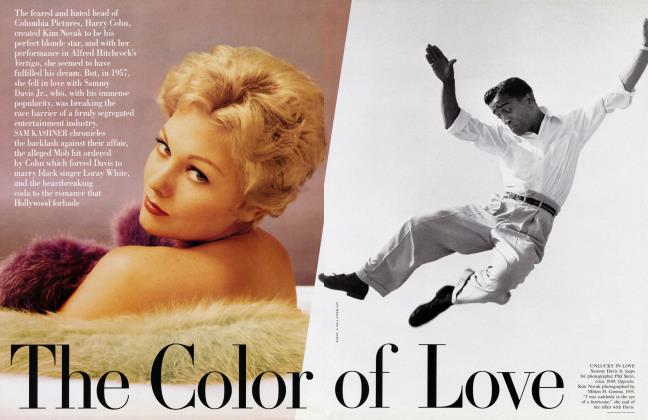

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowKANDY MAN

BRUCE HANDY

The original Batmobile, the Porsche in which James Dean died, Elvis Presley’s gold Cadillac, the cars in hundreds of TV shows and movies♪all were customized by George Barris, whose Kandy Kolored vision, described by Tom Wolfe, has changed the culture of cars

The Customizer

The garage at Barris Kustom Industries in North Hollywood looks like the garage at any other Valley body shop—which is probably to say it looks like the garage at any body shop in the country. There are oil stains on the cement floor and colorful girlie posters on the walls promoting not-so-colorful automotive products; outside, there is even a pit bull on a chain relieving itself in the shade between junked cars. What makes the garage at Barris Kustom worth visiting is that the Batmobile is parked there—by which I don’t mean the cartoonishly overdesigned Batmobile from the Tim Burton-Joel Schumacher movies that no one will remember in another 10 years but the real Batmobile, the bubble-domed one from the 1960s Batman television series, the one that, more than 30 years after its debut, retains the sleek muscle-car menace that transcended the show’s droll campiness. It’s not just nostalgia: there’s something still fresh about the Batmobile, just as there’s something still fresh about so many other mid-60s artifacts, from back before the decade got so self-serious—Richard Lester movies, Caesars Palace, “Satisfaction,” the young Julie Christie.

George Barris is showing me around. He is the man who styled the Batmobile and who owns Barris Kustom, the man who came up with that snazzy K-for-C swap somewhere back in the 40s, when he first set up shop; if you know what a chopped Chevy is, you already know who George Barris is—the King of the Kustomizers, as he styles it. I begin with the Batmobile because it is not only the car he is most famous for but also—life doesn’t always work out this wayone of his finest and most quintessential works. On this day, however, the Batmobile, recently back from a stint at a Barris exhibition at Universal Studios, is looking a little long in the tooth. The red-orange trim is faded, the interior slightly tatty, and someone has stuck big yellowing, Post-It-like stickers all over the vehicle’s exterior, pointing out the Batchutes, the oil squirter, the nail spreader, even the gas intake—I didn’t expect the Batmobile to vaguely resemble my refrigerator door. Still, just seeing the thing is a childhood dream come true. / am in the presence of the Batmobile. It is as real as my Honda Accord (not a childhood dream, by the way). Can we start it up, I ask, just to hear the engine kick over, to hear that atomic-turbine howl, that sonic baby-boomer madeleine? But no, Barris tells me, the Batmobile’s battery is disconnected. Oh well, no need to bother gradeg school friends I haven’t spoken to in years.

Barris is a small man with a certain physical grace that he has kept well past middle age (he has politely asked me not to reveal how far). Aside from his other accomplishments and titles he can fairly be named the Edith Head of cars: in one capacity or another, he has contributed to just about every movie and TV show with interesting cars you can think of and many more that nobody besides Quentin Tarantino remembers. Dozens of his films are represented by posters on his showroom walls, which besides serving as a de facto resume offer a history lesson in the use of the ellipsis in the marketing of several generations’ worth of teen-exploitation movies— from Hot Rod Gang (“Crazy Kids ... Living to a Wild Rock and Roll Beat!!”) to The Van (“Bobby Couldn’t Make It ... Til He Went Fun-Truckin’”). A more memorable list of his film and TV work would include Rebel Without a Cause, High School Confidential!, The Munsters (that series’ hot-rod hearse is parked in Barris's garage next to the Batmobile), The Beverly Hillbillies, My Mother the Car, The Love Bug, American Graffiti, both Cannonball Runs, The Dukes of Hazzard (the General Lee is out in the sun next to the red Torino with the thick white stripe from Starsky and Hutch and a Back to the Future DeLorean), Knight Rider, Blade Runner, Jurassic Park, The Flintstones. All told, Barris’s services have been used by hundreds of TV series and movies. He himself doesn’t even know how many, though he is a famously adept selfpromoter, which isn’t to say he comes off as one. “For a man that is a legend in his own time he is modest, easygoing and very enjoyable company.” That’s a line from an old Barris Kustom press release, which pretty much gets him right—including the fact of his having issued it.

Covering his showroom walls below the movie posters are frame-to-frame photos of Barris posing with at least a couple hundred show-business celebrities, from Alisters to B-listers to the merely good-looking, blow-dried, and forgotten. Celebrity commissions represent a significant portion of Barris’s oeuvre, and over the years he has turned out all manner of gold-plated Cadillacs and fur-lined Mustangs and Bentleys with psychedelic paint jobs for the likes of—pardon another list—Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Elvis Presley, Liberace, Sonny and Cher, Steve McQueen, Clint Eastwood, Bob Hope, Roy Orbison, John Derek, John Lennon, John Travolta ...

Every year, John Wayne had Barris raise the roof of a new station wagon to a more Duke-worthy level.

... John Wayne, who every year had Barris raise the roof of a new-model station wagon to a more Duke-worthy level.

... Adam West, who as Batman drove the Batmobile and as himself drove an Excalibur with a custom paint job that he remembers as “a little bit conservative” and Barris remembers as being emblazoned with Batman insignia and racing stripes. ... Barry Goldwater, who in 1955 had Barris fit a Jaguar XK 140 with airplanestyle gauges and controls. Now owned, Barris says, by some “East Coast doctor,” the car is out back in pit-bull land, awaiting restoration.

... Barry White, who had Barris finetune his all-white Rolls-Royce and all-white Lincoln Mark IV in 1974. “George,” he says today, “used to tighten me up and make me look real good in them cars.” Which is precisely the point. “These kind of guys have got everything in the world, but things like that really made them feel great.” Barris is telling a story about Sinatra and Martin, about the time he customized twin dual Ghias that they then gave to each other for Christmas, Frank getting a black one, Dean dark-green, each tied up with big red ribbons and snuck into the other guy’s garage. It turns out you can learn a lot about famous people, as you can about most people, from how they relate to their cars: “Frank”—Sinatra again—“was very safety-oriented. He wanted the car to be like his airplane. That means, if your master cylinder went out, you had a backup. If your fuel pump went out, you had a backup. Dean was the opposite. ‘Hey, whatever comes, goes, just make sure it runs, try and keep it polished.’ He was just an off-the-cuff guy. He was great.” And then there are the gear heads: Jay Leno, Tony Danza, James Garner, and the Smothers Brothers are all “very performance-oriented.” Zsa Zsa Gabor, I was surprised to learn, “was very car-oriented.” When Barris was working on her gold Rolls “she would come over in her coveralls and climb in the seat” and instruct workers as to precisely where she wanted her retractable wooden bar, with its sterling-silver wine goblets, and her goldplated makeup kit. (This was not the Rolls, by the way, in which she was pulled over by the Beverly Hills police officer whom she memorably slapped.)

The question of taste is a thorny one. “I never had a purple car in my life!” a horrified Miss Gabor exclaims when I ask about a paint job Barris remembered doing for her but that must have been for someone else. If he himself has ever had qualms about the things he has been asked to do to expensive cars, he doesn’t let on. “Kinky” is a favorite adjective, but he uses it in a purely descriptive rather than pejorative form. “Alice Cooper, he was a kinky guy,” he explains in the dry tone a dentist might use to describe a rotten molar—not pretty, perhaps, but nothing to ruffle a pro. His wife of 40 years, Shirley, is an attractive older woman who rides motorcycles, has her nails done in orange with blue and purple swirls, and exudes a palpable joie de vivre. She helps her husband out with fabrics and whatnot for Barris Kustom interiors, and she shares her husband’s equanimity. “In those days, I thought hot-pink patent leather was outlandish,” she says, recalling a mid60s upholstery job. “But that was Cher.” Cher, who gave her a go-go boot as a sample.

“What is the premise of the car?” George asks. “Is it something they’re going to use for a drive car? Or maybe it’s just something they always had the impression they wanted to have.” Like the orangeand-lime-green interior of Farrah Fawcett’s 1980 “Foxy Vette” or, for Liberace’s 1954 Eldorado, the sterling-silver grand-pianoshaped hood ornaments that opened up and played “I’ll Be Seeing You.” Barris tells what I take to be a not atypical story, about David Carradine: “He came in, proud of his BMW, and wanted me to take out the seats. ‘I want a Pakistan carpet,’ he says. ‘I’m going to sit on the carpet—put a backrest there for me.’

When Barris worked on her Rolls, Zsa Zsa Gabor “would come over in her coveralls and climb in the seat.”

“I said, ‘What color do you want to paint the car?’

“He said, ‘I’d kind of like the color like a peach.’ He had a brown bag with him. I said, ‘I’ll find some samples.’

He said, ‘This is what I want.’ I opened the bag and there was a peach.

“So I said, ‘You want it like that?’

“‘Yeah.’

“‘You want the fuzz and all?’

“‘I want fuzz and all.’

“So I put a certain flaky pearl in the paint there to give it that fuzz look.” And who’s to say what the rest of us might come up with had we the nerve and wherewithal? Isn’t self-expression part of the base romance of car ownership, even if that only means a vanity plate, an alumni sticker, or the pre-sets on your radio?

“I liked him,” Barris says. “That Carradine kid was all right.”

Darris Kustom Industries is just a fiveminute drive down Lankershim from Universal but seems to inhabit another world entirely. The showroom, with its beige brick and painted plywood exterior, dates from a period in the late 50s when commercial architects simply didn’t give a shit (there’s no better way to put it—even the 9 Os-era EZ Lube across the street can make a greater claim to style). Barris himself, though he must be worth millions in cars alone, dresses in giveaway T-shirts and sweats—he could be, I don’t know, the manager of a minimart. His secretary is a thin, handsome woman who looks as if she stepped out of a Walker Evans photo; his accountant could pass as a roadie for ZZ Top. Though movie stars help pay the bills, Barris Kustom resides in the “other” Southern California, the noncoastal Southern California, the Southern California settled by working-class immigrants and Okies and people whose children grew up to write those crank letters to the L.A. Times op-ed page. In short, it is the Southern California that reminds you the state is still part of the West, contiguous with Nevada and Arizona, not Oz or New York.

Barris himself grew up in Sacramento, raised by an aunt and uncle who ran a hotel and restaurant. He and his brother Sam, who was his partner through most of the 1950s, were pioneers in the strange new art of hacking apart and reconstituting cars— arguably they were even the first, at least in what a curator for L.A.’s Petersen Automotive Museum refers to as customizing’s “modern idiom.” Before the war, it had been a rich man’s indulgence. “George popularized it,” says the curator, Leslie Kendall. “He did radical things that appealed to the masses.” That included practices such as “chopping” (lowering a car’s roof), “channeling” (dropping the chassis), “frenching” (smoothing out the headlight contours), and otherwise stripping off all extraneous details—that would mean things like chrome trim and even door handles— for a zoomy, streamlined, ground-hugging look, the Nike Swoosh in steel and lacquer. Perhaps the most famous example of the classic Barris style is the chopped black Mercury James Dean drove in 1955’s Rebel Without a Cause—the one whose flashy airs prompted the movie’s teen hoodlums to puncture its tires. “It was,” George admits, “pretty hot-doggish for that period of time.”

He and Sam, their colleagues and rivals, shared not only an aesthetic but an attitude. In a time of increasing mass production, a time when TV dinners were a thrilling novelty, they refused to accept what Detroit wanted to give them. They were a greasestained little subculture striking one of the first postwar blows against conformity— Beatniks without the bad poetry. The Barrises’ movie work began when Hollywood noticed that kids had a lot of disposable income to blow on hot rods and custom coupes; studio executives figured they might spend some more of it if they saw the best cars on-screen.

Clark Gable and Lionel Hampton were the first celebrities to come nosing around, both seeking boss paint jobs and a bit of body work.

Barris met James Dean on the set of Rebel Without a Cause (besides supplying the chopped Merc, Barris also consulted on the famous “chicken run” scene). The actor and the customizer quickly became what he calls “car buddies,” hanging out in the shop, racing together.

“Most of the people that went out racing at that period of time didn’t like to race with Dean, because he was a daredevil. In the 50s you’d drive off the street with your Jaguar or your Porsche, race, and then drive home. Dean would go in there and hit a few hay bales. He went out to win. He didn’t go out to Sunday-drive.” Nicknamed Little Bastard by director George Stevens (according to Barris), Dean had Barris’s shop hand-letter it onto the back of a brand-new aluminum-skinned Porsche Spyder so that other racers would know whose dust they were eating.

In September 1955, Barris delivered the Spyder to Dean at a gas station on Ventura Boulevard in Sherman Oaks, where Dean lived, so he and a mechanic could drive it up north to Salinas for a race later that week. Though Barris insists that, off the track, Dean was “very safety-conscious,” he was doing around 85 when an engineering student in a Ford started to make a turn onto the highway in front of him. His famous last words (the mechanic survived to repeat them): “He’s gotta see us. He’s gotta stop.”

A year later Barris bought the wreck from Dean’s family and toured it around the country—for use in highway-patrol safety campaigns, he hastens to add. This sideline lasted until 1960, when the Spyder was somehow stolen in Florida, a theft not discovered until the car’s trailer turned up empty back at Barris’s in California; only the registration papers were left. The mangled Spyder has yet to be found, making it the Amelia Earhart of celebrity-death cars. An even bigger mystery is why someone would want to have James Dean’s death car without being able to brag about it openly to his or her friends; perhaps it was sold to a secretive billionaire wreck connoisseur. At any rate, Barris continues to get tips as to its whereabouts, and a few years ago, Jay J. Armes, the well-known detective with hooks for hands, tried to track it down as a favor. But still no luck. Barris re-created the Spyder for the little-seen 1997 film James Dean: Race with Destiny (Casper Van Dien played Dean). That Spyder now sits in the Barris Kustom showroom, next to the talking car from Knight Rider.

“Most people didn’t like to race with Dean, because he was a daredevil,” says Barris.

The other star Barris remembers most fondly is Elvis Presley, for whom he customized a number of cars, including, most famously, a 1960 Fleetwood Cadillac with gold-plated trim and hubcaps. The cabincruiser-style interior came complete with portholes (“Elvis liked the yacht feel”) as well as a gold-plated TV, a gold-plated record player, a gold-plated refreshment cabinet, and a gold-plated shoe buffer (impressive, though less golden than Zsa Zsa Gabor’s Rolls). Shirley Barris remembers another detail: “In Elvis’s car we had to have secret compartments. He would have protection ...” She hesitates. “I don’t know if I should tell you this. He would just have secret compartments for protection—and makeup compacts for ladies and anything people might need to primp themselves.” I assumed by “protection” Shirley meant condoms for the gallant singer. George told me later it was guns.

Perhaps the greatest service the Barrises ever did for Presley was boarding his future wife, Priscilla, then 16, at their home during her first visit to Hollywood, in 1962. “He was such a gentleman,” Barris says, “that he wouldn’t let her stay at his house,” which, after all, was full of “all these rock ’n’ rollers and stuff.” Priscilla’s visit with the Barrises was largely uneventful—“She was great,” George says—except for the time Elvis was critical of a new bouffant and made her weep. I mention to Shirley that Elvis must have placed unusual trust in the Barrises, given both his protectiveness of Priscilla and her status as jailbait. “We were sort of a square couple,” explains Shirley. “We were just a really married couple with kids. We weren’t into the drug scene, although we were with some of the biggest people in the industry—you can imagine what was going on with those stars. It was all over the houses and you could have whatever you wanted.” George claims he never so much as touched a beer, even in his drag-racing days.

By the early 60s, Barris was a successful, well-established businessman, even as his designs, reflecting the times, got stranger and more rococo (his brother Sam had left, returning north to Sacramento to be with his family). Then, as now, the profession’s real money was in licensing deals with toy and model manufacturers. Detroit, eager to tap into the booming youth market, sought him out as a consultant, as did corporations like Oscar Mayer, for whom he helped engineer and build the Wienermobile from someone else’s design (Barris himself designed a Wienermobile Sport Roadster that is still, alas, on the drawing board). By this time he was also manufacturing his own line of paints: the Kandy Kolors, originally a three-coat process that made your car look like a translucent, metal-flecked lollipop. The Kolors had wonderful, Pop-art names: Kandy Apple Red, Kandy Tangerine, Organic Blue, Pagan Gold.

He was thus quite well known, at least to readers of hot-rod magazines, when, in 1963, Tom Wolfe brought him to the attention of mainstream America—or at least Esquire readers—with one of the first important pieces of New Journalism, “There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy Kolored Tangerine-Flake Baby.” Here’s how Wolfe fashions Barris’s entrance: “He is a good example of a kid who grew up completely absorbed in this teen-age world of cars, who pursued the pure flame and its forms with such devotion that he emerged an artist. It was like Tiepolo emerging from the studios of Venice, where the rounded Grecian haunches of the murals on the Palladian domes hung in the atmosphere like clouds. Except that Barris emerged from the auto-body shops of Los Angeles.” A page later Wolfe is comparing Barris to Picasso, then Brancusi, then, a few more pages after that, Benvenuto Cellini. “You have to reach the conclusion,” he writes, “that these customized cars are art objects, at least if you use the standards applied in a civilized society.”

“I thought hot-pink patent leather was outlandish,” recalls Shirley Barris. “But that was Cher.”

To 90s ears, it may sound like overkill, but you have to remember that Wolfe was writing at a time when taking John Ford and Howard Hawks seriously was a novelty, let alone customizers, casino architects, or graffiti artists, and so Wolfe had to push his point. Barris is an extremely gifted craftsman with a seemingly innate, organic vision—which I guess sounds like an artist to me too. I suppose you could also make the case that in taking existing forms and reworking them to their own purposes he and his fellow customizers were among the first postmodernists, appropriationists long before anyone had heard of Michael Graves, Sherrie Levine, or Puff Daddy.

The celebrity jobs Barris does are mostly about decoration—hey-I’m-famous paint jobs and glammy, goony interiors. What he’s really about, what gets his juices flowing, is playing around with a car’s form. To hear him describe it, it’s almost a reflexive impulse—just the way his mind and eye work, something he’s always done (one of his early memories is of customizing his first bicycle with streamers and a flashlight). The day I visit his shop he is driving a Cherokee, a comparatively smallish sport-utility vehicle that he had fixed up for himself and painted a rich, luminous, liquid-buttery sort of gold, “pearl gold,” his signature color. “I couldn’t stand driving a stock car”—for a customizer that would be a source of great shame, like a samurai’s losing face—“so I slotted the taillights so that they got a more modern look, molded the spare tire right into the trunk for a continental look.” He also pulled out the front end a bit to give it the snouty appearance he seems to favor in design after design.

But the Cherokee work was seemingly a series of little deals, a nothing job. “How many guys would take a Ferrari and slice it down the middle?” he asks, referring to another of his drive cars (he says he has 10 to 15, depending on his mood). Why? I ask. Why slice a Ferrari down the middle?

“I didn’t like the way it looked—it was too flat. It just didn’t have that feel.”

If you try to seek out some of Barris’s more creative movie work, you may be mildly disappointed. One of his chopped and channeled Chevy coupes appears in a single scene in 1958’s High School Confidential!, but at least it’s a drag race with a crash. A ’65 Mustang with a Targa roof and a zebra-inspired paint job makes a several-second appearance in Marriage on the Rocks, a Frank Sinatra-Dean Martin domestic comedy (family man Frank switches places with bachelor Dean) that is otherwise forgettable except for an equally brief glimpse of Sinatra dancing in a go-go cage. The his-and-hers Mustangs Barris designed for Sonny and Cher (his was upholstered with bobcat fur and gold mouton carpet, hers with pink patent leather and hot-pink mouton carpet) are seen in even fewer frames of Good Times, the couple’s unsuccessful 1967 attempt (directed by William Friedkin!) at replicating A Hard Day’s Night. Super Van (1978) does not appear to be available on videotape, nor does Mag Wheels, a low-budget 1979 action comedy/ romance about vans and World War III that Barris himself produced and directed and about which he is uncharacteristically unexpansive. Much of his more recent work, on films such as Jurassic Park, has involved rigging cars for stunts or, as on Blade Runner and the Tim Burton Batman movie, helping to engineer and build other peoples designs. Special effects, he says, have cut into the business.

It was on television, especially 60s television with its outlandish premises—suburban monsters, millionaire hillbillies, a mother reincarnated as a 1928 Porter touring car where Barris’s art may have reached its fullest flower. Not only did the nature of the shows call for extravagant cars, the nature of television called for producers to fill up airtime with shots of people driving around. And on no series was this more true than Batman, where the Batmobile, with all its gadgetry, was a character in its own right, arguably more compelling than the leads. It was also a neat example of the customizer’s art. Given a loose concept sketch and only three weeks to produce the first Batmobile, Barris came up with the idea of restyling a 1955 Lincoln Futura “dream car”—a prototype for the car-show circuit that was never manufactured. While keeping the Future's signature bubble roof essentially intact, Barris reworked the rest of the body, pulling out the front end and giving it the sly suggestion of a bat face, extending the fins halfway up the car, scalloping the tail-end lines to suggest bat wings, opening up the wheel wells, investing the car with a sense of wide-bodied power and serrated aggression.

As something to drive, however, the Batmobile was not without its problems. Weighing somewhere between 5,000 and 6,000 pounds, it blew out one of its tires on its very First scene. Indeed, if you look closely during the old episodes you can see that, even though the film has been speeded up, the Batmobile is waddling Henry Hyde-like on its suspension. According to Adam West, it couldn’t do much over 30 and was extremely hard to handle—he spun it out the First time he drove it, showing off to the crew. Stunt drivers complained that the steering would fail.

On the other hand, who cares? What Barris did was take a dopey-looking 50s science-fiction car and turn it into a 60s icon. He made it, in a word, better. Maybe that’s what Barris really is at heart: a brilliant editor. Or, to use a more showbizappropriate metaphor, a genius plastic surgeon. A knife artist.

In 1963, Tom Wolfe fretted that custom culture would eventually fall prey to “the Establishment” and all its “cajolery, thievery and hypnosis.” Of course, this is more or less what has happened. Today, what is known to its marketers as the “specialty automotive equipment” segment of the “automotive aftermarket” is a $6.85 billion industry, most of it in commercially manufactured “custom” accessories you can buy at the Pep Boys. Over the years, too, Detroit has co-opted many of the customizers’ stylistic innovations, incorporating smoother contours, building cars lower to the ground, offering brighter colors.

Tom Wolfe compared Barris to Picasso, then Brancusi, then Benvenuto Cellini.

“In the older days,” Barris says, “they had nothing really nice. Today you can go out and buy a Jaguar XK, you can buy a Lexus, a Viper, a Prowler. They got the new little Mercedes, the Z3 BMWs. You can’t compete, although we do work on them. We change the wheels, we change the color, the sound system, things like that, but we don’t change the style.”

Showbiz culture has changed, too, capitulating to what Wolfe called “the big amoeba god of Anglo-European sophistication that gets you in the East.” Or, if not quite that, at least somewhat more conventional notions of good taste. Stars now want to drive the same Lexuses, Mercedeses, and gargantuan S.U.V.’s— you should see the size of Tori Spelling’s— that the rest of America aspires to. Even the old reliables have toned it down. “Cher’s just paranoid with this drive-by shooting,” Barris explains. “So she tries to be very nondescript. No more of that pearl fuchsia paint and things like that.”

Barris still has a number of celebrity clients, but mostly for promotional cars. There is the Beetle he is doing for the band Hanson, two of whom will be old enough to drive by the time that you are reading this (they have asked him to make the car, Barris says, “more macho”). There is also a half-built convertible for the Spice Girls that has been on hold since Ginger Spice dropped out, bollixing up Barris’s five-seat design. “The only problem is that those girls are crazy,” he grumbles. “They never had so much money in their lives. Now two are pregnant ...” He’s having a hard time getting approvals. It’s the only time I see him cross.

Since Barris is semi-retired, devoting a lot of his time to the car-show circuit, he does much of his work in partnership with a second-generation customizer who has a plant out in Corona, on the edge of the desert, where he makes stretch limos from the obvious Lincolns and Cadillacs, but also from BMWs, Mustangs, Explorers, Porsches—anything to dazzle the prom-night market. It’s hard to say what the difierence is between charming vulgarity and depressing vulgarity, between excess and pornography, but I’d wager it falls somewhere on the continuum between Zsa Zsa Gabor’s gold Rolls and a stretch Hummer with a neon-lit interior and built-in video games. But that’s what an eight-year bull market does to an art form.

If the ultimate point of a custom car is to say to the world, I exist, I’m unique, I’m still here ... damn it!—to borrow from Sandra Bernhard—then Barris has made a thousand self-actualized flowers bloom, maybe more. On the drive back to Los Angeles from Corona, I start to notice how many family cars on the freeway are painted in slightly muted descendants of the Kandy Kolors: Camrys and Saturns and Prizms and sundry minivans in bright metallic reds, greens, blues, and purples—it’s like driving amid a school of tropical Fish. I’m exaggerating a bit for effect and, sure, the cars and colors are stock, stamped out like paper clips or ’NSync CDs. But at least everyone can now have a tiny taste of Cherdom or Gaboritude from back in the day. It’s not a bad legacy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now